Lo Bashamayim Hi (It [The Torah] Is Not in Heaven)!’1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing the Talmud: the Origins of the Printed Talmudic Page

Marvin J. Heller The author has published Printing the Talmud: A History of the Earliest Printed Editions of the Talmud. DESIGNING THE TALMUD: THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINTED TALMUDIC PAGE non-biblical Jewish work,i Its redaction was completed at the The Talmudbeginning is indisputablyof the fifth century the most and the important most important and influential commen- taries were written in the middle ages. Studied without interruption for a milennium and a half, it is surprising just how significant an eftèct the invention of printing, a relatively late occurrence, had upon the Talmud. The ramifications of Gutenberg's invention are well known. One of the consequences not foreseen by the early practitioners of the "Holy Work" and commonly associated with the Industrial Revolution, was the introduction of standardization. The spread of printing meant that distinct scribal styles became generic fonts, erratic spellngs became uni- form and sequential numbering of pages became standard. The first printed books (incunabula) were typeset copies of manu- scripts, lacking pagination and often not uniform. As a result, incunabu- la share many characteristics with manuscripts, such as leaving a blank space for the first letter or word to be embellshed with an ornamental woodcut, a colophon at the end of the work rather than a title page, and the use of signatures but no pagination.2 The Gutenberg Bibles, for example, were printed with blank spaces to be completed by calligra- phers, accounting for the varying appearance of the surviving Bibles. Hebrew books, too, shared many features with manuscripts; A. M. Habermann writes that "Conats type-faces were cast after his own handwriting, . -

Gemara Succah Elementary I and II

PREMIUMPREMIUM TORAHTORAH COLLEGECOLLEGE PROGRAMSPROGRAMSTaTa l l Gemara Succah Elementary I and II February 2019 Elementary Gemara I and II: Succah —Study Guide— In this Study Guide you will find: • Elementary Succah I: syllabus (page 4), and sample examination (page 11). • Elementary Succah II: syllabus (page 18), and sample examination (page 25). NOTE: a. Since you are required to answer in black ink, be sure to bring a black pen to your exam. b. Accustom yourself to outlining your answers on scrap paper and writing essays clearly. Illegible exams will not be graded. c. The lowest passing score on this exam is 70. You will not get credit for a score below 70, though in the case of a failed or illegible paper, you may be able to retake the exam after waiting six months. Grades for transcripts are calculated as follows: A = 90–100% B = 80–89% C = 70–79% This Study Guide is the property of TAL and MUST be returned after you take the exam. Failure to do so is an aveirah of gezel. GemaraSuccahElemIandIISPCombined-1 v02.indd © 2019 by Torah Accreditation Liaison. All Rights Reserved. Succah Elementary I and II Elementary Gemara I: Succah — Study Guide — This elementary Gemara I examination is based on the beginning of Maseches Succah, from: דף ד עמוד ב on (ושאינה גבוהה עשרה טפחים) 2a) until the two dots) דף ב עמוד א • (4b), and דף ז עמוד א 6b) through) דף ו עמוד ב on (ושאין לה שלש דפנות) from the two dots • .(on the last line גופא 7a) (until the word) In this Study Guide you will find: • The syllabus outline for the elementary Succah I examination (page 4). -

Humor in Torah and Talmud

Sat 3 July 2010 Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Lunch and Learn Humor in Torah and Talmud -Not general presentation on Jewish humor, just humor in Tanach and Talmud, and list below is far from exhaustive -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Some commentators say humor is not intentional. -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th cent. Talmudist) always began his lectures with a joke: Before starting to teach, Rabbah joked and pupils laughed. Afterwards he started seriously teaching halachah. (Talmud, Shabbat 30b) Humor in Tanach -Sarai can’t conceive, so she tells her husband Abram: I beg you, go in to my maid [Hagar]; perhaps I can obtain children through her. And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai. [Genesis 16:2] Hagar gets pregnant and becomes very impertinent towards her mistress Sarai. So a very angry Sarai goes to her husband Abram and tells him: This is all your fault! [Genesis 16:5 ] -God tells Sarah she will have a child: And Sarah laughed, saying: Shall I have pleasure when I am old? My husband is also old. And the Lord said to Abraham [who did not hear Sarah]: “Why did Sarah laugh, saying: Shall I bear a child, when I am old?” [Genesis 18:12-13] God does not report all that Sarah said for shalom bayit -- to keep peace in the family. Based on this, Talmud concludes it’s OK to tell white lies [Bava Metzia 87a]. Note: After Sarah dies Abraham marries Keturah and has six more sons. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Humor in Talmud and Midrash

Tue 14, 21, 28 Apr 2015 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Jewish Community Center of Northern Virginia Adult Learning Institute Jewish Humor Through the Sages Contents Introduction Warning Humor in Tanach Humor in Talmud and Midrash Desire for accuracy Humor in the phrasing The A-Fortiori argument Stories of the rabbis Not for ladies The Jewish Sherlock Holmes Checks and balances Trying to fault the Torah Fervor Dreams Lying How many infractions? Conclusion Introduction -Not general presentation on Jewish humor: Just humor in Tanach, Talmud, Midrash, and other ancient Jewish sources. -Far from exhaustive. -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Talmud: Records teachings of more than 1,000 rabbis spanning 7 centuries (2nd BCE to 5th CE). Basis of all Jewish law. -Savoraim improved style in 6th-7th centuries CE. -Rabbis dream up hypothetical situations that are strange, farfetched, improbable, or even impossible. -To illustrate legal issues, entertain to make study less boring, and sharpen the mind with brainteasers. 1 -Going to extremes helps to understand difficult concepts. (E.g., Einstein's “thought experiments”.) -Some commentators say humor is not intentional: -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th century CE) always began his lectures with a joke: Before he began his lecture to the scholars, [Rabbah] used to say something funny, and the scholars were cheered. After that, he sat in awe and began the lecture. [Shabbat 30b] -Laughing and entertaining are important. Talmud: -Rabbi Beroka Hoza'ah often went to the marketplace at Be Lapat, where [the prophet] Elijah often appeared to him. -

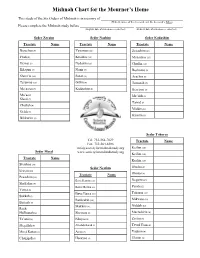

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Rabbinical Assembly Tikkun Source Materials Shavuot 5780

Rabbinical Assembly Tikkun Source Materials Shavuot 5780 This packet contains source sheets to accompany both the pre-recorded sessions currently available on YouTube at www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLAUaYjTp5xS5DF06maAV4pbiqlM_tOpxS as well as the live tikkun, beginning on Thursday, May 28th at 9 PM EDT at www.tinyurl.com/RATikkun. Thank you to all of our colleagues who are sharing their Torah to enrich our celebration of Shavuot. Table of Contents Pre-recorded Sessions Moses and Ezekiel: Should Revelation be Hidden or Revealed? ................................................................ 1 Rabbi Abby Sosland Semi-Conscious States of Spirituality .......................................................................................................... 6 Rabbi Danny Nevins The Earthy Jerusalem and the Heavenly Jerusalem: Incident, Imagination and Imperative .................... 9 Rabbi Michael Knopf Theology and Revelation ........................................................................................................................... 16 Rabbi Ahud Sela My Teacher ................................................................................................................................................. 19 Rabbi Ed Bernstein When do we say Shema? You are the real distinction ............................................................................. 24 Rabbi Philip Weintraub How to Hug - Closeness in a Time of Social Distancing: What is Love? .................................................... 27 Rabbi Eric Yanoff -

בס״ד Explanations for the Churban in Tanakh and Chazal Rabbi Judah

בס״ד Explanations for the Churban in Tanakh and Chazal Rabbi Judah Kerbel, Queens Jewish Center צום שבעה עשר בתמוז תשע"ט 1. ויקרא פרק כו, יד-טו (יד) וְִאם לֹא ִת ְשׁ ְמעוּ ִלי וְלֹא ַתֲעשׂוּ ֵאת ָכּל ַה ִמְּצוֹת ָהֵאֶלּה: (טו) וְִאם ְבּ ֻחקַֹּתי ִתּ ְמאָסוּ וְִאם ֶאת ִמ ְשָׁפּ ַטי ִתְּגַעל נְַפ ְשֶׁכם ְלִבְל ִתּי ֲעשׂוֹת ֶאת ָכּל ִמְצ ַוֹתי ְל ַהְפְרֶכם ֶאת ְבִּר ִיתי: 1. Vayikra 26:14-15 But if you do not obey Me and do not observe all these commandments,if you reject My laws and spurn My rules, so that you do not observe all My commandments and you break My covenant... 2. ויקרא פרק כו, כא ֹ (כא) וְִאם ֵתְּלכוּ ִע ִמּי ֶקִרי וְלא תֹאבוּ ִל ְשׁמַֹע ִלי וְיַָסְפ ִתּי ֲעֵל ֶיכם ַמָכּה ֶשַׁבע ְכּ ַחטֹּ ֵאת ֶיכם: 2. Vayikra 26:21 And if you remain hostile toward Me and refuse to obey Me, I will go on smiting you sevenfold for your sins. 3. ויקרא פרק כו, לד-לה (לד) אָז ִתְּרֶצה ָה ֶאָרץ ֶאת ַשְׁבּתֶֹת ָיה כֹּל יְֵמי ֳה ַשׁ ָמּה וְ ֶאַתּם ְבֶּאֶרץ אֹיְֵב ֶיכם אָז ִתּ ְשַׁבּת ָה ֶאָרץ וְִהְרָצת ֶאת ַשְׁבּתֶֹת ָיה: (לה) ָכּל יְֵמי ָה ַשּׁ ָמּה ִתּ ְשׁבֹּת ֵאת ֲא ֶשׁר לֹא ָשְׁב ָתה ְבּ ַשְׁבּתֵֹת ֶיכם ְבּ ִשְׁב ְתֶּכם ָעֶל ָיה: 3. Vayikra 26:34-35 Then shall the land make up for its sabbath years throughout the time that it is desolate and you are in the land of your enemies; then shall the land rest and make up for its sabbath years. -

The Complex Legacy of Debate in Jewish Tradition

UNIT 1 DOES DISPUTE UNITE US OR DIVIDE US? THE COMPLEX LEGACY OF DEBATE IN JEWISH TRADITION I. Two Views of Torah Study 1. Sifrei Deuteronomy, Ha’azinu 321 2. Arukh Hashulhan, Hoshen Mishpat, preface II. Arguing for the Sake of Heaven 3. Pirkei Avot 5:17 4. Rabbi Obadia of Bartinoro’s commentary to Pirkei Avot 5:17 (section 1) 5. Rabbi Jonah ben Abraham Gerondi (“Rabbeinu Yonah”) on Pirkei Avot 5:17 III. The Model of Hillel and Shammai 6. Jerusalem Talmud, Shabbat 1:4 7. Babylonian Talmud, Yevamot 14b 8. Rashi’s Commentary on BT Yevamot 13b 9. Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 13b 10. Babylonian Talmud, Eruvin 13b (continued) IV. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on Dispute 11.Tosefta Hagigah 2:4 12. Maimonides, Commentary on the Mishnah, Introduction to Zeraim 13. Babylonian Talmud, Bava Metzia 84a 14. Rashi’s Commentary on BT Hagigah 3b 15. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, Olat Re’iya DOES DISPUTE UNITE US OR DIVIDE US? I. Two Views of Torah Study 1. Sifrei Deuteronomy, Ha’azinu 321 Halakhic Midrash on Deuteronomy (Land of Israel, 3rd–4th century CE). וְ כֵן הוּא אוֹמֵ ר "הַ כֹּל גִּבּוֹרִ ים עוֹשֵׂ י And Scripture states, “All of them valiant, wagers מִ לְחָמָ ה" (מ"ב כד טז). וְכִי מַ ה גְ ב וּ רָ ה of war” (II Kings 24:16).1 Now what valor can עוֹשִׂ ים בְּ נֵי אָדָ ם הַ הוֹלְכִים בַּ גּוֹלָה? people who are going into exile display? And what וּמַ ה מִ לְחָמָ ה עוֹשִׂ ים בְּ נֵי אָדָ ם זְקוּקִ ים war can people wage when they are fettered in shackles and bound by chains? Rather, “valiant” בְּ זִיקִ ים וְהַ נְּתוּנִים בְּשַׁ לְשְׁ לָאוֹת? אֶ לָּא: refers to those who are valiant in Torah study, as in ִ גּ בּ וֹ רִ י ם — אֵ לּוּ גִבּוֹרֵ י תוֹרָ ה, כְּעִ נְיָן the verse, “Bless the Lord, O you His angels, valiant שֶׁ נֶּאֱמַ ר "בָּרְ כוּ ה' מַ לְאָכָיו גִבּוֹרֵ י כֹּחַ ;(and mighty, who do His word…” (Psalm 103:20 עוֹשֵׂ י דְ בָ רוֹ" (תהלים קג כ). -

The Coiled Serpent of Argument: Reason, Authority, and Law in a Talmudic Tale

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 79 Issue 3 Symposium: "Law &": Philosophical, Psychological, Linguistic, and Biological Article 33 Perspectives on Legal Scholarship October 2004 The Coiled Serpent of Argument: Reason, Authority, and Law in a Talmudic Tale David Luban Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David Luban, The Coiled Serpent of Argument: Reason, Authority, and Law in a Talmudic Tale, 79 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1253 (2004). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol79/iss3/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE COILED SERPENT OF ARGUMENT: REASON, AUTHORITY, AND LAW IN A TALMUDIC TALE DAVID LUBAN* I. THE OVEN OF AKHNAI One of the most celebrated Talmudic parables begins with a re- markably dry legal issue debated among a group of rabbis. A modern reader should think of the rabbis as a collegial court, very much like a secular appellate court, because the purpose of their debate is to gen- erate edicts that will bind the community. The issue under debate concerns the ritual cleanliness of a baked earthenware stove, sliced horizontally into rings and cemented back together with unbaked mortar. Do the laws of purity that apply to uncut stoves apply to this one as well? This stove is the so-called "oven of Akhnai" (oven of serpents). -

ףדה יעושעש אעיצמ אבב Daf Delights Bava Metzia

שעשועי הדף בבא מציעא שעשועי הדף בבא מציעא Daf Delights Bava Metzia Rabbi Zev Reichman 2018/5778 Dedicated to the memory of my chavrusa, friend, mentor, and inspiration מנחם מנדל בן הרב יואל דוד באלק ע’’ה Mr. Mendel Balk, o.b.m. May the Torah learning from this book add to his many merits and bring blessings to his entire family. With deep appreciation and gratitude to Raphael and Linda Benaroya for their leadership, friendship, and support. May the Torah from this work add to the eternal merits of דוד ז״ל בן רפאל ולינדה )יפה( הי״ו David Benaroya יעקב בן רפאל וז׳ולי ז״ל Jacob Benaroya רחל בת יום טוב ורוזה ז״ל Rachel Benaroya תנצב״ה ספר זה מוקדש לעילוי נשמות זקנינו ר' חיים אליהו בן ר' זאב רייכמן ז''ל ר' יחזקאל בן ר' יצחק רפאל הלוי עציון ז''ל מרת מינה נחמה בת הרב ברוך משה נחמיה לאבל ז''ל ר' שמעון בן ר' יצחק הכהן בלוך ז''ל יקירתנו מרת רחל בלוך בת החבר ר׳ אברהם הלוי פרנקל ע״ה ר' משה יצחק בן ר' ישעיהו חיים פייערשטיין ז''ל Dedicated in loving memory of Mr. Jack Diamond o.b.m. by his children Lloyd and Ellen Sokoloff Le’iluy Nishmat Moshe ben Makhlouf ve’Leah and Dov ben Zalman by the Bousbib family Dedicated to the eternal memory of Joseph and Gwendolyn Straus and Jack Gabel by Joyce and Daniel Straus In loving memory of our dear husband, father, and grandfather שאול גרשון בן חיים שמואל ז"ל Dr. Saul G. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages.