Towards Generic Deobfuscation of Windows API Calls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAGIC Summoning: Towards Automatic Suggesting and Testing of Gestures with Low Probability of False Positives During Use

JournalofMachineLearningResearch14(2013)209-242 Submitted 10/11; Revised 6/12; Published 1/13 MAGIC Summoning: Towards Automatic Suggesting and Testing of Gestures With Low Probability of False Positives During Use Daniel Kyu Hwa Kohlsdorf [email protected] Thad E. Starner [email protected] GVU & School of Interactive Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332 Editors: Isabelle Guyon and Vassilis Athitsos Abstract Gestures for interfaces should be short, pleasing, intuitive, and easily recognized by a computer. However, it is a challenge for interface designers to create gestures easily distinguishable from users’ normal movements. Our tool MAGIC Summoning addresses this problem. Given a specific platform and task, we gather a large database of unlabeled sensor data captured in the environments in which the system will be used (an “Everyday Gesture Library” or EGL). The EGL is quantized and indexed via multi-dimensional Symbolic Aggregate approXimation (SAX) to enable quick searching. MAGIC exploits the SAX representation of the EGL to suggest gestures with a low likelihood of false triggering. Suggested gestures are ordered according to brevity and simplicity, freeing the interface designer to focus on the user experience. Once a gesture is selected, MAGIC can output synthetic examples of the gesture to train a chosen classifier (for example, with a hidden Markov model). If the interface designer suggests his own gesture and provides several examples, MAGIC estimates how accurately that gesture can be recognized and estimates its false positive rate by comparing it against the natural movements in the EGL. We demonstrate MAGIC’s effectiveness in gesture selection and helpfulness in creating accurate gesture recognizers. -

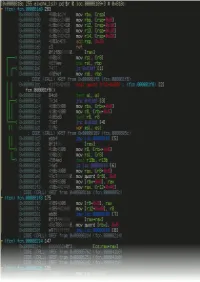

Radare2 Book

Table of Contents introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 History 1.2.1 Overview 1.2.2 Getting radare2 1.2.3 Compilation and Portability 1.2.4 Compilation on Windows 1.2.5 Command-line Flags 1.2.6 Basic Usage 1.2.7 Command Format 1.2.8 Expressions 1.2.9 Rax2 1.2.10 Basic Debugger Session 1.2.11 Contributing to radare2 1.2.12 Configuration 1.3 Colors 1.3.1 Common Configuration Variables 1.3.2 Basic Commands 1.4 Seeking 1.4.1 Block Size 1.4.2 Sections 1.4.3 Mapping Files 1.4.4 Print Modes 1.4.5 Flags 1.4.6 Write 1.4.7 Zoom 1.4.8 Yank/Paste 1.4.9 Comparing Bytes 1.4.10 Visual mode 1.5 Visual Disassembly 1.5.1 2 Searching bytes 1.6 Basic Searches 1.6.1 Configurating the Search 1.6.2 Pattern Search 1.6.3 Automation 1.6.4 Backward Search 1.6.5 Search in Assembly 1.6.6 Searching for AES Keys 1.6.7 Disassembling 1.7 Adding Metadata 1.7.1 ESIL 1.7.2 Scripting 1.8 Loops 1.8.1 Macros 1.8.2 R2pipe 1.8.3 Rabin2 1.9 File Identification 1.9.1 Entrypoint 1.9.2 Imports 1.9.3 Symbols (exports) 1.9.4 Libraries 1.9.5 Strings 1.9.6 Program Sections 1.9.7 Radiff2 1.10 Binary Diffing 1.10.1 Rasm2 1.11 Assemble 1.11.1 Disassemble 1.11.2 Ragg2 1.12 Analysis 1.13 Code Analysis 1.13.1 Rahash2 1.14 Rahash Tool 1.14.1 Debugger 1.15 3 Getting Started 1.15.1 Registers 1.15.2 Remote Access Capabilities 1.16 Remoting Capabilities 1.16.1 Plugins 1.17 Plugins 1.17.1 Crackmes 1.18 IOLI 1.18.1 IOLI 0x00 1.18.1.1 IOLI 0x01 1.18.1.2 Avatao 1.18.2 R3v3rs3 4 1.18.2.1 .intro 1.18.2.1.1 .radare2 1.18.2.1.2 .first_steps 1.18.2.1.3 .main 1.18.2.1.4 .vmloop 1.18.2.1.5 .instructionset 1.18.2.1.6 -

Android Malware and Analysis

ANDROID MALWARE AND ANALYSIS Ken Dunham • Shane Hartman Jose Andre Morales Manu Quintans • Tim Strazzere Click here to buy Android Malware and Analysis CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2015 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed on acid-free paper Version Date: 20140918 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4822-5219-4 (Hardback) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmit- ted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright. com (http://www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. -

Amigaos 3.2 FAQ 47.1 (09.04.2021) English

$VER: AmigaOS 3.2 FAQ 47.1 (09.04.2021) English Please note: This file contains a list of frequently asked questions along with answers, sorted by topics. Before trying to contact support, please read through this FAQ to determine whether or not it answers your question(s). Whilst this FAQ is focused on AmigaOS 3.2, it contains information regarding previous AmigaOS versions. Index of topics covered in this FAQ: 1. Installation 1.1 * What are the minimum hardware requirements for AmigaOS 3.2? 1.2 * Why won't AmigaOS 3.2 boot with 512 KB of RAM? 1.3 * Ok, I get it; 512 KB is not enough anymore, but can I get my way with less than 2 MB of RAM? 1.4 * How can I verify whether I correctly installed AmigaOS 3.2? 1.5 * Do you have any tips that can help me with 3.2 using my current hardware and software combination? 1.6 * The Help subsystem fails, it seems it is not available anymore. What happened? 1.7 * What are GlowIcons? Should I choose to install them? 1.8 * How can I verify the integrity of my AmigaOS 3.2 CD-ROM? 1.9 * My Greek/Russian/Polish/Turkish fonts are not being properly displayed. How can I fix this? 1.10 * When I boot from my AmigaOS 3.2 CD-ROM, I am being welcomed to the "AmigaOS Preinstallation Environment". What does this mean? 1.11 * What is the optimal ADF images/floppy disk ordering for a full AmigaOS 3.2 installation? 1.12 * LoadModule fails for some unknown reason when trying to update my ROM modules. -

Analyzing and Detecting Emerging Internet of Things Malware: a Graph-Based Approach

This is the author's version of an article that has been published in this journal. Changes were made to this version by the publisher prior to publication. The final version of record is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2019.2925929 1 Analyzing and Detecting Emerging Internet of Things Malware: A Graph-based Approach Hisham Alasmaryzy, Aminollah Khormaliy, Afsah Anwary, Jeman Parky, Jinchun Choi{y, Ahmed Abusnainay, Amro Awady, DaeHun Nyang{, and Aziz Mohaiseny yUniversity of Central Florida zKing Khalid University {Inha University Abstract—The steady growth in the number of deployed Linux-like capabilities. In particular, Busybox is widely used Internet of Things (IoT) devices has been paralleled with an equal to achieve the desired functionality; based on a light-weighted growth in the number of malicious software (malware) targeting structure, it supports utilities needed for IoT devices. those devices. In this work, we build a detection mechanism of IoT malware utilizing Control Flow Graphs (CFGs). To motivate On the other hand, and due to common structures, the for our detection mechanism, we contrast the underlying char- Linux capabilities of the IoT systems inherit and extend the acteristics of IoT malware to other types of malware—Android potential threats to the Linux system. Executable and Linkable malware, which are also Linux-based—across multiple features. Format (ELF), a standard format for executable and object The preliminary analyses reveal that the Android malware have code, is sometimes exploited as an object of malware. The high density, strong closeness and betweenness, and a larger number of nodes. -

Understanding and Mitigating the Security Risks of Apple Zeroconf

2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy Staying Secure and Unprepared: Understanding and Mitigating the Security Risks of Apple ZeroConf Xiaolong Bai*,1, Luyi Xing*,2, Nan Zhang2, XiaoFeng Wang2, Xiaojing Liao3, Tongxin Li4, Shi-Min Hu1 1TNList, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 2Indiana University Bloomington, 3Georgia Institute of Technology, 4Peking University [email protected], {luyixing, nz3, xw7}@indiana.edu, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—With the popularity of today’s usability-oriented tend to build their systems in a “plug-and-play” fashion, designs, dubbed Zero Configuration or ZeroConf, unclear are using techniques dubbed zero-configuration (ZeroConf ). For the security implications of these automatic service discovery, example, the AirDrop service on iPhone, once activated, “plug-and-play” techniques. In this paper, we report the first systematic study on this issue, focusing on the security features automatically detects another Apple device nearby running of the systems related to Apple, the major proponent of the service to transfer documents. Such ZeroConf services ZeroConf techniques. Our research brings to light a disturb- are characterized by automatic IP selection, host name ing lack of security consideration in these systems’ designs: resolving and target service discovery. Prominent examples major ZeroConf frameworks on the Apple platforms, includ- include Apple’s Bonjour [3], and the Link-Local Multicast ing the Core Bluetooth Framework, Multipeer Connectivity and -

Cooper ( Interaction Design

Cooper ( Interaction Design Inspiration The Myth of Metaphor Cooper books by Alan Cooper, Chairman & Founder Articles June 1995 Newsletter Originally Published in Visual Basic Programmer's Journal Concept projects Book reviews Software designers often speak of "finding the right metaphor" upon which to base their interface design. They imagine that rendering their user interface in images of familiar objects from the real world will provide a pipeline to automatic learning by their users. So they render their user interface as an office filled with desks, file cabinets, telephones and address books, or as a pad of paper or a street of buildings in the hope of creating a program with breakthrough ease-of- learning. And if you search for that magic metaphor, you will be in august company. Some of the best and brightest designers in the interface world put metaphor selection as one of their first and most important tasks. But by searching for that magic metaphor you will be making one of the biggest mistakes in user interface design. Searching for that guiding metaphor is like searching for the correct steam engine to power your airplane, or searching for a good dinosaur on which to ride to work. I think basing a user interface design on a metaphor is not only unhelpful but can often be quite harmful. The idea that good user interface design is based on metaphors is one of the most insidious of the many myths that permeate the software community. Metaphors offer a tiny boost in learnability to first time users at http://www.cooper.com/articles/art_myth_of_metaphor.htm (1 of 8) [1/16/2002 2:21:34 PM] Cooper ( Interaction Design tremendous cost. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Efficient Bug Prediction and Fix Suggestions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/47x1t79s Author Shivaji, Shivkumar Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EFFICIENT BUG PREDICTION AND FIX SUGGESTIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Shivkumar Shivaji March 2013 The Dissertation of Shivkumar Shivaji is approved: Professor Jim Whitehead, Chair Professor Jose Renau Professor Cormac Flanagan Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Shivkumar Shivaji 2013 Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgments x Dedication xi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivation . .1 1.2 Bug Prediction Workflow . .9 1.3 Bug Prognosticator . 10 1.4 Fix Suggester . 11 1.5 Human Feedback . 11 1.6 Contributions and Research Questions . 12 2 Related Work 15 2.1 Defect Prediction . 15 2.1.1 Totally Ordered Program Units . 16 2.1.2 Partially Ordered Program Units . 18 2.1.3 Prediction on a Given Software Unit . 19 2.2 Predictions of Bug Introducing Activities . 20 2.3 Predictions of Bug Characteristics . 21 2.4 Feature Selection . 24 2.5 Fix Suggestion . 25 2.5.1 Static Analysis Techniques . 25 2.5.2 Fix Content Prediction without Static Analysis . 26 2.6 Human Feedback . 28 iii 3 Change Classification 30 3.1 Workflow . 30 3.2 Finding Buggy and Clean Changes . -

Android Reverse Engineering: Understanding Third-Party Applications

Android reverse engineering: understanding third-party applications Vicente Aguilera Díaz OWASP Spain Chapter Leader Co-founder of Internet Security Auditors [email protected] Twitter: @vaguileradiaz www.vicenteaguileradiaz.com OWASP EU Tour 2013 Copyright © The OWASP Foundation June 5, 2013. Bucharest (Romania) Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the OWASP License. The OWASP Foundation http://www.owasp.org Who I am? VICENTE AGUILERA DÍAZ Co-founder of Internet Security Auditors OWASP Spain Chapter Leader More info: www.vicenteaguileradiaz.com OWASP 2 Agenda Reverse engineering: definition and objectives Application analysis workflow Malware identification in Android apps OWASP 3 Reverse engineering: definition and objectives Definition Refers to the process of analyzing a system to identify its components and their interrelationships, and create representations of the system in another form or a higher level of abstraction. [1] Objetives The purpose of reverse engineering is not to make changes or to replicate the system under analysis, but to understand how it was built. OWASP 4 Application analysis workflow Original APK Analyze Decompress and Rebuild Dissassemble APK Modify Scope of this presentation Modified APK OWASP 5 Application analysis workflow App Name SaveAPK Astro File Manager Real APK Leecher APK apktool radare2 unzip AndroidManifest.xml /lib apktool.yml /META-INF /assets /res /res resources.arsc AXMLPrinter2.jar Disasm /smali AndroidManifest.xml Human-readable -

![Arxiv:1611.10231V1 [Cs.CR] 30 Nov 2016 a INTRODUCTION 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4076/arxiv-1611-10231v1-cs-cr-30-nov-2016-a-introduction-1-1544076.webp)

Arxiv:1611.10231V1 [Cs.CR] 30 Nov 2016 a INTRODUCTION 1

00 Android Code Protection via Obfuscation Techniques: Past, Present and Future Directions Parvez Faruki, Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur, India Hossein Fereidooni, University of Padua, Italy Vijay Laxmi, Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur, India Mauro Conti, University of Padua, Italy Manoj Gaur, Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur, India Mobile devices have become ubiquitous due to centralization of private user information, contacts, messages and multiple sensors. Google Android, an open-source mobile Operating System (OS), is currently the mar- ket leader. Android popularity has motivated the malware authors to employ set of cyber attacks leveraging code obfuscation techniques. Obfuscation is an action that modifies an application (app) code, preserving the original semantics and functionality to evade anti-malware. Code obfuscation is a contentious issue. Theoretical code analysis techniques indicate that, attaining a verifiable and secure obfuscation is impos- sible. However, obfuscation tools and techniques are popular both among malware developers (to evade anti-malware) and commercial software developers (protect intellectual rights). We conducted a survey to uncover answers to concrete and relevant questions concerning Android code obfuscation and protection techniques. The purpose of this paper is to review code obfuscation and code protection practices, and evalu- ate efficacy of existing code de-obfuscation tools. In particular, we discuss Android code obfuscation methods, custom app protection techniques, and various de-obfuscation methods. Furthermore, we review and ana- lyze the obfuscation techniques used by malware authors to evade analysis efforts. We believe that, there is a need to investigate efficiency of the defense techniques used for code protection. This survey would be beneficial to the researchers and practitioners, to understand obfuscation and de-obfuscation techniques to propose novel solutions on Android. -

Automatic Program Repair Using Genetic Programming

Automatic Program Repair Using Genetic Programming A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) by Claire Le Goues May 2013 c 2013 Claire Le Goues Abstract Software quality is an urgent problem. There are so many bugs in industrial program source code that mature software projects are known to ship with both known and unknown bugs [1], and the number of outstanding defects typically exceeds the resources available to address them [2]. This has become a pressing economic problem whose costs in the United States can be measured in the billions of dollars annually [3]. A dominant reason that software defects are so expensive is that fixing them remains a manual process. The process of identifying, triaging, reproducing, and localizing a particular bug, coupled with the task of understanding the underlying error, identifying a set of code changes that address it correctly, and then verifying those changes, costs both time [4] and money. Moreover, the cost of repairing a defect can increase by orders of magnitude as development progresses [5]. As a result, many defects, including critical security defects [6], remain unaddressed for long periods of time [7]. Moreover, humans are error-prone, and many human fixes are imperfect, in that they are either incorrect or lead to crashes, hangs, corruption, or security problems [8]. As a result, defect repair has become a major component of software maintenance, which in turn consumes up to 90% of the total lifecycle cost of a given piece of software [9]. -

Intuition As Evidence in Philosophical Analysis: Taking Connectionism Seriously

Intuition as Evidence in Philosophical Analysis: Taking Connectionism Seriously by Tom Rand A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Philosophy University of Toronto (c) Copyright by Tom Rand 2008 Intuition as Evidence in Philosophical Analysis: Taking Connectionism Seriously Ph.D. Degree, 2008, by Tom Rand, Graduate Department of Philosophy, University of Toronto ABSTRACT 1. Intuitions are often treated in philosophy as a basic evidential source to confirm/discredit a proposed definition or theory; e.g. intuitions about Gettier cases are taken to deny a justified-true-belief analysis of ‘knowledge’. Recently, Weinberg, Nichols & Stitch (WN&S) provided evidence that epistemic intuitions vary across persons and cultures. In- so-far as philosophy of this type (Standard Philosophical Methodology – SPM) is committed to provide conceptual analyses, the use of intuition is suspect – it does not exhibit the requisite normativity. I provide an analysis of intuition, with an emphasis on its neural – or connectionist – cognitive backbone; the analysis provides insight into its epistemic status and proper role within SPM. Intuition is initially characterized as the recognition of a pattern. 2. The metaphysics of ‘pattern’ is analyzed for the purpose of denying that traditional symbolic computation is capable of differentiating the patterns of interest. 3. The epistemology of ‘recognition’ is analyzed, again, to deny that traditional computation is capable of capturing human acts of recognition. 4. Fodor’s informational semantics, his Language of Thought and his Representational Theory of Mind are analyzed and his arguments denied. Again, the purpose is to deny traditional computational theories of mind.