Submission to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Electoral Reforms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(01 JULAI 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. Kes Baharu COVID-19

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 182/2021 JAWATANKUASA PENGURUSAN BENCANA NEGERI SARAWAK KENYATAAN MEDIA (01 JULAI 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. Kes Baharu COVID-19. Hari ini terdapat 544 kes baharu COVID-19 dikesan. Sejumlah 338 atau 62.13 peratus daripada jumlah kes ini telah dikesan di lima (5) buah daerah iaitu di Daerah Kuching, Tebedu, Sibu, Bintulu dan Miri. Daerah-daerah yang merekodkan kes pada hari ini ialah daerah Kuching (118), Tebedu (63), Sibu (58), Bintulu (56), Miri (43), Song (41), Telang Usan (21), Serian (17), Bau (15), Kanowit (15), Samarahan (15), Marudi (11), Kapit (11), Subis (10), Sri Aman (7), Tatau (6), Tanjung Manis (6), Mukah (5), Asajaya (4), Simunjan (3), Meradong (3), Saratok (3), Lundu (2), Sarikei (2), Bukit Mabong (2), Sebauh (2), Belaga (1), Matu (1), Lawas (1), Julau (1) dan Betong (1). Ini menjadikan jumlah keseluruhan kes meningkat kepada 65,395. 1 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 182/2021 Daripada 544 kes baharu yang dilaporkan, seramai 74 orang telah menunjukkan tanda dan mengalami gejala jangkitan COVID-19 semasa saringan dijalankan. Manakala, seramai 464 orang kes atau yang dikesan adalah terdiri daripada individu yang telah diberikan arahan perintah kuarantin. Secara ringkas kes-kes ini terdiri daripada: • 334 kes merupakan saringan individu yang mempunyai kontak kepada kes positif COVID-19 (43 kes bergejala); • 125 kes merupakan saringan individu dalam kluster aktif sedia ada (kes tidak bergejala); • 52 kes merupakan lain-lain saringan di fasiliti kesihatan (3 kes bergejala); • 28 kes merupakan saringan individu bergejala di fasiliti kesihatan; • 3 kes melibatkan individu yang balik dari negeri-negeri lain di dalam Malaysia (Import B) (kes tidak bergejala); • 2 kes melibatkan individu yang balik dari luar negara (Import A) iaitu dari Indonesia (kes tidak bergejala). -

SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority

For Reference Only T H E SARAWAK GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PART II Published by Authority Vol. LXXI 25th July, 2016 No. 50 Swk. L. N. 204 THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDINANCE THE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS ORDER, 2016 (Made under section 3) In exercise of the powers conferred upon the Majlis Mesyuarat Kerajaan Negeri by section 3 of the Administrative Areas Ordinance [Cap. 34], the following Order has been made: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Administrative Areas Order, 2016, and shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of August, 2015. Administrative Areas 2. Sarawak is divided into the divisions, districts and sub-districts specified and described in the Schedule. Revocation 3. The Administrative Areas Order, 2015 [Swk. L.N. 366/2015] is hereby revokedSarawak. Lawnet For Reference Only 26 SCHEDULE ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS KUCHING DIVISION (1) Kuching Division Area (Area=4,195 km² approximately) Commencing from a point on the coast approximately midway between Sungai Tambir Hulu and Sungai Tambir Haji Untong; thence bearing approximately 260º 00′ distance approximately 5.45 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.1 kilometres to the junction of Sungai Tanju and Loba Tanju; thence in southeasterly direction along Loba Tanju to its estuary with Batang Samarahan; thence upstream along mid Batang Samarahan for a distance approximately 5.0 kilometres; thence bearing approximately 180º 00′ distance approximately 1.8 kilometres to the midstream of Loba Batu Belat; thence in westerly direction along midstream of Loba Batu Belat to the mouth of Loba Gong; thence in southwesterly direction along the midstream of Loba Gong to a point on its confluence with Sungai Bayor; thence along the midstream of Sungai Bayor going downstream to a point at its confluence with Sungai Kuap; thence upstream along mid Sungai Kuap to a point at its confluence with Sungai Semengoh; thence upstream following the mid Sungai Semengoh to a point at the midstream of Sungai Semengoh and between the middle of survey peg nos. -

Voting Strategy of the Iban in Sarawak, Malaysia

Southeast Asian SStudiesODA R.:, Vol. Development 40, No. 4, Policy March and 2003 Human Mobility in a Developing Country Development Policy and Human Mobility in a Developing Country: Voting Strategy of the Iban in Sarawak, Malaysia SODA Ryoji* Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine the interaction between the development policy of the Sarawak government and the indigenous people in rural areas, by observing the mobility of rural- urban migrants. Over the last decade or so, the Sarawak government has been promoting vari- ous kinds of development schemes in rural areas, and the indigenous people, who are politically and economically marginalized, seem to act in compliance with the government policy for the purpose of securing development funds. Some scholars have criticized this kind of passive com- pliance as a “subsidy syndrome.” However, closer observation of the voting behavior of the indigenous people reveals that they strive to maximize their own interests, albeit within a limited range of choices. What is noteworthy is the important role played by rural-urban migrants in rural development. They frequently move back and forth between urban and rural areas, are leaders in the formation of opinion among rural residents, and help obtain development resources for their home villages. Examining the mobility of urban migrants during election periods is useful for reconsidering the dichotomy between development politics and the vulnerable agricul- tural community, and also urban-rural relations. Keywords: Iban, Sarawak, voting activity, rural-urban migration, development policy, rural devel- opment I Introduction Based on my previous studies of rural-urban population mobility of the Iban, an indigenous people in Sarawak [Soda 1999a; 2000], it is apparent that rural-urban relations — more specifically, the mobility of indigenous peoples between rural and urban areas — is significantly affected by development-biased political system. -

Belum Disunting Unedited

BELUM DISUNTING UNEDITED S A R A W A K PENYATA RASMI PERSIDANGAN DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI OFFICIAL REPORTS MESYUARAT KEDUA BAGI PENGGAL KETIGA Second Meeting of the Third Session 5 hingga 14 November 2018 DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI SARAWAK KELAPAN BELAS EIGHTEENTH SARAWAK STATE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY RABU 14 NOVEMBER 2018 (6 RABIULAWAL 1440H) KUCHING Peringatan untuk Ahli Dewan: Pembetulan yang dicadangkan oleh Ahli Dewan hendaklah disampaikan secara bertulis kepada Setiausaha Dewan Undangan Negeri Sarawak tidak lewat daripada 18 Disember 2018 KANDUNGAN PEMASYHURAN DARIPADA TUAN SPEAKER 1 SAMBUNGAN PERBAHASAN ATAS BACAAN KALI YANG KEDUA RANG UNDANG-UNDANG PERBEKALAN (2019), 2018 DAN USUL UNTUK MERUJUK RESOLUSI ANGGARAN PEMBANGUNAN BAGI PERBELANJAAN TAHUN 2019 (Penggulungan oleh Para Menteri) Timbalan Ketua Menteri, Menteri Permodenan Pertanian, Tanah Adat dan Pembangunan Wilayah [YB Datuk Amar Douglas Uggah Embas]………..……………………… 1 PENERANGAN DARIPADA MENTERI (1) Menteri Kewangan II [YB Dato Sri Wong Sun Koh]………..…………………………………… 25 (2) YB Puan Violet Yong Wui Wui [N.10 – Pending]………..………………………………..………………… 28 SAMBUNGAN PERBAHASAN ATAS BACAAN KALI YANG KEDUA RANG UNDANG-UNDANG PERBEKALAN (2019), 2018 DAN USUL UNTUK MERUJUK RESOLUSI ANGGARAN PEMBANGUNAN BAGI PERBELANJAAN TAHUN 2019 ( Sambungan Penggulungan oleh Para Menteri) Ketua Menteri, Menteri Kewangan dan Perancangan Ekonomi [YAB Datuk Patinggi (Dr) Abang Haji Abdul Rahman Zohari Bin Tun Datuk Abang Haji Openg]…………………………………………… 35 RANG UNDANG-UNDANG KERAJAAN- BACAAN KALI KETIGA -

Klinik Perubatan Swasta Sarawak Sehingga Disember 2020

Klinik Perubatan Swasta Sarawak Sehingga Disember 2020 NAMA DAN ALAMAT KLINIK TING'S CLINIC No. 101, Jalan Kampung Nyabor 96007 Sibu, Sarawak SIBURAN UNION CLINIC 62, Siburan Bazaar 17th Mile Kuching-Serian Road 94200 Kuching, Sarawak LING'S MEDICAL CENTRE No. 2, Lot 347, Mayland Building 98050 Marudi, Sarawak LEE CLINIC No. 52, Ground Floor, Serian Bazaar 94700 Serian, Sarawak KLINIK WONG CHING SHE GF, No. 139, Jalan Masjid Taman Sri Dagang 97000 Bintulu KLINIK YEW 38, Jalan Market 96000 Sibu, Sarawak KLINIK TONY SIM TONG AIK Lot 1105, Jalan Kwong Lee Bank 93450 Kuching KLINIK TEO No. 50 Kenyalang shopping Centre Jalan Sion Kheng Hong 93300 Kuching KLINIK SIBU 17 & 19 Workshop Road 96008 Sibu, Sarawak KLINIK ROBERT WONG No. 143, Jalan Satok 93000 Kuching KLINIK JULIAN WEE No. 312, Pandungan Road 93100 Kuching KLINIK EVERBRIGHT No. 30 Everbright Park Shophouse 3rd Mile Jalan Penrissen 93250 Kuching KLINIK DR. WONG Lot 47, Jalan Masjid Lama 96100 Sarikei, Sarawak KLINIK CYRIL SONGAN Lot 2044, Kota Sentosa 93250 Kuching KLINIK DOMINIC SONGAN No. 37, Jalan Tun Ahmad Zaidi Addruce 93400 Kuching HELEN NGU SURGERY AND CLINIC FOR WOMEN No. 251, Lot 2579, Central Park Commercial Centre, 3rd Mile 93200 Kuching, Sarawak CHONG'S CLINIC No. 3, Jalan Trusan 98850 Lawas C.S. LING EYE SPECIALIST CENTRE Lot 180, Ground Floor Jalan Song Thian Cheok 93100 Kuching C.M. WONG SPECIALIST CLINIC FOR WOMEN Lot 255 Sect. 8 KTL, Jalan Hj. Taha 93400 Kuching C.L. WONG HEART & MEDICAL SPECIALIST CLINIC Lot 256, Section 8 KTLD Jalan Hj. Taha 93400 Kuching HU'S SPECIALIST CLINIC 1B Brooke Drive 96000 Sibu, Sarawak KLINIK MALAYSIA G20 King Hua Shopping Complex Wong Nai Siong Road 96000 Sibu, Sarawak DR. -

2020 Edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Introduction 02 Company Details Core Business 03 • 3.1 Switchboard Manufacturing • 3.2 Solar Photovoltaic System Design and Build • 3.3 System Integration • 3.4 Switchboard Maintenance 04 Completed Projects 05 Ongoing Projects 06 List of License and Registrations 01 INTRODUCTION unvision Engineering Sdn Bhd was founded in January 2013 and has its core business as S a Systems Integrator for SCADA/Telemetry Supervisory and Control for water treatment plants, sewage treatment plants as well as factory automation projects. We strive to maintain the highest standards in designing and manufacturing control systems to meet the requirements of our clients. Backed up with speedy after sales service, we hope to emerge as an important player in industrial automation in Sarawak for the years to come. Leveraging on 30 years of experience in switchboard manufacturing and related electrical works of its parent companies, Tytronics Sdn Bhd and Powertech Engineering, Sunvision Engineering is in a position to offer turnkey solutions for industrial or building automation. We are capable of designing, supplying and commissioning SCADA/Telemetry control complete with Main Switchboards and Starter Control Panels. Page 1 of 16 02 COMPANY DETAILS Name of Company Scope of Experties: Sunvision Engineering Sdn Bhd Switchboard Manufacturing Company Registration No. PLC and SCADA HMI Design and Programming 1030594-H Remote Telemetry/Monitoring System Design GST Registration No. 000292618240 Industrial Wireless Systems (Wi-Fi, 3G, GPRS, GSM) Date of Establishment Control System Design January 2013 Solar Photovoltaic Design and Build Registered Address Lot 846, Sublot 127, Block 8, Jalan Demak Contact details: Maju 1A1, Muara Tebas Land District, Phone: 082-432650/082-432651 Demak Laut Industrial Park (Phase 3), Fax: 082-432652 Jalan Bako, 93050 Kuching, Sarawak. -

S'wak B'tin.Vol 3

Volume 3, Issue 1 Page 2 Volume 3, Issue 1 C H Williams Talhar Wong & Yeo Sdn. Bhd. (24706-T) January - March, 2005 MIRI – THE OIL TOWN OF SARAWAK (CONT’D) Population PPK 344/6/2005 “Work Together With You” Miri District has about 11% of the total population of Sarawak in 2000 and has surpassed Sibu in the last decade to become the 2nd largest District after Kuching. Its growth of 5.05% and 3.85% per annum in the last 2 decades respectively and its urbanization rate of 76.5% is amongst the highest in the State (Source : Population Census 2000) MIRI – THE OIL TOWN OF SARAWAK About 55% of Miri’s population range from 15 to 40 years old. This is a relatively young and vibrant group. Area of Miri Division 26,777 sq km Shopping Complexes Area of Miri District 4,707 sq km Population of Miri 304,000 At present, Miri has seven (7) shopping complexes, most of which are located in the urban-city center areas. They are among the newer Divisional Town Miri and more modern complexes in Sarawak as most of them were built during the mid 1990’s: District Town Marudi Major industries Timber-based industries, Shopping Complexes in Miri shipbuilding and offshore repair works, oil refinery YEAR NO. OF RETAIL NO. OF Natural Feature Mulu Caves, Lambir Waterfall, Mt Murud, COMPLEX LOCATION FLOOR SPACE AREA (S.M) COMPLETED LEVELS UNITS Bario Highlands Landmark The Grand Old Lady - Sarawak’s EXISTING COMPLEXES first oil rig 1 WISMA PELITA TUNKU City Center 1985 4 80 8,133.00 2IMPERIAL MALL City Center 1997 4 148 18,335.70 3SOON HUP TOWER City Center 1992 5 67 12,636.80 4BINTANG PLAZA City Center 1996 5 132 20774.60 (proposed to be extended to 30658 sm) 5 MIRI PLAZA Suburban 1994 4 39 3,655.20 6 BOULEVARD SHOPPING COMPLEX Suburban 1999 4 114 19,045.00 7M2 Suburban 2003 3 49 15,950.00 Aerial view of residential estates at Permyjaya, Tudan, Lutong/Senadin and Piasau/Pujut, Miri. -

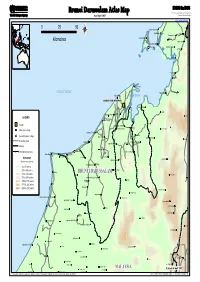

Brunei Darussalam Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Brunei Darussalam Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of April 2007 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected] 0 25 50 Lumat ((( Kampong Lambidan ((( ((( Kpg Manggis ((( ((( Kasaga ((( ((( ((( Kampong Lukut ((( ((( Bea Kpg Ganggarak ((( ((( Bentuka kilometres ((( Padas Valley ((( Kpg Menumbok ((( ((( !! Victoria Kampong Suasa ((( Lumadan ((( Weston ((( Brunei_Darussalam_Atlas_A3LC.WOR Mesapol ((( ((( Sipitang ((( Pekan Muara ((( PACIFIC OCEAN Kpg Banting ((( Malaman Kpg Jerudong Sungai Brunei ((( BANDARBANDAR SERISERI BEGAWANBEGAWAN ( Sundar Bazaar ((( ((( Lawas ((( Kampong Kopang (((Kpg Kilanas ((( LEGEND ((( ((( Ulu Bole ((( Pekan Tutong Trusan ((( Capital Kampong Gadong ((( ((( ((( Limbang ((( ((( Kampong Limau Manis ((( Kampong Belu !! Main town / village Kampong Telamba ((( ((( ((( Bangar Secondary town / village Kpg K Abang ((( Kpg Kuala Bnwan ((( ((( Meligan ((( Secondary road Kpg Lumut ((( Kampong Baru Baru ((( ((( Kpg Batu Danau ((( Bakol Railway ((( Bang Tangur ( !! ((( International boundary !! Pekan Seria Kpg Lepong Lama ((( ((( Kuala Baram ((( Kuala Belait ((( ((( Kampong Rentis ((( Bukit Puan ((( Kpg Medit ELEVATION Long Lutok ((( Kampong Ukong ((( (Above mean sea level) Kampong Sawah ((( 0 to 250 metres 250 to 500 metres ((( Rumah Supon ((( Lutong BRUNEIBRUNEI DARUSSALAMDARUSSALAM 500 to 750 metres ((( ((( Belait ((( ((( Pa Berayong ((( 750 to 1000 metres Kampong Kerangan Nyatan ((( ((( L ((( Bandau 1000 to 1750 metres Kpg Labi ((( 1750 to 2500 metres ((( Miri -

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission

MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION INVITATION TO REGISTER INTEREST AND SUBMIT A DRAFT UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLAN AS A UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVIDER UNDER THE COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA (UNIVERSAL SERVICE PROVISION) REGULATIONS 2002 FOR THE INSTALLATION OF NETWORK FACILITIES AND DEPLOYMENT OF NETWORK SERVICE FOR THE PROVISIONING OF PUBLIC CELLULAR SERVICES AT THE UNIVERSAL SERVICE TARGETS UNDER THE JALINAN DIGITAL NEGARA (JENDELA) PHASE 1 INITIATIVE Ref: MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Date: 20 November 2020 Invitation to Register Interest as a Universal Service Provider MCMC/USPD/PDUD(01)/JENDELA_P1/TC/11/2020(05) Page 1 of 142 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................. 4 INTERPRETATION ........................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION I – INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 8 1. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 8 SECTION II – DESCRIPTION OF SCOPE OF WORK .............................................................. 10 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FACILITIES AND SERVICES TO BE PROVIDED ....................................................................................................................................... 10 3. SCOPE OF -

5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 For

Aliran Monthly : Vol.31(3) Page 1 For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2011(026665) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 COVER STORY Making sense of the forthcoming Sarawak state elections Will electoral dynamics in the polls sway to the advantage of the opposition or the BN? by Faisal S. Hazis n the run-up to the 10th all 15 Chinese-majority seats, spirit of their supporters. As III Sarawak state elections, which are being touted to swing contending parties in the com- II many political analysts to the opposition. Pakatan Rakyat ing elections, both sides will not have predicted that the (PR) leaders, on the other hand, want to enter the fray with the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) will believe that they can topple the BN mentality of a loser. So this secure a two-third majority win government by winning more brings us to the prediction made (47 seats). It is likely that the coa- than 40 seats despite the opposi- by political analysts who are ei- lition is set to lose more seats com- tion parties’ overlapping seat ther trained political scientists pared to 2006. The BN and claims. Which one will be the or self-proclaimed political ob- Pakatan Rakyat (PR) leaders, on likely outcome of the forthcoming servers. Observations made by the other hand, have given two Sarawak elections? these analysts seem to represent contrasting forecasts which of the general sentiment on the course depict their respective po- Psy-war versus facts ground but they fail to take into litical bias. Sarawak United consideration the electoral dy- People’s Party (SUPP) president Obviously leaders from both po- namics of the impending elec- Dr George Chan believes that the litical divides have been engag- tions. -

Why Governments Fail to Capture Economic Rent

BIBLIOGRAPHICINFORMATION Why Governments Fail to Capture Economic Rent: The Unofficial Appropriation of Rain Forest Title Rent by Rulers in Insular Southeast Asia Between 1970 and 1999 Source http://www.geocities.com/davidbrown_id/Diss/DWB.Fintext.doc Author 1 Brown, David Walter Author 2 NA Author 3 NA Publication/Conference Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation Edition NA Document Type Dissertation CPI Primary Subject East Malaysia CPI Secondary Subject Political economy; Sabah ; Sarawak; Geographic Terms Sabah; Sarawak Abstract NA CentreforPolicyInitiatives(CPI) PusatInitiatifPolisi http://www.cpiasia.org 1 Chapter 1 Introduction The world’s tropical rain forests are important socially and environmentally as well as by virtue of their contributions to economic growth. As these forests are logged, their social values as generators of rural incomes and their environmental services as biodiversity reserves, carbon sinks, soil reserves, and watersheds tend to diminish. Despite these facts, most governments in the tropics are unable to resist logging these forests in favor of national economic objectives, including: creation of a forest industrial sector, higher employment, positive balance of payments, and increased government revenues. However, given the high economic stakes that can be obtained from their forests, it is seems counterintuitive that tropical governments rarely succeed in optimally harnessing government revenue from this valuable natural resource. This staggering loss of revenue to developing countries obviously has important implications for economic development. Timber revenue could be used, for example, to finance the kind of strategic industrial policies that allow the high performing Asian economies to achieve high levels of economic growth. This dissertation argues that states with rain forests are often unable to collect optimal revenue from the massive profit earned by timber companies that harvest state forests because this profit already has a hidden destination. -

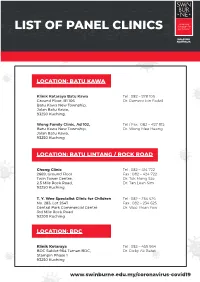

SUTS Panel of Clinics Cvd19 (Revised 31032021)

LIST OF PANEL CLINICS LOCATION: BATU KAWA Klinik Kotaraya Batu Kawa Tel : 082 – 578 106 Ground Floor, B1 106 Dr. Ramzee bin Fadzil Batu Kawa New Township, Jalan Batu Kawa, 93250 Kuching. Wong Family Clinic, Ad 102, Tel / Fax : 082 – 457 815 Batu Kawa New Township, Dr. Wong Mee Heang Jalan Batu Kawa, 93250 Kuching LOCATION: BATU LINTANG / ROCK ROAD Chong Clinic Tel : 082 – 414 722 2669, Ground Floor Fax : 082 – 424 722 Twin Tower Centre, Dr. Tok Mang Sze 2.5 Mile Rock Road, Dr. Tan Lean Sim 93250 Kuching T. Y. Wee Specialist Clinic for Children Tel : 082 – 234 626 No. 283, Lot 2647 Fax : 082 – 234 625 Central Park Commercial Centre Dr. Wee Thian Yew 3rd Mile Rock Road 93200 Kuching LOCATION: BDC Klinik Kotaraya Tel : 082 – 459 964 BDC Sublot 964 Taman BDC, Dr. Ricky Ak Batet Stampin Phase 1 93250 Kuching www.swinburne.edu.my/coronavirus-covid19 LOCATION: KOTA SAMARAHAN Klinik Desa Ilmu Tel / Fax : 082 – 610 959 No. 2, Lot 4687, Dr. Hafizah Hanim bt Desa Ilmu Jalan Datuk Mohd Musa Mohamed Abdullah 94300 Kota Samarahan LOCATION: MATANG / PETRA JAYA / SATOK Healthcare Clinic Petra Jaya Tel / Fax : 082 – 511 164 Ground Floor, No. 25, Lot 4306 Dr. Sadiah Bte Mohamad Ali Sukma Commercial Centre Jalan Sultan Tengah 93050 Kuching Ibukota Clinic Petra Jaya Tel / Fax : 082 – 441 034 Tingkat Bawah, Lot 5206 Dr. Aini Bin Murni Sublot 8, Block 18 Bangunan Shah Nur, Jalan Astana 93050 Petra Jaya Kuching Klinik Dr. Kon (Perubatan dan Kulit) Tel / Fax : 082 – 424 996 No. 19G, Lot 503, Ground Floor, Dr.