GAP BODHI TARU- Open Access Journal of Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Withheld File 2020 Dividend D-8.Xlsx

LOTTE CHEMICAL PAKISTAN LIMITED FINAL DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 @7.5% RSBOOK CLOSURE FROM 14‐APR‐21 TO 21‐APR‐21 S. NO WARRANT NO FOLIO NO NAME NET AMOUNT PAID STATUS REASON 1 8000001 36074 MR NOOR MUHAMMAD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 2 8000002 47525 MS ARAMITA PRECY D'SOUZA 927 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 3 8000003 87080 CITIBANK N.A. HONG KONG 382 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 4 8000004 87092 W I CARR (FAR EAST) LTD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 5 8000005 87094 GOVETT ORIENTAL INVESTMENT TRUST 1,530 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 6 8000006 87099 MORGAN STANLEY TRUST CO 976 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 7 8000007 87102 EMERGING MARKETS INVESTMENT FUND 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 8 8000008 87141 STATE STREET BANK & TRUST CO. USA 1,626 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 9 8000009 87147 BANKERS TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 10 8000010 87166 MORGAN STANLEY BANK LUXEMBOURG 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 11 8000011 87228 EMERGING MARKETS TRUST 58 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 12 8000012 87231 BOSTON SAFE DEPOSIT & TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 13 8000017 6 MR HABIB HAJI ABBA 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 14 8000018 8 MISS HISSA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 15 8000019 9 MISS LULU HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 16 8000020 10 MR MOHAMMAD ABBAS 18 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 17 8000021 11 MR MEMON SIKANDAR HAJI ABBAS 12 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 18 8000022 12 MISS NAHIDA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 19 8000023 13 SAHIBZADI GHULAM SADIQUAH ABBASI 792 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 20 8000024 14 SAHIBZADI SHAFIQUAH ABBASI -

Trends of Pakistani Films: an Analytical Study of Restoration of Cinema

Trends of Pakistani films: An analytical study of restoration of cinema Fouzia Naz* Sadia Mehmood** ABSTRACT People prefer to go to the cinema as compared to theaters because of its way of execution and performance. Background music, sound effects, lights, direction attract people, and its demonstrations relate people to their lives. It is true that films have a unique and powerful connection between human behavior and societal culture. Pakistani film industry faced the downfall and now it is doing its best to make the films on international standards. In this research article, the background of Pakistani cinema and causes of downfall will be discussed. The main idea of this research article is to identify and study the development of Pakistani film industry. Qualitative and quantitative data collection will be used as the research method of this research. This research article helps in observing different mass media theory based on Pakistani cinema. Moreover, it will be explained what filmmakers critiques and people say regarding revival or restoration. Keywords: downfall, revival, the impact of the Pakistani film industry, Lollywood *Assistant professor, Mass Communication, University of Karachi) **Assistant professor, Mass Communication, University of Karachi) 33 Jhss, Vol. 8, No. 2 , July to December, 2017 The definition of cinema can be explained as “another word of moving a picture”1This is the place where films are shown to the public. Most of the people who are not into the arts get confused in cinema and theater. The theater is the building where live performance is performed2. The similarity between cinema and theaters are both of them execute act and created for public entertainment. -

The Role of Translation in the Resurgence of Pakistani Dramas

International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) ISSN 2307-4531 (Print & Online) http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Role of Translation in the Resurgence of Pakistani Dramas Aisha Shoukat* (B.Ed., MA English) Email: [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this research is to investigate the role of translation in the resurgence of Pakistani Drama Industry, as well as to present suggestions and recommendations for the translators to come up the hurdles they face while translating the dramas. The data was collected through survey technique. Questionnaire were distributed among randomly selected participants comprising open ended and close ended questions. At the end of survey the participants were given 3 images to read and give their views regarding the need of translating Pakistani dramas. 40 participants were randomly selected from English department of The University of Lahore, Different cities of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Through findings, the research revealed the revival of Pakistani drama industry and the need of translation for the resurgence of the industry in a foreign country. The findings also shows the interest of the foreigners in Pakistani dramas. The study is important for the readers as it would act as a platform for future researchers to explore the new dimensions in literary translation. Keywords: Pakistani dramas; translation; revival; international audience. 1. Introduction Translation is a mean of communication which help us to communicate with others in the world around. It is defined as “The communication of meaning from one language (the source) to another language (the target) ”[16]. The main focus of the study is on the Literary Translation as it is a challenging phenomenon. -

Supreme Ishq Download Mp3

Supreme ishq download mp3 Download Supreme Ishq Songs Pakistani Artists Mp3 Songs, Supreme Ishq Mp3 Songs Zip file. Free High quality Mp3 Songs Download Kbps. Bus Ishq Mohabbat Apna Pan - Supreme Ishq. Genre: Supreme Ishq, The Concert Hall. times, 0 Play. Download. Supreme Ishq - Tere Ishq Nachaya (Riaz Ali Qadri). Genre: Supreme, Rehan Nagra. times, 0 Play. Download. Tere Ishq Nachaya Full Song Abida Parveen. Genre: sufi, Folk & Sufi by Zohaib. times, 0 Play. Download. Tere Ishq Nachaya - Supreme Ishq. Download Supreme Ishq (Anarkali) Array Full Mp3 Songs By Various Movie - Album Released On 16 Mar, in Category Hindi - Mr-Jatt. Download Supreme Ishq (Anarkali) Hindi Album Mp3 Songs By Various Artists Here In Full Length. Tere Ishq Nachaya - Supreme Ishq | Love2Pak - Listen and Download mp3 Songs, A big resource to listen and download Lollywood mp3 songs, Bollywood mp3. supreme ishq mp3 free Download Link ?keyword=supreme-ishq-mpfree&charset=utf and Noor Jehan from the movie Supreme Ishq Anarkali. Download the Supreme Ishq Anarkali song online at Play MP3 now! Supreme Ishaq(Ishq Muhabbat apna pan by SHABNAM MAJEED) Shoaib mansoor's production LIVE mp3 kbps. Download | Play. Supreme ISHQ SONG. Singers: Shabnam Majeed, Jawaid Ali Khan Lyrics & Music: Shoaib Mansoor Music Arrangement: Khawar. Supreme Ishq - Tere Ishq Nachaya (Riaz Ali Qadri) Various Supreme Ishq - Tere Ishq Nachaya (Riaz Ali Qadri) Free Download. 80 Views(). Listen to the Gharoli song by Abida Parveen from the movie Supreme Ishq. Download the Gharoli song online at Play MP3 now! Yaar Dhaadi song by Mohammad Jaman from the movie Supreme Ishq. Download the Yaar Dhaadi song online at Play MP3 now! hope u like this sufi song. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Analisis Semiotik Terhadap Film in the Name of God

ANALISIS SEMIOTIK TERHADAP FILM IN THE NAME OF GOD Skripsi Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Komunikasi Islam (S. Kom. I) Oleh Hani Taqiyya NIM: 107051002739 JURUSAN KOMUNIKASI DAN PENYIARAN ISLAM FAKULTAS ILMU DAKWAH DAN ILMU KOMUNIKASI UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2011 M/1432 H LEMBAR PERNYATAAN Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa: 1. Skripsi ini merupakan hasil karya asli saya yang diajukan untuk memenuhi salah satu penyataan memperoleh gelar strata 1 di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 2. Semua sumber yang saya gunakan dalam penulisan ini telah saya cantumkan sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 3. Jika di kemudian hari terbukti bahwa karya ini bukan hasil karya asli saya atau merupakan hasil jiplakan dari karya orang lain, maka saya bersedia menerima sanksi yang berlaku di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. Ciputat, Mei 2011 Hani Taqiyya ABSTRAK Hani Taqiyya Analisis Semiotik Terhadap Film In The Name of God Pasca kejadian Serangan 11 September 2001 lalu, wajah dunia Islam kian menjadi sorotan. Gencarnya media-media yang mengatakan bahwa otak serangan itu adalah teroris muslim, membawa khalayak kepada konstruksi identitas agama Islam sebagai agama yang penuh dengan kekerasan dan radikalisme. Apalagi setelah beberapa serangan lain yang mengatasnamakan perbuatan tersebut sebagai perbuatan jihad, karena dilakukan atas nama Allah SWT dan untuk menegakkan agama Islam. Sehingga, tidak kata yang lebih populer menyimbolkan kekerasan dan teror atas nama Islam di atas selain jihad, padahal konsep jihad yang seperti itu tidak sesuai dengan agama Islam yang rahmatan lil ‟alamin. Bukan hanya media cetak saja, film sebagai salah satu media massa juga menggambarkan hal tersebut dengan cara yang berbeda. -

Film in Südasien Nadja-Christina Schneider (Hg.)

Südasien-Informationen Nr. 14 Februar 2008 Film in Südasien Nadja-Christina Schneider (Hg.) Südasien-Informationsnetz e.V. Reichenberger Straße 35 D - 10999 Berlin Tel.: 030 – 788 95 411 Fax: 030 – 788 95 253 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.suedasien.info Spendenkonto: Konto 7170695008 Berliner Volksbank BLZ: 100 900 00 ISSN 1860 - 0212 Inhalt Editorial von Nadja-Christina Schneider.............................................................................................................. 3 Einheit in der cineastischen Vielfalt Oder: gibt es „das“ indische Kino? von Nadja-Christina Schneider.............................................................................................................. 5 Kino als Agens sozialen Wandels: Indische Filmregisseure im antikolonialen Umbruch (1935-47) von Annemarie Hafner........................................................................................................................ 10 Die Frau im kommerziellen Hindi-Kino: Symbol indischer Tradition und Kultur von Ariane Jayasuriya ......................................................................................................................... 16 Die Ausbürgerung Einheimischer und die Einbürgerung von Ausländern: Der Hindu-Nationalismus und das Revival des Hindi-Kinos in den 1990er Jahren von Radhika Desai ............................................................................................................................. 21 Wo der Khan nicht regiert: Muslime im indischen Film – Muslime in Bollywoods Filmindustrie -

Seeing Like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-Centric Bollywood Films

Seeing like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-centric Bollywood Films Sutapa Chaudhuri, University of Calcutta, India The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most notable contemporary trends in Indian cinema, the genre of women oriented films seen through a feminist lens, has gained both critical acclaim and sensitive audience reception for its experimentations with form and cinematic representations of societal realities, especially women’s realities in its subject matter. The proposed paper is based on readings of such women centric, gender sensitive Bollywood films like Tarpan, Matrubhoomi or The Dirty Picture that foreground the harsh realities of life faced by women in the contemporary patriarchal Indian society, a society still plagued by evils like female foeticide/infanticide, gender imbalance, dowry deaths, child marriage, bride buying, rape, prostitution, casteism or communalism, issues that are glossed over, negated, distorted or denied representation to preserve the entertaining, escapist nature of the melodramatic, indeed addictive, panacea that the high-on-star-quotient mainstream Bollywood films, the so-called ‘masala’ movies, offer to the lay Indian masses. It would also focus on new age cinemas like Paheli or English Vinglish, that, though apparently following the mainstream conventions nevertheless deal with the different complex choices that life throws up before women, choices that force the women to break out from the stereotypical representation of women and embrace new complex choices in life. The active agency attributed to women in these films humanize the ‘fantastic’ filmi representations of women as either exemplarily good or baser than the basest—the eternal feminine, or the power hungry sex siren and present the psychosocial complexities that in reality inform the lives of real and/or reel women. -

UNIVERSITY of KARACHI CONFUCIUS INSTITUTE CERTIFICATE COURSE in CHINESE LANGUAGE ADMISSIONS 2017 LIST of SELECTED CANDIDATES Dated: 29-07-2017 S

UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI CONFUCIUS INSTITUTE CERTIFICATE COURSE IN CHINESE LANGUAGE ADMISSIONS 2017 LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES Dated: 29-07-2017 S. FORM ACD. NAME FATHER'S NAME LEVEL SHIFT No. No. % 1 502 SHEHARYAR ALI ANSARI IRSHAD ALI ANSARI 57.36 Level-I Morning 2 503 KHURRAM AHMED PASHA RAIS AHMED PASHA 52.82 BC Weekend 3 507 JAVAID ISLAM BHATTI SHAMS UL ISLAM BHATTI 63.82 BC Weekend 4 511 OBAID IQBAL IQBAL AHMED 64.31 Level-I Weekend 5 512 MUHAMMAD BILAL SHABBIR HUSSAIN 50.55 Level-I Weekend 6 514 MUHAMMAD JANSHER PERVEZ MUHAMMAD PERVEZ 51.91 Level-I Morning 7 516 ALI IQBAL SHAHID IQBAL 45.45 Level-I Weekend 8 518 IKHLAQ HUSSAIN MIRZA HUSSAIN 73.91 Level-I Morning 9 519 ALI ABBAS MUHAMMAD ALI 73.91 Level-I Afternoon 10 526 SYED AL E HASSAN RIZVI SYED IZHAR HUSSAIN RIZVI 58.64 Level-I Morning 11 534 MUHAMMAD HAMMAD MUHAMMAD ISHAQ 54.42 Level-I Morning 12 544 MUHAMMAD SHABAN SUNASRA NASEEM HAIDER 72.55 Level-I Weekend 13 545 ZULFIQAR ALI BARKAT ALI 55.64 Level-I Weekend 14 548 SEHRISH KHAN M, IQBAL 58.00 Level-I Morning 15 549 ANSA JABBAR ABDUL JABBAR 54.36 Level-I Afternoon 16 552 DANISH MAHMOOD MAHMOOD RAZA 57.91 Level-I Afternoon 17 553 ARIFA SOHAIL SOHAIL SHEHZAD 59.64 Level-I Morning 18 558 EMAAD UDDIN SIDDIQUI MUMTAZ UDDIN SIDDIQUI 61.27 BC Weekend 19 559 MUHAMMAD AWAIS MIR AZAM 69.86 Level-I Afternoon 20 562 MEHWISH ZAFAR ZAFAR AKHTER 56.09 Level-I Morning 21 563 MARYAM ZAFAR ZAFAR AKHTAR 65.00 BC Weekend 22 564 HAMZA BIN NASIR MUHAMMAD NASIR AWAN 52.27 BC Weekend 23 567 SANA MUHAMMAD HAROON 50.00 Level-I Weekend 24 568 SALMAN -

Roll No Name of Student Urdu Math Eng S.Stud Isl/ME G.Sci Total

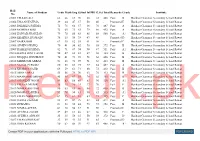

Roll Name of Student Urdu Math Eng S.Stud Isl/ME G.Sci Total Remarks Grade Institute No 21001 EMAAN ALI 66 66 63 70 80 63 408 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21002 EMAAN FATIMA 39 24 47 37 50 40 - Promoted E Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21003 PAKEEZA FATIMA 72 78 66 87 86 78 467 Pass A Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21004 MOMINA BIBI 72 65 73 63 79 80 432 Pass A Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21005 ZAINAB SHAHZAD 79 75 85 88 85 88 500 Pass A1 Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21006 KHADIJA HUSSAIN 36 15 58 39 43 49 - Promoted D Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21007 SAIRA BIBI 67 15 62 55 61 60 - Promoted C Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21008 AIMEN SHAFIQ 70 41 58 62 76 65 372 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21009 RAHEEN FATIMA 82 71 87 94 90 87 511 Pass A1 Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21010 HADIA BINTE ASIM 58 47 62 61 67 68 363 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21011 RUQQIA SHAHZADI 76 41 71 78 78 62 406 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21012 MEHROSH ABBAS 51 68 76 79 71 68 413 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21013 SAJJAL PERVAIZ 80 58 83 75 77 84 457 Pass A Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21014 KHADIJA SAJID 69 59 61 71 80 73 413 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21015 ARFA MIRAJ 55 56 79 70 83 70 413 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21016 MAHNOOR IMRAN 45 58 67 55 78 62 365 Pass B Honhaar Grammar Secondary School Rawat 21017 SHANZAY NOOR 89 83 88 85 85 90 520 Pass A1 Honhaar Grammar -

Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across the Border: the Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Winter 3-19-2018 Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry Dina Khdair DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Khdair, Dina, "Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry" (2018). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 31. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZING PAKISTANI IDENTITY ACROSS THE BORDER: THE POLITICS OF CROSSOVER STARDOM IN THE HINDI FILM INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION In 2010, Pakistani musician and actor Ali Zafar noted how “films and music are one of the greatest tools of bringing in peace and harmony between India and Pakistan. As both countries share a common passion – films and music can bridge the difference between the two.”1 In a more recent interview from May 2016, Zafar reflects on the unprecedented success of his career in India, celebrating his work in cinema as groundbreaking and forecasting a bright future for Indo-Pak collaborations in entertainment and culture.2 His optimism is signaled by a wish to reach an even larger global fan base, as he mentions his dream of working in Hollywood and joining other Indian émigré stars like Priyanka Chopra. -

Written Test for the Posts of Veterinary Officer, 2016

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF VETERINARY OFFICER, 2016. NOTICE On post conduct review of the paper, it has been found out that Answer Key of 02 questions of written test for Veterinary Officer held on 24-12-2016 were inadvertently wrongly entered. The Commission reviewed the matter and decided to grant credit of two marks across the board. The revised list of the following 477 candidates (including 390 Candidates already cleared for interview) for recruitment to (126) POSTS OF VETERINARY OFFICER (BS-17) (HEALTH/DAIRY/RESEARCH/ PVTV(ABAD)/PRODUCTION/ LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION OFFICER) ON REGULAR BASIS (INCLUDING 04 POSTS RESERVED FOR DISABLED QUOTA, 06 POSTS FOR MINORITY QUOTA AND19 POSTS FOR WOMEN QUOTA) IN THE PUNJAB LIVESTOCK & DAIRY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT, 2016 is posted on PPSC Website. 2. Call up letters to the candidates for Interview (excluding those already interviewed) will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC very soon. They will also be informed through SMS and Email. 3. The candidates will be interviewed, if they are found eligible at the time of Interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring academic certificates and related documents at the time of Interview as being intimated to them through PPSC Website (Instructions for the Candidates), SMS and Email shortly. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10003 97800471 ALIHA NISAR NISAR JAMIL 2 10012 97800636 AROOSA SAQIB MUHAMMAD