Battle of Hong Kong Background and Battlefield Tour Points of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette of TUESDAY, the 2Jth of JANUARY, 1948 Published By

tnumb, 3819° 699 SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of TUESDAY, the 2jth of JANUARY, 1948 published by Registered as a newspaper THURSDAY, 29 JANUARY, 1948 The War Office, January, 1948. OPERATIONS IN HONG KONG FROM STH TO 25x11 DECEMBER, 1941 The following Despatch was submitted to the the so-called " Gmdrinkers' Line," with the Secretary of State for War, on 2is£ hope that, given a certain amount of time and November 1945, by MAJOR-GENERAL if the enemy did not launch a major offensive C. M. MALTBY, M.C., late G.O.C., British there, Kowloon, the harbour and the northern Troops in China. portion of the island would not be subjected to artillery fire directed from the land. Time was SIR, also of vital importance to complete demolitions I 'have the honour to address you on the of fuel stores, power houses, docks, wharves, subject of the operations in Hong Kong in etc., on the mainland; to clear certain food Decemiber, 1941, and to forward herewith an stocks and vital necessities from the mainland account of the operations which took place at to the island; to sink shipping and lighters and Hong Kong 'between 8th and 25th December, to clear the harbour of thousands of junks and 1941. sampans. It will be appreciated that to take such irrevocable and expensive steps as men- 2. In normal circumstances this despatch tiori^dln the foregoing sentence was impossible would have been submitted through Head- until it was definitely known that war with quarters, Far East, tout in the circumstances in Japan was inevitable. -

Hong Kong Island - 1 1

832000 834000 836000 838000 Central Park Copyright by Black & Veatch Hong Kong Limited Naval Base Hoi Fu Court Kowloon Map data reproduced with permission Lok Man TO KWA Rock Park Sun Chuen of the Director of Lands(C) Hong Kong Avenue KOWLOON HO MAN TIN WAN Chun Man Ho Man Tin Court Estate Legend Charming Garden To Kwa Wan YAU MA TEI Typhoon Shelter W1 King's Park Oi Man Hill Shafts New Yau Ma Tei Estate Sewage Treatment Works Typhoon Shelter Meteorological Kwun Tong Station Typhoon Shelter King's Park Villa Prosperous Garden KING'S PARK Tunnel Alignment Main Tunnel Alignments Ka Wai Hung Hom KOWLOON BAY Adits Alignments Chuen Estate Laguna Verde HUNG HOM Sorrento Intercepted Catchment Barracks Royal The Peninsula Whampoa Garden Waterfront 67 Subcatchment Boundary Victoria Tower 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 1 1 8 8 TSIM SHA TSUI TAI PAU MAI NORTH POINT North Point V Estate I C SAI YING PUN T O Healthy Village SAI WAN R Tanner Model I Garden Housing A Estate 42 H A R Pacific Palisades B O QUARRY BAY U R BRAEMAR HILL LITTLE GREEN ISLAND SHEK TONG TSUI Braemar Hill Mansions Causeway Bay SHEUNG WAN CENTRAL DISTRICT Typhoon Shelter L The Belcher's NE AN 5 CH 4 6 WAN CHAI 0 va 0 0 R W8 0 0 U 0 6 PH HKU1(P) 46 6 1 L 1 8 SU KENNEDY TOWN Sewage 8 Treatment RR1(P) Barracks Works CAUSEWAY BAY Sai Wan W10 Estate 3 MID-LEVELS vc Kung Man W11(P) 45 Tsuen Kwun Lung LUNG FU SHAN P5(P) 137 Lau 13 C 0 C 0 PFLR1(P) H Lai Tak 0 H 12 W5(P) A + TAI HANG A 0 Tsuen 7 Added Tunnel 8 + A W12(P) B 10/2005 LWG + C 5 H Scheme 0 H 0 00 0 0 240 A +0 C 8 0 VICTORIA P 7EAK + A EASTERN -

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

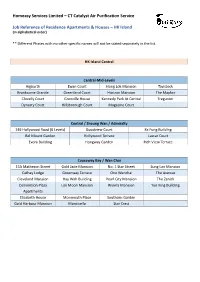

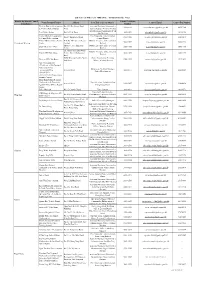

CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence

Homeasy Services Limited – CT Catalyst Air Purification Service Job Reference of Residence Apartments & Houses – HK Island (in alphabetical order) ** Different Phases with no other specific names will not be stated separately in the list. HK Island Central Central-Mid-Levels Aigburth Ewan Court Hong Lok Mansion Tavistock Branksome Grande Greenland Court Horizon Mansion The Mayfair Clovelly Court Grenville House Kennedy Park At Central Tregunter Dynasty Court Hillsborough Court Magazine Court Central / Sheung Wan / Admiralty 149 Hollywood Road (6 Levels) Goodview Court Ka Fung Building Bel Mount Garden Hollywood Terrace Lascar Court Evora Building Hongway Garden Rich View Terrace Causeway Bay / Wan Chai 15A Matheson Street Gold Jade Mansion No. 1 Star Street Sung Lan Mansion Cathay Lodge Greenway Terrave One Wanchai The Avenue Cleveland Mansion Hay Wah Building Pearl City Mansion The Zenith Convention Plaza Lok Moon Mansion Riviera Mansion Yue King Building Apartments Elizabeth House Monmouth Place Southorn Garden Gold Harbour Mansion Monticello Star Crest Happy Valley / East-Mid-Levels / Tai Hang 99 Wong Nai Chung Rd High Cliff Serenade Village Garden Beverly Hill Illumination Terrace Tai Hang Terrace Village Terrace Cavendish Heights Jardine's Lookout The Broadville Wah Fung Mansion Garden Mansion Celeste Court Malibu Garden The Legend Winfield Building Dragon Centre Nicholson Tower The Leighton Hill Wing On Lodge Flora Garden Richery Palace The Signature Wun Sha Tower Greenville Gardens Ronsdale Garden Tung Shan Terrace Hang Fung Building -

(Anisoptera: Gomphidae) Hong Kong

Odonatologica24(3): 319-340 SeptemberI, 1995 The gomphiddragonflies of HongKong, with descriptions of two new species (Anisoptera: Gomphidae) K.D.F. Wilson 6F, 25 Borret Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong Received September 30, 1993 / Revised and Accepted March 3, 1995 16 9 of these have been recorded from spp. are enumerated, not previously Hong S and Lamello- Kong. Melligomphusmoluani sp.n. (holotype : Mt Butler, 8-VII-1993) Tai collected larva gomphus hongkongensis sp.n. (holotype <J; Tong, as 22-V-1993, emerged 6-VI-1993) are described and illustrated. - The female ofGomphidiakelloggi Needham and Leplogomphus elegans hongkong-ensis Asahina are described for the first time. The hitherto unknown larva of Stylo-gomphus chunliuae Chao, Megalogomphussommeri Sel, and Gomphidiakelloggi Needham are illustrated. The of in a new record presence Paragomphus capricornis (Forster) Hong Kong represents for Chinese Territory. INTRODUCTION The odonatefaunaofHong Kong has been documentedby ASAHINA (1965,1987, 1988),LAI(1971), MATSUKI(1989,1990),MATSUKI et al. (1990), HAMALAINEN Lai’s (1991) andWILSON (1993). papercontains some interesting records including Ictinogomphus rapax (Ramb.), but a number of misidentificationsare apparent. ASAHINA (1987) chose to leave the paper by Lai uncited in his revised list of the OdonataofHong Kong, butthe ofIctinogomphus recorded here as I. pertinax presence , (Hagen), is here confirmed. ASAHINA (1988) described Leptogomphus elegans hongkongensis from Hong Kong and ASAHINA (1965, 1988) recorded further four species of Gomphinae; Heliogomphus scorpio (Ris), Asiagomphus hainanensis(Chao), A. septimus (Needham) and Ophiogomphus sinicus (Chao). MATSUKI (1989) de- scribed the larvae ofa species of Onychogomphus and MATSUKI et al. (1990) re- corded Stylogomphus chunliuae Chao.Further material, including malesand females of this Onychogomphus sp., has been obtained and the species is described here as Melligomphus moluami sp.n. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Pte. John Macpherson

'C' FORCE PERSONNEL SUMMARY Battle of Hong Kong and Japanese Prisoners of War, 1941 to 1945 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Regiment 1st Bn The Winnipeg Grenadiers Regt No Rank Last Name First Name Second Names H20820 Private MACPHERSON John C. Appointment Company Platoon HQ Coy Original Town from Enlistment Region Decorations Roseisle MB Manitoba Previous Unit Date of transfer The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada 41 Oct 09 Previous tours Dates of tour 2. TRANSPORTATION - HOME BASE TO VANCOUVER Mode of Travel: CPR Troop Train Stations: Winnipeg, MB; 41 Oct 25, 0900 hrs Banff, AB; 41 Oct 26, 1500hrs; route march Vancouver, BC; 41 Oct 27, 0330 hrs; arrived Vancouver, BC, Oct 27, 0900 hrs; pulled away from wharf 3. TRANSPORTATION - VANCOUVER TO HONG KONG Troop Ship: HM Transport Awatea Vancouver, BC: 41 Oct 27, 2130 hr Honolula, Hawaii: 41 Nov 02, 0900 hrs 41 Nov 02, 1730 hrs Manila, Phillipines: 41 Nov 14, 0930 hrs 41 Nov 14, 1630 hrs Kowloon, Hong Kong: Holt's Wharf, Kowloon, 41 Nov 16, 0930 hrs 4. CAMPS BEFORE THE BATTLE Name of Barracks Camp Location Dates Hankow Barracks Sham Shui Po Camp Kowloon 1A. FIELD PROMOTIONS Rank Appointment (Rank and appointment held when left Canada) Private Promotion 1 Date Appointment Comments Promotion Date Appointment Comments Promotion Date Appointment Comments 5. BATTLE INFORMATION Date of Capture 41/12/25 Dates of Action 41 Dec 06 Name of location Hankow Barracks, Shamshuipo Military Camp Comments In the evening, China Command orders a general mobilization and all units to man battle positions Dates -

Leases Granted at Nominal Or Nil Land Premium for Recreational Purposes Serial No. Name of Holder Location and Lot No. Land Prem

Annex Leases Granted at Nominal or Nil Land Premium for Recreational Purposes Land Serial Name of Holder Location and Lot No. Government Rent No. Premium 1. The Scout Association of Hong IL 8961 Mansion Street, North Point NIL Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value Kong 2. The Royal Hong Kong Yacht ML 709, Kellett Island NIL $1,000 per annum Club 3. The Royal Hong Kong Yacht RBL 1181, Middle Island $1,000 Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value Club 4. Aberdeen Boat Club Limited AIL 454 Shum Wan Road, Brick Hill $1,000 Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value 5. The Hong Kong Golf Club RBL 1117 Deep Water Bay NIL Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value 6. The Hong Kong Country Club RBL 1129 Wong Chuk Hang Road NIL Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value 7. The Hong Kong Cricket Club IL 9019 No. 137 Wong Nai Chung Gap $1,000 Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value Road 8. Hong Kong Football Club IL 8846 Sports Road, Happy Valley $1,000 Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value 9. South China Athletic IL 8850 Caroline Hill Road, So Kon Po NIL Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value Association 10. Chinese Recreation Club, Hong IL 8875 Tung Lo Wan Road NIL Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value Kong 11. Craigengower Cricket Club IL 8881 No. 188 Wong Nai Chung Road $1,000 Annual Rent at 3% of Rateable Value - 2 - Land Serial Name of Holder Location and Lot No. Government Rent No. -

227724/L/2400 Visual Envelope

SHEK LEI PUI Lai Yiu Wonderland L 30 495 Estate Villas RESERVOIR E 0 · Man Wo D N 542 Yuen Ling Y Heung A N ÁA± E E E O U E E E E L E «n s L R ·O¶ Lookout L DO NOT SCALE DRAWING. CHECK ALL DIMENSIONS ON SITE. T ¤ ‚ß A Chung 0 E ¯ 0 ¤ 2 V Nam Wai l 400 N ® 2 O •⁄ Kau Tsin T N 0 ªø§ 0 P y 0 0 TSZ WAN SHAN 0 0 Ä «nà 0 0 t⁄ G ¤ H S U ªF ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ⁄Es– ¤ N 0 S E U 0 Cheung Hang Village 0 ¦ 0 Ser0 Res T 0 0 ¤û Uk 0 A N H Nam Pin KOWLOON I LION ROCK TUNG SHAN W C LEGEND A t⁄ 0 0 0 0 ·O· 0 0 Ngau Liu C «@ Wai 0 c OVE ARUP & PARTNERS HONG KONG LIMITED. E T RECEPTION ¦ Y ¦ Ser Res L N O 2 s B R 4 'S 6 8 ·O¥ 0 2 H Pei Tau 4 I I R ” RESERVOIR §‹ F E O 0 j I O 0 ¤ 411 è 3 ¸3 L 3 N 3 3 4 E 4 4 V A G C Wo Mei N R BEACON HILL ã I E Tsz Oi ¤ C ¤j A ¤ « ›8 O 8 8 8 ¨F¥Ð 8 8 8 ¯E´ E ¤ E ¤ O S R ¤ ªE¥ C Âo¤ L 457 Shatin Pass Court Tai Lam E N Wah Yuen ÁA± O ½ W ¤û Highland ¤ R ® C G S CHAM TIN SHAN Estate ' Water Treatment O Lookout K Wu ¥Ø s Chuen K O E Ngau Pui Park ¥– Works ¤ 200 t⁄ T ·O¼ Tsz Ching Estate Shek Pok 100 HEBE KNOLL PROPOSED STUDY AREA T A Wo ¤U¸ C Shek Lei Tau U Ser Res t⁄ 300 T Wai A N ·O¦ S Ser Res N ·O¥ S 122 † E HA KWAI CHUNG T Tsz Lok Tsz On ¼X H 436 L t⁄ Tsz Man Estate E A L ¹v Mok Tse Che Estate N N E Ser Res Court t⁄ Cemetery I Firing C ¯ª³ EPA t⁄ «n¤ L K ·O± Ser Res N R H O Ser Res Range 305 I A Tsz Hong Estate Nam Shan Mei I 2 ¦y R y•qˆ \ 585 R 00 D 0 ¦Ë 0 0 0 A Lai King 1 3 O ¥´¹ PIPER'S EAGLE'S NEST 0 Cho Yiu »A¦Ë A M Chuk Kok 0 D ' S S Correctional HILL ( TSIM SHAN ) 2 T' SECONDARY ZONE OF VISUAL ENVELOPE Chuen -

District : Kowloon City

District : Wan Chai Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,194) B01 Hennessy 13,277 -22.78% N Expo Drive East, District Boundary 1. CAUSEWAY CENTRE 2. KIN LEE BUILDING NE Tonnochy Road E Gloucester Road, Stewart Road SE Johnston Road, Stewart Road, Thomson Road S Bullock Lane, Cross Street, Kennedy Road Queen's Road East, Thomson Road Wan Chai Road SW Cross Street, Johnston Road, O'brien Road Spring Garden Lane W Fleming Road, O'brien Road NW Fleming Road, Gloucester Road B1 District : Wan Chai Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,194) B02 Oi Kwan 13,340 -22.41% N Marsh Road 1. MAN ON HOUSE NE Marsh Road E Marsh Road SE Marsh Road, Morrison Hill Road Tin Lok Lane S Hau Tak Lane, Morrison Hill Road Queen's Road East, Stubbs Road Wong Nai Chung Road SW Bullock Lane, Fleming Road, Johnston Road Queen's Road East, Stewart Road Thomson Road W Gloucester Road, Stewart Road NW Gloucester Road, Hung Hing Road Tonnochy Road, District Boundary B2 District : Wan Chai Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,194) B03 Canal Road 13,525 -21.34% N District Boundary 1. ELIZABETH HOUSE 2. LOCKHART HOUSE NE District Boundary E District Boundary SE Hoi Ping Road, Hysan Avenue Lee Garden Road, Leighton Road Percival Street, Russell Street S Hennessy Road, Leighton Road, Marsh Road Morrison Hill Road, Tin Lok Lane SW Marsh Road W NW District Boundary B3 District : Wan Chai Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,194) B04 Causeway Bay 13,549 -21.20% N Victoria Park Road, District Boundary 1. -

41912405 Masters Thesis CHEUNG Siu

University of Queensland School of Languages & Comparative Cultural Studies Master of Arts in Chinese Translation and Interpreting CHIN7180 - Thesis Translation of Short Texts: A case study of street names in Hong Kong Student: Shirmaine Cheung Supervisor: Professor Nanette Gottlieb June 2010 ©2010 The Author Not to be reproduced in any way except for the purposes of research or study as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 Abstract The topic of this research paper is “Translation of Short Texts: A case study of street names in Hong Kong”. It has been observed that existing translation studies literature appears to cater mainly for long texts. This suggests that there may be a literature gap with regard to short text translation. Investigating how short texts are translated would reveal whether mainstream translation theories and strategies are also applicable to such texts. Therefore, the objectives of the paper are two-fold. Firstly, it seeks to confirm whether there is in fact a gap in the existing literature on short texts by reviewing corpuses of leading works in translation studies. Secondly, it investigates how short texts have been translated by examining the translation theories and strategies used. This is done by way of a case study on street names in Hong Kong. The case study also seeks to remedy the possible paucity of translation literature on short texts by building an objective and representative database to function as an effective platform for examining how street names have been translated. Data, including street names in English and Chinese, are collected by way of systematic sampling from the entire data population. -

Report on the Management of Recreation and Sports Facilities

For information WCDC DWFMC Paper No.2/2021 9 February 2021 Report on the Management of Recreation and Sports Facilities and Progress of Works in the Wan Chai District by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department between September and December 2020 Purpose This paper reports to Members on the management of recreation and sports facilities by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) in the Wan Chai District. Impact of the Epidemic on Recreation and Sports Facilities managed by LCSD 2. In light of the latest situation of COVID-19, LCSD has temporarily closed some of its leisure venues/facilities until further notice from 10 December 2020, including public swimming pools, sports centres, hard-surfaced soccer pitches, grass soccer pitches, cricket grounds, basketball courts, volleyball courts, handball courts, tennis courts, sports grounds, outdoor fitness equipment, children's play equipment, etc. LCSD will continue to closely monitor the latest epidemic situation and review the above-mentioned arrangements in due course. The updated arrangements on venue facilities and the services that have been affected will be disseminated to the public through webpage and press release. Management of Facilities 3. To enable the District Council to have a better understanding of the services provided by LCSD, papers are submitted on a regular basis to report to Members on the utilisation and management of the recreation and sports facilities in the district as well as the service levels and performance of LCSD’s outsourced services contractors. 4. The utilisation of the recreation and sports facilities in the district between September and December 2020 is set out in Annex I.