Comparative Analysis of Two Community-Based Fishers Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Taal Lake Fishery Resources with Emphasis on the Endemic Freshwater Sardine, Sardinella Tawilis (Herre, 1927)

The Philippine Journal of Fisheries 25Volume (1): 128-135 24 (1-2): _____ January-June 2018 JanuaryDOI 10.31398/tpjf/25.1.2017C0017 - December 2017 Status of Taal Lake Fishery Resources with Emphasis on the Endemic Freshwater Sardine, Sardinella tawilis (Herre, 1927) Maria Theresa M. Mutia1,*, Myla C. Muyot1,, Francisco B. Torres Jr.1, Charice M. Faminialagao1 1National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, 101 Corporate Bldg., Mother Ignacia St., South Triangle, Quezon City ABSTRACT Assessment of fisheries in Taal Lake was conducted from 1996-2000 and 2008-2011 to know the status of the commercially important fishes with emphasis on the endemic freshwater sardine,Sardinella tawilis. Results of the fish landed catch survey in 11 coastal towns of the lake showed a decreasing fish harvest in the open fisheries from 1,420 MT to 460 MT in 1996 to 2011. Inventory of fisherfolk, boat, and gear also decreased to 16%, 7%, and 39%, respectively from 1998 to 2011. The most dominant gear is gill net which is about 53% of the total gear used in the lake with a declining catch per unit effort (CPUE) of 11kg/day to 4 kg/day from 1997 to 2011. Active gear such as motorized push net, ring net, and beach seine also operated in the lake with a CPUE ranging from 48 kg/day to 2,504 kg/day. There were 43 fish species identified in which S. tawilis dominated the catch for the last decade. However, its harvest also declined from 744 to 71 mt in 1996 to 2011. The presence of alien species such as jaguar fish, pangasius, and black-chinned tilapia amplified in 2009. -

Local Convergence and Industry Roadmaps: Potentials and Challenges in the Region

Local Convergence and Industry Roadmaps: Potentials and Challenges in the Region Dir. Luis G. Banua National Economic and Development Authority Region IV-A 1 Outline of Presentation • Calabarzon Regional Economy • Calabazon Regional Development Plan 2011-2016 Regional Economy Population and Land Area Population as of REGION 2000-2010 Calabarzon - largest May 2010 population among regions Philippines 92,335,113 1.90 NCR 11,855,975 1.78 in 2010, surpassing NCR. CAR 1,616,867 1.70 I 4,748,372 1.23 It is second densely II 3,229,163 1.39 populated among regions III 10,137,737 2.14 - 753 people sqm. IV-A 12,609,803 3.07 IV-B 2,744,671 1.79 V 5,420,411 1.46 Land area - 1,622,861 ha. VI 7,102,438 1.35 VII 6,800,180 1.77 VIII 4,101,322 1.28 IX 3,407,353 1.87 X 4,297,323 2.06 XI 4,468,563 1.97 XII 4,109,571 2.46 CARAGA 2,429,224 1.51 ARMM 3,256,140 1.49 The Calabarzon Region’s share to the GDP is 17.2%, which is second highest next to NCR 1.2 Trillion GRDP Growth Rates by Industry GRDP Growth Rates, 2010-2014 Calabarzon Sectoral Shares to GRDP, 2014 (percent) Source: PSA Strong industry/manufacturing/ commercial sector Total No. of Ecozones in Calabarzon, May 31, 2015 Cavite Laguna Batangas Rizal Quezon Total Manufacturing 9 9 14 - - 32 Agro- 1 - - - 1 2 industrial IT Center 1 1 3 2 - 7 IT Park - 4 - - - 4 Medical - - 1 - - 1 Tourism Tourism - - 1 1 - 2 Total 11 14 19 3 1 48 Source: PEZA Export Sales of all PEZA Enterprises vs. -

The Marine Protected Area Network of Batangas Province, Philippines: an Outcome-Based Evaluation of Effectiveness and Performance

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository The Marine Protected Area Network of Batangas Province, Philippines: An Outcome-Based Evaluation of Effectiveness and Performance Dean Rawlins Summary This study looks at the case of four marine protected areas established in two municipalities of Mabini and Tingloy in Batangas Province, Philippines, in order to assess their performance in relation to their initial objectives. It investigates stakeholder perceptions regarding the effectiveness of the MPAs and the current problems facing management of the MPAs. The results highlight issues of equity, lack of community and governmental will and participation, lack of capacity and confidence in management of the local committees and organisations, and difficulties in financing that threaten to jeopardize the protected areas ongoing success. Building governmental support, local capacity building, and a transparent method of financing are seen as key to ensure success in the future. Introduction Over recent years marine protected areas (MPAs) have become a widely-used component of integrated coastal management programmes set up in an attempt to protect, and potentially rehabilitate, coastal ecosystems worldwide. The increasing urgency with which coastal resource management practitioners now view the need to conserve marine resources has led to a surge in the number of MPAs being created and their recognition on an international scale as a viable means to protect resources at the ecosystem level. However, recent experiences in the modern concept of MPA management have brought to light a range of conflicting interests that have impeded the smooth implementation of many projects. -

Region IV CALABARZON

Aurora Primary Dr. Norma Palmero Aurora Memorial Hospital Baler Medical Director Dr. Arceli Bayubay Casiguran District Hospital Bgy. Marikit, Casiguran Medical Director 25 beds Ma. Aurora Community Dr. Luisito Te Hospital Bgy. Ma. Aurora Medical Director 15 beds Batangas Primary Dr. Rosalinda S. Manalo Assumpta Medical Hospital A. Bonifacio St., Taal, Batangas Medical Director 12 beds Apacible St., Brgy. II, Calatagan, Batangas Dr. Merle Alonzo Calatagan Medicare Hospital (043) 411-1331 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Cecilia L.Cayetano Cayetano Medical Clinic Ibaan, 4230 Batangas Medical Director 16 beds Brgy 10, Apacible St., Diane's Maternity And Lying-In Batangas City Ms. Yolanda G. Quiratman Hospital (043) 723-1785 Medical Director 3 beds 7 Galo Reyes St., Lipa City, Mr. Felizardo M. Kison Jr. Dr. Kison's Clinic Batangas Medical Director 10 beds 24 Int. C.M. Recto Avenue, Lipa City, Batangas Mr. Edgardo P. Mendoza Holy Family Medical Clinic (043) 756-2416 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Venus P. de Grano Laurel Municipal Hospital Brgy. Ticub, Laurel, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds Ilustre Ave., Lemery, Batangas Dr. Evelita M. Macababad Little Angels Medical Hospital (043) 411-1282 Medical Director 20 beds Dr. Dennis J. Buenafe Lobo Municipal Hospital Fabrica, Lobo, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds P. Rinoza St., Nasugbu Doctors General Nasugbu, Batangas Ms. Marilous Sara Ilagan Hospital, Inc. (043) 931-1035 Medical Director 15 beds J. Pastor St., Ibaan, Batangas Dr. Ma. Cecille C. Angelia Queen Mary Hospital (043) 311-2082 Medical Director 10 beds Saint Nicholas Doctors Ms. Rosemarie Marcos Hospital Abelo, San Nicholas, Batangas Medical Director 15 beds Dr. -

Tilapia Cage Farming in Lake Taal, Batangas, Philippines

95 CASE STUDY 6: TILAPIA CAGE FARMING IN LAKE TAAL, BATANGAS, PHILIPPINES A. Background 1. Scope and Purpose 1. This case study was undertaken as part of an Asian Development Bank (ADB) special evaluation study on small-scale, freshwater, rural aquaculture development. The study used primary and secondary data and published information to document the human, social, natural, physical, and financial capital available to households involved in the production and consumption of freshwater farmed fish and to identify channels through which the poor can benefit.1 The history and biophysical, socioeconomic, and institutional characteristics of Lake Taal, Batangas, Philippines are described, followed by accounts of the technology and management used for tilapia cage farming and nursery operations, with detailed profiles of fish farmers and other beneficiaries. Transforming processes are discussed with respect to markets, labor, institutions, support services, policy, legal instruments, natural resources and their management, and environmental issues. The main conclusions and implications for poverty reduction are then summarized. 2. Methods and Sources 2. A survey was conducted of 100 tilapia cage farmers and 81 nursery pond farmers from the municipalities of Agoncillo, Laurel, San Nicolas, and Talisay, around Lake Taal, Batangas Province, Philippines. These four municipalities account for at least 98% of the total number of cages in the lake and associated nurseries. The survey was conducted in July–August 2003. Rapid appraisal of tilapia cage farming in Lake Taal, site visits, meetings, and interviews with key informants were undertaken prior to this survey. Survey respondents were identified through stratified random sampling based on the latest official records of each municipality. -

List of Properties for Sale As of February 29, 2020

Consumer Asset Sale Asset Disposition Division Asset Management and Remedial Group List of Properties for Sale as of February 29, 2020 PROP. CLASS / TITLE NOS LOCATION LOT FLOOR INDICATIVE ACCOUNT NOS USED AREA AREA PRICE (PHP) METRO MANILA KALOOKAN CITY 10001000011554 Residential- 001-2014004122 Lot 9 Blk 11 St. Mary St. 174 65 2,501,000.00 House & Lot Altezza Subd. Nova Romania Subd. Brgy Bagumbong, Kalookan City 10001000012916 Residential- 001-2018002058 Blk 2 Lot 44 Everlasting St. 108 53 2,024,000.00 House & Lot Alora Subd. (Nova Romania- Camella) Brgy. Bagumbong, Kalookan City QUEZON CITY 10001000011904 Residential- 004-2015003214 Lot 13-E Blk 1 (interior) Salvia 53 89 1,857,000.00 House & Lot St. brgy Kaligayahan Novaliches, Quezon City MANILA CITY 10001000009823 Residential - 002-2014012057 Unit Ab-1015, 10Th Floor, El n/a 29 1,845,000.00 Condominium Pueblo Manila Condominium, Building Annex B, Anonas Street, Sta. Mesa, Manila 10001000009701 Residential - 002- Unit 820, Illumina Residences n/a 70.5 4,208,000.00 Condominium 2014002439/002 - Illumina Tower, V.Mapa Cor. - P.Sanchez Sts., Sta.Mesa, 2013009279/002 Manila -2013009280 10001000009700 Residential - 002-2014001621 No. 14, Jonathan Street, 114 168 2,950,000.00 House & Lot District Of Tondo, Manila City MARIKINA CITY 10751000000088 Residential- 009-2016004988 Lot 6-B Blk 7 Tanguile St. La 76 100 3,144,000.00 House & Lot Colina Subd. Brgy Fortune Marikina City VALENZUELA CITY 10001000011757 Residential- V-106585 Blk 5 lot 31 Grande Vita 44 46 1,018,000.00 House & Lot Phase 1 (Camella Homes) Brgy. Bignay, Valenzuela City 10001000001753 Residential - V-80135 Lot 28 Block 3, No.2 227 210 2,214,000.00 House & Lot Thanksgiving Cor. -

Enhancing Food Security and Sustainable Livelihoods in Batangas, Philippines, Through Mpas and ICM

ICM Solutions Enhancing Food Security and Sustainable Livelihoods in Batangas, Philippines, through MPAs and ICM The long-term protection and management of coastal and marine resources entails good governance and on- the-ground interventions. In Batangas Province, the implementation of marine protected areas (MPAs) and MPA networks within the framework of an integrated coastal management (ICM) program have provided benefits in food security and sustainable livelihoods, and engaged stakeholders in various sectors and at varying scales to integrate and complement each other’s efforts. Addressing fish stocks goes hand in hand with habitat restoration initiatives in improving food security and reducing ecosystem degradation. Scientific analyses, in parallel with consultations with locals as well as commercial fishers, provide both scientific and practical rationale for management interventions, including seasonal closures for fishing. It is important to educate and build awareness in order to mobilize the community for environmental stewardship and consequently make the community a partner in sustainable coastal development. By facilitating the fishing community themselves to guard and maintain the MPA, the community begins to take ownership and responsibility for local conservation and to protect their livelihoods as fishers. Context “I do not have parcels of land for my children to inherit. I pass on to them the knowledge and lessons that I have learned in a lifetime of fishing … lessons about conserving and protecting the marine and coastal resources. Experience has taught me there is a greater wealth from the sea if its resources are sustainably managed.” These are the heartfelt sentiments of Doroteo Cruzat (Mang Jury), a former fisher who was taught his craft in the waters of Mabini, in the Province of Batangas, Philippines, when he was 10 years old. -

Overlay of Economic Growth, Demographic Trends, and Physical Characteristics

Chapter 3 Overlay of Economic Growth, Demographic Trends, and Physical Characteristics Political Subdivisions CALABARZON is composed of 5 provinces, namely: Batangas, Cavite, Laguna, Quezon and Rizal; 25 congressional districts; 19 cities; 123 municipalities; and 4,011 barangays. The increasing number of cities reflects the rapid urbanization taking place in many parts of the region. The politico- administrative subdivision of CALABARZON per province is presented in Table 3.1. Table 3.1 CALABARZON Politico-Administrative Subdivision, 2015 CONGRESSIONAL PROVINCE CITIES MUNICIPALITIES BARANGAYS DISTRICTS 2010 2015 2010 2015 2010 2015 2010 2015 Batangas 4 6 3 3 31 31 1,078 1,078 Cavite 7 7 4 7 19 16 829 829 Laguna 4 4 4 6 26 24 674 674 Quezon 4 4 2 2 39 39 1,242 1,242 Rizal 4 4 1 1 13 13 188 188 Total 23 25 14 19 128 123 4,011 4,011 Source: DILG IV-A Population and urbanization trends, transportation and settlements The population of CALABARZON in 2015 reached 14.4 million, which is higher than the NCR population by 1.53 million. With an annual growth rate of 2.58 percent between 2010 and 2015, the and NCR. The R , indicating its room for expansion. Urban-rural growth development shows that the Region has increasing urban population compared to rural population. From 1970 to 2010, the region posted increasing urban population with the Province of Rizal having the highest number of urban population among the provinces (Table 3.2). Table 3.2. Percentage Distribution of Urban-Rural Population, CALABARZON, 1970 to 2010 PROVINCE 1970 1980 1990 -

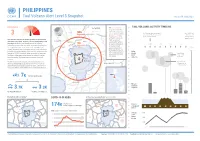

PHILIPPINES Taal Volcano Alert Level 3 Snapshot As of 09 July 2021

PHILIPPINES Taal Volcano Alert Level 3 Snapshot As of 09 July 2021 Maragondon Cabuyao City TAALVictoria VOLCANIC ACTIVITY TIMELINE Alert level Silang LAGUNA With Alert Level 3 on, Indang danger zone in the 7-km City of Calamba Amadeo radius of Taal volcano has Mendez 14km been declared. Should the On 1 July, alert level was raised to 3 As of July 9, Taal danger zone Los Baños after a short-lived phreatomagmatic Volcano is still 3 Bay Alert increase to 4, this plume, 1 km-high occured showing signs of Magallanes will likely be extended to Calauan magmatic unrest Taal Volcano continues to spew high levels of sulfur dioxide 14-km as with 2020 Alfonso Talisay Santo and steam rich plumes, including volcanic earthquakes, in the CAVITE Tagaytay City Tomaseruption, which will drive Nasugbu past days. While alert level 3 remains over the volcano, 7km the number of displaced. 1 JULY 3 JULY 5 JULY 7 JULY volcanologists warn that an eruption is imminent but may not danger zone At the peak of 2020 HEIGHT be as explosive as the 2020 event. Local authorities have City of Tanauan eruption some 290,000 (IN METERS) started identifying more evacuation sites to ensure adherence people were displaced in 3K to health and safety protocols. Plans are also underway for the Laurel 500 evacuation centers or Sulfur transfer of COVID-19 patients under quarantine to temporary Alaminos dioxide Lowest since were staying with friends San Pablo City facilities in other areas, while vaccination sites will also be Malvar (SO2) 1 July at 5.3K Tuy and relatives. -

Invitation to Bid ITB NO

Republic of the Philippines MUNICIPALITY OF BALAYAN Province of Batangas BIDS AND AWARDS COMMITTEE (BAC) 101 Plaza Rizal, Balayan, Batangas Tel. No. (043) 2116-773 Invitation to Bid ITB NO. JRF-2020-020 The Municipal Government of Balayan (MGB), intends to apply the sum of following, to wit: Name of Contract : Construction of Access Road at Government Center (Phase IV) Location : Barangay Caloocan, Balayan, Batangas Approved Budget for The Contract (ABC) : Php 3,989,903.29 Project Duration : 120 cd Source of Fund : 20% DF Bids received in excess of the ABC shall be automatically rejected at bid opening. 1. Completion of the Works is required “see detailed project durations stated above each project”. Bidders should have completed a contract similar to the Project. The description of an eligible bidder is contained in the Bidding Documents, particularly, in Section II. Instruction to Bidders. 2. Bidding will be conducted through open competitive bidding procedures using non- discretionary “pass/fail” criterion as specified in the 2016 Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) of Republic Act 9184 (RA 9184), otherwise known as the “Government Procurement Reform Act.” Bidding is restricted to Filipino citizens/sole proprietorships, cooperatives, and partnerships or organizations with at least seventy five percent (75%) interest or outstanding capital stock belonging to citizens of the Philippines. 4. Interested bidders may obtain further information from MGB Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) Secretariat and inspect the Bidding Documents at the address given below from 9:00am to 4:00pm. 5. A complete set of Bidding Documents may be acquired by interested bidders starting September 7, 2020 (9:00am) from the address below and upon payment of the applicable fee for the Bidding Documents, pursuant to the latest Guidelines issued by the GPPB, in the amount of PhP 5,000.00. -

Batangas, Philippines March, 2005

Summary Field Report: Saving Philippine Reefs Coral Reef Surveys for Conservation In Mabini and Tingloy, Batangas, Philippines March, 2005 A joint project of: Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project with the participation and support of the Expedition volunteers Summary Field Report “Saving Philippine Reefs” Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to Mabini and Tingloy, Batangas, Philippines March 19 – 27, 2005 A Joint Project of: The Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. (Formerly Sulu Fund for Marine Conservation, Inc.) and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project With the participation and support of the Expedition Volunteers Principal investigators and primary researchers: Alan T. White, Ph.D. Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project Tetra Tech EM Inc., Cebu, Philippines Aileen Maypa, M.Sc. Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. Cebu, Philippines Sheryll C. Tesch Brian Stockwell, M.Sc. Anna T. Meneses Evangeline E. White Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. Thomas J. Mueller, Ph.D. Expedition Volunteer Summary Field Report: “Saving Philippine Reefs” Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to Mabini and Tingloy, Batangas, Philippines, March 19–27, 2005. Produced by the Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project Cebu City, Philippines Citation: White, A.T., A. Maypa, S. Tesch, B. Stockwell, A. Meneses, E. White and T.J. Mueller. 2005. Summary Field Report: Coral Reef Monitoring Expedition to Mabini and Tingloy, Batangas, Philippines, March 19– 27, 2005. The Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation, Inc. and the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, Cebu City, 117 p. -

List of Accredited Hospital

LIST OF ACCREDITED HOSPITAL Tel no: (02) 831.6511, (02) 831.6512 LUZON (02) 831.6514 Fax no.: (02) 831.4788 Coordinator: Dr. Araceli Jo NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) MWFSAT 3-5pm TTH 10-12nn rm 301 CALOOCAN CITY MANDALUYONG ACEBEDO GENERAL HOSPITAL DR. VICTOR R. POTENCIANO MEDICAL CENTER 849 General Luis St. Bagbaguin , Caloocan City 163 EDSA, Mandaluyong City Tel no.: (02) 893.5363, (02) 404.4181 Tel no.: (02) 531.4911 – 19, (02) 531.4921 – 24 (02) 400.1272 Fax no.: (02) 531.4659 Fax no.: (02) 983.5363 Coordinator: Dr. Telly S. Cheng Coordinator: Dr. Eddie Acebedo MON-SAT 9-3pm rm 218 PROCEED TO OPD MANILA CITY MANILA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY FILEMON D. TANCHOCO MEDICAL FOUNDATION, INC CHINESE GENERAL HOSPITAL Samson Road , EDSA, Caloocan City 286 Blumentritt St., Sta Cruz, Manila City Tel no.: (02) 367.2031, (02) 366.9589 Tel no.: (02) 711.4141-51, (02) 743.1471 Fax no.: (02) 361.4664 Fax no.: (02) 743.2662 Coordinator: Dr. Ma. Rosario E. Bonagua Coordinator: Dr. Edwin Ong MTW 3:00PM-5:00PM MON-FRI 9-12nn rm 336 PROCEED TO INDUSTRIAL CLINIC DE OCAMPO MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER MARTINEZ MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 2921 Nagtahan St., cor. Magsaysay Blvd, Manila City 198 A. Mabini St., Maypajo, Caloocan City Tel no.: (02) 715.1892, (02) 715.0967 Tel no.: (02) 288.8862 ,(02) 288.8863 Coordinator: Dr. Aloysius Timtiman Fax no.: (02) 288.8861 MTWTHF 9:30-4:30 / S 9:30-1:00pm Coordinator: Dr. Santos del Rio PROCEED TO OPD MON-SAT 9:00am-12:00nn/ PROCEED TO OPD HOSPITAL OF THE INFANT JESUS NODADO GENERAL HOSPITAL - CALOOCAN 1556 Laong-Laan Road,Sampaloc Manila City Area - A Camarin, Caloocan City Tel no.: (02)731.2771, (02) 731.2832 Tel no.: (02) 962.8021 Coordinator: Dr.