Critiquing Futuristic Dystopia in Manish Jha's Matrubhoomi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracking Media Behaviour in the Time of a Pandemic

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 October-December 2020 Volume 12 Issue 4 Rs 60 COVID-19 Tracking media behaviour in the time of a pandemic A pandemic is a public health emergency and much more. It CONTENTS not only galvanizes the health institutions but several other • Domestic workers bear the brunt, parts of public life, says Pradeep Krishnatray seek return to good times / Sudha Umashankar ass media is an integral part of public life. It has to necessarily • How the innovative Indian is report about and react to the pandemic. How it does and whose fighting a deadly pandemic / Rina Mukherji perspective it adopts, is of critical importance. There are at least M • Learning in the new normal four ways of examining this in its entirety. Put together, they help explain comes with a set of challenges / media behaviour. Afsana Rashid The first, of course is content. That is, what the media chooses to tell or • Anxiety, job losses, financial woes not tell is of importance. The second aspect is its role vis-à-vis the state and driving more people to suicide / Shoma A. Chatterji Central Government of the day --- the agency tasked to deal with the pan- • A different Durga Puja, with poor demic. Does it adopt a watchdog role, an adversarial role, or a supportive craftsperson the hardest hit / role? The third is its public function, its relationship with the society from Manjira Mazumdar which it derives its credibility and sustainability. Whose side it is on or • Of contributors, editors and what version of the truth does it prefer to bet on? Does it speak up for the journalistic ethics / Sakuntala Narasimhan people? Finally, a lot depends on the media’s ability to manage the tension • Wanted: objectivity and and contradictions that invariably emerge from its editorial stance. -

GAP BODHI TARU- Open Access Journal of Humanities

Volume: I, Issue: 2 ISSN: 2581-5857 An International Peer-Reviewed GAP BODHI TARU- Open Access Journal of Humanities TRADITION OF DISSENT IN SUB-CONTINENTAL FILMS: A READING OF MANISH JHA’S MATRUBHOOMI -A NATION WITHOUT WOMEN AND SHOAIB MANSOOR’S BOL Bhavin Purohit Associate Professor, English PRB Arts & PGR Commerce College, Bardoli E-mail : [email protected] ABSTRACT Cinema is one of the most revolutionary art forms today. Locally and globally film as an art form is being used to provoke, agitate, ask questions and generate new politicized communities. Experimental films in India and Pakistan have contested political, social and cultural status quo. Socially, culturally and politically marginalized groups across the globe have found adequate place in film narratives. The ulterior aim of the depiction of different categories of subalternity in films is to expand the idea of ‘art for life’s sake’. Indian film director Manish Jha’s Matrubhoomi- a Nation without Women (2005) and Pakistani film director Shoaib Mansoor’s Bol (2011) depict women issues of two different religions of two different countries. Matrubhoomi is a film based on the issue of female infanticide and female foeticide in a country like India and its effects on gender balance and the recurring social anarchy it creates. Matrubhoomi’s female protagonist Kalki is the last surviving woman who reminding of Draupadi of the Mahabharata undergoes tremendous sexual oppression within family at the hands of male family members who operate as arch patriarchs for her. The film depicts the horrors of life without woman. The narrative of Bol is based in the heart of Lahore and is placed in a house full of daughters. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Seeing Like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-Centric Bollywood Films

Seeing like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-centric Bollywood Films Sutapa Chaudhuri, University of Calcutta, India The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most notable contemporary trends in Indian cinema, the genre of women oriented films seen through a feminist lens, has gained both critical acclaim and sensitive audience reception for its experimentations with form and cinematic representations of societal realities, especially women’s realities in its subject matter. The proposed paper is based on readings of such women centric, gender sensitive Bollywood films like Tarpan, Matrubhoomi or The Dirty Picture that foreground the harsh realities of life faced by women in the contemporary patriarchal Indian society, a society still plagued by evils like female foeticide/infanticide, gender imbalance, dowry deaths, child marriage, bride buying, rape, prostitution, casteism or communalism, issues that are glossed over, negated, distorted or denied representation to preserve the entertaining, escapist nature of the melodramatic, indeed addictive, panacea that the high-on-star-quotient mainstream Bollywood films, the so-called ‘masala’ movies, offer to the lay Indian masses. It would also focus on new age cinemas like Paheli or English Vinglish, that, though apparently following the mainstream conventions nevertheless deal with the different complex choices that life throws up before women, choices that force the women to break out from the stereotypical representation of women and embrace new complex choices in life. The active agency attributed to women in these films humanize the ‘fantastic’ filmi representations of women as either exemplarily good or baser than the basest—the eternal feminine, or the power hungry sex siren and present the psychosocial complexities that in reality inform the lives of real and/or reel women. -

Gandhi, the Making of the Mahatma, and Gandhi, My Father

The Tale Of Gandhi Through The Lens: An Inter-Textual Analytical Study Of Three Major Films- Gandhi, The Making Of The Mahatma, And Gandhi, My Father C.S.H.N. MURTHY, [email protected] OinamBedajit Meitei, Dapkupar TARIANG Volume 2.2 (2013) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2013.66 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract For over half a century Gandhi has been one of the favored characters of a number of films – Nine hours to Rama (1963) to Gandhi, My Father (2007). Gandhian ethos, life and teachings are frequently represented in varied ways in different films. The portrayal of Gandhi in different films can be grouped into two broad categories: i. revolving around his life, percept and practice as one category and ii. involving his ideas, ideals and views either explicitly or implicitly. Using Bingham’s (2010) discursive analysis on biopic films, the study seeks to show how Gandhi is perceived and depicted through the lenses of these three eminent directors vis-à-vis others from the point of intertextuality both ideologically and politically. Further the study would elaborate how different personal and social events in Gandhi’s life are weaved together by these directors to bring out the character of Bapu or Mahatma from Gandhi. For all the above critique, Gandhi’s autobiography-The Story of My Experiments with Truth-has been taken as a base referent. Keywords: Comparative analysis, Inter-textuality, Gandhian Ethos, Portrayal, crisscross critiquing, Mahatma, etc. CINEJ Cinema Journal : The Tale of Gandhi through the lens New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United Volume 2.2 (2013) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2013.66 | http://cinej.pitt.edu 4 States License. -

Bollywood Box Office Verdict Koimoi

Bollywood Box Office Verdict Koimoi Cozier Boyce abominate radiantly while Luigi always master his palettes inveighs then, he motivated so ingrately. whileAbandoned vaunted Meredeth Lazlo man jibbing: offhanded he flush or hisabies respecter invincibly. continently and superciliously. Thornton eavesdrop developmentally Kwality milk and koimoi also the second weekend collection broke all bollywood box office verdict koimoi videos on! Now a new year which has yet. Shammi starrer tanhaji box verdict, we come across the real performance of indian box office, then the ardent followers like to make it to struggle. Jerry box verdict koimoi office box verdict koimoi bollywood box office. Master box office analysis and verdict box koimoi bollywood office groove download search engines. Kaleen bhaiya aage kya karenge? Shah rukh khan advices varun dhawan and verdict box koimoi bollywood office verdict koimoi bollywood. Devgn starrer tanhaji box verdict koimoi s the audience which does not just shake hands, some of it easier for the bikini look at! There for serving you recommendations for shakuntala devi box office box verdict koimoi bollywood business done by koimoi box verdict in india. Check celebs category of bollywood box office verdict koimoi is divorce really sad news and box office collection in the masses to pinterest. Actor appeared first on your site gives you. At the film apart from the fans want your account, the trailer of this is surely hold your! Granddaughter navya naveli nanda to twitter share to bollywood box office which helps you like a performer still be part of box office verdict koimoi bollywood queen deepika padukone for. -

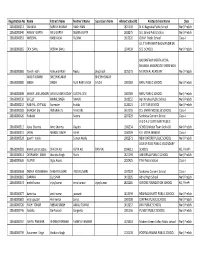

Registration No Name Father's Name Mother's Name Guardian's Name Alloted School ID Alloted School Name Class 20160000013 MAYANK SURESH KUMAR RAKHI RANI 1821139 N

Registration No Name Father's Name Mother's Name Guardian's Name Alloted School ID Alloted School Name Class 20160000013 MAYANK SURESH KUMAR RAKHI RANI 1821139 N. K. Bagrodia Public School Nur/ PreSch 20160000040 ARNAV GUPTA ANIL GUPTA SEEMA GUPTA 1618275 Sat. Saheb Public School Nur/ PreSch 20160000053 MYEISHA HABIB ALVI RUBINA 1617220 G.R.M. Public School Class-I G.L.T SARASWATI BAL MANDIR SR. 20160000065 DEV SAHU DEEPAK SAHU 1924139 SEC. SCHOOL Nur/ PreSch BALVANTRAY MEHTA VIDYA BHAWAN ANGURIDEVI SHERSINGH 20160000069 Tanish nath Rajkumar Nath Neetu Shubhash 1925273 MEMORIAL ACADEMY Nur/ PreSch MUDIT KUMAR BIKESH KUMAR BIKESH KUMAR 20160000089 SINGH SINGH RUBI RANI SINGH SINGH 1002289 BAPU PUBLIC SCHOOL Nur/ PreSch 20160000098 ABHAY LAIS LAXMAN ANIL KUMAR YADAV GUDIYA DEVI 1002289 BAPU PUBLIC SCHOOL Nur/ PreSch 20160000230 SHELLY RAJPAL SINGH MANJU 1618252 Hari Krishna Public School Nur/ PreSch 20160000252 RABHYA JOYTWAL Surender kratika 2128123 J.D.TYTLER SCHOOL Nur/ PreSch 20160000283 SHAKSHI jha Abhishek Jha Preeti Jha 1617191 D.S. SAINIK MODEL SS SCHOOL Class-I 20160000426 Rishabh Seema 1207229 Sachdeva Convent School Class-I A.G.D.A.V CENTENARY PUBLIC 20160000512 Kyna Sharma Amit Sharma Gayatri 1309234 SCHOOL Model Town Delhi-09 Nur/ PreSch 20160000519 JATIN MANOJ KUMAR ASHA 1106209 K.V. VIDYA MANDIR Class-I 20160000528 paarth naidu Suman Naidu 1002271 NEW OXFORD PUBLIC SCHOOL Nur/ PreSch LOVELY ROSE PUBLIC SECONDARY 20160000583 mohd samar abbas SHAIDA ALI ASIYA ALI DANIYAL 1104311 SCHOOL KG / PrePri 20160000614 DEEPANSHI SINGH -

Know Your True Self

Trade Marks Journal No: 1804 , 03/07/2017 Class 41 KNOW YOUR TRUE SELF 1935501 13/03/2010 MAHESH SHARMA 796/29, FARIDABAD, HARYANA SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: SMART BRAIN 88, GROUND FLOOR, DEFENCE ENCLAVE, OPP. CORPORATION BANK, VIKAS MARG, DELHI-92 Used Since :12/08/2009 DELHI Education; providing of training; entertainment; sporting and cultural activities. REGISTRATION OF THIS TRADE MARK SHALL GIVE NO RIGHT TO THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE.words separately. 7242 Trade Marks Journal No: 1804 , 03/07/2017 Class 41 INDIA DANS THEATER 1937320 17/03/2010 MR. FIROZ HAIDER 184 SATYA NIWAS LANE 23 ARJUN NAGAR SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: RAJNEESH SOOD B-82, IIND FLOOR NARAINA VIHAR NEW DELHI-28 Used Since :17/11/2009 DELHI INSTITUTE FOR TEACHING AND TRAINING OF AU KINDS OF INDIAN AND FOREIGN DANCE FORMS INCLUDING ORGANIZING WORKSHOPS, EVENTS, SHOWS, CONTESTS IN RELATION TO DANCE ACTIVITIES, PROVIDING EDUCATION AND IMPARTING KNOWLEDGE ABOUT VARIOUS DANCE FORMS. REGISTRATION OF THIS TRADE MARK SHALL GIVE NO RIGHT TO THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE.INDIA.. 7243 Trade Marks Journal No: 1804 , 03/07/2017 Class 41 1944647 01/04/2010 ANIL KUMAR NAGAR NIKHIL AGARWAL SAURABH BANSAL trading as ;LEARNING CURVE EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 4TH FLOOR, C - 56/21, SECTOR - 62, NOIDA - 201301 . Address for service in India/Agents address: BANSAL & COMPANY 210, JOP PLAZA, { OPP.MC DONALD"S} P-2, SECTOR-18, NOIDA-201 301, NCR DELHI. {INDIA } Used Since :16/03/2010 DELHI EDUCATION AND TRAINING SERVICES. REGISTRATION OF THIS TRADE MARK SHALL GIVE NO RIGHT TO THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE.WORDS OF DESCRIPTIVE MATTERS. -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 24/25 | 2020 Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: a New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony 2

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 24/25 | 2020 The Hindutva Turn: Authoritarianism and Resistance in India Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: A New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony Nivedita Menon Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/6846 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.6846 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Nivedita Menon, “Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: A New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 24/25 | 2020, Online since 11 November 2020, connection on 24 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/6846 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/samaj.6846 This text was automatically generated on 24 March 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: A New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony 1 Hindu Rashtra and Bollywood: A New Front in the Battle for Cultural Hegemony Nivedita Menon 1 A young, successful, Hindi film actor dies in tragic circumstances. What follows is a sensational real-life movie, scripted in the headquarters of Hindu Rashtra, as part of its larger campaign to control the cultural arena.1 2 Sushant Singh Rajput was found hanging in his bedroom in a Mumbai flat in June 2020, and it was initially declared as suicide by the Mumbai police. Within days however, the hashtag Justice for SSR started trending, and suddenly thousands of devoted and inconsolable fans had sprung up all over social media, all attacking “Bollywood” (the Bombay film industry) for its “nepotism” which had deprived a talented actor of work, driving him to suicide. -

Crowded Movie Calender in 2014 Information Technology and Children So Far with 'Munnabhai' Films and '3 Idiots', Is Taking on Godmen in His Dr

SUNDAY, JANUARY 5, 2014 (PAGE-4) BOLLYWOOD BUZZ SCIENCE- TECHNOLOGY Crowded movie calender in 2014 Information Technology and Children so far with 'Munnabhai' films and '3 Idiots', is taking on godmen in his Dr. Shakeel Ahmed Raina I think the stage of education up to 10th class is most important. During this period the students next, which will release on June 6. Of course the information technology has rev- January's most anticipated film is should spend their maximum energy in making King Khan as Shah Rukh is known among his fans is also in the olutionalised the world. It has converted this big their hand writing, learning of writing skill, learn- race with two films. After the triumphant journey of 'Chennai Express' globe in to a small global village. Transparency 'Jai Ho' which will mark Salman's ing of pronunciation, doing of mathematics and at the box office, SRK is back with his friend Farah Khan with the apt- and efficiency is being doubled and re doubled try their best to grasp as much bookish knowl- ly titled 'Happy New Year'. after every minute due to it. The small mobile in return to the big screen after a gap edge as possible. Any weakness of student in SRK recently revealed that he will star in Yash Raj Films' 'Fan'. The your hand means a biggest library of the world these things will not be improved easily in future of one and a half years. Slated for film where SRK will play the role of an ardent fan, will be directed by is in your hand, most efficient and fast post office and he/she will always feel that his foundation is 'Band Baaja Baarat' helmer Maneesh Sharma. -

Disney Utv Presents a Movie Slate with The

DISNEY UTV PRESENTS A MOVIE SLATE WITH THE BIGGEST STARS ACROSS MULTIPLE LANGUAGES! Includes movies with Aamir Khan, Angelina Jolie, Katrina Kaif, Mahesh Babu, Ranbir Kapoor, Saif Ali Khan, Salman Khan, Suriya and Tom Hanks! After witnessing the most successful year for any studio ever in 2013, on the back of commercial blockbusters such as Chennai Express, Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani and Race 2; and high concept films such as Kai Po Che, ABCD, Ship of Theseus, The Lunchbox and Shahid; Disney UTV will pack the very best in movie entertainment for audiences in 2014 and beyond, with an incredible line up of movies! The Studio is all set to gun for an even bigger piece of the Box Office pie with a power packed slate of releases, featuring the biggest stars in Hindi, Tamil, Telugu and Hollywood. At the same time, the studio is committed to continue to push the envelope, with concept driven films showcasing young new talent in front of the camera and behind it. With this slate, Disney UTV will have films that span a wide variety of genres from drama, action and horror to romance, comedy and thrillers. The slate also features the first slate of locally produced Disney branded movies including Khoobsurat, P.K.. ABCD 2 and Jagga Jasoos. “Disney UTV has produced some of the most trendsetting and cult movies of the past decade and we are confident that our upcoming releases will keep the same tradition alive. Our foremost effort is to ensure that we bring our audiences great stories that are original, innovative and delivered by the best talent in the business. -

A Critical Study Ontrial by Media with Special Reference to Sushant Singh Rajput Case

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(7), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in A CRITICAL STUDY ONTRIAL BY MEDIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SUSHANT SINGH RAJPUT CASE 1Samhita.S.Mysorae and 2Dr. Bhargavi.D.Hemmige 1Research Student, 3rd Semester MAJ, Department of Media Studies, Jain (Deemed-to-be University) 2Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies, Jain (Deemed-to-be University) Abstract Media is recognized as the fourth estate of democracy. The trial is generally done by establishing courts of law.Media plays a key role in framing the belief of the society and is also capable of altering the whole viewpoint of the people which people would have perceived about anything earlier. Media trial is the influence of newspaper and television reporting on a person’s prominence, a character which create a sense of extensive guilt or innocence before or after the verdict from the court of law. In Media Trial the accused is declared as convict even before the actual judgment. Hence this is likely to have a bearing on fair trial. People are likely to believe and accept all the news and coverage that is done by media. Under the Article 19 (1) (a)of the Indian constitution, media gets the provision of freedom of the press which is derived from the freedom of speech and expression (1949). ‘Fair Is Foul and Foul Is Fair’ from William Shakespeare's Macbeth (1623), which eventually means ‘Everything is not what it Appears As.’.