Westerly 57-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Wars and White Settlement: the Conflict Over Space in the Australian Commemorative Landscape Matthew Graves, Elizabeth Rechniewski

Black Wars and White Settlement: the Conflict over Space in the Australian Commemorative Landscape Matthew Graves, Elizabeth Rechniewski To cite this version: Matthew Graves, Elizabeth Rechniewski. Black Wars and White Settlement: the Conflict over Space in the Australian Commemorative Landscape. E-rea - Revue électronique d’études sur le monde an- glophone, Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone, 2017, 10.4000/erea.5821. hal-01567433 HAL Id: hal-01567433 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01567433 Submitted on 23 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. E-rea Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone 14.2 | 2017 1. Pastoral Sounds / 2. Histories of Space, Spaces of History Black Wars and White Settlement: the Conflict over Space in the Australian Commemorative Landscape Matthew GRAVES and Elizabeth RECHNIEWSKI Publisher Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone Electronic version URL: http://erea.revues.org/5821 DOI: 10.4000/erea.5821 Brought to you by Aix-Marseille Université ISBN: ISSN 1638-1718 ISSN: 1638-1718 Electronic reference Matthew GRAVES and Elizabeth RECHNIEWSKI, « Black Wars and White Settlement: the Conflict over Space in the Australian Commemorative Landscape », E-rea [Online], 14.2 | 2017, Online since 15 June 2017, connection on 23 July 2017. -

Nyungar Tradition

Nyungar Tradition : glimpses of Aborigines of south-western Australia 1829-1914 by Lois Tilbrook Background notice about the digital version of this publication: Nyungar Tradition was published in 1983 and is no longer in print. In response to many requests, the AIATSIS Library has received permission to digitise and make it available on our website. This book is an invaluable source for the family and social history of the Nyungar people of south western Australia. In recognition of the book's importance, the Library has indexed this book comprehensively in its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI). Nyungar Tradition by Lois Tilbrook is based on the South West Aboriginal Studies project (SWAS) - in which photographs have been assembled, not only from mission and government sources but also, importantly in Part ll, from the families. Though some of these are studio shots, many are amateur snapshots. The main purpose of the project was to link the photographs to the genealogical trees of several families in the area, including but not limited to Hansen, Adams, Garlett, Bennell and McGuire, enhancing their value as visual documents. The AIATSIS Library acknowledges there are varying opinions on the information in this book. An alternative higher resolution electronic version of this book (PDF, 45.5Mb) is available from the following link. Please note the very large file size. http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/e_access/book/m0022954/m0022954_a.pdf Consult the following resources for more information: Search the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI) : ABI contains an extensive index of persons mentioned in Nyungar tradition. -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Colonists and Aborigines in the Early Australian Settlements

Colonists and Aborigines in the Early Australian Settlements WILLIAM DAMPIER, so far as I know the first Englishman to describe the Australian Aborigines, did not take a very favourable view of them. The Inhabitants of this country,' he wrote, 'are the miserablest People in the world. The Hodmadods of Monomatapa, though a nasty People, yet for wealth are Gentlemen to these, who have no Houses and skin Garments, Sheep, Poultry and Fruits of the Earth, Ostrich Eggs, etc. as the Hodmadods have.' Yet he gives a good physical description of them and notes that they 'live in Companies, 20 or 30 men, women and children together'. 'Their only Food,' he adds, 'is a small sort of Fish' — but we must remember that he was speaking of the north-western coast of Australia. There he saw 'neither Herb, Root, Pulse nor any sort of Grain for them to eat... nor any sort of Bird or Beast that they can catch, having no Instruments wherewithal to do so'.1 Further east the Aborigines climbed trees and snared opossums and hunted the kangaroo. Cook had not much intercourse with the Aborigines, but he makes one comment of some interest. 'Their features were far from disagreeable, the voices were soft and tunable and they could easily repeat many words after us, but neither us nor Tupia could understand one word they said.'2 Banks, who saw more of them, devotes some pages of his 'account of that part of New Holland now called New South Wales' to a description of their way of life, artifacts and hunting. -

Greenwood Mark Jandamarra Teachers Notes Final Draft

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers Notes by Dr Robyn Sheahan-Bright Jandamarra by Mark Greenwood and Terry Denton ISBN 9781742375700 Recommended for ages 7-12 yrs Older students and adults will also appreciate this book. These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ........................................... 2 Curriculum areas .................................... 2 Language & Literacy .......................... 2 Visual Literacy .................................. 3 Creative Arts .................................... 4 Studies of Society & Environment ....... 4 SOSE Themes ............................. 4 SOSE Values ............................... 6 Conclusion ............................................. 6 Bibliography of related texts ..................... 7 Internet resources ................................... 8 About the writers .................................... 9 Blackline masters ..............................10-13 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION ‘Burrudi yatharra thirrili ngarra’ We are still here and strong. Jandamarra was an Indigenous hero...whose white ‘bosses’ called him Pigeon. He knew in his heart that the country was inscribed by powerful spirits in the contours of its landscape.The Wandjinas -

Part 6 of Australian Frontier Wars Western Australia

NUNAWADING MILITARY HISTORY GROUP MINI NEWSLETTER No. 30 Part 6 of Australian Frontier Wars Western Australia The first British settlement in Western Australia was established by the British Army, 57th of Foot, (West Middle- sex Regiment) at Albany in 1826. Relations between the garrison and the local Minang people were generally good. Open conflict between Noongar and European settlers broke out in Western Australia in the 1830s as the Swan River Colony expanded from Perth. The Pinjarra Massacre, the best known single event, occurred on 28 October 1833. The Pinjarra massacre, also known as the Battle of Pinjarra, is an attack that occurred in 1834 at Pinjarra, Western Australia on an uncertain number of Binjareb Noongar people by a detachment of 25 soldiers of the 21st of Foot, (North British Fusiliers), police and settlers led by Governor James Stirling. Stirling estimated the Bin- jareb present numbered "about 60 or 70" and John Roe, who also par- ticipated, at about 70–80, which roughly agree with an estimate of 70 by an unidentified eyewitness. On the attacking side, Captain Theophilus Tighe Ellis was killed and Corporal Patrick Heffron was injured. On the defending side an uncer- tain number of Binjareb men, women and children were killed. While Stirling quantified the number of Binjareb killed as probably 15 males, Roe estimated the number killed as 15–20, and an unidentified eyewitness as 25–30 including 1 woman and several children in addi- tion to being "very probable that more men were killed in the river and floated down with the stream". The number of Binjareb injured is un- known, as is the number of deaths resulting from injuries sustained Pinjarra Massacre Site memorial during the attack. -

The Repatriation of Yagan : a Story of Manufacturing Dissent

Law Text Culture Volume 4 Issue 1 In the Wake of Terra Nullius Article 15 1998 The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent H. McGlade Murdoch University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation McGlade, H., The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent, Law Text Culture, 4, 1998, 245-255. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol4/iss1/15 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The repatriation of Yagan : a story of manufacturing dissent Abstract kaya yarn nyungar gnarn wangitch gnarn noort balaj goon kaart malaam moonditj listen Nyungars, I tell you, our people, our brother he come home, we lay his head down ... Old Nyungar men are singing, and the clapping sticks can be heard throughout Perth's international airport late in the night. There are up to three hundred Nyungars who have come to meet the Aboriginal delegation due to arrive on the 11pm flight from London. The delegation are bringing home the head of Yagan, the Nyungar warrior. This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol4/iss1/15 The Repatriation ofYagan: a Story of Manufaduring Dissent Hannah McGlade kaya yarn nyungar gnarn wangitch gnarn noort balaj goon kaart malaam moonditj listen Nyungars, I tell you, our people, our brother he come home, we lay his head down ... Old Nyungar men are singing, and the clapping sticks can be heard throughout Perth's international airport late in the night. -

Protection of Australia's Commemorative Places And

Australian Heritage Council Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments Report prepared for the Minister for the Environment and Energy, the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP Australian Heritage Council March 2018 Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments Report prepared for the Minister for the Environment and Energy, the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons by Attribution 3.0 Australia licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ This report should be attributed as ‘Protection of Australia’s Commemorative Places and Monuments, Commonwealth of Australia 2018’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format: ‘© Copyright, [name of third party]’. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Indigenous Biography and Autobiography

Multiple subjectivities: writing Duall’s life as social biography Kristyn Harman The colonial archive is replete with accounts of the intimacies of life at the frontier in early New South Wales. In reading these records, it is readily apparent that the scribes who mentioned an Indigenous presence had a habit of situating such people at the periphery of colonial society. More often than not, Aboriginal people were cast as supporting actors to the white male leads valorised in accounts of early exploration and settlement. Despite their textual marginalisation, such archival records remain a rich resource for those wanting to appreciate more fully Indigenous contributions to early colonial New South Wales. Reading archival records against the grain has in recent years been embraced as a practice that holds out the potential to resituate indigenes in more active roles, allowing an increasingly complex and nuanced picture of frontier life to emerge. At the same time, this practice raises a methodological issue as to how such lives might best be reinterpreted and represented for a present-day readership. Before discussing how I have dealt with this conundrum in a recently completed research project, let me set the scene with a brief illustrative example. The three anecdotes that follow are sourced from archival records describing a series of events that unfolded in New South Wales between 1814 and 1819. Their inter-relationship will be made evident shortly. In 1814 a party of young men returned to an area to the west of Sydney known as the Cowpastures from an overland journey to a tract of country renamed Argyle by the settlers. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 1

Aboriginal History Volume one 1977 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Editorial Board and Management Committee 1977 Diane Barwick and Robert Reece (Editors) Andrew Markus (Review Editor) Niel Gunson (Chairman) Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer) Peter Corris Luise Hercus Hank Nelson Charles Rowley Ann Curthoys Isabel McBryde Nicolas Peterson Lyndall Ryan National Committee for 1977 Jeremy Beckett Mervyn Hartwig F.D. McCarthy Henry Reynolds Peter Biskup George Harwood John Mulvaney John Summers Greg Dening Ron Lampert Charles Perkins James Urry A.P. Elkin M.E. Lofgren Marie Reay Jo Woolmington Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthro pological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, will be welcomed. Future issues will include recorded oral traditions and biographies, vernacular narratives with translations, pre viously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is respon sible for all unsigned material in the journal. Views and opinions expressed by the authors of signed articles and reviews are not necessarily shared by Board members. The editors invite contributions for consideration; reviews will be commissioned by the review editor. Contributions, correspondence and enquiries concerning price and availa bility should be sent to: The Editors, Aboriginal History Board, c/- Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, GPO Box 4, Canberra, A.C.T. 2600, Australia. Reprinted 1988. ABORIGINAL HISTORY VOLUME ONE 1977 PART 1 CONTENTS ARTICLES W. -

Of Southern Queensland Journals

Aboriginal 'resistance war'tactics-'The Black War'of southern Queensland Journals Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal HOME ABOUT LOGIN REGISTER SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES ANNOUNCEMENTS Aboriginal ‘resistance war’ tactics – ‘The Black War’ of southern Queensland Raymond Constant Kerkhove ABSTRACT Frontier violence is now an accepted chapter of Australian history. Indigenous resistance is central to this story, yet little examined as a military phenomenon (Connor 2004). Indigenous military tactics and objectives are more often assumed than analysed. Building on Laurie’s and Cilento’s contentions (1959) that an alliance of Aboriginal groups staged a ‘Black War’ across southern Queensland between the 1840s and 1860s, the author seeks evidence for a historically definable conflict during this period, complete with a declaration, coordination, leadership, planning and a broader objective: usurping the pastoral industry. As the Australian situation continues to present elements which have proved difficult to reconcile with existing paradigms for military history, this study applies definitions from guerilla and terrorist conflict (e.g. Eckley 2001, Kilcullen 2009) to explain key features of the southern Queensland “Black War.” The author concludes that Indigenous resistance, to judge from southern Queensland, followed its own distinctive pattern. It achieved coordinated response through inter-tribal gatherings and sophisticated signaling. It relied on economic sabotage, targeted payback killings and harassment. It was guided by reticent “loner-leaders.” Contrary to the claims of military historians such as Dennis (1995), the author finds evidence for tactical innovation. He notes a move away from pitched battles to ambush affrays; the development of full-time ‘guerilla bands’; and use of new materials. -

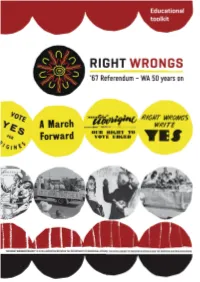

DAA Rightwrongstoolkit.Pdf

CULTURAL DISCLAIMER The Western Australian Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) acknowledges the Traditional Owners and custodians of this land. We pay our respects to Elders past and present, their descendants who are with us today, and those who will follow in their footsteps. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this document contains images and names of deceased persons. Image: Museums Victoria: Item XM 6860. Readers are advised that this toolkit contains terminology and statements that reflect the original authors’ views and those of the period in which they were written, however may not be considered appropriate today. These attitudes do not reflect the views of the DAA, but provide an important historical context. Furthermore, the inclusion of the term ‘Aboriginal’ within this document is used to denote all people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. FOREWORD This year marks the 50-year anniversary of the It is important that all Western Australians historic 1967 Referendum. The Referendum gain a better understanding of our shared was a pivotal point in modern history in history. This Right Wrongs toolkit has been Australia, as more than 90 per cent of developed for this very purpose; to assist Australians voted ‘Yes’ to count Aboriginal educators to foster an increased awareness people in the same census as non-Aboriginal and understanding amongst themselves, their people, and to give the Commonwealth students and the wider community. Government not the States responsibility to make laws for Aboriginal people. This toolkit highlights some of the struggles endured by Aboriginal people in Western Prior to the Referendum, Aboriginal people did Australia, in their attempt to achieve equality.