George Streeter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA Jforr/STOWM

BULLETIN jo/^fAe> HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA JfORR/STOWM Somery PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AT IT5 ROOM5 18 EAST PENN STREET NORR15TOWN.PA. APRIL, 1952 VOLUME VIII NUMBER 2 PRICE ONE DOLLAR Historical Society of Montgomery County OFFICERS Donald A. Gallager, Esq., President George K. Brbcht, Esq., First Vice-President Foster C. Hillegass, Second Vice-President David E. Groshens, Esq., Third Vice-president Eva G. Davis, Recording Secretary Helen E. Richards, Corresponding Secretary Mrs. LeRoy Burris, Financial Secretary Lyman a. Kratz, Treasurer Mrs. LeRoy Burris, Librarian TRUSTEES Kirke Bryan, Esq. Mrs. H. H. Francine Donald A. Gallager, Esq. Herbert H. Ganser Nancy P. Highley Foster G. Hillegass Mrs. a. Conrad Jones Hon. Harold G. Knight Lyman A. Kratz Douglas Macfarlan, M.D. Katharine Preston Frankun a. Stickler Mrs. James I. Wendell Mrs. Franklin B. Wildman, Jr. Norris D. Wright Photo by Wm. M. Rittase, Phila. Chapel at The Hill School, Pottstown, Pa. THE BULLETIN of the Historical Society of Montgomery County Published Semi-Anrmally — October and April Volume VIII April, 1952 Number 2 CONTENTS The Hill School Dr. James I. Wendell 67 Early History of Lower Pottsgrove Township Rev. Carl T. Smith 86 Henry S. Landes Jane Keplinger Burris 96 Deaths in the Skippack Region. ..Hannah Benner Roach 98 Early Land Transactions of Montgomery County Charles R. Barker 115 Neighborhood News and Notices Compiled 128 First Sunday School in Norristown. Rudolf P. Hommel 141 Reports 145 Publication Committee Mrs. LeRoy Bubbis Jean E. Gottshall Charles R. Barker, Chairman 65 The Hill School* Dr. James I. Wendell, Head Master Mr. -

Introduction to the Sixteenth C.U. Arie¨Ns Kappers Lecture

Progress in Brain Research, Vol. 147 ISSN 0079-6123 Copyright ß 2005 Elsevier BV. All rights reserved CHAPTER 4 Introduction to the sixteenth C.U. Arie¨ns Kappers lecture D.F. Swaab*, J. van Pelt and M.A. Hofman Netherlands Institute for Brain Research, Meibergdreef 33, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands Professor Dennis D.M. O’Leary was invited to Royal Society, the ‘‘Central Commission for Brain deliver the sixteenth C.U. Arie¨ns Kappers Lecture Research’’ was constituted. This so-called ‘‘Brain during the 23rd International Summer School of Commission’’ set itself the task of ‘‘... organizing a Brain Research on 25 August 2003, for his out- network of institutions throughout the civilized world, standing achievements in unraveling the molecular dedicated to the study of the structure and functions control of cortical development. The C.U. Arie¨ns of the central organ....’’ Several governments respon- Kappers Award was created to honor the first ded to this ambition by founding brain research director of the Netherlands Institute for Brain institutes (Table 2), among which was the Central Research. The award is presented approximately Institute for Brain Research in the Netherlands, which once a year to a leading and outstanding neuroscien- opened its doors on 8 June 1909, in the presence of the tist, who is invited to give the C.U. Arie¨ns Kappers Nobel laureate Dr. Camillo Golgi. Lecture (Table 1). Prof. C.U. Arie¨ns Kappers became the first Cornelius Ubbo Arie¨ns Kappers was born in director of the institute, a position he held until his Groningen in 1877. -

Franz Nissl (1860-1919), Noted Neuropsychiatrist and Neuropathologist, Staining the Neuron, but Not Limiting It

Dement Neuropsychol 2019 September;13(3):352-355 History Note http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642018dn13-030014 Franz Nissl (1860-1919), noted neuropsychiatrist and neuropathologist, staining the neuron, but not limiting it Marleide da Mota Gomes1 ABSTRACT. Franz Alexander Nissl carried out studies on mental and nervous disorders, as a clinician, but mainly as a pathologist, probably the most important of his time. He recognized changes in glial cells, blood elements, blood vessels and brain tissue in general, achieving this by using a special blue stain he himself developed – Nissl staining, while still a medical student. However, he did not accept the neuron theory supported by the new staining methods developed by Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Nissl had worked with the crème de la crème of German neuropsychiatry, including Alois Alzheimer, besides Emil Kraepelin, Korbinian Brodmann and Walther Spielmeyer. He became (1904), Kraepelin’s successor as Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Psychiatric Clinic, in Heidelberg. Moreover, in 1918, the year before Nissl´s death, Kraepelin offered him a research position as head of the Histopathology Department of the newly founded “Deutsche Forschungsanstalt fur Psychiatrie” of the Max Planck Institute for Psychiatry, in Munich. Key words: Franz Nissl, neuropathology, staining method, neuron theory. FRANZ NISSL (1860-1919), NOTÁVEL NEUROPSIQUIATRA E NEUROPATOLOGISTA, TINGINDO O NEURÔNIO, MAS NÃO O LIMITANDO RESUMO. Franz Alexander Nissl realizou estudos sobre transtornos mentais e nervosos, como clínico, mas principalmente como patologista, provavelmente o mais importante de seu tempo. Ele reconheceu mudanças nas células gliais, elementos sangüíneos, vasos sangüíneos e tecido cerebral em geral, realizando-o por meio de um corante azul especial desenvolvida por ele mesmo – coloração de Nissl, ainda como estudante de medicina. -

The Neuro Nobels

NEURO NOBELS Richard J. Barohn, MD Gertrude and Dewey Ziegler Professor of Neurology University Distinguished Professor Vice Chancellor for Research President Research Institute Research & Discovery Director, Frontiers: The University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Grand Rounds Institute February 14, 2018 1 Alfred Nobel 1833-1896 • Born Stockholm, Sweden • Father involved in machine tools and explosives • Family moved to St. Petersburg when Alfred was young • Father worked on armaments for Russians in the Crimean War… successful business/ naval mines (Also steam engines and eventually oil).. made and lost fortunes • Alfred and brothers educated by private teachers; never attended university or got a degree • Sent to Sweden, Germany, France and USA to study chemical engineering • In Paris met the inventor of nitroglycerin Ascanio Sobrero • 1863- Moved back to Stockholm and worked on nitro but too dangerous.. brother killed in an explosion • To make it safer to use he experimented with different additives and mixed nitro with kieselguhr, turning liquid into paste which could be shaped into rods that could be inserted into drilling holes • 1867- Patented this under name of DYNAMITE • Also invented the blasting cap detonator • These inventions and advances in drilling changed construction • 1875-Invented gelignite, more stable than dynamite and in 1887, ballistics, predecessor of cordite • Overall had over 350 patents 2 Alfred Nobel 1833-1896 The Merchant of Death • Traveled much of his business life, companies throughout Europe and America • Called " Europe's Richest Vagabond" • Solitary man / depressive / never married but had several love relationships • No children • This prompted him to rethink how he would be • Wrote poetry in English, was considered remembered scandalous/blasphemous. -

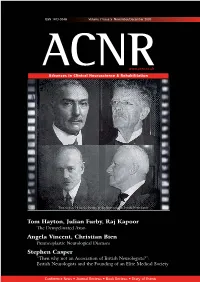

ACNRND07:Layout 1

ISSN 1473-9348 Volume 7 Issue 5 November/December 2007 ACNRwww.acnr.co.uk Advances in Clinical Neuroscience & Rehabilitation Turn to page 16 for the history of the Association of British Neurologists Tom Hayton, Julian Furby, Raj Kapoor The Demyelinated Axon Angela Vincent, Christian Bien Paraneoplastic Neurological Diseases Stephen Casper “Then why not an Association of British Neurologists?”: British Neurologists and the Founding of an Elite Medical Society Conference News • Journal Reviews • Book Reviews • Diary of Events Pen & Pump Ad V2 210x297 4/9/07 12:12 Page 1 ON &ON&ON&ON &ON&ON&ON& APO-go: treatment for both PREDICTABLE and UNPREDICTABLE symptoms of Parkinson’s disease Predictable symptoms: Use APO-go Pen early in treatmenttreatment plan for rapid reversal of impending “off’s”. Simple, easy to use sc injection Positive NICE review: “Intermittent apomorphine injections may be used to reduce “off” time in people with PD with severe motor complications.” Unpredictable symptoms: Use continuous APO-go infusion for full waking-day cover. Continuous dopaminergic stimulation – reduces pulsatile treatment-related complications including “on-off” fl uctuations Positive NICE review: “Continuous subcutaneous infusions of apomorphine may be used to reduce “off” time and dyskinesia in people with PD with severe motor complications.” Make the switch and turn their “off’s” to “on” ABRIDGED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Patients must be informed of this and advised to exercise caution while Consult Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing. Uses The treatment of disabling motor driving or operating machines during treatment with apomorphine. Haematology tests should be undertaken fluctuations (‘’on-off’’ phenomena) in patients with Parkinson’s disease which persist despite individually titrated at regular intervals as with levodopa when given concomitantly with apomorphine. -

Official U.S. Bulletin

. PUBLISHED DMILY under order of THE PRESIDENT of THE UNITED STJITES by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL. Chairman -k -k -k COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activltiea '' VOL. 3 WASHINGTO>f, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY G, 1919. No. 531 WILL RELEASE CHARTERED Archangel Medical Corps RESIGNATION OF MEMBERS KCRWEGIAN, SWEDISH, AND Giving Excellent Service OF PRICE-FIXING COMMITTEE > To the American Troops : DANiSHSHlPS,EXCEPTTHOSE ACCEPTED BY PRESIDENT British Officer Reports L NEEDED FOR CERTAIN USES TO TAKE EFFECT MARCH 1 The War Department au- thorizes the pul)lication of the AVAILABLE TO OWNERS following cablegram from the APPRECIATION OF TBEIR . AT END OF VOYAGES commantling general, Archangel, SERVICES EXPRESSED to the British War Office: Shipping Board Announces “ I have made a jiersonal in- Request for Final Release its Readiness to Give Up spection of all the hospitals and from Its Duties on March dressing stations in this coun- Vessels, Except Those Re- First and Appreciation of j try; and I find that the medical quired for Relief Purposes arrangements are first class. Confidence Shown by Mr, i or Use of Governments Among the American troops Wilson in the Committee ; there less than per cent in are Correspond* Associated With United hospitals from all causes, show- Contained in States in the War, ing that the health of the troops ence Made Public Here. is good. In this climate, the The Shippins Bosinl announces that evacuation of casualties over The following correspondence has been duo to the cliansctl conditions resultiu!' made pnhiic: 120 miles of road by sledge has ; from the cessation of hostilities the Gov- AitEurcAN Commission ernmeijts of Norway, been carried out efficiently and ; Sweden, and Den- TO Negotiate Peace. -

The Study of Primate Brain Evolution: Where Do We Go from Here?

Page 1 Jerison (2001 draft of Festschrift Epilogue [Comments for 2007 pdf in square brackets] The Study of Primate Brain Evolution: Where Do We Go From Here? Harry J. Jerison I am pleased to accept the title that Dean Falk and Kathleen Gibson assigned me for this concluding essay. And of course I thank them for arranging the meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in my honor. Most of all I must thank the contributors at that meeting and the others who have taken time to prepare the chapters in this book, which commemorates that meeting. In my judgment it would be inappropriate for me to comment on those excellent chapters, to argue with some of them or to agree with others. The chapters speak well for themselves, I will leave commentary to the journals, such as Current Anthropology or Brain and Behavior Sciences, that specialize in it. It has been a great pleasure to be involved with these activities. I will depart from my assignment in three ways. First I must write about where I would go from here rather than prescribe for others. The chapters in this book present better prescriptions than I am competent to offer for the route our field as a whole can take. Second, I would like to write about where we have been, because my particular route is so much one involving the fossil evidence that I think it takes some explaining. Finally, I have to write about more than only primates, because my emphasis has been and continues to be on the evolution of the vertebrate brain, including the primates among the mammals. -

Tilly Edinger and the Science of Paleoneurology

Brain Research Bulletin, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 351–361, 1999 Copyright © 1999 Elsevier Science Inc. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0361-9230/99/$–see front matter PII S0361-9230(98)00174-9 HISTORY OF NEUROSCIENCE The gospel of the fossil brain: Tilly Edinger and the science of paleoneurology Emily A. Buchholtz1* and Ernst-August Seyfarth2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, USA; and 2Zoologisches Institut, Biologie-Campus, J.W. Goethe-Universita¨ t, D-60054 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [Received 21 September 1998; Revised 26 November 1998; Accepted 3 December 1998] ABSTRACT: Tilly Edinger (1897–1967) was a vertebrate paleon- collection and description of accidental finds of natural brain casts, tologist interested in the evolution of the central nervous that is, the fossilized sediments filling the endocrania (and spinal system. By combining methods and insights gained from com- canals) of extinct animals. These can reflect characteristic features parative neuroanatomy and paleontology, she almost single- of external brain anatomy in great detail. handedly founded modern paleoneurology in the 1920s while Modern paleoneurology was founded almost single-handedly working at the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt am Main. Edinger’s early research was mostly descriptive and conducted by Ottilie (“Tilly”) Edinger in Germany in the 1920s. She was one within the theoretical framework of brain evolution formulated of the first to systematically investigate, compare, and summarize by O. C. Marsh in the late 19th -

World War I and the Art of War: WWI Posters from the Collection of Oscar Jacobson OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT

World War I and The Art of War: WWI Posters from the Collection of Oscar Jacobson OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT The beginnings of World War I (WWI) in Europe began long before the United States joined the Great War. In June of 1914, the Archduke of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassi- nated. The Austrians suspected the Serbians, and declared war one month later. The chain reaction after these events are what would become the Great War, or the First World War. The United States did not formally enter the war until it declared war on Germany in 1917. The war had many effects on the United States and Oklahomans before entrance into war in 1917. There were supporters and opponents of the war, opponents of the Selective Service Act, and effects on the United States' economy. Crop prices fell and rose, rations began to conserve for the war, and free speech was ques- tioned. Many of these issues lasted throughout the war. Explore the Great War and its lasting effects on Oklahoma throughout this exhibit. Dan Smith (1865–1934), Put Fighting Blood in Your Business.1 American Red Cross Blood Drive (OHS Collections).1 World War 1 and the Art of War | 2017 │1 World War I and The Art of War Timeline 1914 June 1914 – Franz Ferdinand, archduke of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie are assassinated July 1914 – Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia August 1914 – Germany declares war on Russia, France, Belgium, and in- vades France Britain declares war on Germany and Austria-Hungary US declares -

STAHNISCH Frank W – CV May 31, 2020 the University of Calgary Faculty of Arts / Cumming School of Medicine CURRICULUM VITAE

STAHNISCH Frank W – CV May 31, 2020 The University of Calgary Faculty of Arts / Cumming School of Medicine CURRICULUM VITAE I. BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Prof. Frank W. Stahnisch University of Calgary Teaching, Research and Wellness Building Room 3E41 3280 Hospital Drive NW Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 4Z6 Telephone: 403-210-6290 Fax: 403-270-7307 Email: [email protected] https://hom.ucalgary.ca http://ucalgary.ca/communityhealthsciences Present Rank: Full Professor (“tenured”) Additional Alberta Medical Foundation/Hannah Professorship Affiliation: in the History of Medicine and Health Care Department: History Faculty: Arts & Department: Community Health Sciences Faculty: Cumming School of Medicine Supervisory PhD and MA, Faculty of Arts* Privileges: PhD and MSc, Cumming School of Medicine* **Dean’s Renewal for next Five-Year Term (2019-24) Institution: The University of Calgary II. ACADEMIC RECORD 1. Vordiplom (equivalent to a B.A., Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main), Germany, 1992 2. Physicum (equivalent to a B.Sc., Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main), Germany, 1993 3. Graduation as Master of Science (M. Sc.) in Philosophy of Science, University of Edinburgh (with distinction), United Kingdom, 1995 4. Medizinisches Staatsexamen (equivalent to an MD), Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany, 1998 May 31, 2020 1 STAHNISCH Frank W – CV 5. Medical Licence to Practice (Approbation), Department of Health, Berlin, Germany, 2000 6. Graduation as Doctor medicinae (Dr. med. – equivalent to a PhD) in History of Medicine, Free University of Berlin (magna cum laude), Germany, 2001 III. AWARDS AND DISTINCTIONS 03/2020 INVITED Endowed Lecture: Sebastian K. Littmann Keynote Lecture to the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Calgary Cumming School of Medicine, Foothills Medical Centre Auditorium, Calgary, Alberta (Canada). -

Ludwig Edinger.~) (1855---1918.) Von Kurt Goldstein

Ludwig Edinger.~) (1855---1918.) Von Kurt Goldstein. (Eingegangen am 15. Juli 1918.) M.H. So sehr es mir aueh nur mit den Gefiihlen des Schmerzes mSglich ist, fiber meinen verstorbenen Lehrer zu Ihnen zu sprechen, so sehr erscheint es mir andrerseits eine besonders ehrenvolle Aufgabe im ~rztlichen Verein einen Uberblick fiber das Lebenswerk Ludwig Edingers zu geben -- yon der Stelle aus, vonder der Verstorbene so viele seiner neuen Entdeckungen zuerst mitgeteilt hat. Eine ehren- volle Aufgabe, aber keine leiehte -- gilt es doch eine schier unfiberseh- bare Menge von Einzeluntersucl~ungen, von Ideen, deren Problematik noch gar nieht zu fibersehen, geschweige denn zu erschSpfen ist, die sich alle an den Namen Edinger knfipfen, in einen einheitlichen Rah- men zusammenzubringen. Wenn mir dies doch gelingen sollte, so liegt dies an dem einheitliehen Grundzug, der, wie wir spater sehen wer- den, alle die Arbeiten und Gedanken Edingers durchzieht. Der Lebensgang Ludwig Edingers ist schnell geschildert. Er ist 1855 in Worms geboren, studierte in Heidelberg und Stra[tburg. Unter dem Einflui] so ausgezeiehneter Lehrer wie Gegenbaur und Waldeyer erwachte frfihzeitig sein Interesse ffir die Anatomie und Biologie. So entstanden seine ersten wissensehaftlichen Arbeiten: die Dissertation ,,Uber die Schleimhaut des Fisehdarmes (usw.)" 18761), die ,,Untersuehung fiber die Endigung der Haut- nerven bei Pterotrachea ''2) und ,,Uber die Drfisenzellen des Magens besonders beim Menschen"3). Naeh Beeudigung seiner Stuclienzeit land E d i n g e r nieht die seinen Neigungen zur vergleichenden Anatomie und Biologie entspreehende Assistentenstelle; er mul~te eine klinisehe Stelle annehmen. Er be- schreibt in seinem Aufsatze zu Kussmauls 60. Geburtstage 121) sehr eindringlich seinen Schmerz darfiber; glaubte er doch, dadureh von seinem eigenttichen Berufe, dem des Anatomen und Biologen, abzu- *) Nach einem bei der Trauel~eicr fiir Ludwig Edinger im ~rztlichen Verein zu Frankfurt a. -

Ergab Sich Bald Ein Merkwürdiges Hindernis ... « Zur Aktualität Von Ludwig Edingers Neurowissenschaftlichem Projekt

Wissenschafts- und Universitätsgeschichte »... ergab sich bald ein merkwürdiges Hindernis ... « Zur Aktualität von Ludwig Edingers neurowissenschaftlichem Projekt udwig Edinger (1855–1918) Lgalt als »die größte Autorität der vergleichenden Neurologie« /1/. Un- ter Neurologie verstand man sei- nerzeit alle Fächer, die zur Lehre vom Nervensystem beitrugen. In die- sem Sinne konzipierte Edinger sein Neurologisches Institut als interdiszip- linäre Arbeitsstätte zur Erforschung des Nervensystems. Neuroanatomie und Neuropathologie erhielten hier 1907 jeweils eigene Abteilungen, Aquarien und Terrarien standen für tierpsychologische Beobachtungen zur Verfügung, und Edinger hatte als Leiter der ersten Frankfurter Po- liklinik für Nervenkranke das ganze Spektrum neurologischer Krank- heitsbilder vor Augen. 1910 grün- dete er überdies einen Psychologi- schen Verein, in dem Mediziner mit Zoologen und Psychologen zusam- menarbeiteten. Durch Interdisziplinarität eine ■1 Das von Lovis Brücke zwischen Hirnforschung Corinth (1858 – und Psychologie zu schlagen, war 1925) gefertigte das erklärte Ziel Edingers, und Ölgemälde Ludwig Edingers zeichnete sein Institut unter den (145 × 110 cm) »interakademischen Hirnforschungs- entstand 1909 instituten« aus, die sich nach der und gilt als eines Jahrhundertwende zur »Brain der bedeutendsten Commission« zusammengeschlos- Arztporträts des sen hatten. Der Erste Weltkrieg setz- 20. Jahrhunderts. te dieser internationalen Kooperati- Das Bild gehört heute zu den Be- on ein Ende, die erst in den 1960er ständen des His- Jahren als »Neuroscience« wieder torischen Muse- institutionelle Strukturen finden ums in Frankfurt sollte. Allerdings ist es bisher nicht am Main. gelungen, die konzeptionell unver- bundene Praxis der einzelnen neu- rowissenschaftlichen Fächer in eine dass ein Teil der vom Nervensystem portional ausbildende Neuhirn Disziplin zu überführen, die das geleisteten Arbeit dem Träger be- (Neencephalon), auf dem die höhe- Verhältnis von Gehirn und Be- wusst werden kann«.