Brain Drain” by Returning to Their Home Countries to Take Advantage of Promising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AU OPTRONICS CORP Form SD Filed 2018-05-31

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM SD Specialized Disclosure Report Filing Date: 2018-05-31 SEC Accession No. 0000950103-18-006801 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER AU OPTRONICS CORP Business Address 1 LI HSIN RD 2 CIK:1172494| IRS No.: 000000000 SCIENC BASED INUSTRIAL Type: SD | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-31335 | Film No.: 18869971 PARK SIC: 3674 Semiconductors & related devices HSIN CHU 300 TAIWAN F5 00000 852-2514-7600 Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM SD Specialized Disclosure Report (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) TAIWAN, REPUBLIC OF CHINA 001-31335 Not Applicable (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer Identification No.) 1 LI-HSIN ROAD 2 HSINCHU SCIENCE PARK HSINCHU, TAIWAN REPUBLIC OF CHINA (Address of principal executive offices) Benjamin Tseng Chief Financial Officer 1 Li-Hsin Road 2 Hsinchu Science Park Hsinchu, Taiwan Republic of China Telephone No.: +886-3-500-8800 Facsimile No.: +886-3-564-3370 Email: [email protected] (Name and telephone, including area code, of the person to contact in connection with this report) Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed, and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) under the Exchange Act for the reporting period from ☒ January 1 to December 31, 2017. Copyright © 2018 www.secdatabase.com. -

Taiwan: Semiconductor Cluster

Taiwan: Semiconductor Cluster Yao Chew Ruijian Li Eric Otoo David Tiomkin Tina Tran Harvard Business School Microeconomics of Competitiveness Course Paper May 2, 2007 Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................. 2 2. Country Analysis ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Position, Brief History and Political Tension with Mainland China..................................... 2 2.2. Taiwan’s Country Balance Sheet in 1950............................................................................ 3 2.3. Economy from 1950 to present ........................................................................................... 4 2.4. Current Economic Position ................................................................................................. 5 2.5. Productivity and Competitiveness ....................................................................................... 7 2.6. Business and Political Environment .................................................................................... 8 2.7. National Diamond............................................................................................................. 10 3. Cluster Analysis..................................................................................................................... 12 3.1 The ITRI and Institutes for Collaboration (IFCs) .............................................................. -

Abstract: the Preparatory Briefing on Taiwan Is the Result of the Collection of Relevant Cluster Information in the Country

Project name Supporting international cluster and business network cooperation through the further development of the European Cluster Collaboration Platform Project acronym ECCP Deliverable title and number D 3.2. – Preparatory Briefing on Taiwan Related work package WP3 Deliverable lead, and partners SPI involved Reviewed by Inno, Commission Contractual delivery date M12 Actual delivery date M15 Start date of project September, 23rd 2015 Duration 4 years Document version V2 Abstract: The preparatory briefing on Taiwan is the result of the collection of relevant cluster information in the country, including business and sector trends, cluster policies and programmes, as well as a cluster mapping. This document is intended to provide an overview of the country’s opportunities for European cluster organisations and SMEs © — 2018 – European Union. All rights reserved The information and views set out in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME) or of the Commission. Neither EASME, nor the Commission can guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither EASME, nor the Commission or any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. D.3.2 - Preparatory Briefing on Taiwan Content 1 Objective of the report .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Taiwan -

Hsinchu Science Park 2006 04 May Hsia

The Development and Outlook of Taiwan’s Science Parks October 2, 2006 Definition of “Science Park” .Near Universities and research centers .Encouraging knowledge-based industries .Helping start-ups 1 Linear Model of Innovation 1. Basic Science Universities 2. Applied Science Research Institutes 3. Technological Development Companies 4. Product Markets Development of Science Parks .1950: Stanford University Science Park .1959: Research Triangle Science Park .1965: Herriot-Watt Univ. Science Park .1970: 22 Science Parks .1970-1980: 39-> Hsinchu Science Park .1980-1990: 270 .1990-2000: 473 2 Taiwan’s Economic Development .1950s –Consumer Goods Industry (Export Zones) .1960s - Rapid Growth of Light Industry (Industrial Parks) .1970s - Capital & Technology Intensive Industries (Research Institutes) .1980s - High-Tech Industries (Sciences Parks) Hsinchu Science Park TaipeiTaipei CKSCKS Internation1 Internation1 Airport Airport HSINCHU SCIENCE PARK TaichungTaichung KaoshiungKaoshiung 3 Hsinchu Science Park HISTORY: Started in 1980 OPERATION: Managed by Park Administration, National Science Council Objectives .Attract Domestic and International High-tech Investors .Facilitate High-tech Development .Recruit High-tech Talents To Enhance HSP Economic Development STSP CTSP 4 Development Model of Hsinchu Science Park 1. Basic Science Universities 2. Applied Science Research Institutes 3. Technological Development Companies 4. Product Markets Incentives and Supports 5 What Science Parks Offer .Easy Access .Academic Environment .Sound Infrastructure -

Chipmos to Present at Investor Conference Hosted by the Taipei Exchange and ICA

Contacts: In Taiwan In the U.S. Jesse Huang David Pasquale ChipMOS TECHNOLOGIES INC. Global IR Partners +886-6-5052388 ext. 7715 +1-914-337-8801 [email protected] [email protected] ChipMOS to Present at Investor Conference Hosted by the Taipei Exchange and ICA Hsinchu, Taiwan - March 31, 2021 - ChipMOS TECHNOLOGIES INC. (“ChipMOS” or the “Company”) (Taiwan Stock Exchange: 8150 and NASDAQ: IMOS), an industry leading provider of outsourced semiconductor assembly and test services (“OSAT”), today announced that it will present virtually at the Taiwan Stock Market Discovery Forum 2021, an investor conference hosted by the Taipei Exchange and ICA on April 8, 2021. Management from the Company, including Jesse Huang, Senior Vice President of Strategy and Investor Relations, will discuss the Company’s recent financial results, business trends and growth opportunities. The Company’s latest investor update is available on the investor relations’ section of its website at www.chipmos.com. About ChipMOS TECHNOLOGIES INC.: ChipMOS TECHNOLOGIES INC. (“ChipMOS” or the “Company”) (Taiwan Stock Exchange: 8150 and NASDAQ: IMOS) (https://www.chipmos.com) is an industry leading provider of outsourced semiconductor assembly and test services. With advanced facilities in Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu Industrial Park and Southern Taiwan Science Park in Taiwan, ChipMOS provide assembly and test services to a broad range of customers, including leading fabless semiconductor companies, integrated device manufacturers and independent semiconductor foundries. Forward-Looking Statements This press release may contain certain forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements may be identified by words such as ‘believes,’ ‘expects,’ ‘anticipates,’ ‘projects,’ ‘intends,’ ‘should,’ ‘seeks,’ ‘estimates,’ ‘future’ or similar expressions or by discussion of, among other things, strategy, goals, plans or intentions. -

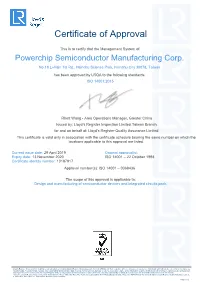

Certificate of Approval

Certificate of Approval This is to certify that the Management System of: Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. No.18 Li-Hsin 1st Rd., Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu City 30078, Taiwan has been approved by LRQA to the following standards: ISO 14001:2015 Rhett Wang - Area Operations Manager, Greater China Issued by: Lloyd's Register Inspection Limited Taiwan Branch for and on behalf of: Lloyd's Register Quality Assurance Limited This certificate is valid only in association with the certificate schedule bearing the same number on which the locations applicable to this approval are listed. Current issue date: 29 April 2019 Original approval(s): Expiry date: 13 November 2020 ISO 14001 – 22 October 1998 Certificate identity number: 10187917 Approval number(s): ISO 14001 – 0068436 The scope of this approval is applicable to: Design and manufacturing of semiconductor devices and integrated circuits pack. Lloyd's Register Group Limited, its affiliates and subsidiaries, including Lloyd's Register Quality Assurance Limited (LRQA), and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as 'Lloyd's Register'. Lloyd's Register assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. Issued by: Lloyd's Register Inspection Limited Taiwan Branch, Room 1008, 10th Floor, No. -

View Complaint

Case 6:20-cv-00444 Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS WACO DIVISION CDN INNOVATIONS, LLC Plaintiff, Civil Action No. 6:20-cv-444 v. MEDIATEK INC., AND MEDIATEK JURY TRIAL DEMANDED USA INC. Defendant. COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff CDN Innovations, LLC (“CDN” or “Plaintiff”), for its Complaint against Defendant MediaTek Inc., (referred to herein as “MediaTek Taiwan”), and Defendant MediaTek USA Inc. (referred to herein as “MediaTek US”) (collectively referred to here as “MediaTek” or “Defendants”), alleges the following: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is an action for patent infringement arising under the Patent Laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. § 1 et seq. THE PARTIES 2. Plaintiff CDN is a limited liability company organized under the laws of the State Georgia with a place of business at 44 Milton A venue, Suite 254, Alpharetta, GA 30009. 3. Upon information and belief, MediaTek Taiwan is a corporation organized under the laws of the Republic of China (Taiwan) with a place of business at No. 1, Dusing 1st Road, Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu, 20078, Taiwan. Upon information and belief, MediaTek Taiwan sells, offers to sell, and/or uses products and services throughout the United States, Page 1 of 14 Case 6:20-cv-00444 Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 2 of 14 including in this judicial district, and introduces infringing products and services into the stream of commerce knowing that they would be sold and/or used in this judicial district and elsewhere in the United States. -

Industrial Research Institutes and Industrial Parks in Taiwan

Legislative Council Secretariat FS17/10-11 FACT SHEET Industrial research institutes and industrial parks in Taiwan 1. Background 1.1 Taiwan has achieved notable economic development over the past half century. Starting out as an agriculture-based economy in the 1950s, Taiwan has transformed itself into a leading producer of high-technology products, with many of its semiconductor, optoelectronic and telecommunications goods commanding a large share of the global market. In 2009, Taiwan ranked first in the world in integrated circuit ("IC") packaging and testing, while placing second in IC design in terms of the global market share. In addition to the IC sector, Taiwan has successfully fostered the development of chemical, metal and machinery industries as its strategic industries. 1.2 Taiwan's economic transformation owes much of its success to, among other things, two major policy initiatives introduced during the 1970s and 1980s respectively. The establishment of the Industrial Technology Research Institute ("ITRI") in 1973, coupled with the opening of the first science-based industrial park in 1980, has helped foster the development of the high-technology industry in Taiwan. Currently, ITRI is the largest government-sponsored industrial research institute in Taiwan, entrusted with the mission of developing new technologies and transferring the results to local industries. 1.3 Against the above background, this fact sheet aims at providing the Panel on Commerce and Industry with the background information on the industrial research institutes in Taiwan, with special reference to the operation of ITRI. The fact sheet also describes the establishment and development of industrial parks in Taiwan. -

Empirical Study of the Affecting Statistical Education on Customer Relationship Management and Customer Value in Hi- Tech Industry

EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education ISSN: 1305-8223 (online) 1305-8215 (print) OPEN ACCESS 2018 14(4):1287-1294 DOI: 10.29333/ejmste/81295 Empirical Study of the Affecting Statistical Education on Customer Relationship Management and Customer Value in Hi- tech Industry Hung-Tai Tsou 1, Yao-Wen Huang 2,3* 1 School of Entrepreneurship, Wenzhou University, CHINA 2 Zhejiang Dongfang Polytechnic, CHINA 3 Department of Business Administration, National Central University, TAIWAN Received 16 August 2017 ▪ Revised 5 December 2017 ▪ Accepted 23 December 2017 ABSTRACT Customer resources is getting important when global economic competitiveness becomes serious as well as foreign advanced technology and talents flow more rapidly and become the development mainstream of Customer Relationship Management. Successful statistics education could integrate customer resources and Customer Relationship Management as well as enhance customer acquisition and create profits for higher return on investment. Besides, providing correct product information for suitable customers at proper time could reinforce customer relationship. Aiming at supervisors and employees in high-tech manufacturers in Hsinchu Science Park, total 500 copies of questionnaire are randomly distributed, and 388 valid copies are retrieved, with the retrieval rate 78%. The research results conclude significant correlations between 1.statistics education and Customer Relationship Management, 2.Customer Relationship Management and customer value, and 3.statistics -

043Determinants Paper Oct. 2019

Taiwan Economic and Political Miracle; Lessons for Oil Exporting Countries in the Middle East 1. Introduction 2. The Role of International Trade 2-1. US – Taiwan Economic Relations 2-2. Japan – Taiwan Trade 2-3. China – Taiwan Economic Relations 3. The Role of State 3-1. Import Substitution (in 1950s) 3-2. Export Promotion (since 1960s) 3-2-1. Export Processing Zones (EPZ) 3-2-2. Shift to Capital-Intensive Industries (since 1970s) 4. The Role of Private Sector 4-1. The Share of ICT1 in Taiwan Economic Success 4-2. Small and Medium Size Enterprises 5. Poverty Combatting Policies in Taiwan 5-1. Land Reform 5-2. Cash Transfer and Health Insurance 5-3. Raising Inequality Since 2000s 6. Political Transformation 7. Lessons from Taiwan’s Success for the Middle East Oil Exporters 8. Concluding Remarks References 1. Introduction Taiwan is a relatively small island with a population of about 23.5 million, yet it plays a leading role in the international high-tech industry. Taiwan that was a backward and poor country in the early 1950s, changed significantly in the past four decades and got the ranking of 22nd country in the world regarding GDP per capita (about USD 25,000 in 2018) richer than the European Union member state Portugal (about USD 23,200 in 2018) with especially a very competitive information technology sector. The economic development of Taiwan was one of the remarkable transformations after the Second 1 Information and Communications Technology 1 World War. Taiwan, like Japan raised from the grossest poverty, and entered into the world international markets for advanced technology products. -

Taiwan: Policy Drive for Innovation

Taiwan: Policy Drive for Innovation Highlights from GRIPS Development Forum Policy Mission Kenichi Ohno (GRIPS) May 2011 Topics The GRIPS Development Forum Team, with Japanese, Ethiopian and Vietnamese members, visited the Republic of China (Taiwan) during March 21-25, 2011. The following issues were studied: Evolution of policy and key industries Policy making process Research institutes Hsinchu Science Park Export processing zones SME Policy Profile of Taiwan Area – 36,191 km 2 Population – 23 million Per capita income – US$19,046 (2010) Industry policy focus (key industry) 1950s – Import substitution (food) 1960s – Export expansion (textile) 1970s – Infrastructure (petrochemical) 1980s – Economic liberalization (IT) 1990s – Industrial upgrading (integrated circuits) 2000s – Global deployment (liquid crystal display) Policy Evolution 1950s to mid 1980s— “Governing the Market” model with strong state and powerful bureaucracy; SMEs as main producers and exporters After mid 1980s—(i) growth of private sector; (ii) rise of large domestic firms, relative decline of SMEs & FDI; (iii) trade liberalization; (iv) economic interaction with Mainland China Current issues: - Innovation, R&D, soft power, national brands - Foster larger firms to compete globally - Cope effectively with Mainland China Silicon Island Taiwan has transformed itself from agro exporter (rice, sugar, bananas) to top ICT manufacturer with global shares as below: MADE IN TAIWAN: MADE BY TAIWAN: Direct export from Taiwan Including overseas production Mask ROM 93.8% Motherboard 95.5% IC foundry 66.4% Notebook PC 95.0% Blank optical disk 63.0% Server 88.9% IC package 44.4% WLAN CPE 81.0% Electronic glass fabric 39.0% Cable Modem 78.6% IC design 27.0% Car navigation device 76.9% DRAM 21.8% LCD monitor 71.8% Note: global market share in 2009 reported by the Ministry of Economic Affairs, ROC. -

Taiwan and Los Angeles County

Taiwan and Los Angeles County Taipei World Trade Center Taiwan and Los Angeles County Prepared by: Ferdinando Guerra, International Economist Principal Researcher and Author Robert A. Kleinhenz, Ph.D., Chief Economist Kimberly Ritter-Martinez, Economist George Entis, Research Analyst February 2015 Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation Kyser Center for Economic Research 444 S. Flower St., 37th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 Tel: (213) 622-4300 or (888) 4-LAEDC-1 Fax: (213)-622-7100 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.laedc.org The LAEDC, the region’s premier business leadership organization, is a private, non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in 1981. GROWING TOGETHER • Taiwan and Los Angeles County As Southern California’s premier economic development organization, the mission of the LAEDC is to attract, retain, and grow businesses and jobs for the regions of Los Angeles County. Since 1996, the LAEDC has helped retain or attract more than 198,000 jobs, providing over $12 billion in direct economic impact from salaries and over $850 million in property and sales tax revenues to the County of Los Angeles. LAEDC is a private, non-profit 501(c)3 organization established in 1981. Regional Leadership The members of the LAEDC are civic leaders and ranking executives of the region’s leading public and private organizations. Through financial support and direct participation in the mission, programs, and public policy initiatives of the LAEDC, the members are committed to playing a decisive role in shaping the region’s economic future. Business Services The LAEDC’s Business Development and Assistance Program provides essential services to L.A.