Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage 1 & 2 Archaeological Assessment

Stage 1-2 Archaeological Assessment Lora Bay Heights Development (Plan 16R-11037) Lots 47 & 48 SW of King St., Lots 47-49, NE of Arthur St. Part of Minto Street, Within the Townplot of Thornbury. Lot 10, Con 34 Geographic Township of Collingwood Town of The Blue Mountains Grey County, Ontario) Submitted to Travis & Associates and The Ontario Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport Prepared by @ the Museum of Ontario Archaeology 1600 Attawandaron Road, London, ON N6G 3M6 Phone: (519) 641-7222 Fax: (519) 641-7220 Archaeological License: Matthew Beaudoin, Ph.D. P324 Our File: 2019-096 PIF Number: (Stage 1) P324-0414-2019, (Stage 2) P324-0417-2019 July 2019 Original Report submitted to the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport 23 July 2019 Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants Inc., Stage 1-2 Archaeological Assessment, Lora Heights Development, Thornbury, ON ii ______________________________________________________________________________________ Executive Summary A Stage 1 and 2 archaeological assessment was conducted for a proposed residential development of a property roughly 12,816.2 m2 (3.17 ac) in size located within part of Lots 47 & 48 Southwest of King Street, Lots 47-49, Northeast of Arthur Street, Part of Minto Street Within the Townplot of Thornbury, Geographic Township of Collingwood, Town of The Blue Mountains, Grey County, Ontario. Planning for the development of new residential development on the subject property is underway and consultation with the County of Grey established that an archaeological assessment would be required. Timmins Martelle Heritage Consultants Inc. (TMHC) was contracted to undertake the assessment, conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Planning Act and Provincial Policy Statement. -

Time Line by Clare Mclean-Wilson

Time Line By Clare McLean-Wilson 1615 Champlain and the Recollet Missionary Father LeCaron are the first white men to visit the native people that live in what will become Grey County. 1815 Captain Owen, in his ‘little survey schooner’ discovers the harbour that will later be named Owen Sound. 1818 The first native treaty is struck. For the ‘yearly payment for ever of twelve hundred pounds of currency in goods at Montreal Prices’ the land covered by Osprey, Collingwood, Artemesia, Euphrasia and St. Vincent, approximately one million five hundred and ninety two acres, is relinquished by its native occupants. 1833 Charles Rankin comes to survey and lay out townships in “the Wild Land beyond the Simcoe district”. 1835 Tarvas Indians from Wikwemikog and Pottawattamies from the State of Wisconsin join the Ojibway people of this area after their land is given to the Government of the United States. 1836 The Sauking Treaty takes “in the land in the County of Grey from the west of the Townships of Euphrasia and St. Vincent to a line directly west of Owen Sound and extending south from that line probably over all the remainder of the county.” Except Sarawak and Keppel, all of the future Grey County is in white hands. 1841 July 6, the first post office in Grey County is opened in St. Vincent Township. 1848 First year that what will be Grey County has an election for a member of the Provincial Legislative Assembly. 1849 First horse brought to Grey County. It was white and belonged to Arthur Hill Rigland Mulholland, a clergyman. -

The Anishinaabeg of Chief's Point

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-18-2019 1:00 PM The Anishinaabeg of Chief's Point Bimadoshka Pucan The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Darnell, Regna The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Bimadoshka Pucan 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pucan, Bimadoshka, "The Anishinaabeg of Chief's Point" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6161. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6161 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Abstract Deep below the passing footsteps of the public, sacred Medicine Songs and Stories are held within Vault 54 of Museum London in London, Ontario. The oldest known audio recordings of the Anishinaabeg in Ontario were discovered in the summer of 2011 by Bimadoshka Pucan. Contained on wax cylinders and lacquered aluminium discs, songs and stories are recorded by Robert and Elizabeth Thompson of Chief’s Point Indian Reserve #28. Not all recordings are considered sacred by the Anishinaabeg, instead the collection provides a broad range of topics including humour, the fur trade, plant medicine, and family history. Sometime before 1939, at the University of Western Ontario, Dr. Edwin Seaborn organized the production of 19 audio recordings. The March of Medicine in Western Ontario (1944) signaled to their creation by preserving the Saugeen Anishinaabeg oral tradition of the death of Tecumseh, a story that continues to live on within specific families at Saugeen First Nation #29. -

Provincial Plaques Across Ontario

An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Last updated: May 25, 2021 An inventory of provincial plaques across Ontario Title Plaque text Location County/District/ Latitude Longitude Municipality "Canada First" Movement, Canada First was the name and slogan of a patriotic movement that At the entrance to the Greater Toronto Area, City of 43.6493473 -79.3802768 The originated in Ottawa in 1868. By 1874, the group was based in Toronto and National Club, 303 Bay Toronto (District), City of had founded the National Club as its headquarters. Street, Toronto Toronto "Cariboo" Cameron 1820- Born in this township, John Angus "Cariboo" Cameron married Margaret On the grounds of his former Eastern Ontario, United 45.05601541 -74.56770762 1888 Sophia Groves in 1860. Accompanied by his wife and daughter, he went to home, Fairfield, which now Counties of Stormont, British Columbia in 1862 to prospect in the Cariboo gold fields. That year at houses Legionaries of Christ, Dundas and Glengarry, Williams Creek he struck a rich gold deposit. While there his wife died of County Road 2 and County Township of South Glengarry typhoid fever and, in order to fulfil her dying wish to be buried at home, he Road 27, west of transported her body in an alcohol-filled coffin some 8,600 miles by sea via Summerstown the Isthmus of Panama to Cornwall. She is buried in the nearby Salem Church cemetery. Cameron built this house, "Fairfield", in 1865, and in 1886 returned to the B.C. gold fields. He is buried near Barkerville, B.C. "Colored Corps" 1812-1815, Anxious to preserve their freedom and prove their loyalty to Britain, people of On Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls and Region, 43.160132 -79.053059 The African descent living in Niagara offered to raise their own militia unit in 1812. -

Department of History

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY DiSunity and Dispossession: Nawash Ojibwa and Potawatomi in the Saugeen Territory, 1836-1865 by Stephanie McMden A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQWIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JLME, 1997 @ Stephanie McMullen 1997 National Library Biblbthéque nationale 191 ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington OttawaON KiA ON4 ûttawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothéque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or selI reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis ui microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de mïcrofiche/iilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownershp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@t in thts thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts f?om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT This study explores the dual themes of factionalisrn and dispossession arnong the Ojibwa and Potawatomi in the Saugeen Tenitory between 1836 and 1865. Chapter 1 lays the foundation of the study by briefïy examining the evolution of Native-non-Native relations in southem Ontario to 1836- Chapter II focuses on the development of Ojibwa- Potawatomi factionalism in the Saugeen Territory, between 1836 and 1850. -

Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation Et Al. V. the Attorney General of Canada Et Al., 2021 ONSC 4181 COURT FILE NOS.: 94-CQ-050872CM and 03-CV-261134CM1 DATE: 20210729

CITATION: Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation et al. v. The Attorney General of Canada et al., 2021 ONSC 4181 COURT FILE NOS.: 94-CQ-050872CM and 03-CV-261134CM1 DATE: 20210729 ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN: ) ) THE CHIPPEWAS OF SAUGEEN FIRST ) H. W. Roger Townshend, Renée Pelletier, NATION and THE CHIPPEWAS OF ) Cathy Guirguis, Jaclyn C. McNamara, NAWASH UNCEDED FIRST NATION ) Benjamin Brookwell, Krista Nerland, Scott ) Franks, Christopher Evans and Joel Plaintiffs ) Morales, for the Plaintiffs ) – and – ) Michael Beggs, Michael McCulloch, Barry ) Ennis, Carole Lindsay, Alexandra Colizza THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ) and Gary Penner, for the Defendant The CANADA, HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN ) Attorney General of Canada IN RIGHT OF ONTARIO, THE ) CORPORATION OF THE COUNTY OF ) David J. Feliciant, Peter Lemmond, Richard GREY, THE CORPORATION OF THE ) Ogden, Julia McRandall and Jennifer Lepan, COUNTY OF BRUCE, THE ) for the Defendant Her Majesty The Queen in CORPORATION OF THE ) Right of Ontario MUNICIPALITY OF NORTHERN ) BRUCE PENINSULA, THE ) Tammy Grove-McClement, for the CORPORATION OF THE TOWN OF ) Defendant The Corporation of The County SOUTH BRUCE PENINSULA, THE ) of Bruce CORPORATION OF THE TOWN OF ) Jill Dougherty and Debra McKenna, for the SAUGEEN SHORES and THE ) Defendant The Corporation of The CORPORATION OF THE TOWNSHIP OF ) Township of Georgian Bluffs GEORGIAN BLUFFS. ) ) Defendants ) Gregory F. Stewart, for the Defendants The Corporation of The County of Northern ) ) Bruce, The Corporation of the Town of CHIPPEWAS OF NAWASH UNCEDED ) South Bruce Peninsula and The Corporation FIRST NATION and SAUGEEN FIRST ) of the Town of Saugeen Shores NATION ) ) ) Plaintiffs ) – and – ) 2 THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ) HEARD: April 25, 29-30, May 1, 13-16, 22- CANADA and HER MAJESTY THE ) 24, 27-31, June 3-4, 10-11, 21, 28, July 8-10, QUEEN IN RIGHT OF ONTARIO ) 12, 15-16, 19, 22-26, Aug. -

Historic Walking Tour Brochure

Owen Sound, originally known as Sydenham, was first surveyed 1 CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY STATION 9 MACLEAN ESTATE BED & BREAKFAST 16 RIXON HOUSE in 1840. The community gained its current name in 1851, was 1198 1st Ave East D 404 9th St East 894 5th Ave East incorporated as a Town in 1857 and as a City in 1920. Much of Rail service to Owen Sound began Dr. John A. Hershey built this house Built in the late 1850s, this Georgian style home was used for Owen Sound’s history is briefly explained by following these in 1873 and included grain elevators, in 1899 for his family and his medical church services until 1874 (traces of the entry door can still be self-guided tours, with suggested routes highlighted on the freight sheds and a roundhouse, practice, and patients would enter seen on the north façade), then as a private school, a grammar map. the foundations of which can still through the 4th Ave East door. Dr. school and a boarding house. Sold to the Rixons in 1888, it be seen at 13th Street. This modern Hershey would also teach medical stayed in the family until 1973. Many of these sites are designated under the Ontario station was built in 1946, part of students at his practice, including the Heritage Act, marked on the tours with a D . Sites marked a pilot program to modernize famous Dr. Norman Bethune. When Dr. 17 BUTCHART ESTATE with B are part of the Freedom Trail, a trail dedicated CPR facilities after World War II. -

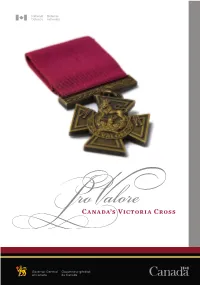

Canada's Victoria Cross

Canada’s Victoria Cross Governor General Gouverneur général of Canada du Canada Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 1 For more information, contact: The Chancellery of Honours Office of the Secretary to the Governor General Rideau Hall 1 Sussex Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0A1 www.gg.ca 1-800-465-6890 Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca 1-877-741-8332 Art Direction ADM(PA) DPAPS CS08-0032 Introduction At first glance, the Victoria Cross does not appear to be an impressive decoration. Uniformly dark brown in colour, matte in finish, with a plain crimson ribbon, it pales in comparison to more colourful honours or awards in the British or Canadian Honours Systems. Yet, to reach such a conclusion would be unfortunate. Part of the esteem—even reverence—with which the Victoria Cross is held is due to its simplicity and the idea that a supreme, often fatal, act of gallantry does not require a complicated or flamboyant insignia. A simple, strong and understated design pays greater tribute. More than 1 300 Victoria Crosses have been awarded to the sailors, soldiers and airmen of British Imperial and, later, Commonwealth nations, contributing significantly to the military heritage of these countries. In truth, the impact of the award has an even greater reach given that some of the recipients were sons of other nations who enlisted with a country in the British Empire or Commonwealth and performed an act of conspicuous Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 5 bravery. -

Owen Sound Sun Times

First Nations' land claim over North Sauble in mediation Owen Sound Sun Times July 3, 2014 By Nelson Phillips, Wiarton Echo Hundreds attend citizens' meeting about first nation claim to stretch of Sauble There's no deal to extend Saugeen First Nation control over more of Sauble Beach north of Main St. and the public would be consulted before such a move, South Bruce Peninsula officials say. The town is now involved in mediation involving a claim to more of the beach by the First Nation, according to a news release issued by the municipality on Wednesday. Meanwhile, the citizens group Friends of Sauble Beach and others plan a public meeting Saturday morning to discuss the issue. The town and First Nation are not involved. "This matter is still proceeding to litigation; and in an attempt to avoid significant costs to taxpayers for the town to engage in what may be a lengthy litigation process, the town is participating in a mediation process to protect the public's interest in Sauble Beach," the town news release says. "We aren't able to tell anything about it," said South Bruce Peninsula administrator Jacquie Farrow-Lawrence. "We're not permitted to talk about it, because it's still in litigation . We do know that the First Nations did not receive all of the land as part of the treaty. "Prior to any decisions being made, a public meeting process will be held that is sanctioned by the town and information will be provided at that time." A flyer advertising the Friends of Sauble Beach meeting, to run from 9:30 to 10:30 a.m. -

Researching the Petun by Charles Garrad

Garrad Researching the Petun 3 Researching the Petun Charles Garrad More than a century of research has led to the present state of knowledge of the Petun occupation of the Petun Country, in the former Collingwood, Nottawasaga, and Mulmur townships. Many individuals, with different skills and interests, have contributed to the study of the Petun between ca. AD 1580 and 1650. This paper outlines the history of investigation of the Petun, describing the work of the more notable contributors. Introduction identification, and interpretation of at least the principal archaeological sites there. This was done The area of Ontario between the Nottawasaga withs a little damage to the resource as possible River and the Blue Mountains, south of andn i co-operation with Petun descendants. Nottawasaga Bay, part of Georgian Bay of Lake The f story o how we arrived at our current Huron, has been occupied intermittently since understanding of Petun history involves the Ice Age. It was occupied historically by the documenting the contributions of many several Iroquoian tribes that were collectively individuals. It is presented here mostly in nicknamed “Petun” by the French.1 The Petun chronological order, while acknowledging thematic were present for only about 70 years (ca. AD trends. Owing to the long-lasting nature of the 1580–1650) but left abundant evidence of their workf o certain researchers, the story at times presence, their role in the fur trade and of the jumps ahead or returns to the work of earlier destructive diseases of the period. Because of the researchers. This history also indicates in the absence of large-scale archaeology, not one Petun footnotes the current locations of many of the house, let alone a village, has been completely notes and collections discussed. -

Section 2 AUTHOR INDEX Abler, Thomas

- 43 - Section 2 AUTHOR INDEX A Abler, Thomas S. Longhouse and palisade: northeastern Iroquoian villages of the seventeenth century, LXII, 17. Acheson, T.W. John Baldwin: portrait of a colonial entrepreneur, LXI, 153. Ac land , James The Canadian inventory of historic buildings, LXIII, 147. Ahearn, Mrs. M.H. The Settlers of March Township, III, 97. Aikens, Charles Journal of a journey from Sandwich to York in the summer of 1806, VI, 15. Aitchison, J.H. The Courts of requests in Upper Canada, XLI, 125. Allan, D. Some of Guelph's old landmarks, XXX, 75. Allin, Cephas D. The British North American League, 1849, XIII, 74. Allinson, C.L.C. John Galt, a character essay, XXX, 43. Angus, Margaret History of preservation activities in Kingston, LXIII, 151. Preservation why and how! LXIII, 139. Armstrong, Christopher A Typical example of immigration into Upper Canada in 1819, XXV,S. Armstrong, Frederick H. The Anglo-American magazine looks at urban Upper Canada on the eve of the railway era, (joint author with Neil C. Hultin), PR, 43. The Carfrae family, a study in early Toronto Toryism, LIV, 161. The First great fire of Toronto, 1849, LIII, 201. Fred Landon, 1880-1969, LXII, 1. George Jervis Goodhue: pioneer merchant of London, Upper Canada, LXIII, 217. The Macdonald-Gowan letters, 1847, LXIII, 1. The Rebuilding of Toronto after the great fire of 1849, LIII, 233. Reformer as capitalist: William Lyon Mackenzie and the printer's strike of 1836, LIX, 187. The Rev. Newton Bosworth: pioneer settler on Yonge Street, LVIII, 163. The Toronto directories and the Negro community in the late 1840's, LXI, Ill. -

Terri Jackson, "The Price Is..."

“The Price is…” Terri Jackson For as long as I have researched Grey County’s Black history, there has always been a looming question, “Who was Colonel Price?” In speaking with other like-minded researchers, the same question has gone unanswered for quite some time. Each spring Naomi Norquay organizes the Grey County Black History Field Trip for Educators from her home near Priceville, Ontario. Her property was owned for a very long time by Rev. Edward Patterson, a Black settler. This tiny community is east of Durham, Ontario, and was known as a hub of freedom seekers and their families coming from the United States via the Underground Railway in the early 1840s, and perhaps as early as the late 1820s. Last May, following a presentation before the tour at the South Grey Museum in Flesherton, a gentleman, having just moved to Priceville two years prior, presented this question: “Who was Priceville named for?” I decided it was time to become involved in the life of this man Price and add some meat to the bones of the story of this man about whom many stories have come to us unverified. I picked the memory banks of resident and historian Les MacKinnon and author Peter Meyler, who in collaboration wrote a revised edition of Broken Shackles,1 to see if either researcher had any notes on Colonel Price. Neither was able to offer more than what the township histories gave.2 Naomi Norquay had acquired dribs and drabs of information through personal interviews with descendants of those early settlers living on the Old Durham Road, near Priceville, but nothing profound was unearthed.