Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divulgação Bibliográfica

Divulgação bibliográfica Julho/Agosto 2019 Biblioteca da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra Sumário BASES DE DADOS NA FDUC ........................................................................................ 4 E-BOOKS .................................................................................................................. 6 MONOGRAFIAS ........................................................................................................ 52 Ciências Jurídico-Empresariais................................................................................................................. 53 Ciências Jurídico-Civilísticas ..................................................................................................................... 70 Ciências Jurídico-Criminais ...................................................................................................................... 79 Ciências Jurídico-Económicas .................................................................................................................. 82 Ciências Jurídico-Filosóficas ..................................................................................................................... 83 Ciências Jurídico-Históricas ..................................................................................................................... 88 Ciências Jurídico-Políticas ........................................................................................................................ 94 Vária ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Lutie Lytle 2019 Program

PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 1 13th Annual LUTIE A. LYTLE Black Women Law Faculty Workshop & Writing Retreat June 19-26, 2019 | University Park, PA 2 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT Claiming the Power of our Sisterhood 2019 Lutie Lytle Workshop and Retreat hosted on the campus of Penn State Law in the Lewis Katz Building, University Park, PA. Illustration credit: Mary Szmolko Cover photos credit: Penn State PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 13TH ANNUAL LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP AND WRITING RETREAT Hosted by: Penn State Law June 19-26, 2019 Welcome 4 Sponsors 6 About Our Honoree - 2019 Lutie A. Lytle Outstanding Scholar Award 7 About the Guest Speakers 8 Workshop & Writing Retreat Schedule 10 Participants 19 Committee Members 27 4 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT WELCOME FROM THE DEAN The Lutie Lytle Conference was mentoring and support for founded after a small number of scholarship, teaching, and service black women faculty, organized by for Lutie participants. I am so Professor Imani Perry, grateful that Professor Brown is collaborated at the Chicago home a part of the Penn State Law and of Professor Michele Goodwin. The School of International Affairs first official conference was held community. In addition to her at the University of Iowa College many contributions to the two of Law and was organized by then schools, the Rock Ethics Institute, Professor and now Dean Angela and the broader Penn State Onwauchi-Willig. The vision of community, she has done an the original collaboration and the outstanding job fundraising and first conference continue to guide organizing this event. -

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 8

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 814-865-5047 | Email: [email protected] | Twitter: @jillengle LEGAL TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE LAW: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Prof. of Clinical Law, 2007-present Reporting directly to the Dean, I am the law school’s primary academic officer, coordinating all academic and curricular matters and overseeing student disciplinary actions. The role includes responsibility for the integrity of our academic programs, and its ongoing management, delivery, and assessment. I serve as a key advisor to the Dean on the administration of the law school, develop and manage our course schedules, hire and manage all adjunct and visiting instructors, assess and implement new curricular offerings like our Concentrations (adding a new Race, Equity, & the Law Concentration in 2020). I am the Director of Penn State Law’s Joint Degree programs. I also teach Professional Responsibility, and Intersectionality & the Law. Prior to my associate deanship, I directed our Family Law Clinic, which I opened in January 2010. I managed the Clinic’s Supervising Attorney and our students, who work on domestic violence and other family cases in the local courts. I developed and taught the Clinic seminar, and I previously taught Family Law, and Externships. I extensively redesigned our Externships curriculum, adding an “Externships Everywhere” course, paid externships, and remote externships. For five years I directed our Public Interest programs; and I helped launch our Mindfulness in Law Society in 2018 and our George Floyd Memorial Scholarship in 2020. OTHER TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATIONS: Adjunct Faculty, Media Law, 2002-2004. -

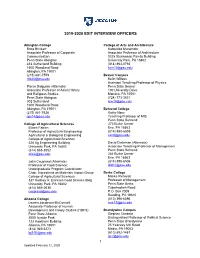

2019-2020 Exit Interview Officers 1

2019-2020 EXIT INTERVIEW OFFICERS Abington College College of Arts and Architecture Ross Brinkert Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Corporate Associate Professor of Architecture Communication 0325 Stuckeman Family Building Penn State Abington University Park, PA 16802 414 Sutherland Building (814) 863-0793 1600 Woodland Road [email protected] Abington, PA 19001 (215) 881-7579 Beaver Campus [email protected] Keith Willson Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics Pierce Salguero (Alternate) Penn State Beaver Associate Professor of Asian History 100 University Drive and Religious Studies Monaca, PA 15061 Penn State Abington (724) 773-3831 302 Sutherland [email protected] 1600 Woodland Road Abington, PA 19001 Behrend College (215) 881-7826 Kathy Noce [email protected] Teaching Professor of MIS Penn State Behrend College of Agricultural Sciences 273 Burke Center Eileen Fabian Erie, PA 16563 Professor of Agricultural Engineering (814) 898-6508 Agricultural & Biological Engineering [email protected] College of Agricultural Sciences 228 Ag Engineering Building David Dieteman (Alternate) University Park, PA 16802 Associate Teaching Professor of Management (814) 865-3552 Penn State Behrend [email protected] 264 Burke Center Erie, PA 16563 John Coupland (Alternate) (814) 898-6506 Professor of Food Science; [email protected] Undergraduate Program Coordinator Chair, Ingredients as Materials Impact Group Berks College College of Agricultural Sciences Malika Richards 337 Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Bldg Professor of Management University Park, PA 16802 Penn State Berks -

Penn State University Public School Code of 1949 Volume 1

Public School Code of 1949 Volume I Compiled by: University Budget Office 308 Old Main University Park, PA 16802 December 2017 Table of Contents Volume I Introduction .................................................................... Tab A Summary Schedules ....................................................... Tab B Operating Budget – 2017-18........................................... Tab C Employee Headcounts and Salary Data .......................... Tab D Non-Salary Compensation .............................................. Tab E University Retirement Policies ........................................ Tab F Tuition Grant-in-Aid ....................................................... Tab G 2016-17 Travel Expenditures.......................................... Tab H Volume II Actual Operating Expenditures - 2016-17 Volume III Goods and Services Expenditures J:\STAIRS\STAIRS 2017\STAIRS VOL. 1 TOC.DOCX 11/21/17 TAB A Introduction THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY Public School Code of 1949 December 2017 Public School Code of 1949, requires that Penn State submit a report within 180 days of the close of the university’s current fiscal year. The 2016-17 fiscal year closed on June 30, 2017. Therefore, this report is submitted in compliance with the above mentioned House Bill, which specified that the University provide the following: (A1) Revenue and expenditure budgets of the university’s academic and administrative support units for the current fiscal year. (A2) The actual revenue and expenditures for the prior year in the same format as the information reported above. (A3) For any defined project or program which is the subject of a specific line item appropriation from the General Fund, the university shall disclose the following: (A3i) Revenue and expenditure budgets of the defined program or project for the current fiscal year. (A3ii) The actual revenue and expenditures of the defined program or project for the prior year in the same format as the information reported under paragraph a1. -

Thedickinson

38644out 4/1/10 2:45 PM Page 1 The Dickinson Lawyer The Dickinson School of Law Celebrating 175 Years of Excellence Penn State UniverSity DickinSon School of law alUmni magazine — winter 2010 38644out 4/1/10 2:25 PM Page 2 A L ETTER FROM THE DEAN An anniversary event is as much a time to look to the future as it is to celebrate the past. A special pull-out section of this issue of The Dickinson Lawyer features a 175-year timeline with milestones that reflect how The Dickinson School of Law has helped shape our region, our country, and our world. The section ends with a photo “walk through” of our new and renovated facilities in Carlisle which will be dedicated on April 16. Together with our award-winning Lewis Katz Building at University Park, our new facilities provide our students with several unique advantages. In our courtroom, for example, students were recently able to observe Judge D. Brooks Smith ’76 as part of a Third Circuit panel hearing a last-minute death penalty appeal. In our classrooms, students compare con - stitutional issues with their peers in South Africa and Australia. In our library, students have 24/7 access to a vast collection of resources that puts answers at their fingertips. We’re also celebrating the 30-year anniversary of our clinical program, which began in earnest with our Family, Disability and Arts, Sports and Entertainment Law clinics. In 2008, we expanded our clinics to include opportunities for students to work on immigration and civil rights issues on a national level. -

Megan S. Wright [email protected] O: 814-865-8957 M: 801-755-7226

Wright 4/8/21 1 Megan S. Wright [email protected] O: 814-865-8957 M: 801-755-7226 ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS The Pennsylvania State University, 2018-present Assistant Professor, Penn State Law, University Park Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health Sciences, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey Affiliate Faculty, Department of Sociology and Criminology, College of the Liberal Arts, University Park Affiliate Faculty, The Rock Ethics Institute, University Park Weill Cornell Medical College Adjunct Assistant Professor of Medical Ethics in Medicine, 2020-present Postdoctoral Associate of Medical Ethics, 2016-2018 Summer Research Associate, 2015 Solomon Center for Health Law & Policy (Yale Law School) Research Fellow and Senior Advisor to Brain Injury Project, 2016-2018 James E. Rogers College of Law (University of Arizona) Law and Social Science Research Fellow, 2012-2013 Southwest Institute for Research on Women (University of Arizona) Qualitative Analyst, 2012-2013 EDUCATION Yale Law School, J.D., 2016 University of Arizona, Ph.D. in Sociology, 2012 University of Arizona, M.A. in Sociology, 2006 Brigham Young University, B.S. in Sociology, 2003 • Magna cum laude PUBLICATIONS Healthcare Decision Making Legal Issues in Dementia, in THE BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY OF DEMENTIA (BRUCE MILLER & BRAD BOUVE eds. forthcoming), with Jalayne Arias and Ana Tyler. Equality of Autonomy? Physician Aid in Dying and Supported Decision Making, 63 ARIZ. L. REV. 157 (2021). Wright 4/8/21 2 Dementia, Cognitive Transformation, and Supported Decision Making, 20 AM. J. BIOETHICS 88 (2020). Dementia, Autonomy, and Supported Healthcare Decision Making, 79 MD. -

Exit Interview Officers

EXIT INTERVIEW OFFICERS Abington College Beaver Campus Judy Ozment Keith Willson Associate Professor of Chemistry Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics Penn State Abington Penn State Beaver 328 Woodland 100 University Drive 1600 Woodland Road Monaca, PA 15061 Abington, PA 19001 (724) 773-3831 (215) 881-7518 [email protected] [email protected] Behrend College College of Agricultural Sciences Lena Surzhko-Harned Robert Weaver Assistant Teaching Professor, Political Professor of Agricultural Economics Science College of Agricultural Sciences Penn State Behrend 201-C Armsby 149 Kochel Center University Park, PA 16802 Erie, PA 16563 (814) 865-3746 (814) 898-6074 [email protected] [email protected] John Coupland (Alternate) Fred Nitterright (Alternate) Professor of Food Science; Assistant Teaching Professor of Engineering Undergraduate Program Coordinator Penn State Behrend Chair, Ingredients as Materials Impact Group 227 Burke Center College of Agricultural Sciences Erie, PA 16563 337 Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Bldg (814) 898-6185 University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] (814) 865-2636 [email protected] Berks College Malika Richards Altoona College Professor of Management Lauren Jacobson-McConnell Penn State Berks Associate Professor of Human Tulpehocken Road Development and Family Studies (HDFS) P.O. Box 7009 Penn State Altoona Reading, PA 19610 3000 Ivyside Park (610) 396-6096 123 Hawthorn Building [email protected] Altoona, PA 16601 (814) 949-5273 Brandywine Campus [email protected] Stephen Cimbala Distinguished Professor of Political Science College -

Certifying Officials

PENN STATE VA CERTIFYING OFFICIALS CAMPUS CERTIFYING OFFICIAL(S) MAILING ADDRESS Abington (AB) Penn State Abington 215-881-7386 Tim Smalarz (tjs421) Office of the Registrar 215-881-7625 (fax) Sutherland 118 1600 Woodland Rd Abington, PA 19001 Altoona (AL) Penn State Altoona 814-949-5282 Jean Lasinski (jxf15) C105 Smith Building 814-949-5055 David Pearlman (dpp1) 3000 Ivyside Park 814-949-5011 (fax) Altoona, PA 16601 Beaver (BR) Penn State Beaver 724-773-3803 Gail Gray (geg6) 102A RAB 724-773-3808 Debra Seidenstricker (dls5815) 100 University Drive 724- 773-3658 (fax) Monaca, PA 15061 Berks (BK) Penn State Berks 610-396-6036 Antoinette (Nettie) Matz (acc16) Perkins Student Center 610-396-6073 Ryley Daniels (rbd5264) P.O. Box 7009 610-396-6070 Main Office Reading, PA 19610-6009 Correspondence to: BerksFinAid@psu Brandywine (BW) Penn State Brandywine 610-892-1260 Robyn Pettiford (rup235) Office of Student Aid 610-892-1261 Diaonne Taylor (dmt5394) 25 Yearsley Mill Road 610-892-1238 (fax) Media, PA 19063 DuBois (DS) Penn State DuBois 814-372-3043 Tharren Thompson (tjt15) 1 College Place 814-375-4726 Dan Bowman (dbb5285) 214 DEF Building 814-372-3007 (fax) DuBois, PA 15801 Erie (ER) - Behrend Penn State Erie 814-898-6335 Giselle Hudson (gth1) The Behrend College 814-898-6869 Emily Thompson (eas29) 4851 College Drive 814-898-7595 (fax) Erie, PA 16563 Fayette (FE) 724-430-4203 Abby Keefer (amk6112) Penn State Fayette 724-430-4138 Mike Romeo (mjr356) The Eberly Campus 724-430-4175 (fax) 108A Williams Building Lemont Furnace, PA 15456 Greater Allegheny (GA) Penn State Greater Allegheny 412-675-9016 Dave Davis (djd29) Student Services Office 412-675-9090 Kathy Hill (kah85) 124 Frable Building 412-675-9056(fax) McKeesport, PA 15133 Great Valley (GV) 610-648-3343 Linda Salavarrie (lps5429) Penn State Great Valley 610-648-3275 Elizabeth delValle (emd3) Office of Student Aid Correspondence to: [email protected] 30 E. -

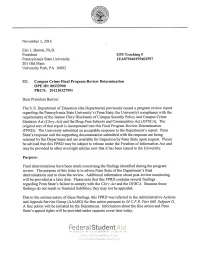

Final Program Review Determination November 3, 2016

Prepared for: Pennsylvania State University OPE ID: 00332900 PRCN: 201210327991 Prepared by: U.S. Department of Education Federal Student Aid Clery Act Compliance Team Final Program Review Determination November 3, 2016 www.FederalStudentAid.ed.gov Pennsylvania State University Campus Crime Final Program Review Determination- Page #1 Table of Contents A. The Clery Act and the Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act .................................... 2 B. Institutional Information ...................................................................................................... 4 C. Background and Scope of Review ........................................................................................ 5 D. Findings and Final Determinations ................................................................................... 16 Finding #1: Clery Act Violations Related to the Sandusky Matter ......................................... 16 Finding #2: Lack of Administrative Capability ....................................................................... 38 Finding #3: Omitted and/or Inadequate ASR and AFSR Policy Statements ........................... 45 Finding #4: Failure to Issue Timely Warnings in Accordance with Federal Regulations ....... 61 Finding #5: Failure to Properly Classify Reported Incidents and Disclose Crime Statistics .. 77 Finding #6: Failure to Establish an Adequate System for Collecting Crime Statistics from All Required Sources ................................................................................ 108 Finding -

Why She Relays

Football cornerback John Reid out for 2017 season. See Page 5. Vol. 117, No. 135 Friday, April 7, 2017 WHYRelay for Life overallSHE Melanie Kamil relaysRELAYS in honor of her mother By Allison Moody “I would always tell FOR THE COLLEGIAN her that I wished When Melanie Kamil was six that there was years old, her mother was diag- nosed with stage three ovarian something I could cancer. Each time she went into do, and she would remission, the cancer came back. It was during her first month answer by saying at Penn State, February 2015 that ‘all that I care about Kamil got a call from her aunt — “You need to come say your good- is that you are here byes.” with me.’” It was her mother’s life — and death — that inspired Kamil’s Melanie Kamil involvement and ferocious dedi- Relay for Life Overall cation to Relay for Life of Penn State. She started as a speaker and her spine. This lead to more at the luminaria ceremony about chemotherapy throughout 2013 a month after her mother’s and 2014. Natalie Runnerstrom/Collegian passing and has worked her way “I would always tell her that I to holding a merchandise overall wished that there was something The stage for Relay For Life in the HUB-Robeson Center on Saturday, April 9, 2016. position. I could do, and she would answer by saying ‘all that I care about the treatment was working, she “We talked about memories Living with a survivor is that you are here with me,’” was too weak for anymore chemo, over the years, how much we Kamil’s mother, Stephanie, Kamil said in her speech. -

About Penn State 1

About Penn State 1 d. Such other responsibilities as law, governmental directives, or ABOUT PENN STATE custom require the Board to act upon. 3. The Board of Trustees shall inform the citizens of the Commonwealth This is Penn State of Pennsylvania of the University's performance of its role in the education of the youth of Pennsylvania. Penn State is in the top 1 percent of universities worldwide and has the largest alumni network in the nation. Founded in 1855, the University 4. The Board of Trustees shall assist the President in the development combines academic rigor with a vibrant campus life as it carries out its of effective relationships between the University and the various mission of teaching, research, and service with pride and focuses on the agencies of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the United future throughout Pennsylvania and the world. Granted the highest rating States of America which provide to the University assistance and for research universities by the Carnegie Foundation, Penn State teaches direction. students to be leaders with a global perspective. MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES (https:// Our leadership in administration, faculty, and staff make our mission trustees.psu.edu/) come alive every day. The Board of Trustees reviews and approves the budget of the University and guides general goals, policies, and President's Council procedures from a big-picture perspective. The President’s office ensures • Eric J. Barron, President (https://president.psu.edu) that all aspects of the University are running smoothly and promotes • Nicholas P. Jones, Executive Vice President and Provost (https:// overall principles that students, faculty, and staff abide by for the long provost.psu.edu/) term.