South Africa) from MIS 3 to the Early Holocene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impala to Matubatuba Substation: Vegetation Impact Report

Proposed Lower uMkhomazi Pipeline Project Terrestrial Biodiversity Report Prepared for NM Environmental by GJ McDonald and L Mboyi 07 February 2018 External Review and Amendment J Maivha March 2018 Proposed Lower uMkomazi Pipeline Project Terrestrial Biodiversity Report Executive summary Khuseli Mvelo Consulting was appointed to conduct a terrestrial biodiversity impact assessment as part of the environmental assessment and authorisation process for the proposed Lower uMkhomazi Pipeline Project, within eThekwini Municipality. The proposed development is situated in an area which has either been transformed or impacted upon by commercial and small-scale agricultural activities and alien plant invasion to a greater or lesser extent. Such vegetation as is found is often of a secondary nature where cane fields have been allowed to become fallow and these disturbed and secondary habitats are substantially invaded by forbs and woody species. Near-natural vegetation is limited and may be found along water courses and certain roads. Local sensitivities - vegetation Plants protected provincially The following specially protected species will be affected by the proposed development: Aloe amiculata (Liliaceae/Asphodelaceae) found at and around 30°11'27.09"S/ 30°45'46.30"E, Freesia laxa (Iridaceae) found at WTW1, Kniphofia sp. (Liliaceae/Asphodelaceae) found at both WTW1 and WTW2. These will require a permit from Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife to be translocated. Specially protected species within the general area such as Millettia grandis, Dioscorea cotinifolia (Dioscoreaceae) and Ledebouria ovatifolia (Liliaceae/Hyacinthaceae) will require the developer to apply to the relevant competent authority for permits to move or destroy such species (as appropriate) should they be encountered during construction. -

The Potential of Agroforestry in the Conservation of High Value Indigenous Trees: a Case Study of Umzimvubu District, Eastern Cape

THE POTENTIAL OF AGROFORESTRY IN THE CONSERVATION OF HIGH VALUE INDIGENOUS TREES: A CASE STUDY OF UMZIMVUBU DISTRICT, EASTERN CAPE. SUPERVISOR: PROF. MIKE J. LAWES (FOREST BIODIVERSITY PROGRAMME) MICHAEL O. MUKOLWE MASTERS PROGRAMME IN ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT UNIVERSITY OF NATAL PIETERMARITZBURG JULY 1999 This project was carried out within the Forest Biodiversity Programme School of Botany and Zoology University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg BiODiVERSiTY PROGRAMME UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DEDICATION This work dedicated to Messrs. Toshihiro Shima and Seiichi Mishima, and to my beloved wife Anne Florence Asiko and children Marion Akinyi, Fabian Omondi and Stephen Ochieng "Stevo". 11 ABSTRACT South Africa is not well endowed with indigenous forests which are now known to be degraded and declining at unknown rates. This constitutes a direct threat to quality oflife ofthe resource-poor rural households who directly depend on them and to ecological integrity. It is also recognised that the declining tree resources, particularly the high value indigenous tree species, are increasingly threatened by a number ofgrowing subsistence demands. This emphasised the need to cultivate and conserve high-value tree species such as Englerophytum natalense, Ptaeroxylon obliquum and Millettia grandis on-farm in Umzimvubu District. Agroforestry is recognised as a viable option for optimising land productivity, reducing pressure on the indigenous forests, ensuring a sustainable supply ofdesired tree products and services and improving the quality oflife ofthe resource-poor rural households. This Thesis examines whether agroforestry in Umzimvubu District and similar areas ofSouth Africa has the potential for addressing these needs. It recognises that for successful initiation, implementation and adoption, agroforestry should be considered at two levels, namely, household and institutional. -

Albuca Spiralis

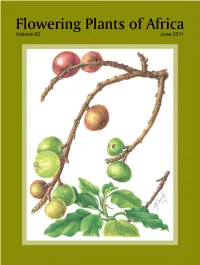

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Nuclear Ribosomal ITS/5.8S Sequences In

Systematic Botany (2002), 27(4): pp. 722±733 q Copyright 2002 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogenetic Analysis of Nuclear Ribosomal ITS/5.8S Sequences in the Tribe Millettieae (Fabaceae): Poecilanthe-Cyclolobium, the core Millettieae, and the Callerya Group JER-MING HU,1,5 MATT LAVIN,2 MARTIN F. W OJCIECHOWSKI,3 and MICHAEL J. SANDERSON4 1Department of Botany, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 59717; 3Department of Plant Biology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287; 4Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616 5Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: Jerrold I. Davis ABSTRACT. The taxonomic composition of three principal and distantly related groups of the former tribe Millettieae, which were ®rst identi®ed from nuclear phytochrome and chloroplast trnK/matK sequences, was more extensively investi- gated with a phylogenetic analysis of nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS/5.8S sequences. The ®rst of these groups includes the neotropical genera Poecilanthe and Cyclolobium, which are resolved as basal lineages in a clade that otherwise includes the neotropical genera Brongniartia and Harpalyce and the Australian Templetonia and Hovea. The second group includes the large millettioid genera, Millettia, Lonchocarpus, Derris,andTephrosia, which are referred to as the ``core Millettieae'' group. Phy- logenetic analysis of nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS/5.8S sequences reveals that Millettia is polyphyletic, and that subclades of the core Millettieae group, such as the New World Lonchocarpus or the pantropical Tephrosia and segregate genera (e.g., Chadsia and Mundulea), each form well supported monophyletic subgroups. -

Thesis Hum 2012 Macabela M V.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Country and City: A study of autobiographical tropes in Ncumisa Vapi’s novel Litshona liphume by Monwabisi Victor MacabelaTown Thesis submitted in fulfilmentCape of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African Languagesof and Literatures at the University of Cape Town University Supervisor: Adjunct Professor T. Dowling Date: 5 June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION: THE TITLE OF THE THESIS ...................................................................... 4 CHAPTER ONE: AIMS AND SIGNIFICANCE OF RESEARCH, LITERATURE REVIEW AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 6 1.2 Statement of the problem ........................................................................ 7 1.3 Aims of the research ................................................................................. 7 1.4 Significance of the study ...........................................................................Town 9 1.5 Literature review .................................................................................... -

Forest Fragmentation South Africa

Content Fragment quality rather than matrix habitat shapes forest regeneration in a South African mosaic-forest landscape Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) dem Fachbereich Biologie der vorgelegt von Diplom-Biologin Alexandra Botzat aus Frankfurt am Main Marburg an der Lahn, April 2012 Content 2 Content Vom Fachbereich Biologie der Philipps-Universität Marburg (Hochschulkennziffer: 1180) als Dissertation am 22.05.2012 angenommen. Dekan: Prof. Dr. Paul Galland Erstgutachterin: Jun.-Prof. Dr. Nina Farwig Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Roland Brandl Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 04.06.2012 Content 4 Content Saskia C. Morgenstern Content 6 Content ‘Humanity has always been, and always will be, a part of nature.’ (Gretchen C. Daily) Content Content 1 General introduction 1 Mosaic-forest landscapes 2 Rodent seed predation in mosaic-forest landscapes 3 Establishment of woody seedlings and saplings in mosaic-forest landscapes 4 Leaf damage of woody seedlings and saplings in mosaic-forest landscapes 6 Aims and outline of the thesis 7 2 Elevated seed predation in small forest fragments embedded in high- contrast matrices 9 Introduction 11 Methods 13 Results 19 Discussion 22 Conclusions 24 Acknowledgements 25 3 Late-successional tree recruits decrease in forest fragments with modified matrix habitat 27 Introduction 29 Methods 31 Results 35 Discussion 42 Conclusions 45 Acknowledgements 46 4 Forest fragment quality rather than matrix habitat shapes herbivory on tree recruits 47 Introduction 49 Methods 51 Results -

Water, Stakeholders and Common Ground

Promotors: Prof. Dr. Linden Vincent, Hoogleraar in de Irrigatie en Waterbouwkunde Prof. Dr. Dorothea Hilhorst, Hoogleraar in de Humanitaire Hulp en Wederopbouw Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof. Dr. C. Leeuwis, Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. K. Rowntree, Rhodes University, South Africa Dr. P. Hebinck, Wageningen Universiteit Dr. J. Woodhill, Wageningen International Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool: CERES Eliab Simpungwe Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 19 december 2006 des namiddags te 13:30 uur in de Aula WATER, STAKEHOLDERS AND COMMON GROUND. Challenges for Multi-Stakeholder Platforms in Water Resource Management South Africa Wageningen University. Wageningen: Eliab Lloyd Simpungwe. 2006. p – 248 ISBN: 90-8504-544-4 Copyright © by 2006, Eliab Lloyd Simpungwe. CONTENTS List of Boxes, Figures, Maps, Plates and Tables iii Abbreviations and Acronyms v Acknowledgements vi Chapter One: Researching MSPs: An Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction and problem context 1 1.2 The rise and rise of MSPs 3 1.3 MSPs as “ participatory ” initiatives 5 1.4 Multi-Stakeholder Platform (MSP) 11 1.5 Selecting the object of study. Why CMFs? 14 1.6 Positioning CMFs 18 1.7 Positioning CMFS within sociotechnical research in local water management 24 1.8 Common ground 26 1.9 Rationale behind this research in MSPs 27 1.10 Research methodology 28 1.11 Thesis structure 32 Chapter Two: Researching -

America, the Beautiful Our New Travel Dreams + Desires Italy, Tasmania

Condé N a s t T r aveler July/August July/August 2 021 · The American Outdoors JULY/AUGUST 2021 · Italy · Tasmania · China · DIVE South Africa · Uruguay INTO · Oregon · Denmark SUMMER · Florida America, the Beautiful · Antarctica Our New Travel Dreams + Desires Italy, Tasmania, China, South Africa, Uruguay, and more cntraveler.com Why wE trAVel › road trip n our claustrophobic lives it’s a rare luxury to experience moments of true escape, when we trade quotidian concerns for unbridled freedom. But a road Itrip along South Africa’s Wild Coast delivers something close to that. Along the way, travelers get a seemingly endless golden expanse at the town of Cintsa. A vast horizon of virgin sands near Port St. Johns: deserted. The ocean view from the Ocean View Hotel in Coffee Bay: all mine. At every stop along this sweep of the Eastern Cape province, known for its scenic hikes and pristine shores, I found myself pondering the same question: This Coast Would having beach after beach to myself ever get old? I had spent four years living in Cape Town but, despite having heard the legends Is Clear of the Wild Coast’s windswept dunes, never made it to this 155-mile stretch on the other side of the country. Though the Eastern Cape is South Africa’s On a visit to her home third-most-populous province, the rugged Wild Coast isn’t as frequently tackled country, Sarah Khan recruits by tourists as well-trammeled circuits like the Western Cape’s Garden Route, KwaZulu Natal’s Midlands Meander, and Mpumalanga’s Panorama Route. -

49 Inspirational Travel Secrets from the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today

2010 49 Inspirational Travel Secrets From the Top Travel Bloggers on the Internet Today www.tripbase.com Front Cover Main Index Foreword Congratulations on downloading your Best Kept Travel Secrets eBook. You're now part of a unique collaborative charity project, the first of its kind to take place on the Internet! The Best Kept Travel Secrets project was initiated with just one blog post back in November 2009. Since then, over 200 of the most talented travel bloggers and writers across the globe have contributed more than 500 inspirational travel secrets. These phenomenal travel gems have now been compiled into a series of travel eBooks. Awe-inspiring places, insider info and expert tips... you'll find 49 amazing travel secrets within this eBook. The best part about this is that you've helped contribute to a great cause. About Tripbase Founded in May 2007, Tripbase pioneered the Internet's first "destination discovery engine". Tripbase saves you from the time-consuming and frustrating online travel search by matching you up with your ideal vacation destination. Tripbase was named Top Travel Website for Destination Ideas by Travel and Leisure magazine in November 2008. www.tripbase.com Copyright / Terms of Use: US eBook - 49 secrets - Release 1.02 (May 24th, 2010) | Use of this ebook subject to these terms and conditions. Tripbase Travel Secrets E-books are free to be shared and distributed according to this creative commons copyright . All text and images within the e-books, however, are subject to the copyright of their respective owners. Best Kept Travel Secrets 2010 Tripbase.com 2 Front Cover Main Index These Secrets Make Dirty Water Clean Right now, almost one billion people in the world don't have access to clean drinking water. -

2015/2016 Annual Report

2015/2016 Annual Report This Annual Report is drafted in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003 (Act 56 of 2003) and the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000). Page 1 of 346 1.1 Mayors Foreword King Sabata Dalindyebo Municipality is one of the fastest growing municipalities in South Africa and the third biggest municipality in the Eastern Cape after the two Metros Nelson Mandela Bay and Buffalo City. As a fastest growing South African municipality, King Sabata Dalindyebo Municipality faces the pressures of a modern, developing towns which are the need to overcome the divisions of the past, and having to deal with a history of inequality and the painful attendant history of separate development. They are the challenges that have resulted from decades of skewed development priorities. And today they are exacerbated by increasing urbanisation, the pressures of broader economic uncertainty and limited resources. With Mthatha town being the former capital city of the erstwhile Transkei government, people from the rural settlement move to Mthatha for better economic opportunities. The consequences of this seemingly unstoppable urbanisation are such that Mthatha is now overcrowded and continues to do so. It is my view as an Executive Mayor of King Sabata Dalindyebo Municipality that, any government must be willing to address those problems that do not appear to have ready solutions, and see them as opportunities. In so doing, the King Sabata Dalindyebo municipality has committed itself to the principles of innovation and dynamic leadership – both of which, we believe, are essential qualities that will help take us forward into the future. -

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119Km (1,324Miles) from Home

Kimberley Crusaders – Part 1 June 7/2018 – 2,119km (1,324miles) from home Hi welcome back everyone… Many of you have confirmed your anticipation in our travel tales ahead. Should there be anyone NOT wishing to receive these, please let us know; we will amend our mailing list, no questions asked! Figuring, we passed our six-month ‘Cape Crusader test run’ run last year, we decided to embark on a twelve-month stint this year. Maybe longer – depends on how we’ll adjust to the nomadic ways of gypsies in the longer term; look/see what life on the road will throw at us So… all a bit open-ended but we’ve done it: Our home is stripped bare and rented. Anyone toying with similar thoughts - One must not underestimate the monumental effort it takes of breaking free from societal life’s seemingly countless entrapments! Whose crazy idea exactly was this in the first place?! Hello golfers, proudly managed a “(w)hole in one”: Squeezing our entire possessions into one room. Credit to Katherine’s most skilful planning and removalists’ even more astonishing stacking skills. This is our vision Empty lounge room camping: Family farewell with sisters Jennifer, Charmaine and Brian FLASHBACK to April 3: In the meantime up north, the wet season has ended, the oppressive humidity disappeared and the welcome heat of the ‘dry’ has arrived beyond the Tropic Of Capricorn: The siren call of tropical Northern Australia beckons yet again. The dry season normally lasts for eight months: No rain, the bluest of blue skies and balmy nights. -

St Michael Goes South

Friday A fine morning, wind light from the SSW, scattered cumulus cloud 5 January over the hills, barometer 30.95 in. The first job was to settle John and Mike back in the Deas Head area and we were off at 0815 with them on board, anchoring in Erebus Cove at 0855 so that they could sort out gear. John and Sam had been waiting for an opportunity to go up a hill and here it was: promising weather, local running only for ‘St Michael’, and they went off up into the Hooker Hills accordingly at 0955. We brought Mike and John off and moved round to Deas Cove, where they went ashore at 1015 while we left a few minutes later for Enderby. There we picked up Milton at 1050 and headed for Ranui Cove, the weather fair, still light but now WSW, and a shower over the hills which made us wonder if Sam and John were going to be disappointed; it soon cleared off again. 1130 at Ranui, where we picked up Brian and left at 1150, anchoring off French’s I. at 1155 for half an hour while we all went ashore and looked it over. Under way again at 1225 and put Milton ashore in his Camp Bay then left again at 1250 heading round to the north of Ewing I. and anchoring at 1305 off its eastern side, in the inlet between the long rock shelves there. After lunch (eaten quickly as there was quite a roll coming in and we did not feel, somehow, like sitting round down below) we all three went ashore, and Nicholas and I looked over some of the places which I had seen on 30 December.