Foraging Behaviour in Bumblebees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018 Holiday participants Gerald and Janet Turner Brian Austin and Mary Laurie-Pile Mike and Val Grogutt Mel and Ann Leggett Ann Greenizan Rina Picciotto Leaders Artur Wiatr www.biebrza-explorer.pl and Tim Strudwick. Report, lists and photos by Tim Strudwick. In Biebrza National Park we stayed at Dwor Dobarz http://dwordobarz.pl/ In Białowieża we stayed at Gawra Pensjon at www.gawra.Białowieża.com Cover photos: sunset over Lawaki fen; fallen deadwood in Białowieża strict reserve. Below: group photo taken at Dwor Dobarz and Biebrza lower basin from Burzyn. This holiday, as for every Honeyguide holiday, also puts something into conservation in our host country by way of a contribution to the wildlife that we enjoyed. The conservation contribution this year of £40 per person was supplemented by gift aid through the Honeyguide Wildlife Charitable Trust, leading to a donation of £490. The donation went to The Workshop of Living Architecture, a small NGO that runs environmental projects in and near Biebrza Marshes. This includes building new nesting platforms for white storks, often in response to storm damage or roof renovation, or simply to replace old nests. The total for all conservation contributions through Honeyguide since 1991 was £124,860 to August 2018. 2 DAILY DIARY Saturday 12 May – Warsaw to Biebrza Following an early flight from Luton, the group arrived at Warsaw airport and soon found local leader Artur and driver Rafael in the arrival hall. After introductions, including the customary carnations for the ladies, and the briefest of delays to resolve a suitcase mix up, we quickly boarded the waiting bus. -

Native and Invasive Ants Affect Floral Visits of Pollinating Honey Bees in Pumpkin Flowers (Cucurbita Maxima)

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Native and invasive ants afect foral visits of pollinating honey bees in pumpkin fowers (Cucurbita maxima) Anjana Pisharody Unni1,3, Sajad Hussain Mir1,2, T. P. Rajesh1, U. Prashanth Ballullaya1, Thomas Jose1 & Palatty Allesh Sinu1* Global pollinator decline is a major concern. Several factors—climate change, land-use change, the reduction of fowers, pesticide use, and invasive species—have been suggested as the reasons. Despite being a potential reason, the efect of ants on fowers received less attention. The consequences of ants being attracted to nectar sources in plants vary depending upon factors like the nectar source’s position, ants’ identity, and other mutualists interacting with the plants. We studied the interaction between fower-visiting ants and pollinators in Cucurbita maxima and compared the competition exerted by native and invasive ants on its pollinators to examine the hypothesis that the invasive ants exacerbate more interference competition to pollinators than the native ants. We assessed the pollinator’s choice, visitation rate, and time spent/visit on the fowers. Regardless of species and nativity, ants negatively infuenced all the pollinator visitation traits, such as visitation rate and duration spent on fowers. The invasive ants exerted a higher interference competition on the pollinators than the native ants did. Despite performing pollination in fowers with generalist pollination syndrome, ants can threaten plant-pollinator mutualism in specialist plants like monoecious plants. A better understanding of factors infuencing pollination will help in implementing better management practices. Humans brought together what continents isolated. One very conspicuous evidence of this claim rests in the rearranged biota. -

Foe-UK-Bee-Identification-Guide.Pdf

Want to know more about rare bumblebees? Found a bumble bee that’s not on here? Take a picture and get it identified at bumblebeeconservation.org. Bee It will be added to on-going research into UK bee populations. identification guide When your wildflowers bloom you should have lots of us coming to visit. We’re not all the same and it’s good to know your guests’ names. So we’ve put together this bee spotter guide to help you identify us. Mason Bee Early Bumblebee Osmia rufa Bombus pratorum Buff-tailed Bumblebee Common Carder Bumblebee Hairy-footed Flower Bee (female) Tawny Mining Bee (female) Forest Cuckoo Bumblebee Bombus terrestris Bombus pascuorum Anthophora plumipes Andrena fulva Bombus sylvestris Honey Bee (worker) Red Mason Bee Hairy-footed Flower Bee (male) Tawny Mining Bee (male) Great Yellow Bumblebee Apis mellifera Osmia bicornis Anthophora plumipes Andrena fulva Bombus distinguendus Early Mining Bee Garden Bumblebee Honey Bee (queen) Willughby’s Leafcutter Bee Red-shanked Carder-bee Bumblebee Andrena haemorrhoa Bombus hortorum Apis mellifera Megachile willughbiella Bombus ruderarius Illustrations by Chris Shields by Illustrations Blue Mason Bee Communal Mining Bee Ivy Mining Bee Red-tailed Bumblebee Short-haired Bumblebee Osmia caerulescens Andrena carantonica Colletes hederae Bombus lapidarius Bombus Subterraneus Davies Mining Bee Fabricus’ Nomad Bee White-tailed Bumblebee Brown-banded Carder Bumblebee Shrill Carder Bumblebee Colletes daviesanus Nomada fabriciana Bombus lucornum Bombus humilis Bombus sylvarum www.foe.co.uk charity. a registered Trust, of the Earth Friends These bee illustrations are not to scale www.foe.co.uk/bees. -

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN and CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE the MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO the MACMILLAN CO

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO A PET QUEEN OF BOMBUS TERRESTRIS INCUBATING HER BROOD. (See page 139.) THE HUMBLE-BEE ITS LIFE-HISTORY AND HOW TO DOMESTICATE IT WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF ALL THE BRITISH SPECIES OF BOMBUS AND PSITHTRUS BY \ ; Ff W. U SLADEN FELLOW OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON AUTHOR OF 'QUEEN-REARING IN ENGLAND ' ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS AND DRAWINGS BY THE AUTHOR AND FIVE COLOURED PLATES PHOTOGRAPHED DIRECT FROM NA TURE MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1912 COPYRIGHT Printed in ENGLAND. PREFACE The title, scheme, and some of the contents of this book are borrowed from a little treatise printed on a stencil copying apparatus in August 1892. The boyish effort brought me several naturalist friends who encouraged me to pursue further the study of these intelligent and useful insects. ..Of these friends, I feel especially indebted to the late Edward Saunders, F.R.S., author of The Hymen- optera Aculeata of the British Islands, and to the late Mrs. Brightwen, the gentle writer of Wild Nattcre Won by Kindness, and other charming studies of pet animals. The general outline of the life-history of the humble-bee is, of course, well known, but few observers have taken the trouble to investigate the details. Even Hoffer's extensive monograph, Die Htimmeln Steiermarks, published in 1882 and 1883, makes no mention of many remarkable can particulars that I have witnessed, and there be no doubt that further investigations will reveal more. -

Pollination of Cultivated Plants in the Tropics 111 Rrun.-Co Lcfcnow!Cdgmencle

ISSN 1010-1365 0 AGRICULTURAL Pollination of SERVICES cultivated plants BUL IN in the tropics 118 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO 6-lina AGRICULTUTZ4U. ionof SERNES cultivated plans in tetropics Edited by David W. Roubik Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Balboa, Panama Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations F'Ø Rome, 1995 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-11 ISBN 92-5-103659-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. FAO 1995 PlELi. uion are ted PlauAr David W. Roubilli (edita Footli-anal ISgt-iieulture Organization of the Untled Nations Contributors Marco Accorti Makhdzir Mardan Istituto Sperimentale per la Zoologia Agraria Universiti Pertanian Malaysia Cascine del Ricci° Malaysian Bee Research Development Team 50125 Firenze, Italy 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Stephen L. Buchmann John K. S. Mbaya United States Department of Agriculture National Beekeeping Station Carl Hayden Bee Research Center P. -

Wild Bees in the Hoeksche Waard

Wild bees in the Hoeksche Waard Wilson Westdijk C.S.G. Willem van Oranje Text: Wilson Westdijk Applicant: C.S.G. Willem van Oranje Contact person applicant: Bart Lubbers Photos front page Upper: Typical landscape of the Hoeksche Waard - Rotary Hoeksche Waard Down left: Andrena rosae - Gert Huijzers Down right: Bombus muscorum - Gert Huijzers Table of contents Summary 3 Preface 3 Introduction 4 Research question 4 Hypothesis 4 Method 5 Field study 5 Literature study 5 Bee studies in the Hoeksche Waard 9 Habitats in the Hoeksche Waard 11 Origin of the Hoeksche Waard 11 Landscape and bees 12 Bees in the Hoeksche Waard 17 Recorded bee species in the Hoeksche Waard 17 Possible species in the Hoeksche Waard 22 Comparison 99 Compared to Land van Wijk en Wouden 100 Species of priority 101 Species of priority in the Hoeksche Waard 102 Threats 106 Recommendations 108 Conclusion 109 Discussion 109 Literature 111 Sources photos 112 Attachment 1: Logbook 112 2 Summary At this moment 98 bee species have been recorded in the Hoeksche Waard. 14 of these species are on the red list. 39 species, that have not been recorded yet, are likely to occur in the Hoeksche Waard. This results in 137 species, which is 41% of all species that occur in the Netherlands. The species of priority are: Andrena rosae, A. labialis, A. wilkella, Bombus jonellus, B. muscorum and B. veteranus. Potential species of priority are: Andrena pilipes, A. gravida Bombus ruderarius B. rupestris and Nomada bifasciata. Threats to bees are: scaling up in agriculture, eutrophication, reduction of flowers, pesticides and competition with honey bees. -

Beewalk Report 2020

BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 About BeeWalk BeeWalk is a standardised bumblebee-monitoring scheme active across Great Britain since 2008, and this report covers the period 2008–19. The scheme protocol involves volunteer BeeWalkers walking the same fixed route (a transect) at least once a month between March and October (inclusive). This covers the full flight period of the bumblebees, including emergence from overwintering and workers tailing off. Volunteers record the abundance of each bumblebee species seen in a 4 m x 4 m x 2 m ‘recording box’ in order to standardise between habitats and observers. It is run by Dr Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (BBCT). To contact the scheme organisers, please email [email protected]. Acknowledgements We are indebted to the volunteers and organisations past and present who have contributed data to the scheme or have helped recruit or train others in connection with it. Thanks must also go to all the individuals and organisations who allow or even actively promote access to their land for bumblebee recording. We would like to thank the financial contribution by the Redwing Trust, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Garfield Weston Foundation and the many other organisations, charitable trusts and individuals who have supported the BeeWalk scheme in particular, and the Bumblebee Conservation Trust in general. In particular, the Biological Records Centre have provided website support, data storage and desk space free of charge. Finally, we would like to thank the photographers who have allowed their excellent images to be used as part of this BeeWalk Annual Report. -

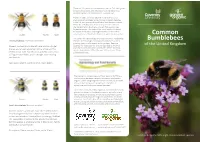

Bumblebee in the UK

There are 24 species of bumblebee in the UK. This field guide contains illustrations and descriptions of the eight most common species. All illustrations 1.5x actual size. There has been a marked decline in the diversity and abundance of wild bees across Europe in recent decades. In the UK, two species of bumblebee have become extinct within the last 80 years, and seven species are listed in the Government’s Biodiversity Action Plan as priorities for conservation. This decline has been largely attributed to habitat destruction and fragmentation, as a result of Queen Worker Male urbanisation and the intensification of agricultural practices. Common The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security is conducting Tree bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) research to encourage and support bumblebees in food Bumblebees growing areas on allotments and in gardens. Bees are of the United Kingdom Queens, workers and males all have a brown-ginger essential for food security, and are regarded as the most thorax, and a black abdomen with a white tail. This important insect pollinators worldwide. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of the world’s food, over 70 are recent arrival from France is now present across most pollinated by bees. of England and Wales, and is thought to be moving northwards. Size: queen 18mm, worker 14mm, male 16mm The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security (CAFS) is a joint initiative between Coventry University and Garden Organic, which brings together social and natural scientists whose collective research expertise in the fields of agriculture and food spans several decades. The Centre conducts critical, rigorous and relevant research which contributes to the development of agricultural and food production practices which are economically sound, socially just and promote long-term protection of natural Queen Worker Male resources. -

WENTLOOGE LEVEL INVERTEBRATE SURVEY, 2019 David Boyce

WENTLOOGE LEVEL INVERTEBRATE SURVEY, 2019 David Boyce DC Boyce Ecologist October 2019 1. INTRODUCTION This report details the findings of an invertebrate survey carried out under contract to Green Ecology. The survey aims to assess the importance for invertebrates of the area of Wentlooge Level shown on Figure 2.1 below. The site is in Wales, on the Gwent Levels; an extensive area of grazing marsh on the north-western side of the Bristol Channel. Wentlooge Level lies in the western part of this area, between the cities of Cardiff to the west and Newport to the east. A central grid reference for the site approximates to ST276817. The grazing marsh ditches of the Gwent Levels support a nationally important assemblage of aquatic plants and invertebrates. It also has one of the last remaining UK populations of the threatened shrill carder bumblebee Bombus sylvarum. For these reasons, much of the area is notified as a series of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The whole of the Wentlooge Level site lies within the Gwent Levels – St. Brides SSSI. Both the shrill carder bumblebee and the brown-banded carder bumblebee Bombus humilis, which also has a strong population on the Gwent Levels, are additionally listed in Section 7 of the Environment (Wales) Act 2016 as Species of Principal Importance for the conservation of biodiversity in Wales. 2. METHODS The first phase of survey work was undertaken in two blocks of two days, the first session being carried out on the 1st and 2nd of May 2019 and the second on the 22nd and 23rd May. -

Ants and Bees Date: May 13-17

Toddler Club Program Lesson Plan Theme 10: Bugs Week 2: Ants and Bees Date: May 13-17 Objective: This week the children will learn about ants and bees. The will learn how to identify these Parents as Partners: Card #38 insects and how to stay safely away from their bites and stings. Spanish Vocabulary: hormiga, hormiguero, abeja, picadura, torax, abdomen, English Vocabulary: ant, anthill, bee, sting, thorax, abdomen, antennae, bug antenas, bicho American Sign Language (ASL): ant, anthill, bee, sting, thorax, abdomen, antennae, bug LESSON Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday COMPONENTS UNITE:" Shoo Fly." Ask children if UNITE: Sing "The Insect Song" head, UNITE: Discuss the places where we UNITE: Act out the song, "Baby UNITE: Review all that we learned they have been bothered by a fly thorax and abdomen song in the can find bugs and mosquitos. Bumblebee." about ants and bees. CALM: Learn and practice the tune of head, shoulders, knees and CALM: Point out the "bzz, bzz, bzz" CALM: Invite the children to copy CALM: Talk about breathing "buzzing breathing." toes. sound that the bees make is called this breathing pattern. exercises and how they relax you. CONNECT: Send well wishes to all CALM: Learn to take deep breath and the buzzing sound. CONNECT: Play a game with your CONNECT: Partner children and Starting the Day the kids that are absent. release it. CONNECT: Demonstrate the Index finger by making circles in the have them try this game, and then BUILD COMMUNITY: Pass around CONNECT: Use Max to welcome anticipation game called, Buzzing air with a buzzing sound and landing switch roles. -

Bumblebee Species Differ in Their Choice of Flower Colour Morphs of Corydalis Cava (Fumariaceae)?

Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)? Myczko, Ł., Banaszak-Cibicka, W., Sparks, T.H Open access article deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Myczko, Ł, Banaszak-Cibicka, W, Sparks, TH & Tryjanowski, P 2015, 'Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)?' Apidologie, vol 46, no. 3, pp. 337-345. DOI 10.1007/s13592-014-0326-x ISSN 0044-8435 ESSN 1297-9678 Publisher: Springer Verlag The final publication is available at Springer via https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13592-014- 0326-x This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited. Copyright 2014© and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. Apidologie (2015) 46:337–345 Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0326-x Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)? Łukasz MYCZKO, Weronika BANASZAK-CIBICKA, Tim H. SPARKS, Piotr TRYJANOWSKI Institute of Zoology, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 71C, 60-625, Poznań, Poland Received 6 June 2014 – Revised 18 September 2014 – Accepted 6 October 2014 Abstract – Bumblebee queens require a continuous supply of flowering food plants from early spring for the successful development of annual colonies. -

The Blight of the Bumblebee: How Federal Conversation Efforts and Pesticide Regulations Inadequately Protect Invertebrate Pollinators from Pesticide Toxicity

Journal of Food Law & Policy Volume 13 Number 2 Article 9 2017 The Blight of the Bumblebee: How Federal Conversation Efforts and Pesticide Regulations Inadequately Protect Invertebrate Pollinators from Pesticide Toxicity Emily Helmick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp Part of the Food and Drug Law Commons Recommended Citation Helmick, E. (2018). The Blight of the Bumblebee: How Federal Conversation Efforts and Pesticide Regulations Inadequately Protect Invertebrate Pollinators from Pesticide Toxicity. Journal of Food Law & Policy, 13(2). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp/vol13/iss2/9 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Food Law & Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Blight of the Bumblebee: How Federal Conservation Efforts and Pesticide Regulations Inadequately Protect Invertebrate Pollinators From Pesticide Toxicity INTRODUCTION Over three-quarters of global crop production depends upon insect pollination; in other words, one in three bites of food relies on bugs to reach your dining room table.1 Bee pollination helps produce crops such as apples, citrus, onions, blueberries, cucumbers, avocadoes, coffee, and pumpkins, to name a few.2 Cross-pollination from wild bees, such as the bumblebee, contribute to ninety percent (90%) of wild plant growth.3 In addition to being essential to food production, bees also significantly contribute to the economy, adding more than $15 billion to the United States’ agricultural industry alone.4 Valuable cash crops reliant on pollination, such as coffee and cocoa, are important sources of income in developing countries, not to mention daily indulgences throughout the world.5 Were bees to vanish completely, that morning cup of coffee or slice of Dedicated to my parents, David and Kelli Helmick, who instilled in me the values of prioritizing an education.