Documenting Racism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

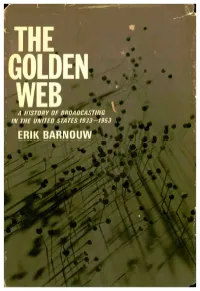

The-Golden-Web-Barnouw.Pdf

THE GOLDEN WE; A HISTORY OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED STA TES 1933-195 r_ ERIK BARNOUW s 11*. !,f THE GOLDEN WEB A History of Broadcasting in the United States Volume II, 1933 -1953 ERIK BARNOUW The giant broadcasting networks are the "golden web" of the title of this continuation of Mr. Bamouw's definitive history of Amer- ican broadcasting. By 1933, when the vol- ume opens, the National Broadcasting Com- pany was established as a country -wide network, and the Columbia Broadcasting System was beginning to challenge it. By 1953, at the volume's close, a new giant, television, had begun to dominate the in- dustry, a business colossus. Mr. Barnouw vividly evokes an era during which radio touched almost every Ameri- can's life: when Franklin D. Roosevelt's "fireside chats" helped the nation pull through the Depression and unite for World War II; other political voices -Mayor La Guardia, Pappy O'Daniel, Father Coughlin, Huey Long -were heard in the land; and overseas news -broadcasting hit its stride with on-the -scene reports of Vienna's fall and the Munich Crisis. The author's descrip- tion of the growth of news broadcasting, through the influence of correspondents like Edward R. Murrow, H. V. Kaltenborn, William L. Shirer, and Eric Sevareid, is particularly illuminating. Here are behind- the -scenes struggles for power -the higher the stakes the more im- placable- between such giants of the radio world as David Sarnoff and William S. Paley; the growing stranglehold of the ad- vertising agencies on radio programming; and the full story of Edwin Armstrong's suit against RCA over FM, with its tragic after- math. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

TELEVISION and VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997: a Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1

ISBN: 0-8444-0946-4 [Note: This is a PDF version of the report, converted from an ASCII text version. It lacks footnote text and some of the tables. For more information, please contact Steve Leggett via email at "[email protected]"] TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1 October 1997 REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS TELEVISION AND VIDEO PRESERVATION 1997 A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation Volume 1: Report Library of Congress Washington, D.C. October 1997 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Television and video preservation 1997: A report on the current state of American television and video preservation: report of the Librarian of Congress. p. cm. þThis report was written by William T. Murphy, assigned to the Library of Congress under an inter-agency agreement with the National Archives and Records Administration, effective October 1, 1995 to November 15, 1996"--T.p. verso. þSeptember 1997." Contents: v. 1. Report - ISBN 0-8444-0946-4 1. Television film--Preservation--United States. 2. Video tapes--Preservation--United States. I. Murphy, William Thomas II. Library of Congress. TR886.3 .T45 1997 778.59'7'0973--dc 21 97-31530 CIP Table of Contents List of Figures . Acknowledgements. Preface by James H. Billington, The Librarian of Congress . Executive Summary . 1. Introduction A. Origins of Study . B. Scope of Study . C. Fact-finding Process . D. Urgency. E. Earlier Efforts to Preserve Television . F. Major Issues . 2. The Materials and Their Preservation Needs A. -

The Evolution of Racism Through the Lens of Lynching Rhetoric and Memory

THE EVOLUTION OF RACISM THROUGH THE LENS OF LYNCHING RHETORIC AND MEMORY by TAMMY BLUE ANDREW BAER, COMMITTEE CHAIR HARRIET AMOS DOSS PAMELA STERNE KING A THESIS Submitted to the graduate faculty of The University of Alabama at Birmingham, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of History BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 2020 ProQuest Number:27833348 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 27833348 Published by ProQuest LLC (2020). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All Rights Reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 THE EVOLUTION OF RACISM THROUGH THE LENS OF LYNCHING RHETORIC AND MEMORY TAMMY BLUE HISTORY ABSTRACT The Evolution of Racism Through the Lens of Lynching Rhetoric and Memory, examines the use of ‘lynching’ in its definition, legislation and politics. Rhetoric has the power to influence and persuade, therefore when public figures manipulate lynching rhetoric, the meaning of lynching becomes distorted. In part, this thesis explores the difficulty of defining lynching. Among others, key players in this process included Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Monroe Work of the Tuskegee Institute, and Jessie Daniel Ames of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL). -

Web Du Bois E a Revista the Crisis, 1910-1920

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA SOCIAL CARLOS ALEXANDRE DA SILVA NASCIMENTO REPRESENTANDO O “NOVO” NEGRO NORTE-AMERICANO: W. E. B. DU BOIS E A REVISTA THE CRISIS, 1910-1920 São Paulo 2015 CARLOS ALEXANDRE DA SILVA NASCIMENTO REPRESENTANDO O “NOVO” NEGRO NORTE-AMERICANO: W. E. B. DU BOIS E A REVISTA THE CRISIS, 1910-1920 Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Robert Sean Purdy São Paulo 2015 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Nascimento, Carlos Alexandre da Silva Nascimento N244r Representando o "novo" negro norte-americano: W. E. B. Du Bois e a revista The Crisis, 1910-1920 / Carlos Alexandre da Silva Nascimento Nascimento ; orientador Robert Sean Purdy Purdy. - São Paulo, 2015. 233 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)- Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de História. Área de concentração: História Social. 1. História dos Estados Unidos . 2. Direitos Civis. 3. Afro-americano. 4. Representação. 5. W. E. B. Du Bois. I. Purdy, Robert Sean Purdy, orient. II. Título. NASCIMENTO, Carlos Alexandre da Silva. Representando o “novo” negro norte-americano Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em História. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90d94068 Author Evans, Taylor Scott Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Taylor Scott Evans December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Mark Minch-de Leon Mr. John Jennings, MFA Copyright by Taylor Scott Evans 2018 The Dissertation of Taylor Scott Evans is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Whenever I was struck with a particularly bad case of “You Should Be Writing,” I would imagine the acknowledgements section as a kind of sweet reward, a place where I can finally thank all the people who made every part of this project possible. Then I tried to write it. Turns out this isn’t a reward so much as my own personal Good Place torture, full of desire to acknowledge and yet bereft of the words to do justice to the task. Pride of place must go to Sherryl Vint, the committee member who lived, as it were. She has stuck through this project from the very beginning as other members came and went, providing invaluable feedback, advice, and provocation in ways it is impossible to cite or fully understand. -

Mamie Kirkland, Witness to an Era of Racial Terror, Dies at 111 - the New York Times

1/11/2020 Mamie Kirkland, Witness to an Era of Racial Terror, Dies at 111 - The New York Times https://nyti.ms/36Gpj14 Mamie Kirkland, Witness to an Era of Racial Terror, Dies at 111 She endured the horrors of the African-American experience — lynchings, riots, the Ku Klux Klan — and worked to ensure that they never slipped from collective memory. By Dan Barry Published Jan. 9, 2020 Updated Jan. 10, 2020 Mamie Lang Kirkland died last month at her home in upstate New York. She was the mother of nine, the matriarch of another 158, a longtime saleswoman for Avon Products, and, at the time of her death, at 111, the oldest resident of Buffalo. That only begins to describe Ms. Kirkland. She was also the embodiment of the African-American experience of the 20th century, her life’s long journey altered repeatedly by the racial violence and bigotry coursing through the United States. Lynchings, riots, the Ku Klux Klan — she survived it all, and spent her centenarian years working to ensure that these realities never slipped from collective memory. Her life helped inspire the creation, in 2018, of the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Ala. Both document the country’s history of racial terrorism and encourage social justice. Ms. Kirkland figures in two of the exhibits, said Sia Sanneh, a senior attorney with the Equal Justice Initiative, the nonprofit that started the memorials. “Her life was such an inspiration to us,” Ms. Sanneh said. “It embodied all those things.” Mamie Lang was born on Sept. -

Groping in the Dark : an Early History of WHAS Radio

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2012 Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio. William A. Cummings 1982- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cummings, William A. 1982-, "Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 298. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/298 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A. University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2012 Copyright 2012 by William A. Cummings All Rights Reserved GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A., University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Approved on April 5, 2012 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Christine Ehrick Kyle Barnett ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Horace Nobles. -

Charles Seeger's Theories on Music and Class Structure

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt VISIONS OF A “MUSICAL AMERICA” IN THE RADIO AGE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Faculty of Arts and Sciences by Stephen R. Greene This dissertation was presented B. Mus., Westminster Choir College, 1976 M. Mus., Universityby of Oklahoma, 1990 Stephen R. Greene It was defended on SubmittedApril to the 30, Graduate 2008 Faculty of the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Stephen R. Greene It was defended on April 30, 2008 and approved by Don O. Franklin, Ph.D., Professor of Music Mary S. Lewis, Ph.D., Professor of Music Bell Yung, Ph.D., Professor of Music Ronald J. Zboray, Ph.D., Professor of Communication Dissertation Advisor: Deane L. Root, Ph.D., Professor of Music ii Copyright © by Stephen R. Greene 2008 iii VISIONS OF A “MUSICAL AMERICA” IN THE RADIO AGE Stephen R. Greene, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2008 In the United States during the 1920s and 1930s a loose-knit group of activists promoting what they called good music encountered the rise of commercial radio. Recognizing a tremendous resource, they sought to enlist radio in their cause, and in many ways were successful. However, commercial radio also transformed the activists, subverting an important part of their vision of a musical America: widespread preference for good music in the public at large. -

Judge Lynch S Cause Cel Bre Fr Ank — Or ( B ) the Mob Was Or Der Ly New Leans Mafia

JUDGELYNCH HIS FIRS T HU N D RED Y EARS BY FRANK SHAY NEWY ORK WASHBU RN IN C. IVES , By th e Same Auth or IRON MEN AN D WOODEN SHIPS MY PIOUS FRIENDS AN D DRUNKEN COMPANIONS ’ HERE S AUDACITY# INCREDIB LE PI#ARRO PIRATE WENCH etc . etc. , JUDGELYNCH HIS FIRS T HU N D RED Y EARS BY FRAN K SHAY N EWY ORK WASHBU RN IN C. IVES , CO IG H 1 8 B Y K H PYR T, 93 , FRAN S AY All rights r eserved P R I N T E D I N T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S O F A M E R I C A - B Y T H E VA I L B A L L O U P RE S S , I N C . , B I N G H A MT O N , N . Y . Carrter m Preface “ TO HELL WITH THE LAW Chapter One THERE WAS A JUDGE NAMED LYNCH Chapter Two THE EARLY LIFE AN D TIMES OF JUDG E LYNCH Chapter Three ’ JUDG E LYNCH S CODE Chapter Four ’ JU DG E LY NCH S JURORS Chapter Five THE JURISDICTION OF JUDG E LYN CH Chapter Six ’ SOME OF JUDG E LYNCH S CASES ’ ’ e — Leo (A) Judge Lynch s Cause Cel bre Fr ank — Or ( B ) The Mob Was Or der ly New leans Mafia w . ( C ) The Bur ning of Henry Lo ry CO N TE N T S (D) The Law Never Had a Chance Claude Neal ( E ) Th e Five Thousandth— Raymond G unn ( F ) Twice Lynche d in Texas— Ge or ge Hughes (G) Thr ee Governors Go Into Action 1 9 3 3 Who D efie d (H) Those the Bo sses ( 1 ) I 9 3 7 Chapter Seven THE REVERSALS OF JUDG E LYNCH L nch -Executions in U ni d S s 1 882— 1 y the te tate , 93 7 Bibliography P r efa ce TO HELL WITH THE LAW LYN CHING has many legal definitions : It means one thing in Kentucky and North Carolina and another in Virginia or Minnesota . -

Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2011 Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010 Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Cultural History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Buzard-Boyett, Patricia Michelle, "Race and Justice in Mississippi's Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010" (2011). Dissertations. 740. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/740 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: Dr. William K. Scarborough Director Dr. Bradley G. Bond Dr. Curtis Austin Dr. Andrew Wiest Dr. Louis Kyriakoudes Dr. Susan A. Siltanen Dean of the Graduate School May 2011 The University of Southern Mississippi RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 ABSTRACT RACE AND JUSTICE IN MISSISSIPPI’S CENTRAL PINEY WOODS, 1940-2010 by Patricia Michelle Buzard-Boyett May 2011 “Race and Justice in Mississippi’s Central Piney Woods, 1940-2010,” examines the black freedom struggle in Jones and Forrest counties. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1976

1976 Annual Report National Endowment National Council ior the Arts on the Arts National Endowment National Council 1976 on the Arts Annual Report tor the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. 20506 Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1976, and the Transition Quarter ended September 30, 1976. Respectfully, Nancy Hanks Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1976 Contents Chairman’s Statement 4 Organization 6 National Council on the Arts 7 Architecture ÷ Environmental Arts 8 Dance 20 Education 30 Expansion Arts 36 Federal-State Partnership 50 Literature 58 Museums 66 Music 82 Public Media 100 Special Projects 108 Theatre 118 Visual Arts 126 The Treasury Fund 140 Contributors to the Treasury Fund, Fiscal Year 1976 141 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 148 Financial Summary, Fiscal Year 1976 150 Staff of the National Endowment for the Arts 151 Chairman’s Statement In recognition of the great value to the public of the cans felt the arts to be essential to the quality of life for country’s arts, artists, and cultural institutions, the National participation, many cultural institutions face mounting themselves and their children. Similar attitudes have been gaps between costs and earnings which must be filled by Endowment for the Arts was established in 1965 to help expressed in resolutions of the National Association of to strengthen the arts professionally and to ensure that additional contributions.