More Rivers to Cross Report Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divulgação Bibliográfica

Divulgação bibliográfica Julho/Agosto 2019 Biblioteca da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra Sumário BASES DE DADOS NA FDUC ........................................................................................ 4 E-BOOKS .................................................................................................................. 6 MONOGRAFIAS ........................................................................................................ 52 Ciências Jurídico-Empresariais................................................................................................................. 53 Ciências Jurídico-Civilísticas ..................................................................................................................... 70 Ciências Jurídico-Criminais ...................................................................................................................... 79 Ciências Jurídico-Económicas .................................................................................................................. 82 Ciências Jurídico-Filosóficas ..................................................................................................................... 83 Ciências Jurídico-Históricas ..................................................................................................................... 88 Ciências Jurídico-Políticas ........................................................................................................................ 94 Vária ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability

Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability Jasmin Kientzel Boekenplan ISBN 978 90 8666 377 4 Copyright © 2015 Jasmin Kientzel Published by Boekenplan, Maastricht, the Netherlands Determinants of Professional Commitment to Environmental Sustainability Dissertation to obtain the degree of Doctor at Maastricht University, on the authority of the Rector Magnificus, Prof. dr. L.L.G. Soete, in accordance with the decision of the Board of Deans, to be defended in public on Wednesday 9 September 2015, at 16:00 hours By Jasmin Kientzel Promotor Prof. Dr. Gerjo Kok Co-supervisor Dr. Mindel van de Laar Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Harm Hospers (Chair) Prof. Dr. Piet Eichholtz Prof. Dr. Rob Ruiter Dr. Ruud Jonkers, Retired director of ResCon bv. iv Acknowledgments “Even if we could turn back, we’dprobably never end up where we started”. (Haruki Murakami, 1Q84) Drafting this dissertation has been a journey of discovery, and it would be almost impossible to list all the milestones, lessons learned and limits encountered on the way. Just as everyone who embarks on a long journey into the wild, the experience itself has afforded me a wealth of knowledge about the world around me and my role in it and more than I had thought previously possible. The biggest revelation was that no stage of this journey would have been possible without the many people whose support ensured my continuing even when I seemed to have hit a roadblock: Without their encouragements and understanding I would not be writing this acknowledgment. I would like to express my special appreciations and thanks to my two supervisors, Professor Dr. -

Sept. 10-12, 2018

Vol. 119, No. 7 Sept. 10-12, 2018 REFLECTIONS Seventeen years after the attacks on 9/11 — Shanksville remembers By Tina Locurto that day, but incredible good came out in response,” Barnett said THE DAILY COLLEGIAN with a smile. Shanksville is a small, rural town settled in southwestern Heroes in flight Pennsylvania with a population of about 237 people. It has a general Les Orlidge was born and raised in Shanksville. But, his own store, a few churches, a volunteer fire department and a school dis- memories of Sept. 11 were forged from over 290 miles away. trict. American flags gently hang from porch to porch along streets A Penn State alumnus who graduated in 1977, Orlidge had a short with cracked pavement. stint with AlliedSignal in Teterboro, New Jersey. From the second It’s a quiet, sleepy town. floor of his company’s building, he witnessed the World Trade Cen- It’s also the site of a plane crash that killed 40 passengers and ter collapse. crew members — part of what would become the deadliest attack “I watched the tower collapse — I watched the plane hit the on U.S. soil. second tower from that window,” Orlidge said. “I was actually de- The flight, which hit the earth at 563 mph at a 40 degree angle, left pressed for about a year.” a crater 30-feet wide and 15-feet deep in a field in the small town of Using a tiny AM radio to listen for news updates, he heard a re- Shanksville. port from Pittsburgh that a plane had crashed six miles away from Most people have a memory of where they were during the at- Somerset Airport. -

Two Talented Qbs, No Controversy Matt Lingerman the Daily Collegian

Follow us on Vol. 119, No. 21 Oct. 29-31, 2018 Race for 34th District ‘uniquely tied’ to student debt By Patrick Newkumet nity to use the Senator’s tenure against er Murphy, said in a statement. “That ‘DEBT’ THE DAILY COLLEGIAN him. can come in the form of direct support “Unfortunately, Pennsylvania has the to public colleges and universities or in State Sen. Jake Corman and Ezra highest average level of student debt for the form of grants to students that have Nanes — opponents in Pennsylvania’s higher education in the entire nation,” demonstrated socio-economic need.” 34th district race — have battled over Nanes said. “Senator Corman, that has Murphy said Nanes “is committed to student debt as the two seek to repre- happened on your watch.” ensuring that oil and natural gas com- sent a constituency deeply tied to Penn Pennsylvania actually has the sec- panies pay their fair share so we have State. ond-highest student debt in the country, money to invest in public education.” Corman has held the seat since 1999, as Forbes estimates the average stu- In his issue statements, it is unclear OUT but it has been in the family much lon- dent accrues $35,759 in loans for higher to what extent Nanes plans on expand- ger. His father, former Sen. Jacob Cor- education. ing the funding of public education. man Jr., took control of the 34th District This can be for any number of factors. An overhaul of the entire system is on June 7, 1977, where he served for The conglomeration of private and unlikely, should he win, as the Penn- over 20 years before being succeeded public universities within each sylvania State Senate is strongly by his son. -

Print Version (Pdf)

Special Collections and University Archives UMass Amherst Libraries UMass Student Publications Collection 1871-2011 27 boxes (16.5 linear foot) Call no.: RG 045/00 About SCUA SCUA home Credo digital Scope Inventory Humor magazines Literary magazines Newspapers and newsletters Yearbooks Other student publications Admin info Download xml version print version (pdf) Read collection overview Since almost the time of first arrival of students at Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1867, the college's students have taken an active role in publishing items for their own consumption. Beginning with the appearance of the first yearbook, put together by the pioneer class during their junior year in 1870 and followed by publication of the first, short-lived newspaper, The College Monthly in 1887, students have been responsible for dozens of publications from literature to humor to a range of politically- and socially-oriented periodicals. This series consists of the collected student publications from Massachusetts Agricultural College (1867-1931), Massachusetts State College (1931-1947), and the University of Massachusetts (1947-2007), including student newspapers, magazines, newsletters, inserts, yearbooks, and songbooks. Publications range from official publications emanating from the student body to unofficial works by student interest groups or academic departments. Links to digitized versions of the periodicals are supplied when available. See similar SCUA collections: Literature and language Mass Agricultural College (1863-1931) Mass State College (1931-1947) UMass (1947- ) UMass students Background Since almost the time of first arrival of students at Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1867, the college's students have taken an active role in publishing items for their own consumption. -

Future Mrs. Collegian Graphics by Kaylyn Mcgrory Page 2 | Feb

Independently published by students at penn state Dailu Collegian Vol. 119, No. 40 Feb. 7-10, 2019 collegian.psu.edu The Issue, with love With about a week until Valentine’s Day, why not donate an entire edition to the different loves in college life — from significant others to students’ relationship with sleep. But what’s the point of Valentine’s Day? No one really knows. Future Mrs. Collegian Graphics by Kaylyn McGrory PAGE 2 | FEB. 7-10, 2019 LOVE EDITION THE DAILY COLLEGIAN Tips and activities for ‘Galentine’s Day’ Natalie Schield can cost less than $10. chocolate syrup. Don’t forget Wine not? each other and take the sketch to THE DAILY COLLEGIAN Pick up some fresh strawber- your Polaroid camera, because it For a simple DIY project that a local tattoo artist. This personal ries from the grocery store and a will be a brunch you won’t want to requires little to no artistic skills, design will show the connection This Valentine’s Day, ditch the packet of Nestle chocolate chips. forget. try out this affordable task. Take you and your BFF have. most common date night ideas Decorate these cute treats with a trip to either Michael’s or Although the price range for and spend some time with your Valentine’s Day sprinkles or Spa day Hobby Lobby with your BFF and tattoos is unpredictable going in, BFF instead. Try something you some shredded coconut. Be sure you won’t regret it. The bonding Face masks, lip scrub and ped- pick up a variety of acrylic paints have never thought of doing. -

Lutie Lytle 2019 Program

PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 1 13th Annual LUTIE A. LYTLE Black Women Law Faculty Workshop & Writing Retreat June 19-26, 2019 | University Park, PA 2 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT Claiming the Power of our Sisterhood 2019 Lutie Lytle Workshop and Retreat hosted on the campus of Penn State Law in the Lewis Katz Building, University Park, PA. Illustration credit: Mary Szmolko Cover photos credit: Penn State PENN STATE LAW | UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 13TH ANNUAL LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP AND WRITING RETREAT Hosted by: Penn State Law June 19-26, 2019 Welcome 4 Sponsors 6 About Our Honoree - 2019 Lutie A. Lytle Outstanding Scholar Award 7 About the Guest Speakers 8 Workshop & Writing Retreat Schedule 10 Participants 19 Committee Members 27 4 2019 LUTIE A. LYTLE BLACK WOMEN LAW FACULTY WORKSHOP & WRITING RETREAT WELCOME FROM THE DEAN The Lutie Lytle Conference was mentoring and support for founded after a small number of scholarship, teaching, and service black women faculty, organized by for Lutie participants. I am so Professor Imani Perry, grateful that Professor Brown is collaborated at the Chicago home a part of the Penn State Law and of Professor Michele Goodwin. The School of International Affairs first official conference was held community. In addition to her at the University of Iowa College many contributions to the two of Law and was organized by then schools, the Rock Ethics Institute, Professor and now Dean Angela and the broader Penn State Onwauchi-Willig. The vision of community, she has done an the original collaboration and the outstanding job fundraising and first conference continue to guide organizing this event. -

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 8

Jill Callahan Engle: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Professor of Clinical Law Penn State Law- University Park, PA Phone: 814-865-5047 | Email: [email protected] | Twitter: @jillengle LEGAL TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE LAW: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Prof. of Clinical Law, 2007-present Reporting directly to the Dean, I am the law school’s primary academic officer, coordinating all academic and curricular matters and overseeing student disciplinary actions. The role includes responsibility for the integrity of our academic programs, and its ongoing management, delivery, and assessment. I serve as a key advisor to the Dean on the administration of the law school, develop and manage our course schedules, hire and manage all adjunct and visiting instructors, assess and implement new curricular offerings like our Concentrations (adding a new Race, Equity, & the Law Concentration in 2020). I am the Director of Penn State Law’s Joint Degree programs. I also teach Professional Responsibility, and Intersectionality & the Law. Prior to my associate deanship, I directed our Family Law Clinic, which I opened in January 2010. I managed the Clinic’s Supervising Attorney and our students, who work on domestic violence and other family cases in the local courts. I developed and taught the Clinic seminar, and I previously taught Family Law, and Externships. I extensively redesigned our Externships curriculum, adding an “Externships Everywhere” course, paid externships, and remote externships. For five years I directed our Public Interest programs; and I helped launch our Mindfulness in Law Society in 2018 and our George Floyd Memorial Scholarship in 2020. OTHER TEACHING EXPERIENCE: PENN STATE COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATIONS: Adjunct Faculty, Media Law, 2002-2004. -

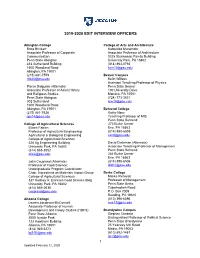

2019-2020 Exit Interview Officers 1

2019-2020 EXIT INTERVIEW OFFICERS Abington College College of Arts and Architecture Ross Brinkert Katsuhiko Muramoto Associate Professor of Corporate Associate Professor of Architecture Communication 0325 Stuckeman Family Building Penn State Abington University Park, PA 16802 414 Sutherland Building (814) 863-0793 1600 Woodland Road [email protected] Abington, PA 19001 (215) 881-7579 Beaver Campus [email protected] Keith Willson Assistant Teaching Professor of Physics Pierce Salguero (Alternate) Penn State Beaver Associate Professor of Asian History 100 University Drive and Religious Studies Monaca, PA 15061 Penn State Abington (724) 773-3831 302 Sutherland [email protected] 1600 Woodland Road Abington, PA 19001 Behrend College (215) 881-7826 Kathy Noce [email protected] Teaching Professor of MIS Penn State Behrend College of Agricultural Sciences 273 Burke Center Eileen Fabian Erie, PA 16563 Professor of Agricultural Engineering (814) 898-6508 Agricultural & Biological Engineering [email protected] College of Agricultural Sciences 228 Ag Engineering Building David Dieteman (Alternate) University Park, PA 16802 Associate Teaching Professor of Management (814) 865-3552 Penn State Behrend [email protected] 264 Burke Center Erie, PA 16563 John Coupland (Alternate) (814) 898-6506 Professor of Food Science; [email protected] Undergraduate Program Coordinator Chair, Ingredients as Materials Impact Group Berks College College of Agricultural Sciences Malika Richards 337 Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Bldg Professor of Management University Park, PA 16802 Penn State Berks -

Penn State University Public School Code of 1949 Volume 1

Public School Code of 1949 Volume I Compiled by: University Budget Office 308 Old Main University Park, PA 16802 December 2017 Table of Contents Volume I Introduction .................................................................... Tab A Summary Schedules ....................................................... Tab B Operating Budget – 2017-18........................................... Tab C Employee Headcounts and Salary Data .......................... Tab D Non-Salary Compensation .............................................. Tab E University Retirement Policies ........................................ Tab F Tuition Grant-in-Aid ....................................................... Tab G 2016-17 Travel Expenditures.......................................... Tab H Volume II Actual Operating Expenditures - 2016-17 Volume III Goods and Services Expenditures J:\STAIRS\STAIRS 2017\STAIRS VOL. 1 TOC.DOCX 11/21/17 TAB A Introduction THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY Public School Code of 1949 December 2017 Public School Code of 1949, requires that Penn State submit a report within 180 days of the close of the university’s current fiscal year. The 2016-17 fiscal year closed on June 30, 2017. Therefore, this report is submitted in compliance with the above mentioned House Bill, which specified that the University provide the following: (A1) Revenue and expenditure budgets of the university’s academic and administrative support units for the current fiscal year. (A2) The actual revenue and expenditures for the prior year in the same format as the information reported above. (A3) For any defined project or program which is the subject of a specific line item appropriation from the General Fund, the university shall disclose the following: (A3i) Revenue and expenditure budgets of the defined program or project for the current fiscal year. (A3ii) The actual revenue and expenditures of the defined program or project for the prior year in the same format as the information reported under paragraph a1. -

Thedickinson

38644out 4/1/10 2:45 PM Page 1 The Dickinson Lawyer The Dickinson School of Law Celebrating 175 Years of Excellence Penn State UniverSity DickinSon School of law alUmni magazine — winter 2010 38644out 4/1/10 2:25 PM Page 2 A L ETTER FROM THE DEAN An anniversary event is as much a time to look to the future as it is to celebrate the past. A special pull-out section of this issue of The Dickinson Lawyer features a 175-year timeline with milestones that reflect how The Dickinson School of Law has helped shape our region, our country, and our world. The section ends with a photo “walk through” of our new and renovated facilities in Carlisle which will be dedicated on April 16. Together with our award-winning Lewis Katz Building at University Park, our new facilities provide our students with several unique advantages. In our courtroom, for example, students were recently able to observe Judge D. Brooks Smith ’76 as part of a Third Circuit panel hearing a last-minute death penalty appeal. In our classrooms, students compare con - stitutional issues with their peers in South Africa and Australia. In our library, students have 24/7 access to a vast collection of resources that puts answers at their fingertips. We’re also celebrating the 30-year anniversary of our clinical program, which began in earnest with our Family, Disability and Arts, Sports and Entertainment Law clinics. In 2008, we expanded our clinics to include opportunities for students to work on immigration and civil rights issues on a national level. -

Of the Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity March

fHE AND OF THE PI KAPPA ALPHA FRATERNITY MARCH. 1950 IIKA -INITIATES! NOW YOU CAN WEAR A III{ A BADGE ORDER IT TODAY FROM THIS OFFICIAL PRICE LIST- SisLer P in ~lin ia- o r PLA l i\' 1u rc No. 0 No. I N o.2 No. 3 Bevel llorder 3.50 5.25 6.25 6.75 9.00 N ugget. Chased or E ngraved Bo rder 4.00 5.75 6.75 7.25 10.50 FULL CROWN SET J EW ELS No. 0 No. I No.2 No. 2'h No.3 Pearl Border ...... ~ 13.00 15.00 . 17.50 21.00 24.00 Pearl Uo rder, Ruby or apphire Poin ts .......... ~-------~------~--~--~- 14.00 16.25 19.00 23.00 26.00 Pearl Border, Emerald Points .... 16.00 18.00 2 1.50 26.00 30.00 Pearl Border, D ia mo nd Po ints ... 36.00 4 1. 00 5 1.50 63.00 80.00 Pearl and Sapp hire Alternating ------~~- ~~ ........... 15.00 17.50 20.75 25 .00 28.00 Pearl and Ruby Alternating --~--- 15.00 17.50 20.75 25.00 28.00 Pearl and Emerald Alternating .. 19. 00 21. 00 25.50 31. 00 36.00 Pearl and Diamond Alternating -~ .......... ~ ......... -~~ _ 59.00 67.00 85.50 I 05.00 136.00 Diamo nd and Ruby or Sap p h ire Alternating ~ ...... ~-~-~ .................. 61. 00 69.50 88.75 109.00 140.00 Diamo nd and E merald Alternating ..... _ .......... -~~~~~----- 65.00 73.00 93.50 115.00 148.00 Ruby or Sap p hire B o rd e r -~~-~----- 17.00 19.75 24.00 29.00 32.00 Ruby or Sa pphire Bo rder, D iamond Po ints -------·-- ~-~~~----~ 39.00 44.75 56.50 69.00 86.00 Diamond Bo rder .....