Diversity of Microbial Habitats at Marine Methane Seeps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

Zoo in HRO Sonderausgabe 25 Jahre Rostocker Zooverein 1990-2015

Zoo in HRO Sonderausgabe 25 Jahre Rostocker Zooverein 1990-2015 1990 2015 Gründung GDZ- Rostocker Tagung in Zooverein Rostock 1 4. Tagung Europäischer Zooförderer 1997 in Rostock Editorial Der Rostocker Zoo zählt zu den wichtigsten kommunalen Einrichtungen unserer Hanse- Inhalt stadt. Der Zuspruch der Besucherinnen und Seiten 4 - 5 Besucher und vor allem der Rostockerinnen Kontinuität und Wandel und Rostocker ist wichtig für die zoologische - Wie alles 1963 begann Einrichtung. Darum ist es besonders bemer- Seite 6 kens- und lobenswert, wenn sich Freunde 1990: Gründung des Rostocker des Zoos in einem Förderverein zusammen- Zoovereins geschlossen haben, um einen Großteil ihrer Freizeit im Zoo zu verbringen Seite 10 und ihn mit Spenden und durch Lobbyarbeit zu unterstützen. Es freut mich, 1998: 4. Tagung Europäische dass es dem Zooverein gelungen ist, in seinem Jubiläumsjahr zur „16. Tagung Zooförderer in Rostock Deutscher Zooförderer“ nach Rostock einzuladen. Als Oberbürgermeister Seite 11 werde ich gern Schirmherr der Tagung sein. Ich wünsche allen Vereinsfreun- 2000: Erste Zoo-Tour den weiterhin viel Freude im Rostocker Zoo und viel Schaffenskraft für die Seite 13 nächsten 25 Jahre! Roland Methling 2003: „Schaffen für die Affen“ Oberbürgermeister Seite 14 2005 - 2006: Exkursionen Der Zoo braucht eine Menge Unterstützung, da ist der Seite 15 Zooverein einer unserer stärksten Partner. Seit nunmehr 25 2007: Der Zooverein wächst Jahren steht er zuverlässig an unserer Seite. Mit Spenden Seite 17 und großem Engagement haben die Mitglieder schon einige 2010: 111 Jahre Rostocker Zoo „Spuren“ hinterlassen. So wirkte der Verein mit beim Bau Seite 19 des Wapiti-Geheges, des Großkatzen-Hauses, der Pelikan- 2012: Beginn der Besucherbe- Anlage und der Anlage der Antilopenziesel im Darwineum. -

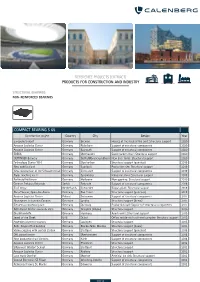

Reference List Construction and Industry

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

EPIDEMIOLOGY of SELECTED INFECTIOUS DISEASES in ZOO-UNGULATES: SINGLE SPECIES VERSUS MIXED SPECIES EXHIBITS Carolina Probst

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SELECTED INFECTIOUS DISEASES IN ZOO-UNGULATES: SINGLE SPECIES VERSUS MIXED SPECIES EXHIBITS Carolina Probst, DVM,* Heribert Hofer, MSc, PhD, Stephanie Speck, DVM, PhD, and Kai Frölich, DVM, PhD1 Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Alfred-Kowalke Strasse 17, 10315 Berlin, Germany Reprinted with permission. American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, 2005. Joint Annual Conference. Abstract The study analyses the epidemiology of selected infectious diseases of 65 different species within the four families of bovids, cervids, camelids and equids in one czech and nine German zoos. It is based on a survey of all epidemiologic data since 1998. Furthermore 900 blood samples taken between 1998 and 2005 are screened for the presence of antibodies against selected viral and bacterial pathogens. The results are linked to the epidemiologic data. Introduction The concept of mixed species exhibits increasingly becomes important in European zoos. It is an important form of behavioral enrichment, it optimizes the use of space and it is of great educational value for visitors, giving them an impression of ecological connections. But until now it has not been elucidated whether the kind of exhibit may lead to an increase in the prevalence of specific infections. The aims of this study are to evaluate the exposure of zoo-ungulates to a variety of disease pathogens that can be transmitted between different species and to assess the epidemiology of mixed exhibits. We are interested in the following questions: 1. Which selected infectious agents are zoo ungulates exposed to? 2. What is the seroprevalence against these agents? 3. Is there a correlation between seroprevalence and the following factors: - animal exhibition system (single species / mixed species exhibit) - population density and animal movements - interspecific contact rates 4. -

Canid, Hye A, Aardwolf Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (Camp) Canid, Hyena, & Aardwolf

CANID, HYE A, AARDWOLF CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (CAMP) CANID, HYENA, & AARDWOLF CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN (CAMP) Final Draft Report Edited by Jack Grisham, Alan West, Onnie Byers and Ulysses Seal ~ Canid Specialist Group EARlliPROMSE FOSSIL RIM A fi>MlY Of CCNSERVA11QN FUNDS A Joint Endeavor of AAZPA IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Hyaena Specialist Group IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Specialist Group CBSG SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION The work of the Captive Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by gellerous colltributiolls from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council: Conservators ($10,000 and above) Federation of Zoological Gardens of Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Claws 'n Paws Australasian Species Management Program Great Britain and Ireland BanhamZoo Darmstadt Zoo Chicago Zoological Society Fort Wayne Zoological Society Copenhagen Zoo Dreher Park Zoo Columbus Zoological Gardens Gladys Porter Zoo Cotswold Wildlife Park Fota Wildlife Park Denver Zoological Gardens Indianapolis Zoological Society Dutch Federation of Zoological Gardens Great Plains Zoo Fossil Rim Wildlife Center Japanese Association of Zoological Parks Erie Zoological Park Hancock House Publisher Friends of Zoo Atlanta and Aquariums Fota Wildlife Park Kew Royal Botanic Gardens Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust Givskud Zoo Miller Park Zoo International Union of Directors of Lincoln Park Zoo Granby Zoological Society Nagoya Aquarium Zoological Gardens The Living Desert Knoxville Zoo National Audubon Society-Research Metropolitan Toronto Zoo Marwell Zoological Park National Geographic Magazine Ranch Sanctuary Minnesota Zoological Garden Milwaukee County Zoo National Zoological Gardens National Aviary in Pittsburgh New York Zoological Society NOAHS Center of South Africa Parco Faunistico "La To:rbiera" Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo North of Chester Zoological Society Odense Zoo Potter Park Zoo Saint Louis Zoo Oklahoma City Zoo Orana Park Wildlife Trust Racine Zoological Society Sea World, Inc. -

Ozeaneum Stralsund

Seestr. Knieperwall Alter Markt teich 1/6 2021–2023 closed Heilgeiststr. OZEANEUM Neuer Knieper- Markt Frankendamm Frankenwall Stralsund 1/6 Tribseer Damm teich Karl-Marx-Str. Central Station Franken- P + R Visit our other locations Strelasund Visitor address • MEERESMUSEUM OZEANEUM Stralsund in Stralsund‘s historic city centre Hafenstraße 11 Stralsund meeresmuseum.de 18439 Stralsund, Germany Old Town Island • NAUTINEUM Dänholm Tel.: +49 3831 2650-610 between Stralsund and Rügen Fax: +49 3831 2650-609 Ticket offi ce nautineum.de E-Mail: [email protected] closes one hour • NATUREUM NAUTINEUM before museum at the Darßer Ort lighthouse Opening Hours closing time. natureum-darss.de October – May daily 9:30 am – 6:00 pm June – September daily 9:30 am – 8:00 pm Family discount: Baltic German Oceanographic NATUREUM Sea 24 December closed * 1,00 € discount Museum Foundation 31 December 9:30 am – 3:00 pm per child Darß Katharinenberg 14 – 20 Rügen accompanied by 18439 Stralsund, Germany Stralsund Admission an adult family Tel.: +49 3831 2650-210 Adults 17.00 € member. Family Fax: +49 3831 2650-209 B 105 B 96 Reduced entrance fee 12.00 € discount * E-Mail: [email protected] Children (4 – 16 years) 8.00 € All prices include A 20 Children (0 – 3 years) free VAT, subject to change without At fi rst glance, We thank our sponsors and partners: Combination tickets with notice. our oceans appear silent. MEERESMUSEUM are available Ocean noise pollution (Entry to MEERESMUSEUM can only be Order your due to human activities is guaranteed until 31.12.2020) tickets here: constantly increasing and The German Oceanographic Museum Foundation is funded by: becoming a problem for Information on guided museum tours in many marine animals. -

Vereinsinformation Veranstaltungskalender Wilhelma-Treff Tagesfahrt Neues Aus Der Geschäftsstelle 2021 Liebe Mitglieder Des Fördervereins

Vereinsinformation Veranstaltungskalender Wilhelma-Treff Tagesfahrt Neues aus der Geschäftsstelle 2021 Liebe Mitglieder des Fördervereins, das denkwürdige Jahr 2020 hat unseren Blick geschärft für das, was uns alle verbindet. Ganz nach- drücklich zeigen die Entwicklungen der Pandemie – aber auch deren Folgen für die vernetzte Welt- wirtschaft und die internationalen Beziehungen – wie eng verwoben die globalen Zusammenhänge sind. Deshalb dürfen wir uns gerade in einer Zeit, die uns in so vielerlei Hinsicht einschränkt, nicht aufhalten lassen, unsere Vielfalt rund um die Erde zu schützen und die Zukunft gemeinsam zu gestal- ten: mit Unterstützung für Artenschutzprogramme weltweit, aber auch dem Einsatz für den Erhalt der Biodiversität hier bei uns. So durfte der Betrieb der Wilhelma trotz der achtwöchi- gen Schließung keinen Tag ruhen. Die seltenen Tiere und exotischen Pflanzen galt es zu hegen und zu pflegen. Wenn das Leben weitergeht, ergeben sich auch schöne Ereignis- se. Hinter verschlossenen Toren kam im Frühjahr äußerst seltener und daher sehr wertvoller Nachwuchs bei den Okapis, Bonobos und Poitou-Eseln zur Welt. Später folgten zwei Kälber bei den in der Natur bereits ausgestorbenen Säbelantilopen. Liboso mit Sohn Kenai Solange keine Gäste in den Park durften, machten die Bauarbeiter aus der Not eine Tugend und brachten Wegesanierungen schneller voran, als das mit Publikumsverkehr möglich gewesen wäre. Und als im Mai die Wilhelma wieder öffnen durfte, konnten Mädchen und Jungen staunen, dass der neue Hauptspielplatz mit Regenwald-Motto in aller Stille fertig geworden war. Entsprechend der langen Tradition des Zoologischen-Bota- nischen Gartens ist es wieder gelungen, unseren Freundin- nen und Freunden etwas für die Wilhelma komplett Neues zu bieten. -

(CAMP) Process Reference Manual 1996

Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Process Reference Manual 1996 Edited by Susie Ellis and Ulysses S. Seal IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Process Reference Manual. 1996. Susie Ellis & Ulysses S. Seal (eds.). IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA. The CBSG lnstitutional Conservation Council: These generous contributors make possible the work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Conservators ($10,000 and above) North Carolina Zoological Park Curators ($250-$499) Oklahoma City Zoo EmporiaZoo Australasian Species Management Program Paignton Zool. & Botanical Gardens Orana Park Wildlife Trust California Energy Co., Inc. Parco Natura Viva Garda Zool. Park Marie and Edward D. Plotka Chicago Zoological Society Perth Zoo Racine Zoological Society Columbus Zoological Gardens Phoenix Zoo Roger Williams Zoo Den ver Zoological Gardens Pi tts burgh Zoo The Rainforest Habita! lntemational Union of Directors of Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp Topeka Zoological Park Zoological Gardens Royal Zoological Society of Scotland Metropolitan Toronto Zoo San Antonio Zoo Sponsors ($50-$249) Minnesota Zoological Garden San Francisco Zoo Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo Schonbrunner Tiergarten African Safari Saint Louis Zoo Sedgwick County Zoo Alameda Park Zoo Sea Worid, inc. S unset Zoo ( 1O year commitment) Shigeharu Asakura Walt Disney's Animal Kingdom Taipei Zoo Apenheul Zoo White Oak Conservation Center Territory Wildlife Park Belize Zoo Wildlife Conservation Society- NY The WILDS Brandywine Zoo Zoological Parks Board of Un ion of Gerrnan Zoo Directors Claws 'n Paws Wild Animal Park New South Wales Urban Services Dept. -

KÖLNER Zoos Wirklich Überall – Und So Einfach? Kundin & Kunde Der Sparkasse Kölnbonn

NR. 1/2020 ZEITSCHRIFT DES 63. JAHRGANG KÖLNER ZOOs Wirklich überall – und so einfach? Kundin & Kunde der Sparkasse KölnBonn Ja klar! Bei unserer Direktfiliale entscheiden Sie selbst, wann und wie Sie Ihre Bankgeschäfte erledigen – ob am Telefon oder per Videochat. Persönlich. Digital. Direkt. Wenn’s um Geld geht s Sparkasse sparkasse-koelnbonn.de/direktfiliale KölnBonn Liebe Freunde des Kölner Zoos! In dieser Zeitschrift des Kölner Zoos finden Sie unseren Jahresbericht für das Jahr 2019. Diesem können Sie ent- nehmen, dass es wieder ein sehr erfolgreiches und inten- sives Jahr war. Die erreichten Ergebnisse basieren auf der Arbeit aller Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter. Sie sind eine Teamleistung. Mit dieser beweisen wir auch 2019 wieder, dass wir einer der führenden Zoologischen Gärten Euro- pas sind. Nicht nur als Erholungsraum für die Menschen aus Köln und der Region, nein insbesondere unserem An- spruch als Bildungs- und Naturschutzzentrum konnten wir wieder gerecht werden – das freut uns alle sehr und erfüllt uns mit Stolz. Die Besucherzahlen als auch die vielfältigen Tätigkeiten unserer Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter sowie die Viel- zahl der Projekte und Zuchtprogramme, an denen wir teil- nehmen und unsere Publikumslieblinge sprechen für sich. Ganz besonders erfreut sind wir darüber, dass wir am Biodiversität ist. Der illegale Wildtierhandel, der unkon- 8. April 2019 mit der Renovierung des alten Vogelhauses, trollierte Konsum von Wildtieren, kann immer wieder zu den meisten heute wohl als Südamerikahaus bekannt, be- solchen Katastrophen, wie der Corona-Pandemie führen. ginnen konnten. Die Bausubstanz war letztlich schlechter Dies gilt es zu verhindern. als befürchtet. Umso erleichtert sind wir, dass der Bau läuft – ein späterer Baubeginn hätte vielleicht gar zum Einsturz Eine Zeit wie diese, bedingt durch ein kleines Virus, hat geführt. -

Wilhelma Bei Schmuddelwetter Tour

Wilhelma bei Schmuddelwetter Tour Endlich ein freier Tag, die Kinder stehen bereits drängelnd an der Tür, der Herd ist aus und die Katzen sind versorgt – kurzum: Sie haben sich auf Ihren schon lange ge- planten Wilhelmabesuch gefreut und es kann eigentlich losgehen. Doch ausgerechnet jetzt spielt das Wetter nicht mehr mit, sondern verrückt! Sintflutartiger Regen? Taube- neigroße Hagelkörner? Schneesturm? Kein Grund zur Panik: Die Schmuddelwetter-Tour knüpft die kürzesten Wege zwischen den überdachten Sehenswürdigkeiten der Wilhel- ma – auf dass Sie trotz miesem Klima möglichst trocken und warm von Attraktion zu Attraktion gelangen. Wegpunkt 1 Die Gewächshäuser In den historischen Gewächshäusern können Sie vielfältige Wunderwerke der Pflan- zenwelt entdecken. Nach unterschiedlichen klimatischen Ansprüchen geordnet finden Sie unter anderem Kakteen, Bromelien, Orchideen und zahlreiche andere tropische und subtropische Pflanzen. Viele der tropischen Gewächse blühen unabhängig von der jeweiligen Jahreszeit draußen: So lässt sich selbst mitten im deutschen Winter vom Urlaub im Süden träumen. Je nach Saison erleben Sie hier die Hochblüte der Azaleen, Fuchsien oder Kamelien. Etwa in der Mitte der Gewächshausreihe liegt zudem der schöne Wintergarten mit Palmen, Bananen, saisonal wechselnden Blütenpflanzen und dem Koi-Teich. Von hier aus gelangen Sie auch ins angrenzende Kleinsäuger- und Vogelhaus, in denen Sie Faultieren, Chinchillas und Kurzohrrüsselspringern ebenso begegnen wie zahlreichen bunten und exotischen Vogelarten. © Wilhelma Zoologisch-Botanischer Garten Wilhelma 13 | 70376 Stuttgart | Tel.: 07 11.54 02-0 | Fax: 07 11.54 02-222 | [email protected] | www.wilhelma.de Wegpunkt 2 Das Aquarium Durch den Maurischen Wandelgang erreichen Sie trockenen Fußes das 1967 eingeweih- te Aquarienhaus. Hier können Sie eine kleine Weltreise durch die Unterwassergefilde der Erde unternehmen: von der Nordsee an den Neckar, vom Mittelmeer an den Kongo, vom Mekong ans Barriere-Riff. -

LION (Panthera Leo) BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS DISEASE RISK ASSESSMENT

LION (Panthera leo) BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS DISEASE RISK ASSESSMENT 16 – 20 March 2009 Skukuza, South Africa THE DAVIES FOUNDATION LION (Panthera leo) BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS DISEASE RISK ASSESSMENT 16 - 20 March 2009 WORKSHOP REPORT Convened by: South African National Parks Endangered Wildlife Trust Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Southern Africa Sponsored by: Animal Health for the Environment And Development (AHEAD) Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo John Ball Zoo Society in Grand Rapids Michigan Disney's Animal Kingdom The Davies Foundation Jacksonville Zoo and Garden In collaboration with The Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) of the IUCN Species Survival Commission © Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG SSC / IUCN) and the Endangered Wildlife Trust. The copyright of the report serves to protect the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group workshop process from any unauthorised use. Keet, D.F., Davies-Mostert, H., Bengis, R.G., Funston, P., Buss, P., Hofmeyr, M., Ferreira, S., Lane, E., Miller, P. and Daly, B.G. (editors) 2009. Disease Risk Assessment Workshop Report: African Lion (Panthera leo) Bovine Tuberculosis. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG SSC / IUCN) / CBSG Southern Africa. Endangered Wildlife Trust. The CBSG, SSC and IUCN encourage workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believe that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report reflect the issues discussed and ideas expressed by the participants in the Lion Bovine Tuberculosis Disease Risk Assessment Workshop and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the CBSG, SSC, or IUCN. Acknowledgements: Thanks to Claire Patterson-Abrolat, Linda Downsborough, Kelly Marnewick and Kirsty Brebner of the Endangered Wildlife Trust for providing valuable final editing on the manuscript. -

Population and Habitat Viability Assessment the Stakeholder Workshop

Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment The Stakeholder Workshop 5 – 8 February, 2007 Milwaukee County, Wisconsin Workshop Design and Facilitation: IUCN / SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Workshop Organization: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Endangered Resources WORKSHOP REPORT Photos courtesy of Wisconsin Bureau of Endangered Resources. A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, in collaboration with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources / Bureau of Endangered Resources. Hyde, T., R. Paloski, R. Hay, and P. Miller (eds.) 2007. Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment – The Stakeholder Workshop Report. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN. IUCN encourage meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believe that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report reflect the issues discussed and ideas expressed by the participants in the workshop and do not necessarily reflect the formal policies IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. © Copyright CBSG 2007 Additional copies of Butler’s Gartersnake (Thamnophis butleri) in Wisconsin: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment – The Stakeholder Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist