Sakari Kainulainen & Sami Kivelä

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Pressure Drop Measurements for Estimating Ventilation and Paper Porosity* by C

Beitrage zur Tabakforschung International ·Volume 10 ·No. 1 ·December 1979 The Use of Pressure Drop Measurements for Estimating Ventilation and Paper Porosity* by C. H. Keith Celanese Fibers Company, Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.A. The recent increase in the number and volume of ven 20 °C. For measurements on ventilated filters, the perti tilated cigarette brands has created a need for a simple, nent readings are the normal open cigarette pressure drop, non-destructive means of measuring the degree of air L\p 0 , the cigarette pressure drop with the filter vents dilution. Two techniques currently in use require the use closed, L\ p0, and the filter pressure drop, L\ Pf· For measure of auxiliary equipment or specialized analyses. One of ments on tobacco columns, a fully encapsulated pressure these is the sleeve method of Norman (1) which encloses drop, L\ p6, is also required. the ventilation portion of the cigarette in a small chamber The basis for the calculation of diluting air flow from and measures the flow into this chamber while a puff or pressure drop is the observation (3, 4, 6, 7) that pressure alternatively a constant flow is withdrawn from the ciga drop is essentially equal to the product of an impedance rette. The degree of air dilution is thus estimated from coefficient, a flow rate and a length (Darcy's Law). While the ratio of the volumetric flow rates. A second method is this relationship is nearly exact only for filter tips, it is that described by Reynolds and Wheeler (2), which en usable to a good approximation in tobacco columns where closes the cigarette except for the burning coal in an at a more complicated flow regime exists. -

HHS Public Access Author Manuscript

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author Manuscript Author ManuscriptCancer Author ManuscriptEpidemiol Biomarkers Author Manuscript Prev. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 02. Published in final edited form as: Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 January ; 21(1): 39–44. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0800. Development of a Method to Estimate Mouth-Level Benzo[a]pyrene Intake by Filter Analysis Yan S. Ding, Theodore Chou, Shadeed Abdul-Salaam, Bryan Hearn, and Clifford H. Watson Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia Abstract Background—Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) is one of the most potent carcinogens generated in cigarette smoke. During smoking, cigarette filters trap a significant portion of mainstream smoke benzo[a]pyrene. This trapped portion is proportional to what exits the end of the filter and is drawn into the mouth of smokers. Methods—We developed a new method to estimate mouth-level BaP intake using filter analysis. In this analysis, cigarettes are smoked by a smoking machine using a variety of conditions to yield a range of mainstream smoke deliveries, which approximate a range of human puffing characteristics. Mainstream smoke BaP collected on Cambridge filter pads and the corresponding 1-cm mouth-end cigarette filter butts is extracted, purified by solid-phase extraction, and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with a fluorescence detector. On the basis of the amount of BaP retained in cigarette butts and the amount collected on pads, we can relate them using a linear regression model. Results—Using this model and subsequently analyzing cigarette filters collected from smokers, we are able to estimate their mouth-level intakes, which smokers received when they consumed cigarettes. -

23/F, 8-Commercial Tower, 8 Sun Yip Street, Chai Wan, Hong Kong Tel 25799398 26930136 Fax (+852) 26027153 Email [email protected]

To Whom it may concern ISO Test methods for cigarette tar and nicotine content are outdated and unrepresentative of the actual yield and toxins intake due to smoker compensation - Countries should adopt the Health Canada Intense test method, like RIVM Holland The old and outdated ISO test criteria for cigarette tar and nicotine content used by the HK Government Lab is way out of date. The industry deliberately perforates the filter and paper of the tobacco rods with tiny holes to ‘cheat’ the current ISO machine test methods. What actually happens is the smokers wrap their fingers and of course mouth around the filter to compensate for the additional dilution air being sucked in through the perforations. The ISO smoking test machine is not real world, does not compensate by blocking the holes and hence reveals test results that are far, far lower than the smokers actually inhale. RIVM, the Dutch Ministry of Health, has adopted the Health Canada Intense smoking test criteria which better reveals the actual tar and nicotine in each cigarette rod since they tape over the perforated holes in the same way that the smoker compensates with fingers and mouth, to seal the holes - and then test the actual values. Attached herewith you can see the vast disparities as revealed in the RIVM test data which show the level of toxics which the smokers actually inhale versus the mythical ISO data preferred and provided by the manufacturers. Countries Kong need to switch to the Health Canada Intense method of cigarette testing asap and inform the public accordingly of the actual level of toxins they inhale when they smoke cigarettes. -

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—A Listing (173 Pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. Plan from 1959 to Enlist Professor

38 2000 Tobacco Industry Projects—a Listing (173 pp.) Project “A”: American Tobacco Co. plan from 1959 to enlist Professors Hirsch and Shapiro of NYU’s Institute of Mathematical Science to evaluate “statistical material purporting to show association between smoking and lung cancer.” Hirsch and Shapiro concluded that “such analysis is not feasible because the studies did not employ the methods of mathematical science but represent merely a collection of random data, or counting noses as it were.” Statistical studies of the lung cancer- smoking relation were “utterly meaningless from the mathematical point of view” and that it was “impossible to proceed with a mathematical analysis of the proposition that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer.” AT management concluded that this result was “not surprising” given the “utter paucity of any direct evidence linking smoking with lung canner.”112 Project A: Tobacco Institute plan from 1967 to air three television spots on smoking & health. Continued goal of the Institute to test its ability “to alter public opinion and knowledge of the asserted health hazards of cigarette smoking by using paid print media space.” CEOs in the fall of 1967 had approved the plan, which was supposed to involve “before-and-after opinion surveys on elements of the smoking and health controversy” to measure the impact of TI propaganda on this issue.”113 Spots were apparently refused by the networks in 1970, so plan shifted to Project B. Project A-040: Brown and Williamson effort from 1972 to 114 Project AA: Secret RJR effort from 1982-84 to find out how to improve “the RJR share of market among young adult women.” Appeal would 112 Janet C. -

Types of Cigarette

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.35.12.925 on 1 December 1980. Downloaded from Thorax, 1980, 35, 925-928 Inhaling habits among smokers of different types of cigarette NICHOLAS J WALD, MARIANNE IDLE, JILLIAN BOREHAM, AND ALAN BAILEY From the ICRF Cancer Epidemiology and Clinical Trials Unit, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, and BUPA Medical Centre, London ABSTRACT Inhaling habits were studied in 1316 men who freely smoked their usual brands of cigarette. An index of inhaling was calculated for each person by dividing the estimated in- crease in carboxyhaemoglobin level from a standard number of cigarettes by the carbon mon- oxide yield of the cigarette smoked. Smokers of ventilated filter cigarettes inhaled 82% more than smokers of plain cigarettes (p<O0OOl) and those who smoked unventilated filter cigarettes inhaled 36% more (p>QOOOl). Cigarette consumption was similar among smokers of each type of cigarette. Assuming that the intake of tar and nicotine is proportional to the inhaling index, the intake in either group of filter cigarette smokers would have been less than that in plain cigarette smokers. Among smokers of unventilated cigarettes, however, the intake would not have been much less. Filter cigarettes, especially those with ventilated health screening examination. The men were copyright. filters (which have perforations in the filter asked about their medical history and their usual through which air can enter and reduce the con- and recent smoking habits. All information was centration of the cigarette smoke), deliver less collected after arrival at the Medical Centre, tar and nicotine than plain cigarettes. They are and the men were not forewarned about the sur- considered less harmful to health, particularly as vey of smoking habits. -

Section V V the DEFENDANTS CAUSED the CHARGED

Section V V THE DEFENDANTS CAUSED THE CHARGED MAILINGS AND WIRE TRANSMISSIONS IN FURTHERANCE OF THE SCHEME TO DEFRAUD A. The Charged Defendants Caused the Mailings and Wire Transmissions 1. The Court finds that, consistent with the allegations set forth in the descriptions of the Racketeering Acts below (see Section V.B), the charged Defendants performed or caused the mailings or wire transmissions described in each of those respective Racketeering Acts to be sent, delivered, or received by the requisite means of transmission consistent with 18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 and 1343. 2. Brown & Williamson has stipulated that the requirements of 18 U.S.C. § 1341 or § 1343 have been met for the following Racketeering Acts: 8, 17, 31, 32, 38, 44, 45, 50, 51, 52, 54, 57, 60, 63, 66, 67, 77, 88, 98, 103, 106, 115, 116, 118, 124, 125, 127, 129, 144. 3. BATCo has stipulated that the requirements of 18 U.S.C. § 1341 or § 1343 have been met for the following Racketeering Acts: 11, 30, 50, 51, 53, 54, 57, 60, 63, 103, and 108. 4. In their responses to Requests for Admission, various Defendants have admitted that certain of the Racketeering Acts were transmitted by the requisite means of transmission (mail or wire), including the following Racketeering Acts: 11, 26, 30, 32, 38, 44-46, 50-55, 57, 60, 63, 66-67, 70, 73, 77, 79, 81, 82, 86, 88-90, 94, 96, 98-99, 103-106, 108-110, 114, and 116. 5. For purposes of the mail fraud violations covered by 18 U.S.C. -

Sporting & Collectors' Sale

SPORTING & COLLECTORS’ SALE Wednesday 25th & Thursday 26th February 2015 OKEHAMPTON STREET EXETER Sporting & Collectors’ Sale For Sale by Auction at St. Edmund’s Court Okehampton Street Exeter EX4 1DU Wednesday 25th February 2015 and Thursday 26th February 2015 Commencing at 10.00am each day On View Saturday 21st February 9am - 12 noon Monday 23rd February 9am - 5.15pm Tuesday 24th February 9am - 5.15pm on morning of sale from 9am Catalogue £5.00 (£7.00 by post) W: www.bhandl.co.uk E: [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @BHandL SPORTING & COLLECTORS’ SALE CATEGORIES DAY ONE Lots CARS, etc. 1- 4 CERAMICS AND GLASS 5-8 SILVER & METALWARES 9-16 HUNTING AND EQUESTRIAN 17-44 TAXIDERMY 45-56 SHOOTING & RELATED 57-73 AIR RIFLES & PISTOLS 74-107 SPORTING GUNS 108-113 GUNS – OTHER CALIBRES 114-171 EDGED WEAPONS 172-350 MEDALS & MILITARIA 351-507 EMERGENCY SERVICES 508-590 FISHING 591-621 OTHER SPORTS (RUGBY, FOOTBALL, TENNIS ETC) 622-638 TRANSPORT AND MOTORING 639-717 PRINTS 718-732 WATERCOLOURS 733-746 MARITIME PICTURES 747-750 MARITIME FITTINGS 751 INSTRUMENTS and NAVIGATION 752-754 SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 755-759 MARINE COLLECTABLES 760-762 MODELS 763-764 **** END OF DAY ONE**** DAY TWO STAMPS 765-828 POSTCARDS & CIGARETTE CARDS 829-896 COINS 897-904 TEXTILES 905-924 DOLLS & TEDDY BEARS 925-996 DIECASTS 997-1091 OO/HO GAUGE RAILWAYS 1092-1166 O GAUGE RAILWAYS 1167-1198 LARGER GAUGE RAILWAY 1199-1200 FULL SIZE RAILWAYS 1201-1210 TOYS & COLLECTABLES 1211-1299 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 1300-1313 DAY 1 - Wednesday 25th February 2015 Sale commences at 10am. -

Coins, Books, Models, Toys & Militaria

COINS, BOOKS, MODELS, TOYS & MILITARIA TUESDAY 19 SEPTEMBER 2017 10am Auction Room, Holsworthy Livestock Market New Market Road, Holsworthy, Devon, EX22 7FA Viewing day before the sale between 2pm-6pm and morning of sale from 8.30am Auctioneer Phil Walter - 01409 259256 / 07951 240305 CONDITIONS OF SALE The auctioneer acts only as agent for the seller (unless otherwise specifically declared). Lots sold are likely to have been subject to wear and tear caused by user or the effects of age and may therefore have faults and imperfections. Buyers are given ample opportunity at viewing times to examine lots to be sold and will be assumed to have done so. They must rely solely on their own skill or judgement as to whether lots are fit for any particular purpose. All prospective purchasers must register and obtain a bidding number prior to the sale. Auctioneers Discretion The Auctioneers have sole discretion (a) to refuse any bid (b) to advance the bidding as he may decide (c) to withdraw or divide any lot or combine one lot with another or others, (d) to exclude any person from the auction rooms and (e) to require pre payment in full. Liability of the Auctioneer and Sellers Faults & Imperfections (if any) are not stated in the catalogue and neither the sellers nor the Auctioneers are responsible for any defects whatsoever. No warranty is given or authorised to be given by the seller or Auctioneer with regard to any lot other than the seller’s right to sell. Any expressed or implied conditions or warranties whether relating to description or quality, are hereby excluded. -

Printmgr File

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, as amended (the “FSMA”) if you are resident in the United Kingdom, or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your existing ordinary shares in British American Tobacco p.l.c. (“BAT” or the “Company” and together with its subsidiary undertakings, the “BAT Group”), please send this document, together with the accompanying form of proxy (the “Proxy Form”), Proxy Form – South Africa (“PFSA”) or Voting Instruction Form, as appropriate, (other than documents or forms personalised to you) as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for delivery to the purchaser or transferee. However, these documents should not be forwarded, distributed or transmitted in, into or from any jurisdiction where to do so would violate the laws of that jurisdiction. If you have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holdings of ordinary shares in BAT (the “BAT Shares”) you should retain these documents and contact the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected. This document should be read in conjunction with the prospectus published by BAT in relation to the Proposed Acquisition (as defined below) on or around the date of this document (the “Prospectus”) relating to the new ordinary shares (the “New BAT Shares”) to be issued pursuant to the Proposed Acquisition. -

WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation

WHO Technical Report Series 1001 WHO study group on tobacco product regulation Report on the scientific basis of tobacco product regulation: Sixth report of a WHO study group The World Health Organization was established in 1948 as a specialized agency of the United Nations serving as the directing and coordinating authority for international health matters and public health. One of WHO’s constitutional functions is to provide objective and reliable information and advice in the field of human health, a responsibility that it fulfils in part through its extensive programme of publications. The Organization seeks through its publications to support national health strategies and address the most pressing public health concerns of populations around the world. To respond to the needs of Member States at all levels of development, WHO publishes practical manuals, handbooks and training material for specific categories of health workers; internationally applicable guidelines and standards; reviews and analyses of health policies, programmes and research; and state-of-the-art consensus reports that offer technical advice and recommendations for decision-makers. These books are closely tied to the Organization’s priority activities, encompassing disease prevention and control, the development of equitable health systems based on primary health care, and health promotion for individuals and communities. Progress towards better health for all also demands the global dissemination and exchange of information that draws on the knowledge and experience of all WHO’s Member countries and the collaboration of world leaders in public health and the biomedical sciences. To ensure the widest possible availability of authoritative information and guidance on health matters, WHO secures the broad international distribution of its publications and encourages their translation and adaptation. -

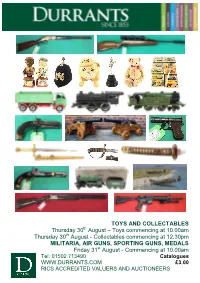

Collectables Commencing at 12.30Pm

TOYS AND COLLECTABLES Thursday 30th August – Toys commencing at 10.00am Thursday 30th August - Collectables commencing at 12.30pm MILITARIA, AIR GUNS, SPORTING GUNS, MEDALS Friday 31st August - Commencing at 10.00am Tel: 01502 713490 Catalogues WWW.DURRANTS.COM £3.00 RICS ACCREDITED VALUERS AND AUCTIONEERS NOTES FOR PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS DURRANTS AUCTIONEERS AND VALUERS Durrants’ experience of Auction Sales dates back to 1853 and since that time we have continued to undertake chattel sales and valuations throughout Norfolk and Suffolk. From our Auction Rooms at Peddars Lane, Beccles we conduct Fine Art and Antique Auction Sales every month, interspersed with Specialist Sales. Our team of Valuers and Auctioneers undertake valuations for probate and insurance purposes and provide advice for sale and family division. RICS accredited Valuers and Auctioneers OUR SERVICE With our own salerooms, experienced staff and removal vehicles we are able to offer a comprehensive and cost effective service to executors, solicitors and private clients. On site inspections at short notice by appointment Experienced valuers throughout the group Verbal advice or comprehensive reports Professional and confidential service Specialist valuations of furniture, ceramics, pictures, silver, jewellery, clocks and watches, books, toys and dolls, stamps, postcards, coins, Militaria, swords, medals Sporting Guns and Antique Firearms Durrants has offices in Beccles, Halesworth, Southwold, Harleston and Diss. Each has a team of experienced Chartered Surveyors and Estate Agents, offering a wide range of services encompassing Agricultural, Residential, Commercial and Investment properties. We also have a specialist Planning and Design Group. FIREARMS We have full R.F.D. capabilities enabling us to sell on your behalf all items that require licences. -

Work-Site Smoking Policy on Employees Who Smoke

Effects of a Restricted Work-Site Smoking Policy on Employees Who Smoke Janet Brigham, PhD, Janet Gross, PhD, Maxine L. Stitzer, PhD, and Linda J. Felch, M4 Introduction example, in the study by Hatsukami et al.,6 smokers who reduced the number of Many institutions throughout the cigarettes smoked by 50% or reduced the United States have moved toward restrict- nicotine yield of their cigarettes by about ing smoking in public places, particularly 50% experienced some craving and with- since the Surgeon General's 1986 report drawal discomfort but reported signifi- on involuntary smoking.1 Several studies cantly less discomfort than total abstain- have indicated that the incidence of ers. On the other hand, West et al.7 found public smoking changes when restricted- that switching to an ultra-low-yield ciga- smoking policies are implemented. Still- rette did not result in any appreciable man et al.2 reviewed empirical evidence of reporting of withdrawal distress, except reduction in smoking at the Johns Hop- for increased hunger. The mechanisms kins medical institutions and concluded thought to cause low-level withdrawal that implementing a smoke-free policy in symptoms under conditions of restricted a large medical center can decrease visible smoking are reduction in blood nicotine smoking and passive exposure to tobacco levels and habit change. smoke. A previous report by Becker et al.3 In a related vein, research on re- indicated that public smoking at the Johns stricted smoking in habitual smokers has Hopkins Children's Center was virtually suggested that smokers may adjust their eliminated in 1987 by implementation of a smoking behavior to offset effects of smoke-free policy.