Final Program Review Determination November 3, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divulgação Bibliográfica

Divulgação bibliográfica Julho/Agosto 2019 Biblioteca da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra Sumário BASES DE DADOS NA FDUC ........................................................................................ 4 E-BOOKS .................................................................................................................. 6 MONOGRAFIAS ........................................................................................................ 52 Ciências Jurídico-Empresariais................................................................................................................. 53 Ciências Jurídico-Civilísticas ..................................................................................................................... 70 Ciências Jurídico-Criminais ...................................................................................................................... 79 Ciências Jurídico-Económicas .................................................................................................................. 82 Ciências Jurídico-Filosóficas ..................................................................................................................... 83 Ciências Jurídico-Históricas ..................................................................................................................... 88 Ciências Jurídico-Políticas ........................................................................................................................ 94 Vária ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability

Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability Jasmin Kientzel Boekenplan ISBN 978 90 8666 377 4 Copyright © 2015 Jasmin Kientzel Published by Boekenplan, Maastricht, the Netherlands Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability Dissertation to obtain the degree of Doctor at Maastricht University, on the authority of the Rector Magnificus, Prof. dr. L.L.G. Soete, in accordance with the decision of the Board of Deans, to be defended in public on Wednesday 9 September 2015, at 16:00 hours By Jasmin Kientzel Promotor Prof. Dr. Gerjo Kok Co-supervisor Dr. Mindel van de Laar Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Harm Hospers (Chair) Prof. Dr. Piet Eichholtz Prof. Dr. Rob Ruiter Dr. Ruud Jonkers, Retired director of ResCon bv. iv Acknowledgments “Even if we could turn back, we’dprobably never end up where we started”. (Haruki Murakami, 1Q84) Drafting this dissertation has been a journey of discovery, and it would be almost impossible to list all the milestones, lessons learned and limits encountered on the way. Just as everyone who embarks on a long journey into the wild, the experience itself has afforded me a wealth of knowledge about the world around me and my role in it and more than I had thought previously possible. The biggest revelation was that no stage of this journey would have been possible without the many people whose support ensured my continuing even when I seemed to have hit a roadblock: Without their encouragements and understanding I would not be writing this acknowledgment. I would like to express my special appreciations and thanks to my two supervisors, Professor Dr. -

Penalties for Hospital Acquired Conditions

Penalties For Hospital Acquired Infections Kaiser Health News Penalties For Hospital Acquired Conditions Medicare is penalizing hospitals with high rates of potentially avoidable mistakes that can harm patients, known as "hospital-acquired conditions." Penalized hospitals will have their Medicare payments reduced by 1 percent over the fiscal year that runs from October 2014 through September 2015. To determine penalties, Medicare ranked hospitals on a score of 1 to 10, with 10 being the worst, for three types of HACs. One is central-line associated bloodstream infections, or CLABSIs. The second if catheter- associated urinary tract infections, or CAUTIs. The final one, Serious Complications, is based on eight types of injuries, including blood clots, bed sores and falls. Hospitals with a Total HAC Score above 7 will be penalized. Source: Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services Serious Compli Total Provider cations CLABSI HAC ID Hospital City State County Score Score CAUTI Score Score Penalty 20017 Alaska Regional Hospital Anchorage AK Anchorage 7 9 10 8.625 Penalty 20001 Providence Alaska Medical Center Anchorage AK Anchorage 10 9 6 8.375 Penalty 20027 Mt Edgecumbe Hospital Sitka AK Sitka 7 Not Available Not Available 7 No Penalty 20006 Mat-Su Regional Medical Center Palmer AK Matanuska Susitna 10 6 3 6.425 No Penalty 20012 Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Fairbanks AK Fairbanks North Star 9 8 1 6.075 No Penalty 20018 Yukon Kuskokwim Delta Reg Hospital Bethel AK Bethel 6 Not Available Not Available 6 No Penalty 20024 Central Peninsula General -

Penn State Faculty and Staff Contribution Form

Penn State Faculty and Staff Contribution Fo rm Dr./Ms. Mrs./Mr. Name: First Middle Last Unit/College/Campus Home Address Campus Address City City State Zip Title Email I am a Penn State graduate, class of Home Phone If alumna and married, please enter your name before marriage if Penn State ID Number different from your present name Gift Designations See suggestions on reverse Enter the designation(s) for your gift and the portion of your gift that each should receive. (Please make sure the individual gift amounts equal your total gift.) 1._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* 2._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* 3._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* Total (all designations/pay period) ............................................................................................................................... $____________ .00 Total per pay period *Amount per pay period if payroll deduction, otherwise total of gift per designation Three Ways to Make a Gift I Payroll deduction I a new payroll deduction donor Effective -

Branstetter, Jennifer Sent

Branstetter, Jennifer ·From: Ammerman, Paula~ Sent: Wednesday, Janua~ Subject: JVP statement/attorney-client privilege Importance: High Rod Erickson asked that I distribute the below message to you. g To Board Members: r Below is a message I'm planning to send outto the Penn State community on Friday morning. Please let me know.o if you have any reservations· about this message or any edits to offer. Lanny has edited this statement from an earlier version. Please send any comments to Paula by noon tomorrow (Thursday). d Thanks, n Rod u ef This week has been filled with both mourning and celebration of the contributionsn of Joseph Vincent Paterno. I first want to offer my sincere condolences to his wife Sue, his children andi their families. While we knew the public educator, football coach and philanthropist, his family knew himh intimately as husband, father and . grandfather. During an interview a few years back, he was asked whats was his secret ambition. His reply, "To Je a good father and grandfather." I ask all members ofthe Penn State community to respect the family's privacy as they mourn the loss of their loved one, and continuen to support the Paternos with your thoughts and prayers. u Much has been written through the decades about Joes Paterno's life and his iconic coaching career. He will always be remembered for his "Grand Experiment"e of combining academic excellence with championship caliber athletic.performance. This approach sett a new standard for all intercollegiate programs around the · nation, and became known as the Penn Statea way-- "Success with Honor." The stellar graduation rate of Joe's players and all Penn State student-athletesst can be traced to his emphasis on scholarship. -

Gary a Abdullah Resume

Gary A. Abdullah [email protected] 206 Carnegie Building University Park, PA 16802 814-883-0980 EDUCATION: The Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA M.A. - Telecommunication Studies, May 2007 The Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA B.A. - Telecommunications, May 2003 RELEVANT EXPERIENCE: July 2017- Assistant Dean of Diversity and Inclusion (Academic Administrator), Donald P. Current Bellisario College of Communications The Pennsylvania State University; University Park, PA ● Oversee administrative and programmatic Functioning oF student support services For students From traditionally under-represented groups as they relate to gender, race, ethnicity, condition oF ability, sexual orientation and gender identity, and socio- economic status ● Responsible For strategic planning and For the implementation and management of programs designed to recruit, retain, and support diverse pools of undergraduate and graduate students. ● Responsible For identiFying and securing grants and other sources oF Funding that will directly support various diversity initiatives throughout the college. ● Seek partnerships with minority-serving institutions, secondary schools, and Federal and state programs that might be sources oF talented and motivated students, stafF, and Faculty From underrepresented groups ● Advise student organizations that promote diversity and inclusion within the College ● Instruct a First-year Seminar each fall and spring semester ● Provide students with academic advising, as needed December 2013- Multicultural -

Penn Staters

The Mount Nittany Society Rising above State College and the University Park campus, Mount Nittany has inspired awe and pride for generations of Penn Staters. Named for this cherished natural landmark, the Mount Nittany Society represents the pinnacle of philanthropy to Penn State. From the inaugural group of 149 members in 1977, to the Celebrating more than 1,700 supporters recognized today, the members Penn State’s of the Mount Nittany Society have demonstrated a level of Philanthropic generosity towards Penn State that has been nothing less “You see Penn State as a than remarkable. The aim of the Society is to celebrate those place where opportunity Leaders individuals whose philanthropy is having the greatest impact is realized, you know what across the University through gifts to any and every aspect Penn Staters are capable of, of our mission. As the University’s top donors, members of and you understand that you the Mount Nittany Society are taking the lead in making Penn play a critical role in making State an even stronger institution for the twenty-first century. this great institution even greater. On behalf of all of The Mount Nittany Society celebrates those individuals Penn State, thank you for whose cumulative lifetime giving to Penn State has reached being a part of our history, or exceeded $250,000 in irrevocable commitments. Within our present and our future.” the Society, members of the Laurel Circle have achieved President Eric Barron, cumulative lifetime giving that has reached $1,000,000, while addressing the members members of the Elm Circle have reached $5,000,000. -

Lutie Lytle 2019 Program

PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 1 13th Annual LUTIE A. LYTLE Black Women Law Faculty Workshop & Writing Retreat June 19-26, 2019 | University Park, PA 2 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT Claiming the Power of our Sisterhood 2019 Lutie Lytle Workshop and Retreat hosted on the campus of Penn State Law in the Lewis Katz Building, University Park, PA. Illustration credit: Mary Szmolko Cover photos credit: Penn State PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 13TH ANNUAL LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP AND WRITING RETREAT Hosted by: Penn State Law June 19-26, 2019 Welcome 4 Sponsors 6 About Our Honoree - 2019 Lutie A. Lytle Outstanding Scholar Award 7 About the Guest Speakers 8 Workshop & Writing Retreat Schedule 10 Participants 19 Committee Members 27 4 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT WELCOME FROM THE DEAN The Lutie Lytle Conference was mentoring and support for founded after a small number of scholarship, teaching, and service black women faculty, organized by for Lutie participants. I am so Professor Imani Perry, grateful that Professor Brown is collaborated at the Chicago home a part of the Penn State Law and of Professor Michele Goodwin. The School of International Affairs first official conference was held community. In addition to her at the University of Iowa College many contributions to the two of Law and was organized by then schools, the Rock Ethics Institute, Professor and now Dean Angela and the broader Penn State Onwauchi-Willig. The vision of community, she has done an the original collaboration and the outstanding job fundraising and first conference continue to guide organizing this event. -

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 8

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 814-865-5047 | Email: [email protected] | Twitter: @jillengle LEGAL TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE LAW: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Prof. of Clinical Law, 2007-present Reporting directly to the Dean, I am the law school’s primary academic officer, coordinating all academic and curricular matters and overseeing student disciplinary actions. The role includes responsibility for the integrity of our academic programs, and its ongoing management, delivery, and assessment. I serve as a key advisor to the Dean on the administration of the law school, develop and manage our course schedules, hire and manage all adjunct and visiting instructors, assess and implement new curricular offerings like our Concentrations (adding a new Race, Equity, & the Law Concentration in 2020). I am the Director of Penn State Law’s Joint Degree programs. I also teach Professional Responsibility, and Intersectionality & the Law. Prior to my associate deanship, I directed our Family Law Clinic, which I opened in January 2010. I managed the Clinic’s Supervising Attorney and our students, who work on domestic violence and other family cases in the local courts. I developed and taught the Clinic seminar, and I previously taught Family Law, and Externships. I extensively redesigned our Externships curriculum, adding an “Externships Everywhere” course, paid externships, and remote externships. For five years I directed our Public Interest programs; and I helped launch our Mindfulness in Law Society in 2018 and our George Floyd Memorial Scholarship in 2020. OTHER TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATIONS: Adjunct Faculty, Media Law, 2002-2004. -

20026 Alaska Native Medical Center

Preliminary Preliminary Medicare ID Hospital Street City State Zip County Penalty HAC Score 20026 Alaska Native Medical Center 4315 Diplomacy Dr Anchorage AK 99508 Anchorage Y 9 20017 Alaska Regional Hospital 2801 Debarr Road Anchorage AK 99508 Anchorage Y 8.95 20008 Bartlett Regional Hospital 3260 Hospital Dr Juneau AK 99801 Juneau N 3 20024 Central Peninsula General Hospital 250 Hospital Place Soldotna AK 99669 Kenai PeninsulaN 4 20012 Fairbanks Memorial Hospital 1650 Cowles Street Fairbanks AK 99701 Fairbanks NorthY Star 9 20006 Mat-Su Regional Medical Center 2500 South Woodworth LoopPalmer AK 99645 Matanuska NSusitna 6.75 20027 Mt Edgecumbe Hospital 222 Tongass Dr Sitka AK 99835 Sitka N 7 20001 Providence Alaska Medical Center Box 196604 Anchorage AK 99519 Anchorage Y 8.05 20018 Yukon Kuskokwim Delta Reg HospitalPo Box 287 Bethel AK 99559 Bethel N 6 10036 Andalusia Regional Hospital 849 South Three Notch StreetAndalusia AL 36420 Covington N 6 10079 Athens-Limestone Hospital 700 West Market Street Athens AL 35611 Limestone N 5.6 10169 Atmore Community Hospital 401 Medical Park Drive Atmore AL 36502 Escambia N 7 10149 Baptist Medical Center East 400 Taylor Road Montgomery AL 36117 MontgomeryN 3.6 10023 Baptist Medical Center South 2105 East South Boulevard Montgomery AL 36116 MontgomeryN 3.95 10103 Baptist Medical Center-Princeton 701 Princeton Avenue SouthwestBirmingham AL 35211 Jefferson N 5.45 10058 Bibb Medical Center 208 Pierson Ave Centreville AL 35042 Bibb N 7 10139 Brookwood Medical Center 2010 Brookwood Medical CenterBirmingham -

“I Love This Penn State – but Freedom Is Dearer to Me”

“I Love This Penn State – But Freedom Is Dearer To Me” H. Jesse Arnelle: “A Love-Wait Affair” – May 18, 1968 (Note: On May 18, 1968 H. Jesse Arnelle, the former Nittany Lion Basketball All-American, and Football All-American honorable mention, was the guest of honor at the Penn State Football Awards Banquet. Arnelle would stun many in the crowd by denouncing the University’s record in failing to recruit more Black students, faculty and staff, instead of talking about sports. He further shocked many by turning down the first Annual Alumni Award in protest. The following is a partial text of H. Jesse Arnelle’s speech delivered that evening as printed in the November 19, 1968 Daily Collegian.) These are very dissimilar times from the decade of the 1950s when I attended Penn State University. Rather than embroider further the “sweet smell of success,” which is the obvious theme of this evening’s occasion, I have had to reluctantly decide to go at variance with precedence. Forego the pleasure of polite banality and not give into what would be very heavy nostalgia, but use the time instead to speak of our monumental and historical failures; the things that bring dishonor instead of glory to the University; issues pivotal to our time, heavy on my conscience and lay uncomfortably on the hearts of most American. Since it has been over a decade when I was last amongst you… and since it may be another before I return, I ask that you indulge me a little longer than the twenty-five minutes allowed. -

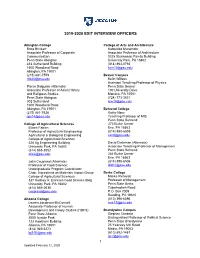

2019-2020 Exit Interview Officers 1

2019-2020 EXIT INTERVIEW OFFICERS Abington College College of Arts and Architecture Ross Brinkert Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Corporate Associate Professor of Architecture Communication 0325 Stuckeman Family Building Penn State Abington University Park, PA 16802 414 Sutherland Building (814) 863-0793 1600 Woodland Road [email protected] Abington, PA 19001 (215) 881-7579 Beaver Campus [email protected] Keith Willson Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics Pierce Salguero (Alternate) Penn State Beaver Associate Professor of Asian History 100 University Drive and Religious Studies Monaca, PA 15061 Penn State Abington (724) 773-3831 302 Sutherland [email protected] 1600 Woodland Road Abington, PA 19001 Behrend College (215) 881-7826 Kathy Noce [email protected] Teaching Professor of MIS Penn State Behrend College of Agricultural Sciences 273 Burke Center Eileen Fabian Erie, PA 16563 Professor of Agricultural Engineering (814) 898-6508 Agricultural & Biological Engineering [email protected] College of Agricultural Sciences 228 Ag Engineering Building David Dieteman (Alternate) University Park, PA 16802 Associate Teaching Professor of Management (814) 865-3552 Penn State Behrend [email protected] 264 Burke Center Erie, PA 16563 John Coupland (Alternate) (814) 898-6506 Professor of Food Science; [email protected] Undergraduate Program Coordinator Chair, Ingredients as Materials Impact Group Berks College College of Agricultural Sciences Malika Richards 337 Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Bldg Professor of Management University Park, PA 16802 Penn State Berks