Lou Howard Tribute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Honours Rcn War Hero

ACTION STATIONS HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 31 ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2013 VICE CHAIR REPORT Captain(N) ret’d Bryan Elson, Vice Chair Canadian Naval Memorial Trust This is my first report Trust. In the coming weeks we expect to receive from since the Board of the contractor the Fundraising Concept document Directors (BOD) which will be a critical tool in moving ahead with the elected me as Vice- BOAP, and will also help to focus our efforts to re- Chair in early invigorate the Trust. September. You will I believe that as trustees we must do understand that in the everything we can to make the organization as circumstances my effective as possible. Among other things that means, message will be brief. as always, that volunteers are needed in a wide As you know, variety of tasks. Please take a good look at your life the office of Chair circumstances to decide whether you can find the time remains vacant, but to play a more active part in what will be an exciting every effort is being made to identify a retired flag time for the Trust and for the BOAP. officer or community leader who would be prepared A path ahead is slowly emerging. We have to take on the role. In the meantime I will do the best I known from the outset of the BOAP that bringing it to can as a substitute, concentrating mainly on the fruition would entail changes in the way the Trust has internal operations of the BOD. Ted Kelly and Cal traditionally functioned. -

Memorial Honours Rcn War Hero

Volume 30 Issue 3 HMCS SACKVILLE Newsletter June–July 2012 WENDALL BROWN HONOURED Len Canfield The 2012 Battle of the Atlantic dinner aboard HMCS SACKVILLE was not only a time to remember and honour all those who served during the longest battle of World War II but also to recognize Commander Wendall Brown who is retiring after nine years as Commanding Officer of SACKVILLE. Vice Admiral (ret’d) Hugh MacNeil, Chair of the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust welcomed guests and trustees, including Rear Admiral David Gardam, Commander Maritime Forces Atlantic and Joint Task Force Atlantic; naval historian Roger Sarty, the guest speaker and Commander (ret’d) Rowland Marshall. Dr. Sarty outlined the significance of the Battle of the Atlantic, its impact on the Atlantic region and the St. Lawrence and Canada’s major contribution to the Allied victory at sea. Cdr Marshall, a retired Saint Mary’s University professor and long-time trustee reflected on his wartime experience as a young sailor. A number of presentations were made to Wendall Brown for his unstinting service to SACKVILLE and the Trust over the years. These included the Maritime Command Commendation which was presented by RAdm Gardam. A number of speakers noted Wendall’s ‘roll up your sleeves’ involvement in all aspects of ship operations, from the bridge to the engine room as well as his ‘good fortune’ on behalf of Canada’s Naval Memorial when making the rounds of Dockyard shops and services. 1 Cdr Brown has turned over command of SACKVILLE to Lieutenant Commander Jim Reddy who has been actively involved with the ship since retiring from the Navy in 2003, including serving as First Lieutenant (XO). -

The Battle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence

Remembrance Series The Battle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence Photographs courtesy of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and the Department of National Defence (DND). © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Minister of Veterans Affairs, 2005. Cat. No. V32-84/2005 ISBN 0-662-69036-2 Printed in Canada The Battle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence Generations of Canadians have served our country and the world during times of war, military conflict and peace. Through their courage and sacrifice, these men and women have helped to ensure that we live in freedom and peace, while also fostering freedom and peace around the world. The Canada Remembers Program promotes a greater understanding of these Canadians’ efforts and honours the sacrifices and achievements of those who have served and those who supported our country on the home front. The program engages Canadians through the following elements: national and international ceremonies and events including Veterans’ Week activities, youth learning opportunities, educational and public information materials (including on-line learning), the maintenance of international and national Government of Canada memorials and cemeteries (including 13 First World War battlefield memorials in France and Belgium), and the provision of funeral and burial services. Canada’s involvement in the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War, and Canada’s efforts during military operations and peace efforts has always been fuelled by a commitment to protect the rights of others and to foster peace and freedom. Many Canadians have died for these beliefs, and many others have dedicated their lives to these pursuits. -

1 ' F ' FAFARD, Charles Omar, Signalman (V-4147)

' F ' FAFARD, Charles Omar, Signalman (V-4147) - Mention in Despatches - RCNVR / HMCS Columbia - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 29 May 1943 and London Gazette of 5 October 1943. Home: Montreal, Quebec HMCS Columbia was a Town Class Destroyer (I49) (ex-USS Haraden) FAFARD. Charles Omar, V-4147, Sigmn, RCNVR, MID~[29.5.43] "This rating showed devotion to duty and was alert, cheerful and resourceful when performing duties in connection with the salvaging of S.S. Matthew Luckenbach. "For good services in connection with the salvage of S.S. Matthew Luckenbach while serving in HMCS Columbia (London Gazette)." * * * * * * 1 FAHRNI, Gordon Paton, Surgeon Lieutenant - Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) - RCNVR / HMS Fitzroy - Awarded as per London Gazette of 30 July 1942 (no Canada Gazette). Home: Winnipeg, Manitoba. Medical Graduate of the University of Manitoba in 1940. He earned his Fellowship (FRCS) in Surgery after the war and was a general surgeon at the Winnipeg General and the Winnipeg Children’s Hospitals. FAHRNI. Gordon Paton, 0-22780, Surg/LCdr(Temp) [7.10.39] RCNVR DSC~[30.7.42] Surg/LCdr [14.1.47] RCN(R) HMCS CHIPPAWA Winnipeg Naval Division, (25.5.48-?) Surg/Cdr [1.1.51] "For great bravery and devotion to duty. For great gallantry, daring and skill in the attack on the German Naval Base at St. Nazaire." HMS Fitzroy (J03 - Hunt Class Minesweeper) was sunk on 27 May 1942 by a mine 40 miles north-east of Great Yarmouth in position 52.39N, 2.46E. It was most likely sunk by a British mine! It had been commissioned on 01 July 1919. -

2018-10-01-39.Pdf

OCTOBER IS • CELEBRATING 75 YEARS PROVIDING RCN NEWS • ON SELECTED TIRES Volume 63 Number 39 | October 1, 2018 UNTIL OCTOBER 27th ASK FOR DETAILS. Canada’s he lthyworkplacemonth VICTORIA (LANGFORD) 2924 Jacklin Road How do you 250.478.2217 fountaintire.com newspaper.comnenewwssppaapeperr..ccoom measure up! We’re MARPAC NEWS CFB ESQUIMALT, VICTORIA, B.C. on this road engage empower evaluate together. LookoutNewspaperNavyNews @Lookout_news LookoutNavyNews See pages 10 and 11 Loving the NAVY! Heather White prepares to fire HMCS Ottawa’s 50-Calibre Heavy Machine Gun while participating in the Canadian Leaders at Sea day sail. Photo by Leading Seaman Shaun Martin, MARPAC Imaging Services Red Barn WITH DND ID, MARKET LIMITED TIME We proudly serve the Your Everyday Specialty Store Esquimalt Enjoy a Location only Canadian Forces Community David Vanderlee, CD, BA FREE COFFEE As a military family we understand Canadian Defence your cleaning needs during ongoing Community Banking Manager with every sandwich, service, deployment and relocation. Mortgage Specialist wrap or salad. www.mollymaid.ca [email protected] M 250.217.5833 OPEN 6AM-9PM MON-FRI, 8AM-9PM SAT-SUN (250) 744-3427 F 250.727.6920 redbarnmarket.ca [email protected] BMO Bank of Montreal, 4470 West Saanich Rd, Victoria, BC 2 • LOOKOUT CELEBRATING 75 YEARS PROVIDING RCN NEWS October 1, 2018 Grey Cup touches down in Esquimalt Peter Mallett contested between four regional sure the sailors of the diving unit Staff Writer Rugby Football Union leagues. It weren’t forgotten when we came, The last time the Grey Cup visited CFB has the names of all 105 cham- and the Cup made it across the One of Canada’s most famous pions engraved on its base, with harbour to Colwood.” Esquimalt it was in celebration of the B.C. -

THE STORY of the U-190 in the Dying Days of the Nazi Regime

THE FINAL MISSION : THE STORY OF THE U-190 In the dying days of the Nazi regime, German U-boats fight to the end. On April 16th, 1945, the U-190 sinks the minesweeper HMCS Esquimalt, the last Canadian warship lost in the Second World War. The survivors endure six hours in the frigid water before being rescued; only twenty-seven of the minesweeper’s seventy-one crewmembers will survive. On May 11, the U-190 receives a transmission from headquarters: each U-boat must surrender to Allied forces. Two Canadian escort vessels are transferred from a convoy with orders to meet and board the U-190. The U-boat is now a prize of war and her crew is made prisoner. During the summer of 1945, the U-190, now property of the Canadian Navy, sets out on an exhibition tour which takes her to the main ports on the St. Lawrence River. The submarine 1 then travels to Trois-Rivières, Quebec City, Gaspé, Pictou, disposal. German submarines (U-boats) were the most effective and Sydney and each time, her presence attracts thousands of deadly arm of the navy. onlookers. Canada’s role in the Battle of the Atlantic was significant. The most important achievement of the Atlantic war was the 25,343 merchant ship voyages made from North American to British ports The Canadian Navy decides to put an end to the U-190’s career under the protection of Canadian forces. on October 21, 1947. The U-boat is towed to the spot where it had sunk the HMCS Esquimalt. -

Celebrating 65 Years As the 17 Wing Community News Source 1952 - 2017

Celebrating 65 years as the 17 Wing Community news source 1952 - 2017 The 5 km Run start for the 9th annual Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Run on Sunday, May 28. The RCAF Run is a charitable fitness event hosted by 17 Wing Winnipeg and held in support of the Soldier On program and the Support Our Troops Fund. Please see page 2 for our articles and pages 8-9 for photos. Photo: Sgt Daren Kraus, 17 Wing Photojournalist the voxair HMCS 17 Wing stand up community love through turns 65 Chippawa Volunteers comedy stands recreation has the ages-a years old welcomes new appreciated at up for 17 wing new outdoor 17 wing love this week commanding celebrations families adventures story officer dinner theatre for you In this issue: Page 2 Page 4 Page 6 Page 10 Page 12 Page 15 2 VOXAIR, 17 Wing Winnipeg, 31 May, 2017 2017 RCAF RUN Feet Take Flight at the 2017 RCAF Run was the first to cross the finish line. Szikora ran the 5km incorporated into Support Our Troops,” said Collins, “so race, and credits his success to hard work and regular it’s still going to the same purposes. The Soldier On Pro- training, as well as determination and a positive men- gram helps ill and injured serving service members and tality. He is an avid runner and cyclist. veterans to return to a new reality of physical fitness, “It’s good to know that at 40 years old I can still keep especially after catastrophic injuries.” up with the young’uns,” said an out of breath Szikora. -

Memorial Honours Rcn War Hero

Volume 30 Issue 5 HMCS SACKVILLE Newsletter Fall 2012 In the last issue of Actions Stations we celebrated Rose Murray’s 100th birthday and as promised, we would now like to introduce you to Trustee and Surgeon Captain ret’d Robert Hand, RNVR/RCN from Sherborn, Massachusetts who has had a long and distinguished career serv- ing two nations and two navies during his first century. Dr. Hand grew up in Sheffield England and studied medi- cine at the University of Glasgow before joining the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in 1934. He had additional training at the Lon- don School of Tropical Medicine which no doubt proved to be very useful later on in his career. When war broke out in 1939, Surgeon Lieutenant Hand was posted to the RN cruiser HMS BERWICK, the flagship of the British North American West Indies Fleet and then to the British Naval Hospital in Bermuda. In 1941 he was appointed Chief Medical Officer in Port of Spain, Trinidad. In the spring of 1948, Dr. Hand emigrated to Canada with his wife and children and transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy in Halifax where he served until 1963. During this time he studied ophthalmology in the United States and upon retirement went into private practice. Dr. Hand remains associated with many profes- sional organizations on both sides of the border and is a member in good standing with the Nova Scotia Naval Officers’ Association. Among the many gestures of good will marking his birth- day was a personal note from Her Majesty the Queen and a Life Membership from the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust Member in honour of his many years as a Trustee. -

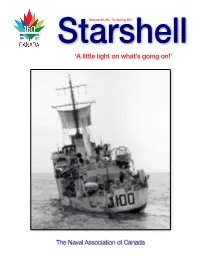

Spring 2017 ‘A Little Light on What’S Going On!’

StarshellVolume VII, No. 78, Spring 2017 ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ The Naval Association of Canada OUR COVER ~ GOOD OL’ NAVY RESOURCEFULNESS! No, this is not intended to show the RCN at its worst but rather at its best, resolving a potentially disastrous situation by exhibiting good old navy inge- nuity! Built for the RN at Vancouver but transferred to the RCN for manning, the Bangor-class minesweeper Lockeport was commissioned on 27 May 1942 and served with Esquimalt Force until 17 March 1943 when she sailed for Halifax. Upon her arrival there on 30 April, she was assigned briefly to WLEF and in June to Halifax Force. In November and December 1943 she was loaned to Newfoundland Force but was withdrawn due to engine trouble. On 9 January 1944, while enroute to Baltimore for refit, her engines broke Starshell down during a storm and she made 190 miles under improvised sail, sewing ISSN-1191-1166 hammocks together and lashing them to the masts as a foresail and mizzen, before being towed the rest of the way to her destination. Upon her return National magazine of the Naval Association of Canada to Halifax in April, Lockeport was ordered to Bermuda to work up, and on Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada the homeward journey she escorted the boats of the 78th Motor Launch Flo- tilla. Returning to Sydney Force in 1944 she was frequently an escort to the www.navalassoc.ca Port-aux-Basques ferry. She left Canada on 27 May 1945 for the UK and was returned to the RN at Sheerness on 2 July to be broken up three years later. -

By Andy Irwin I Was Born in Regina, Saskatchewan on May 28Th, 1925

By Andy Irwin I was born in Regina, Saskatchewan on May 28th, 1925. We lived in Yorkton until 1931, when, after my parents separated, my mother moved my sister and me to New Westminster, BC where we lived with my grandmother. I attended Lord Kelvin Elementary School, and then on to Lord Lister Junior High, which in those days included grades 7, 8 and 9. There were several minor diplomatic crises between Britain and France on one side, and Germany over the latter’s aggressive actions in Europe in 1937-38. Consequently, by 1939 Britain became very concerned and, to get Canada on their side, arranged a Royal Tour for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. New Westminster, known as the Royal City, annually held May Day events. On this particular occasion I was asked to lead a Andy Irwin, 1944 Semaphore Flag presentation in their In the fall of 1941 a Sea Cadet Force was honour. It was an exciting assignment for a being formed and I was one of the first to fourteen year old. leave ‘scouting’ and join Sea Cadets. I really When World War II broke out in enjoyed the training and discipline and in September 1939 I was a newspaper delivery less than a year became a Leading Cadet. I boy for the Vancouver Daily Province. think my Scout training helped. Newspapers were the main source of news In February 1943, at the age of 17, I in those days; television had not yet entered joined the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer our lives. On that fateful Sunday, September Reserve as an Ordinary Seaman. -

AWARDS to the ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY for KOREA

AWARDS to the ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY for KOREA BANFIELD, Nelson Ralph, Lieutenant, CD - Mention in Despatches - RCN / HMCS Sioux - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 27 September 1952. He was made an Acting Warrant (Electrician) on 01 July 1944. He served in HMCS Sioux (DDE – 224) at a Warrant(L) beginning on 01 July 1944. He then served in HMCS Uganda (LCB – 66) beginning on 7 August 1945. He was promoted to Lieutenant(L) on 15 December 1948. He joined HMCS Sioux (DDE – 225) on 02 July 1950 as an electrical officer. After his tour in Korea, he was posted to Naval Headquarters on 17 May 1952. He was then posted to staff of Principal Naval Officer (PNO) west coast in Esquimalt on 27 September 1954. Promoted to Lieutenant-Commander(L) on 10 November 1955. To HMCS Kootenay (DDE – 258) on 30 December 1957. To HMCS Fraser (DDE – 233) on 20 February 1954. To the Staff of Principal Naval Officer Montreal on 2 May 1960. Promoted to Commander on 01 January 1964. To HMCS Niagara / Washington as Naval Member for the Combined Joint Staff on 31 July 1964. BANFIELD. Nelson Ralph, 0-4184, A/Wt(El) [1.7.44] RCN HMCS SIOUX(225) DDE, (?) Wt(L) [1.7.44] HMCS UGANDA(66) LCB, (7.8.45-?) Lt(L) [15.12.48] HMCS SIOUX(225) DDE, (2.7.50-?) CD~[?] NSHQ (17.5.52-?) MID~[27.9.52] St/PNO/West Coast, (27.9.54-?) LCdr(L) [10.11.55] HMCS BYTOWN(D/S) for HMCS KOOTENAY(258) DDE, stand by, (30.12.57-?) HMCS FRASER(233) DDE, (20.2.59-?) (140/60) PNO/Montreal(E57) (2.5.60-?) (430/60) Cdr [1.1.64] NMCJS/Washington/Niagara(E52) (31.7.64-?) “Mentioned for his hard work, cheerfulness, resourcefulness and ingenuity, which combined to keep the electrical equipment in the HMCS Sioux in a high state of efficiency.” * * * * * BONNER, Albert Leo, Chief Petty Officer Second Class (CPO2), BEM, CD - Distinguished Service Medal - RCN / HMCS Nootka - Awarded as per Canada Gazette of 20 December 1952. -

DATE of REPORT Revised June 18, 2015

NAVAL OFFICERS ASSOCIATION OF CANADA L’ASSOCIATION DES OFFICIERS DE LA MARINE DU CANADA BRANCH ANNUAL REPORT April 15 March 16 DATE OF REPORT Revised June 18, 2015 BRANCH NAME NOAC Winnipeg Branch BRANCH PRESIDENT Ron Skelton since 2010 BRANCH NATIONAL DIRECTOR Do not have one TOTAL MEMBERSHIP AT TIME OF LAST 46 AGM CURRENT MEMBERSHIP – REGULAR/LIFE 42 CURRENT MEMBERSHIP – SERVING 0 CURRENT MEMBERSHIP – Nil ASSOCIATES/OTHERS NUMBER OF MEMBERS LOST SINCE LAST 4 Regular AGM NUMBER OF NEW MEMBERS GAINED 0 SINCE LAST AGM CURRENT TOTAL MEMBERSHIP 42 NUMBER OF ORGANIZED EVENTS 14 + 7 (BRANCH MEETINGS, SOCIAL EVENTS) SINCE LAST AGM NUMBER OF COMMEMORATIONS (BOA, 4 REMEMBRANCE DAY, ETC) IN WHICH THE 17 Wing & RMIM Events BRANCH PARTICIPATED SINCE LAST AGM Wardroom/White Ensign 2 schools & graduation NAMES OF MUSEUMS/TRUSTS WITH Naval Museum of Manitoba WHICH THE BRANCH HAS A WORKING Friends of the Museum RELATIONSHIP 17 Wing Mess Shearwater Aviation Museum -1- NAVAL OFFICERS ASSOCIATION OF CANADA L’ASSOCIATION DES OFFICIERS DE LA MARINE DU CANADA BRANCH ANNUAL REPORT April 15 March 16 NAMES OF NAVAL RESERVE DIVISIONS HMCS Chippawa WITH WHICH THE BRANCH HAS A WORKING RELATIONSHIP NAMES OF NAVAL HQs WITH WHICH THE Nil BRANCH HAS A WORKING RELATIONSHIP NAMES OF NAVY LEAGUE, RCNA AND NLCC J. R. K. Millen MERCHANT SERVICE BRANCHES AND White Ensign Club OTHER ORGANIZATIONS WITH WHICH THE BRANCH HAS A WORKING Ex Wren’s Assoc. RELATIONSHIP Ex Chief’s & PO’s Royal Military Institute of Manitoba NAMES OF SEA CADET CORPS WITH RCSCC John Traverse Cornwell