Alexander Hamilton & the Knickerbockers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louisa Wood Ruby

CHAPTER ONE DUTCH ART AND THE HUDSON VALLEY PATROON PAINTERS Louisa Wood Ruby One of the earliest "schools" of American painting, the Hudson Valley patroon painters, has often been considered to have derived from seventeenth-century English portraiture. Portraits of English aristo- crats appealed to Dutch patroons as displays of the kind of social status they aspired to in their new country. British mezzotints after original paintings by Sir Godfrey Kneller and others provided the patroon painters with readily available models on which to base their portraits of wealthy Dutch Americans. Unfortunately, this convincing analysis vastly underestimates the influence of Dutch art and taste on the development of these paintings. Frequently overlooked in the discussion of the appeal of British portraiture to Dutch patroons is the fact that English portraiture of the seventeenth century was, in fact, a direct descendant of the Netherlandish portrait tradition. Kneller, the main source for the mez- zotints that flooded New York, was trained in Amsterdam. Sir Peter Lely was born in Holland, and of course Sir Anthony Van Dyck was from Antwerp. Wealthy Dutch families in New York would have been aware of the Netherlandish tradition through works of art they brought with them from their homeland. Indeed, the first paintings produced in New Amsterdam and early New York were essentially Dutch, since no other tradition existed here at the time. When British mezzotints finally arrived in 17 10, they did indeed appeal to the patroon families, most likely because they were works grounded in the Dutch tradition, then overlaid with elements of British culture and style. -

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index

The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1760-1779 Volume 1 Index References to earlier volumes are indicated by the volume number followed by a colon and page number (for example, 1:753). Achilles: references to, 323 Active (ship): case of, 297 Act of 18 April 1780: impact of, 70, 70n5 Act of 18 March 1780: defense of, by John Adams, 420; failure of, 494–95; impact of, 70, 70n5, 254, 256, 273n10, 293, 298n2, 328, 420; passage of, 59, 60n2, 96, 178, 179n1 Adams, John, 16, 223; attitude toward France, 255; and bills of exchange, 204n1, 273– 74n10, 369, 488n3, 666; and British peace overtures, 133, 778; charges against Gillon, 749; codes and ciphers used by, 7, 9, 11–12; and commercial regulations, 393; and commercial treaties, 645, 778; commissions to, 291n7, 466–67, 467–69, 502, 538, 641, 643, 645; consultation with, 681; correspondence of, 133, 176, 204, 393, 396, 458, 502, 660, 667, 668, 786n11; criticism of, 315, 612, 724; defends act of 18 March 1780, 420; documents sent to, 609, 610n2; and Dutch loans, 198, 291n7, 311, 382, 397, 425, 439, 677, 728n6; and enlargement of peace commission, 545n2; expenses of, 667, 687; French opposition to, 427n6; health of, 545; identified, 801; instructions to, 152, 469–71, 470–71n2, 502, 538, 641, 643, 657; letters from, 115–16, 117–18, 410–11, 640–41, 643–44, 695–96; letters to, 87–89, 141–43, 209–10, 397, 640, 657, 705–6; and marine prisoners, 536; and mediation proposals, 545, 545n2; as minister to England, 11; as minister to United Provinces, 169, 425; mission to Holland, 222, 290, 291n7, 300, 383, 439, -

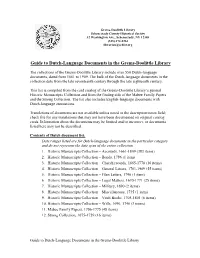

Guide to Dutch-Language Documents in the Grems-Doolittle Library

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave., Schenectady, NY 12305 (518) 374-0263 [email protected] Guide to Dutch-Language Documents in the Grems-Doolittle Library The collections of the Grems-Doolittle Library include over 550 Dutch-language documents, dated from 1661 to 1909. The bulk of the Dutch-language documents in the collection date from the late seventeenth century through the late eighteenth century. This list is compiled from the card catalog of the Grems-Doolittle Library’s general Historic Manuscripts Collection and from the finding aids of the Mabee Family Papers and the Strong Collection. The list also includes English-language documents with Dutch-language annotations. Translations of documents are not available unless noted in the description/notes field; check file for any translations that may not have been documented on original catalog cards. Information about the documents may be limited and/or incorrect, or documents listed here may not be described. Contents of Dutch document list: Date ranges listed are for Dutch-language documents in the particular category and do not represent the date span of the entire collection. 1. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Accounts, 1661-1809 (383 items) 2. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Bonds, 1786 (1 item) 3. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Church records, 1665-1778 (16 items) 4. Historic Manuscripts Collection – General Letters, 1701-1909 (55 items) 5. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Glen Letters, 1796 (1 item) 6. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Legal Matters, 1670-1771 (25 items) 7. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Military, 1690 (2 items) 8. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Miscellaneous, 1735 (1 item) 9. Historic Manuscripts Collection – Vault Books, 1705-1801 (6 items) 10. -

Champlain Hudson CHPE Properties, Inc. Pieter Schuyler Building Albany

State of New York Department of State One Commerce Plaza 99 Washington Avenue Andrew M. Cuomo Cesar A. Perales Governor Albany, NY 12231-0001 Secretary of State June 8, 2011 Mr. Donald Jessome, President/CEO Champlain Hudson Power Express Inc. and CHPE Properties, Inc. Pieter Schuyler Building 600 Broadway Albany, NY 12207-2283 Re: F-2010-1162 U.S. Dept. ofEnergy #: PP-362 U.S. Army Corps ofEngineers Application #: 2009- 01089-EHA NYS Public Service Commission Application #: 10- T-0139 Champlain-Hudson Power Express 1,000 megawatt HVDC electric transmission system from Canada to New York City Conditional Concurrence with Consistency Certification Dear Mr. Jessome: The Department ofState (DOS) has completed its review ofthe consistency certification and data and information for the above referenced project in accordance with the federal Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA). Pursuant to 15 CFR 930.4 and 930.62, DOS conditionally concurs with the consistency certification for the project under the enforceable policies ofthe New York State Coastal Management Program (CMP). This transmission project promises to deliver a tremendous supply ofclean, renewable hydropower from Canada to the New York City Metropolitan Area, one ofthe nation's largest energy markets. Ifconstructed as proposed and conditioned, the project can provide several important energy benefits. The electricity will serve the New York Independent Systems Operator (NYISO) load center in Zone J and adjacent zones, a high need area. Hydro-power, a renewable energy source, diversifies the State's energy portfolio. Because the electricity is predominantly generated by hydropower, it will improve air quality by displacing less clean generators and will not contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. -

The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mohler, Melinda M., "A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4755. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4755 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jack Hammersmith, Ph.D., Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Kenneth Fones-World, Ph.D. Martha Pallante, Ph.D. -

The Lost City of Tryon Trail Is an Approved Historic Trail Of

The Lost City of Tryon Trail is an approved Historic Trail of the Boy Scouts of America and is administered by the Seneca Waterways Council Scouting Historical Society. It offers hikers a fantastic opportunity to experience a geographic location of enduring historic significance in Upstate New York. 2018 EDITION Seneca Waterways Council Scouting Historical Society 2320 Brighton-Henrietta Town Line Road, Rochester, NY 14623 version 2.0 rdc 10/2018 A Nice Hike For Any Season Introduction The Irondequoit Bay area was once at the crossroads of travel and commerce for Native Americans. It was the home of the Algonquin and later the Seneca, visited by a plethora of famous explorers, soldiers, missionaries and pioneers. This guidebook provides only a small glimpse of the wonders of this remote wilderness prior to 1830. The Lost City of Tryon Trail takes you through a historic section of Brighton, New York, in Monroe County’s Ellison Park. The trail highlights some of the remnants of the former City of Tryon (portions of which were located within the present park) as well as other historic sites. It was also the location of the southernmost navigable terminus of Irondequoit Creek via Irondequoit Bay, more commonly known as “The Landing.” The starting and ending points are at the parking lot on North Landing Road, opposite the house at #225. Use of the Trail The Lost City of Tryon Trail is located within Ellison Park and is open for use in accordance with park rules and regulations. Seasonal recreation facilities, water, and comfort stations are available. See the park’s page on the Monroe County, NY website for additional information. -

Correspondence of Maria Van Rensselaer (1669-1689)

CORRESPONDENCE OF MARIA VAN RENSSELAER 1669-1689 Translated and edited by A. J. F. VAN LAER Archivist, Archives and History Division ALBANY THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK I 935 PREFACE In the preface to the Correspondence of Jeremias van Rens selaer, which was piiblished in 1932, attention was called to the fact that after the death of Jeremias van Rensselaer his widow carried on a regular correspondence with her husband's youngest brother, Richard van Rensselaer, in regard to the administration of the colony of Rensselaerswyck, and the plan was announced to publish this correspondence in another volume. This plan has been carried into effect in the present volume, which contains translations of all that has been preserved of the correspondence of Maria van Rensselaer, including besides the correspondence with her brother-in-law many letters which passed between her and her brother Stephanus van Cortlandt and other members of the Van Cortlandt family. Maria van Rensselaer was born at New York on July 20, 1645, and was the third child of Oloff Stevensen van Cortlandt and his wife Anna Loockermans. She married on July 12, 1662, when not quite 17 years of age, Jeremias van Rensselaer, who in 1658 had succeeded his brother Jan Baptist van Rensse laer as director of the colony of Rensselaerswyck. By him she had four sons and two daughters, her youngest son, Jeremias, being born shortly after her husband's death, which occurred on October 12, 1674. As at the time there was no one available who could succeed Jeremias van Rensselaer as director of the colony, the burden of its administration fell temporarily upon his widow, who in this emergency sought the advice of her brother Stephanus van Cortlandt. -

John Trumbull of the Signing of the Declaration of Independence

Bicentennial Moment #2: the Naming of Livingston County, New York Livingston County was named in honor of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston (1746-1813), a man who never resided Livingston County, but who was among the Founding Fathers of the United States of America. Livingston was the eldest son of Judge Robert Livingston (1718–1775) and Margaret (née Beekman) Livingston, uniting two wealthy Hudson River Valley families. Among his many contributions, Livingston was a member of the Second Continental Congress, co-author of the Declaration of Independence, and in 1789 he administered the oath of office to President George Washington. As a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, Livingston worked alongside Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Roger Sherman. A regional and national luminary, Livingston served as Chancellor of the Supreme Court of New York (1777 to 1801). As the United States Minister to France from 1801 to 1804, he was one of the key figures in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon Bonaparte, a sale that marked a turning point in the relationship between the two nations. During his time as U.S. Minister to France, Livingston met Robert Fulton, with whom he developed the first viable steamboat, the North River Steamboat, whose home port was at the Livingston family home of Clermont Manor in Clermont, New York. In addition to the naming of Livingston County in his honor, Robert R. Livingston's legacy lives on in numerous ways including a statue commissioned by the State of New York and placed in the National Statuary Hall at the U.S. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of Power, Privilege and Prestige in the Revolutionary Era

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of power, privilege and prestige in the Revolutionary era Jennifer Megan Janson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Janson, Jennifer Megan, "Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756--1802: Dynamics of power, privilege and prestige in the Revolutionary era" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 797. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/797 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sarah Livingston Jay, 1756-1802: Dynamics of Power, Privilege and Prestige in the Revolutionary Era Jennifer Megan Janson Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Colonial and Revolutionary History Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Department Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Committee Chair Ken Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. -

The Colonial Family: Kinship Nd Power Peter R

The Colonial Family: Kinship nd Power Peter R. Christop New York State Library ruce C. Daniels in a 1985 book review wrote: “Each There is a good deal of evidence in the literature, year since the late 1960sone or two New England town therefore, that in fact the New England town model may studies by professional historians have been published; not at all be the ideal form to use in studying colonial lheir collective impact has exponentially increased our New York social structure. The real basis of society was knowledge of the day-to-day life of early America.“’ not the community at all, but the family. The late Alice One wonders why, if this is so useful an historical P. Kenney made the first step in the right direction with approach, we do not have similar town studies for New her study of the Gansevoort family.6 It is indeed the York. It is not for lack of recordsthat no attempt hasbeen family in colonial New York that historians should be made. Nor can one credit the idea that modern profes- studying, yet few historians have followed Kenney’s sional historians, armed with computers, should feel in lead. A recent exception of note is Clare Brandt’s study any way incapable of dealing with the complexity of a of the Livingston family through several generations.7 multinational, multiracial, multireligious community. However, we should note that Kenney and Brandt have restricted their attention to persons with one particular One very considerable problem for studying the surname, ignoring cousins, grandparents, and colonial period was the mobilily Qf New Yorkers, grandchildren with other family namesbut nonetheless especially the landed and merchant class. -

Columbia County

History of Columbia County Bench and Bar Helen E. Freedman Contents I. County Origins 2 a. General Narrative 2 b. Legal and Social Beginnings 3 c. Timeline 4 II. County Courts and Courthouses 6 III. The Bench and The Bar 10 a. Judges and Justices 10 b. Attorneys and District Attorneys 19 c. Columbia County Bar Association 24 IV. Notable Cases 25 V. County Resources and References 28 a. Bibliography 28 b. County Legal Records and their Location 28 c. County History Contacts 29 i. Town and Village Historians 30 ii. Local Historical Societies 31 iii. County, Town & Village Clerks 32 1 08/13/2019 I. County Origins a. General Narrative In September of 1609, Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company, set foot in what was to become Columbia County. When he stepped off his vessel, the Half Moon, he was the first European to arrive and was greeted by natives from the Mohican tribes who had settled in what is Stockport today.1 Starting in about 1620, Dutch immigrants settled the area along the Hudson River and extending east to the Massachusetts border, pursuant to land patents issued by the Dutch West India Company. Large manorial tracts were granted to the Van Rensselaer family, mostly in the northern part of the county and further north, starting in 1629. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, a dia- mond and pearl merchant from Amsterdam and a director of the Dutch West India Company, founded the Manor of Rensselaerswyck in 1630, which included what is now the Capital District and Rensselaer and part of Columbia Counties.