Ground-Living Spider Assemblages from Mediterranean Habitats Under Different Management Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphological Evolution of Spiders Predicted by Pendulum Mechanics

Morphological Evolution of Spiders Predicted by Pendulum Mechanics Jordi Moya-Laran˜ o1*, Dejan Vinkovic´2, Eva De Mas1, Guadalupe Corcobado1, Eulalia Moreno1 1 Departamento de Ecologı´a Funcional y Evolutiva, Estacio´n Experimental de Zonas A´ ridas, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientı´ficas (CSIC), Almerı´a, Spain, 2 Physics Department, University of Split, Split, Croatia Abstract Background: Animals have been hypothesized to benefit from pendulum mechanics during suspensory locomotion, in which the potential energy of gravity is converted into kinetic energy according to the energy-conservation principle. However, no convincing evidence has been found so far. Demonstrating that morphological evolution follows pendulum mechanics is important from a biomechanical point of view because during suspensory locomotion some morphological traits could be decoupled from gravity, thus allowing independent adaptive morphological evolution of these two traits when compared to animals that move standing on their legs; i.e., as inverted pendulums. If the evolution of body shape matches simple pendulum mechanics, animals that move suspending their bodies should evolve relatively longer legs which must confer high moving capabilities. Methodology/Principal Findings: We tested this hypothesis in spiders, a group of diverse terrestrial generalist predators in which suspensory locomotion has been lost and gained a few times independently during their evolutionary history. In spiders that hang upside-down from their webs, their legs have evolved disproportionately longer relative to their body sizes when compared to spiders that move standing on their legs. In addition, we show how disproportionately longer legs allow spiders to run faster during suspensory locomotion and how these same spiders run at a slower speed on the ground (i.e., as inverted pendulums). -

Distribution of Spiders in Coastal Grey Dunes

kaft_def 7/8/04 11:22 AM Pagina 1 SPATIAL PATTERNS AND EVOLUTIONARY D ISTRIBUTION OF SPIDERS IN COASTAL GREY DUNES Distribution of spiders in coastal grey dunes SPATIAL PATTERNS AND EVOLUTIONARY- ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF DISPERSAL - ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF DISPERSAL Dries Bonte Dispersal is crucial in structuring species distribution, population structure and species ranges at large geographical scales or within local patchily distributed populations. The knowledge of dispersal evolution, motivation, its effect on metapopulation dynamics and species distribution at multiple scales is poorly understood and many questions remain unsolved or require empirical verification. In this thesis we contribute to the knowledge of dispersal, by studying both ecological and evolutionary aspects of spider dispersal in fragmented grey dunes. Studies were performed at the individual, population and assemblage level and indicate that behavioural traits narrowly linked to dispersal, con- siderably show [adaptive] variation in function of habitat quality and geometry. Dispersal also determines spider distribution patterns and metapopulation dynamics. Consequently, our results stress the need to integrate knowledge on behavioural ecology within the study of ecological landscapes. / Promotor: Prof. Dr. Eckhart Kuijken [Ghent University & Institute of Nature Dries Bonte Conservation] Co-promotor: Prf. Dr. Jean-Pierre Maelfait [Ghent University & Institute of Nature Conservation] and Prof. Dr. Luc lens [Ghent University] Date of public defence: 6 February 2004 [Ghent University] Universiteit Gent Faculteit Wetenschappen Academiejaar 2003-2004 Distribution of spiders in coastal grey dunes: spatial patterns and evolutionary-ecological importance of dispersal Verspreiding van spinnen in grijze kustduinen: ruimtelijke patronen en evolutionair-ecologisch belang van dispersie door Dries Bonte Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor [Ph.D.] in Sciences Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Doctor in de Wetenschappen Promotor: Prof. -

A Summary List of Fossil Spiders

A summary list of fossil spiders compiled by Jason A. Dunlop (Berlin), David Penney (Manchester) & Denise Jekel (Berlin) Suggested citation: Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders. In Platnick, N. I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 10.5. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html Last udated: 10.12.2009 INTRODUCTION Fossil spiders have not been fully cataloged since Bonnet’s Bibliographia Araneorum and are not included in the current Catalog. Since Bonnet’s time there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the spider fossil record and numerous new taxa have been described. As part of a larger project to catalog the diversity of fossil arachnids and their relatives, our aim here is to offer a summary list of the known fossil spiders in their current systematic position; as a first step towards the eventual goal of combining fossil and Recent data within a single arachnological resource. To integrate our data as smoothly as possible with standards used for living spiders, our list follows the names and sequence of families adopted in the Catalog. For this reason some of the family groupings proposed in Wunderlich’s (2004, 2008) monographs of amber and copal spiders are not reflected here, and we encourage the reader to consult these studies for details and alternative opinions. Extinct families have been inserted in the position which we hope best reflects their probable affinities. Genus and species names were compiled from established lists and cross-referenced against the primary literature. -

First Record of the Jumping Spider Icius Subinermis (Araneae, Salticidae) in Hungary 38-40 © Arachnologische Gesellschaft E.V

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arachnologische Mitteilungen Jahr/Year: 2017 Band/Volume: 54 Autor(en)/Author(s): Koranyi David, Mezöfi Laszlo, Marko Laszlo Artikel/Article: First record of the jumping spider Icius subinermis (Araneae, Salticidae) in Hungary 38-40 © Arachnologische Gesellschaft e.V. Frankfurt/Main; http://arages.de/ Arachnologische Mitteilungen / Arachnology Letters 54: 38-40 Karlsruhe, September 2017 First record of the jumping spider Icius subinermis (Araneae, Salticidae) in Hungary Dávid Korányi, László Mezőfi & Viktor Markó doi: 10.5431/aramit5408 Abstract. We report the first record of Icius subinermis Simon, 1937, one female, from Budapest, Hungary. We provide photographs of the habitus and of the copulatory organ. The possible reasons for the new record and the current jumping spider fauna (Salticidae) of Hungary are discussed. So far 77 salticid species (including I. subinermis) are known from Hungary. Keywords: distribution, faunistics, introduced species, urban environment Zusammenfassung. Erstnachweis der Springspinne Icius subinermis (Araneae, Salticidae) aus Ungarn. Wir berichten über den ersten Nachweis von Icius subinermis Simon, 1937, eines Weibchens, aus Budapest, Ungarn. Fotos des weiblichen Habitus und des Ko- pulationsorgans werden präsentiert. Mögliche Ursachen für diesen Neunachweis und die Zusammensetzung der Springspinnenfauna Ungarns werden diskutiert. Bisher sind 77 Springspinnenarten (einschließlich I. subinermis) aus Ungarn bekannt. The spider fauna of Hungary is well studied (Samu & Szi- The specimen was collected on June 22nd 2016 using the bea- netár 1999). Due to intensive research and more specialized ting method. The study was carried out at the Department collecting methods, new records frequently emerge. -

Programa De Doutoramento Em Biologia ”Dinâmica Das

Universidade de Evora´ - Instituto de Investiga¸c~aoe Forma¸c~aoAvan¸cada Programa de Doutoramento em Biologia Tese de Doutoramento "Din^amicadas comunidades de grupos selecionados de artr´opodes terrestres nas ´areasemergentes da Barragem de Alqueva (Alentejo: Portugal) Rui Jorge Cegonho Raimundo Orientador(es) j Diogo Francisco Caeiro Figueiredo Paulo Alexandre Vieira Borges Evora´ 2020 Universidade de Evora´ - Instituto de Investiga¸c~aoe Forma¸c~aoAvan¸cada Programa de Doutoramento em Biologia Tese de Doutoramento "Din^amicadas comunidades de grupos selecionados de artr´opodes terrestres nas ´areasemergentes da Barragem de Alqueva (Alentejo: Portugal) Rui Jorge Cegonho Raimundo Orientador(es) j Diogo Francisco Caeiro Figueiredo Paulo Alexandre Vieira Borges Evora´ 2020 A tese de doutoramento foi objeto de aprecia¸c~aoe discuss~aop´ublicapelo seguinte j´urinomeado pelo Diretor do Instituto de Investiga¸c~aoe Forma¸c~ao Avan¸cada: Presidente j Luiz Carlos Gazarini (Universidade de Evora)´ Vogais j Am´aliaMaria Marques Espirid~aode Oliveira (Universidade de Evora)´ Artur Raposo Moniz Serrano (Universidade de Lisboa - Faculdade de Ci^encias) Fernando Manuel de Campos Trindade Rei (Universidade de Evora)´ M´arioRui Canelas Boieiro (Universidade dos A¸cores) Paulo Alexandre Vieira Borges (Universidade dos A¸cores) (Orientador) Pedro Segurado (Universidade T´ecnicade Lisboa - Instituto Superior de Agronomia) Evora´ 2020 IV Ilhas. Trago uma comigo in visível, um pedaço de matéria isolado e denso, que se deslocou numa catástrofe da idade média. Enquanto ilha, não carece de mar. Nem de nuvens passageiras. Enquanto fragmento, só outra catástrofe a devolveria ao corpo primitivo. Dora Neto V VI AGRADECIMENTOS Os momentos e decisões ao longo da vida tornaram-se pontos de inflexão que surgiram de um simples fascínio pelos invertebrados, reminiscência de infância passada na quinta dos avós maternos, para se tornar numa opção científica consubstanciada neste documento. -

Assessing Spider Species Richness and Composition in Mediterranean Cork Oak Forests

acta oecologica 33 (2008) 114–127 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actoec Original article Assessing spider species richness and composition in Mediterranean cork oak forests Pedro Cardosoa,b,c,*, Clara Gasparc,d, Luis C. Pereirae, Israel Silvab, Se´rgio S. Henriquese, Ricardo R. da Silvae, Pedro Sousaf aNatural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum and Centre for Macroecology, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark bCentre of Environmental Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Rua Ernesto de Vasconcelos Ed. C2, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal cAgricultural Sciences Department – CITA-A, University of Azores, Terra-Cha˜, 9701-851 Angra do Heroı´smo, Portugal dBiodiversity and Macroecology Group, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK eDepartment of Biology, University of E´vora, Nu´cleo da Mitra, 7002-554 E´vora, Portugal fCIBIO, Research Centre on Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, University of Oporto, Campus Agra´rio de Vaira˜o, 4485-661 Vaira˜o, Portugal article info abstract Article history: Semi-quantitative sampling protocols have been proposed as the most cost-effective and Received 8 January 2007 comprehensive way of sampling spiders in many regions of the world. In the present study, Accepted 3 October 2007 a balanced sampling design with the same number of samples per day, time of day, collec- Published online 19 November 2007 tor and method, was used to assess the species richness and composition of a Quercus suber woodland in Central Portugal. A total of 475 samples, each corresponding to one hour of Keywords: effective fieldwork, were taken. -

Anticancer Compounds from Medicinal Plants

BIOLOGICA NYSSANA 2 (2) December 2011: 00-00 Ljupković R.B. et al.. Removal Cu(II) ions from water... 3 (1) • September 2012: 37-42 Original Article Contribution to the knowledge of jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) from vicinity of Jagodina, Central Serbia Boban Stanković1* 1 City Goverment of Jagodina, Department of Environmental Protection, Kralja Petra I, No 6, 35000 Jagodina, Serbia * E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Stanković, B.: Contribution to the knowledge of jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) from vicinity of Jagodina, Central Serbia, Biologica Nyssana, 3 (1), September 2012: 37-42. During last 10 years, based on personal collectings, 21 species from 14 genera of Salticidae (Araneae) are recorded from vicinity of Jagodina: Ballus chalybeius, Carrhotus xanthogramma, Evarcha arcuata, Evarcha falcata, Heliophanus auratus, Heliophanus cupreus, Heliophanus flavipes, Heliophanus kochii, Icius hamatus, Icius subinermis, Leptorchestes berolinensis, Macaroeris nidicolens, Marpissa muscosa, Marpissa nivoyi, Mendoza canestrinii, Pellenes tripunctatus, Phintella castriesiana, Phlegra fasciata, Pseudeuophrys erratica, Pseudeuophrys lanigera, Salticus scenicus. All those species are provided with habitat notes and global distribution. New records for the spider fauna of Serbia are Heliophanus kochii (Simon 1868), Icius subinermis (Simon, 1937), Marpissa nivoyi (Lucas, 1846) and Mendoza canestrinii (Ninni, 1868). Key words: Salticidae, Jumping spiders, Jagodina, Serbia. Introduction zoogeographic analysis are presented. New species records for the spider fauna of Serbia are: The Salticidae Blackwall, 1841 or jumping Heliophanus kochii (Simon, 1868), Icius subinermis spiders, are the most diverse globally distributed (Simon, 1937), Marpissa nivoyi (Lucas, 1846) and spider family mostly tropical, with 5337 species Mendoza canestrinii (Ninni, 1868). placed in 573 genera (P l a t n i c k , 2011). -

(ARANEA) for the FAUNA of SERBIA the Salticidae, Or Jumping

Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, 2010, 3: 133-136. Received 1 Jun 2010; Accepted 9 Nov 2010. UDC: 595.44(497.11) Short communication TWO NEW SPECIES OF SALTICIDAE (ARANEA) FOR THE FAUNA OF SERBIA BOBAN STANKOVIĆ City Administration of Jagodina, Department of Environmental Protection, Kralja Petra I, 35000 Jagodina, Serbia, e-mail: [email protected] The Salticidae, or jumping spiders, are the most diverse spider family, with over 5000 species (Platnick 2008), most of which are tropical. This spider’s fauna are insufficiently studied in Serbia. According to Deltshev et al. (2003), only 49 species of jumping spiders have been recorded in Serbia. This is a small number compared to surrounding countries: 91 species are recorded in Bulgaria (Deltshev 2005), 84 in Croatia (Nikolić & Polenec 1981, Katušić 2008), 84 in Romania, 70 in Hungary (Szuts et al. 2003) and 58 in Macedonia (van Helsdingen 2007). In the present paper, two jumping spider species of the family Salticidae are reported as new for the fauna of Serbia. All specimens of the jumping spiders species were collected in the Jagodina region (the central part of Serbia) (UTM EP26; 21°14‘-21°16‘ 43°57‘-44°01; altitude range 118-229m). The climate is moderately conti- nental. According to the relevant meteorological station in Ćuprija, the average annual air temperatures are between 11.2 and 11.7°C approxi- 134 STANKOVIĆ, B.: TWO NEW SPECIES OF SALTICIDAE IN SERBIA mately, and the average annual rainfall is 619 mm. During the eight month period of March-November, the average monthly air temperatures were higher to 10°C. -

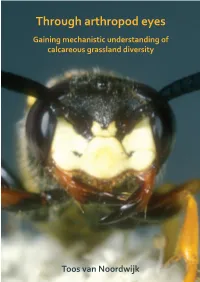

Through Arthropod Eyes Gaining Mechanistic Understanding of Calcareous Grassland Diversity

Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Toos van Noordwijk Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Van Noordwijk, C.G.E. 2014. Through arthropod eyes. Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity. Ph.D. thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Keywords: Biodiversity, chalk grassland, dispersal tactics, conservation management, ecosystem restoration, fragmentation, grazing, insect conservation, life‑history strategies, traits. ©2014, C.G.E. van Noordwijk ISBN: 978‑90‑77522‑06‑6 Printed by: Gildeprint ‑ Enschede Lay‑out: A.M. Antheunisse Cover photos: Aart Noordam (Bijenwolf, Philanthus triangulum) Toos van Noordwijk (Laamhei) The research presented in this thesis was financially spupported by and carried out at: 1) Bargerveen Foundation, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 2) Department of Animal Ecology and Ecophysiology, Institute for Water and Wetland Research, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 3) Terrestrial Ecology Unit, Ghent University, Belgium. The research was in part commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation as part of the O+BN program (Development and Management of Nature Quality). Financial support from Radboud University for printing this thesis is gratefully acknowledged. Through arthropod eyes Gaining mechanistic understanding of calcareous grassland diversity Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann volgens besluit van het college van decanen en ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de biologie aan de Universiteit Gent op gezag van de rector prof. dr. Anne De Paepe, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 26 augustus 2014 om 10.30 uur precies door Catharina Gesina Elisabeth van Noordwijk geboren op 9 februari 1981 te Smithtown, USA Promotoren: Prof. -

The Role of Mating Systems in Sexual Selection in Parasitoid Wasps

Biol. Rev. (2014), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12126 Beyond sex allocation: the role of mating systems in sexual selection in parasitoid wasps Rebecca A. Boulton∗, Laura A. Collins and David M. Shuker Centre for Biological Diversity, School of Biology, University of St Andrews, Dyers Brae, Greenside place, Fife KY16 9TH, U.K. ABSTRACT Despite the diverse array of mating systems and life histories which characterise the parasitic Hymenoptera, sexual selection and sexual conflict in this taxon have been somewhat overlooked. For instance, parasitoid mating systems have typically been studied in terms of how mating structure affects sex allocation. In the past decade, however, some studies have sought to address sexual selection in the parasitoid wasps more explicitly and found that, despite the lack of obvious secondary sexual traits, sexual selection has the potential to shape a range of aspects of parasitoid reproductive behaviour and ecology. Moreover, various characteristics fundamental to the parasitoid way of life may provide innovative new ways to investigate different processes of sexual selection. The overall aim of this review therefore is to re-examine parasitoid biology with sexual selection in mind, for both parasitoid biologists and also researchers interested in sexual selection and the evolution of mating systems more generally. We will consider aspects of particular relevance that have already been well studied including local mating structure, sex allocation and sperm depletion. We go on to review what we already know about sexual selection in the parasitoid wasps and highlight areas which may prove fruitful for further investigation. In particular, sperm depletion and the costs of inbreeding under chromosomal sex determination provide novel opportunities for testing the role of direct and indirect benefits for the evolution of mate choice. -

Facultad De Ciencias Experimentales

UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales Trabajo Fin de Grado Determinación de la aracnofauna de la comarca de La Campiña de Córdoba. Alumna: Isabel María Sánchez León Facultad de Ciencias Experimentales Julio, 2019 1 ÍNDICE 1. Resumen 4 2. Introducción 5 2.1. Aspectos morfológicos 5 2.2. Ciclo biológico y reproducción 9 2.3. Diversidad del orden Araneae 11 2.4. Ecología 12 3. Objetivos 14 4. Material y métodos 14 4.1. Área de estudio 14 4.1.1. Puntos de muestreo 16 4.1.1.1. Parcela 1 16 4.1.1.2. Parcela 2 16 4.1.1.3. Parcela 3 17 4.1.1.4. Parcela 4 17 4.1.2. Geología y suelo 18 4.1.3. Vegetación 18 4.1.4. Climatología 18 4.2. Método de captura 23 4.3. Conservación y determinación de las arañas 24 5. Resultados 25 5.1. Determinación de las arañas de la campiña cordobesa 25 5.2. Arañas más representativas de la Campiña de Córdoba 29 5.2.1. Familia Gnaphosidae 29 5.2.2. Familia Lycosidae 30 5.2.3. Familia Oecobiidae 31 5.2.4. Familia Salticidae 32 5.2.5. Familia Sicariidae 32 5.2.6. Familia Theridiidae 33 5.2.7. Familia Thomisidae 34 5.2.8. Familia Zodariidae 34 5.2.9. Otras familias capturadas 35 6. Discusión 35 7. Conclusiones 38 8. Referencias bibliográficas 39 9. Anexos 42 3 1. RESUMEN En este trabajo se ha llevado a cabo un estudio sobre la biodiversidad a nivel de familias del Orden Araneae en cuatro zonas diferentes, dos de ellas han sido zona de olivar y otras dos zona de viñas. -

Stones on the Ground in Olive Groves Promote the Presence of Spiders (Araneae)

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 372–379, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.037 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Stones on the ground in olive groves promote the presence of spiders (Araneae) JACINTO BENHADI-MARÍN 1, 2, JOSÉ A. PEREIRA1, JOSÉ A. BARRIENTOS 3, JOSÉ P. SOUSA2 and SÓNIA A.P. SANTOS 4, 5 1 Centro de Investigação de Montanha (CIMO), ESA, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Campus de Santa Apolónia, 5300-253 Bragança, Portugal; e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Centre for Functional Ecology, Department of Life Sciences, University of Coimbra, Calçada Martim de Freitas, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal; e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Animal Biology, Plant Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Biosciences, Autonomous University of Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; e-mail: [email protected] 4 CIQuiBio, Barreiro School of Technology, Polytechnic Institute of Setúbal, Rua Américo da Silva Marinho, 2839-001 Lavradio, Portugal; e-mail: [email protected] 5 LEAF, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal Key words. Araneae, biological control, ground hunter, predator, abundance, diversity, shelter Abstract. Spiders are generalist predators that contribute to the control of pests in agroecosystems. Land use management determines habitats including refuges for hibernation and aestivation. The availability of shelters on the ground can be crucial for maintaining populations of spider within crops. We studied the effect of the number of stones on the surface of the soil on the spi- der community in selected olive groves in Trás-os-Montes (northeastern Portugal).