Unctad-Icc Investment Guide to Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

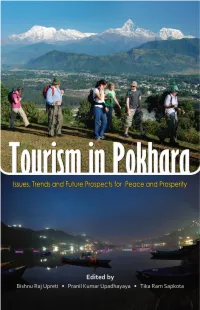

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

![[Final Report]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0363/final-report-90363.webp)

[Final Report]

GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION COMMISSION 2013 FINAL REPORT ON THE ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION OF 9N-ABO TWIN OTTER (DHC6/300) AIRCRAFT OWNED AND OPERATED BY NEPAL AIRLINES CORPORATION AT JOMSOM AIRPORT, MUSTANG DISTRICT, NEPAL ON 16 MAY 2013 [FINAL REPORT] SUBMITTED BY THE COMMISSION FOR THE ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION TO THE GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF CULTURE, TOURISM AND CIVIL AVIATION 18/2/2014 (6/11/ 2070 BS) FINAL REPORT ON THE ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION OF 9N-ABO, TWIN OTTER (DHC-6/300) AIRCRAFT OWNED AND OPERATED BY 2013 NEPAL AIRLINES CORPORATION AT JOMSOM AIRPORT MUSTANG DISTRICT, NEPAL ON 16 MAY 2013 FOREWORD This Final Report on the accident of the Chartered Flight of Nepal Airlines Corporation 9N-ABO, Twin Otter (DHC6/300) aircraft has been prepared by the Aircraft Accident Investigation Commission constituted by the Government of Nepal, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation and Civil Aviation (Accident Investigation) Rules, 2024 B.S. to identify the probable cause of the accident and suggest remedial measures so as to prevent the recurrence of such accidents in future. The Commission carried out thorough investigation and extensive analysis of the available information and evidences, statements and interviews with concerned persons, study of reports, records and documents etc. The Commission had submitted some interim safety recommendations as immediate remedial measures. The Commission in its final report presented safety recommendations to be implemented by the Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal and Nepal Airlines Corporation respectively. -

Market Issue 170.Indd

www.fridayweekly.com.np Every Thursday | ISSUE 170 | RS. 20 SUBSCRIBER COPY | ISSN 2091-1092 22 May 2013 * h]i7 @)&) 9 772091 109009 www.facebook.com/fridayweekly While It Is Spring To keep a packed auditorium silent and the audience glued to their seats is a difficult task. However, the choir group from Kathmandu Chorale managed to do that for nearly two hours at the British School on evening of 4 May. Continued on page 13 Fresh Appeal There is a saying “you are what you eat” and the point has never been clearer than when you brunch at The Yellow House. Tucked under a great jacaranda tree, this bed-and-breakfast makes you feel like you’re transported to another part of the world. Continued on page 18 OMG Fashionalaya OMG Theme Events, an event management company stood up to their reputation as they put up yet another beautiful show at the International Club, Sanepa on 10 May. Continued on page 13 Continued on page 11 event will end with a dance be beneficial to Hamro Khusi, getstarted afterparty with DJ BPM, an INGO registered in the start off with our picks DJ Smiely and DJ Pri. The U.S. as well as to Little Steps participants can drop books, that focuses on the educational clothes or any other items in sectors in rural areas of the the boxes placed at both the country. locations. Together for Positive Change The Footnote The Beneficiaries “We urge all well wishers of While we are busy striving hard to make a better life, let’s go that extra mile The donation granted to EN, this noble cause to connect with and reach out to those who would be grateful to our helping hands. -

Journal of Tourism & Adventure

ISSN 2645-8683 Journal of Tourism & Adventure Vol. 1 No. 1 Year 2018 Editor-in-Chief Prof. Ramesh Raj Kunwar Janapriya Multiple Campus (JMC) (Affi liated to Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal) Aims and scope Journal of Tourism & Adventure (JTA) is an annual double blind peer-reviewed journal launched by the Tribhuvan University, Janapriya Multiple Campus, Pokhara, Nepal. Th is journal welcomes original academic and applied research including multi- and interdisciplinary approaches focusing on various fi elds of tourism and adventure. Th e purpose of this journal is to disseminate the knowledge and ideas of tourism and hospitality in general and adventure in particular to the students, researchers, journalists, policy makers, planners, entrepreneurs and other general readers. It is high time to make this eff ort for tourism innovation and development. It is believed that this knowledge based platform will make the industry and the institutions stronger. Call for papers Th e journal welcomes the following topics: tourism, mountain tourism and mountaineering tourism, risk management, safety and security, tourism and natural disaster, accident, injuries, medicine and rescue, cultural heritage tourism, festival tourism, pilgrimage tourism, rural tourism, village tourism, urban tourism, geo-tourism, paper on extreme adventure tourism activities, ecotourism, environmental tourism, hospitality, event tourism, voluntourism, sustainable tourism, wildlife tourism, dark tourism, nostalgia tourism, tourism planning, destination development, tourism marketing, human resource management, adventure tourism education, tourism and research methodology, guiding profession, tourism, confl ict and peace and remaining other areas of sea, air and land based adventure tourism research. We welcome submissions of research paper on annual bases by the end of June for 2nd issue of this journal onward. -

Hazardous Waste Policy Study for Nepal Project Number: 38401 August 2010

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Hazardous Waste Policy Study for Nepal Project Number: 38401 August 2010 Managing Hazardous Wastes (Financed by the Asian Development Bank Technical Assistance Funding Program) Prepared by Amar B. Manandhar Kathmandu, Nepal For the Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Final Report on Hazardous Waste Policy Study (Nepal) Submitted to Environment Division Ministry of Environment Singh Durbar, Kathmandu Submitted by Amar B. Manandhar Policy Specialist/National Consultant (ADB TA 6361 (REG) – S 16762) 39, Anamnagar, Kathmandu - 32, Nepal P. O. Box - 8973 NPC 410 Telephone: 00 977 1 4228555, Fax: 00 977 1 4238339 Email: [email protected] August 2010 RETA 6361 REG Managing Hazardous Wastes Nepal Hazardous Waste Policy Study Report ABBREVIATIONS % - Percent 0C - Degree Celseus 3R - Three R – Reduce, Reuse and Recycle ADB - Asian Development Bank APO - Asian Productivity Organization CA - Constitutional Assembly CBS - Central Bureau of Statistics CNI - Confederation of Nepalese Industries CP - Cleaner Production Cu. m. - Cubic Meter DOHS - Department of Health Services EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMS - Environmental Management System EPA - Environmental Protection Act EPR - Environmental Protection Regulation ESM - Environmental Standards and Monitoring FNCCI - Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry FNCSI - Federation of Nepalese -

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 88-111 the GAZE JOURNAL of TOURISM and HOSPITALITY

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 88-111 THE GAZE JOURNAL OF TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY Conveying Impetus for Fostering Tourism and Hospitality Entrepreneurship in Touristic Destination: Lessons Learnt from Pokhara, Nepal Niranjan Devkota Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Udaya Raj Paudel Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Udbodh Bhandari Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Article History Abstract Received 24 August 2020 Accepted 10 October 2020 Th is research explores the inter connectedness in entrepreneurs’ and tourists’ perception about western infl uence in business culture of touristic city – Pokhara, Nepal and provides suggestions for fostering sustainable tourism development Keywords of the destination. Primary data results are drawn in which Sustainable researchers have collected 249 data from tourists’ viewpoint, tourism, tourism 395 from determining provincial government roles and 395 entrepreneurship, from hospitality entrepreneurship along with key informants socio-cultural interview with experts’ viewpoints for generating practical identities, role solutions of the existing problems in order to enhance hospitality of government, and tourism business for progress and sustainability. Based on Pokhara, Nepal this triangular data results and secondary resources’ analysis, this research concludes that, for the sustainable tourism business in Pokhara, the entrepreneurs in the area should recognize, preserve, promote and sustain local socio-cultural Corresponding Editor practices; tourists’ viewpoints should be addressed and Ramesh Raj Kunwar [email protected] Gandaki provincial government roles must be constructive. Copyright © 2021 Authors Published by: International School of Tourism and Hotel Management, Kathmandu, Nepal ISSN 2467-933X Devkota/Paudel/ Bhandari: Conveying Impetus for Fostering Tourism and Hospitality.. -

WAIPA-Annual-Report-2004.Pdf

Note The WAIPA Annual Report 2004 has been produced by WAIPA, in cooperation with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). This report was prepared by Vladimir Pankov. Beatrice Abel provided editorial assistance. Teresita Sabico and Farida Negreche provided assistance in formatting the report. WAIPA would like to thank all those who have been involved in the preparation of this report for their various contributions. For further information on WAIPA, please contact the WAIPA Secretariat at the following address: WAIPA Secretariat Palais des Nations, Room E-10061 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (41-22) 907 46 43 Fax: (41-22) 907 01 97 Homepage: http://www.waipa.org UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/2005/3 Copyright @ United Nations, 2005 All rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Page Note 2 Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 Facts about WAIPA 5 WAIPA Map 8 Letter from the President 9 Message from UNCTAD 10 Message from FIAS 11 Overview of Activities 13 The Study Tour Programme 24 WAIPA Elected Office Bearers 25 WAIPA Consultative Committee 27 List of Participants: WAIPA Executive Meeting, Ninth Annual WAIPA Conference and WAIPA Training Workshops 29 Statement of Income and Expenses - 2004 51 WAIPA Directory 55 ANNEX: WAIPA Statute 101 3 Acknowledgements WAIPA would like to thank Ernst & Young – International Location Advisory Services (E&Y–ILAS); IBM Business Consulting Services – Plant Location International (IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI); and OCO Consulting for contributing their time and expertise to the WAIPA Training Programme. Ernst & Young – ILAS IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI OCO Consulting 4 Facts about WAIPA What is WAIPA? The World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA) was established in 1995 and is registered as a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Geneva, Switzerland. -

Nepal Newsletter

News update from Nepal, 1 July 2008 News Update from Nepal 1 July 2008 National Security Nepal is facing the condition of statelessness. On June 22, over 200 Armed Police Force (APF) of Banke revolted to protest against poor ration quality and senior official's ill- treatment. They also beat up APF battalion chief and other senior officers. On June 23, the rebelling armed forces reached an agreement with the government and formed a nine-member team to listen their grievances and corruption done by senior officials. A similar event that took place in Parvat district, however, went unnoticed. On June 20, civil servants urged the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to take strong action against the Minister for Forest and Soil Conservation Matrika Yadav for locking up the Lo- cal Development Officer of Lalitpur, Dandu R. Ghimire, in a toilet for allegedly allowing illegal stone quarries at a community forest in Lalitpur. Frequent robberies in the highways and the rise of extortion, kidnapping and killing by non-state armed actors have weakened the sense of public security. The public life in Bir- gunj has been paralyzed due to the killing of one government official by the cadres of Ta- rai Mukti Tigers. Similarly, in a confrontation between the police and Akhil Tarai Mukti Morcha (ATMM) in Bara four cadres of the latter were killed. A cloth trader was killed in Birgunj while two persons were killed in Butwal. On June 21, Bardibas bazaar remained closed due to the bombing of the petroleum pomp by the cadres of Janatantrik Tarai Mukti Morcha (JTMM). -

Accident Records of Nepalese Registered Helicopters

Accident Records of Nepalese Registered Helicopters Date of A/C Reg. S.N. Type of A/C Operator/Owner Place of Accident Fatality Survival Remarks Accident No. 1 27/12/1979 9N RAE Allutte-III VVIP Langtang 6 0 2 27/04/1993 9N ACK Bell-206 Himalayan Helicopter Langtang 0 Closed operation 3 24/01/1996 9N ADM MI-17 Nepal Airways Sotang 0 3 Closed operation 4 30/09/1997 9N AEC AS-350 Karnali Air Thupten Choling 1 4 Closed operation 5 13/12/1997 9N ADT MI-17 Gorkha Airlines Kalikot 0 Closed operation 6 04/01/1998 9N RAL Bell-206 VVIP Flight Dipayal 7 24/10/1998 9N ACY AS-350B Asian Airlines Mul Khark 3 0 Closed operation Lisunkhu, 8 30/04/1999 9N AEJ AS-350BA Karnali Air 0 Closed operation Sindhupalchowk 9 31/05/1999 9N ADI AS-350B2 Manakamana Airways Ramechhap 0 Closed operation Renamed as Shree 10 11/09/2001 9N ADK MI-17 Air Ananya Mimi 0 5 Airlines 11 12/11/2001 9N AFP AS-350B Fishtail Air Rara Lake, Mugu 4 2 12 12/05/2002 9N AGE AS 350B2 Karnali Air Makalu Base Camp 0 1 Closed operation 13 30/09/2002 9N ACU MI-17 (MI8-MTV) Asian Airlines Sholumkhumbu* 0 None Closed operation 14 28/05/2003 9N ADP MI-17 IV Simrik Air Everest Base Camp 2 6 15 04/01/2005 9N AGG AS-350BA Air Dynasty Heli Service Thhose VDC, Ramechhap 3 None 16 02/06/2005 9N ADN MI-17 Shree Airlines Everest Base Camp. -

The Print Media in Nepal Since 1990: Impressive Growth and Institutional Challenges

THE PRINT MEDIA IN NEPAL SINCE 1990: IMPRESSIVE GROWTH AND INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES Pratyoush Onta The Print Boom Until early 1990, when the king-led Panchayat System gasped for its final breath, the most powerful media in Nepal were all state-owned. The two most important daily newspapers, Gorkhapatra (in Nepali) and The Rising Nepal (in English), were published by Gorkhapatra Sansthan, a ‘corporation’ under government control. Similarly, Radio Nepal and Nepal Television (NTV), both also owned by the state, had complete monopoly over the electronic media. The non-state media was confined to weekly newspapers owned by private individuals, most of whom were affiliated to one or another banned political party.1 Then came the People’s Movement in the spring of 1990, which put an end to absolute monarchy and the Panchayat system. Due to a confluence of several factors, the demise of the Panchayat, of course, being the most significant, media was the one sector which recorded massive growth during the decade of the 1990s – growth seen not only quantitatively but also qualitatively. By the end of 2001, the media scenario was unrecognisable to those who only knew Nepal from the earlier era. And the most dramatic changes came in print and radio. This article deals with the growth in print media, especially the commercial press.2 1 For various aspects of media during the Panchayat years see Baral (1975), Khatri (1976), Royal Press Commission (2038 v.s.), Verma (1988), Wolf et al. (1991), Nepal (2057 v.s.) and Rai (2001). 2 Although the state-owned Radio Nepal continues to be the most powerful media in Nepal with a communication infrastructure unmatched by any other institution, there has been a phenomenal growth in independent FM radio. -

The Guthi System of Nepal

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Tucker, "The Guthi System of Nepal" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3182. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3182 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott Academic Director: Suman Pant Advisors: Suman Pant, Manohari Upadhyaya Vanderbilt University Public Policy Studies South Asia, Nepal, Kathmandu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Nepal: Development and Social Change, SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 and in fulfillment of the Capstone requirement for the Vanderbilt Public Policy Studies Major Abstract The purpose of this research is to understand the role of the guthi system in Nepali society, the relationship of the guthi land tenure system with Newari guthi, and the effect of modern society and technology on the ability of the guthi system to maintain and preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Nepal. -

The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: a Monograph

THE MAOIST INSURGENCY IN NEPAL: A MONOGRAPH CAUSES, IMPACT AND AVENUES OF RESOLUTION Edited by Shambhu Ram Simkhada and Fabio Oliva Foreword by Daniel Warner Geneva, March 2006 Cover Pictures – clockwise from the top: 1) King Gyanendra of Nepal; 2) Madhav Kumar Nepal, leader of the CPN-UML Party; 3) A popular peace rally; 4) Girija Prasad Koirala, President of the Nepali Congress party; 5) The Maoist leadership; 6) The Maoist People’s Liberation Army (PLA); 7) A political rally of the Seven-party Alliance in Kathmandu; 8) Soldiers from Royal Nepal Army (RNA). This publication has been possible thanks to the financial support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Bern, and is part of a larger project on the “Causes of Internal Conflicts and Means to Resolve Them: Nepal a Case Study” mandated and sponsored by the SDC in May 2003. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the PSIO. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means - electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise - without the prior permission of the Institut universitaire de hautes études internationales (HEI) Copyright 2006, IUHEI, CH-Geneva 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS __________________________________________________________________________________ LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.................................................................................. 5 FOREWORD......................................................................................................