Northern Review FINAL Yukon College Oct 29.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of the Arctic: the First Year Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council Oulu, Finland, May 16, 2002

UNIVERSITY OF THE ARCTIC University of the Arctic: the First Year Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council Oulu, Finland, May 16, 2002 Introduction The University of the Arctic was officially launched in Rovaniemi, Finland, in conjunction with the first Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council meeting under Finland’s chairmanship and the 10th anniversary of the Rovaniemi process on June 12, 2001. Over 200 people celebrated the Launch of the new University. The guest speakers included Maija Rask, Finland’s Minister of Education, who invited all the Arctic governments to work hard at finding collaborative ways to fund the University of the Arctic and its program, and Professor Asgeir Brekke from the University of Tromsø in Norway , the Chair of the Council of the University of the Arctic since the inception of the idea, who symbolically passed on the Council’s gavel to Sally Adams Webber, President of Yukon College in Canada. The Launch marked the shift from planning of governance structures and programs to the actual implementation of programs. The first year of operation for the University of the Arctic has meant real students, real programs, and a growing enthusiasm and expectation of more to come for those students. The first evaluations of the University of the Arctic’s pilot programs, are being conducted at the time of writing this report. Preliminary results from these evaluations show that, first of all, the early enthusiasts were right in saying that we do need structural solutions to address the need for truly Circumpolar education that takes the needs of the primary client group to heart. -

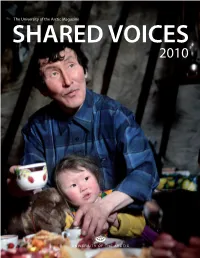

Shared Voices Magazine 2010

The University of the Arctic Magazine SHARED VOICES 2010 UArctic VP Indigenous Building on Classroom Connections: UArctic's Vice-President The Development of 06 Indigenous position is the latest initiative towards building a UArctic Student Association indigenous leadership in UArctic Two former students of governance and program activities. 32 the UArctic write about the Newly appointed VP Indigenous need to create a student association and long-time UArctic supporter, and the advantages that such a Jan Henry Keskitalo, explains the group could provide for the future opportunities on the horizon. development of the organisation. Can Good Governance Save the Arctic? The Arctic is experiencing a profound 14 transformation driven by the interacting forces of climate change and globalization. The Arctic Governance Project is one group examining the role of governance in these transformations and exploring different ways that the Arctic's existing governance systems can maximize a cooperative future. Student Profile: Siberian Food – a Raw Deal Chen Yichao Not for the Fainthearted Doing something new is Professional chef, columnist 21 nothing new for Chinese 16 and TV icon Andreas Viestad Polar Law Student Chen Yichao. shares his experiences with local See how this student of human cuisine during his travels in Western rights lived and learned in the Siberia, and offers a recipe for the Arctic, finding ways of applying region's famous Stroganina dish. his studies to Arctic indigenous peoples. The University of the Arctic Shared Voices Magazine 2010 Editorial Team / Outi Snellman, Lars Kullerud, Scott Forrest, Harry Borlase UArctic International Secretariat Editor in Chief / Outi Snellman University of Lapland Managing Editor / Scott Forrest Box 122 96101 Rovaniemi Finland Editorial Assistant / Harry Borlase [email protected] Graphic Design & Layout / Puisto Design & Advertising / www.puistonpenkki.fi Tel. -

Uarctic Strategic Plan 2020

Strategic Plan 2020 uarctic.org Who We Are Photo James David Broome UArctic (University of the Arctic) was created through an initiative of the Arctic Council (Iqaluit Declaration 1998) and was officially launched in 2001. UArctic is a cooperative network of universities, colleges, research institutes and other organizations concerned with education and research in and about the North. UArctic builds and strengthens collective resources and collaborative infrastructure, thereby enabling member institutions to better serve their constituents and their regions. Cooperation in education, research, outreach and engagement enhances human capacity in the North, promotes Our Vision 5 viable communities and sustainable economies, and engages partners from Our Mission 6 outside the region. Our Values 8 UArctic Strategic Plan 2020 How We Serve the North 12 UArctic International Secretariat University of Lapland Box 122, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland [email protected] Tel. +358-16-341 341 Our 2020 Goals 16 Fax. +358-16-362 941 www.uarctic.org Graphic Design & Layout Background 22 Puisto Design & Advertising Printer Erweko Oy, 2014 Printed on Munken Pure by Arctic Paper Cover 240g/m2, contents 150g/m2 UArctic Strategic Plan 2020 UArctic Strategic Plan 2020 Photo Haukur Sigurðsson An Empowered North – With Shared Voices 4 UArctic Strategic Plan 2020 UArctic Strategic Plan 2020 5 Photo Haukur Sigurðsson Empower the people of the Circumpolar North by providing unique educational and research opportunities through collaboration within a powerful network -

Uarctic : a Partnership for an Empowered North

Outi Snellman IAU Kuala Lumpur 14 November 2018 UArctic : a partnership for an empowered north November 2018 www.uarctic.org Who we are University of the Arctic, UArctic, is a cooperative network of universities, colleges, research institutes and other organizations concerned with education and research in and about the North (204• 204 Members in 2018). UArctic builds and strengthens• Higher Education Institutions collective resources and collaborative infrastructure that enables member and Other Organizations institutions to better serve their • Arctic and Non-Arctic constituents and their regions. members Through cooperation in education, research and outreach we enhance human capacity in the North, promote viable “ communities and sustainable economies, and forge global partnerships. www.uarctic.org IAS 1987 C “The 1990 Bruntland Arctic Commission A Zone of 1987 EU Northern Peace and Dimension Cooperation” Rovaniemi Rovaniemi prosess UArctic Arctic 1998 Environmental Protection Nordic / Strategy: Nordkallott cooperation The Arctic Council 1991 www.uarctic.org The Arctic Council www.uarctic.org www.uarctic.org Empower the people of the Circumpolar North by providing unique educational and research opportunities through collaboration within a powerful network of members. www.uarctic.org • Circumpolar • Inclusive • Reciprocal www.uarctic.org UArctic benefits students, public and private sectors, and the North as a region by creating strong international collaboration among its members that: • Creates shared knowledge, competences and -

Law, Policy and the Promotion of Cooperation

THE 10TH POLAR LAW SYMPOSIUM 2017 13-14 NOVEMBER 2017 ROVANIEMI, ARKTIKUM HOUSE ADDRESS: POHJOISRANTA 4 GLOBAL AND LOCAL GOVERNANCE OF THE POLES: LAW, POLICY AND THE PROMOTION OF COOPERATION PROGRAMME MONDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2017 08.15 REGISTRATION 09.00 - 09.30 WELCOMING WORDS - POLARIUM Mauri Ylä-Kotola, Professor and Rector of the University of Lapland Timo Koivurova, Professor and Director of the Arctic Centre 09.30 - 10.30 KEY NOTE SPEECH – CHAIRED BY PROF. TIMO KOIVUROVA Lars Kullerud, President of the University of the Arctic (UArctic) 10.30 - 11.00 BREAK 11.00 - 12.30 CONCURRENT PANELS PANEL 1 - INDIGENOUS PEOPLES, LAND RIGHTS AND GOVERNANCE ISSUES 11.00 - 12.30 POLARIUM CHAIRED BY DR. DOROTHEE CAMBOU Øyvind Ravna Professor How Norway meets its Faculty of Law, commitments to the Sámi UiT-The Arctic University of under the ILO 169 and the Norway UNDRIP – assessed by the most recent case law Grant Christensen Associate Professor Indigenous taxation of University of North Dakota non-native activity in Alaska: the problem created by Alaska v. native village of Venetie Juris Doctor Candidate Jessica Black Jane Glassco Northern Fellowship Alumni, “We don’t want a brown University of Victoria version of the YTG” in Nän K'ałädàtth'ät Juris Doctor (Changing times, Samantha Dawson Jane Glassco Northern continuing ways) Fellowship Alumni, University of British Columbia Dwight Newman Professor of Law How international law of & Canada Research Chair in the sea issues may Indigenous Rights in constrain Arctic Constitutional and indigenous land rights International Law, University of Saskatchewan Alejandro Fuentes Senior Researcher Human rights protection of Raoul Wallenberg Institute indigenous peoples’ (RWI), Lund claims in the Americas. -

Arctic Centre Insert

ARCTIC Arctic Research Consortium of the United States Member Institution Winter 2006/2007, Volume 12 Number 2 Research at the University of Lapland Arctic Centre stablished in 1979 and located on the Oulu, and Helsinki, and about 50 supervi- EArctic Circle, the University of Lap- sors and associate members from multiple For more information, contact: land in Rovaniemi, Finland, enrolls about institutions. The theme of the school is Riku Lavia 4,300 undergraduate and 400 graduate stu- Social and Environmental Impacts of Arctic Centre dents and employs a staff of 650. Within Modernization and Global Change in the University of Lapland the university, the Arctic Centre was Arctic. ARKTIS students work in the social PO Box 122 established in 1989 as a multidisciplinary sciences—including sociology, political sci- FI-96101 Rovaniemi research institute and science centre. Its ence, environmental politics, international Finland multinational staff of 80 conducts a wide relations, economics, cultural studies, law, [email protected] • 358-16-3412758 range of research and education activities, and education—as well as biology and www.arcticcentre.org carries out project services, and maintains geography. Most research groups at the a science centre, information service, and Arctic Centre also include graduate stu- The Arctic Centre hosts the Finnish library. The operating budget for the Arctic dents who are funded by outside sources, National Secretariat of the International Centre (€2.34 million in 2005) comes such as the Academy of Finland and vari- Polar Year (IPY; see page XX) in coopera- from the Finnish Ministry of Education. ous foundations. tion with the Thule Institute of the Univer- Arctic Centre research projects also receive The Arctic Centre organizes and sity of Oulu. -

Social Policies and Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan

Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki Finland SOCIAL POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN TAIWAN ELDERLY CARE AMONG THE TAYAL I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) DOCTORAL THESIS To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in lecture room 302, Athena, on 18 May 2021, at 8 R¶FORFN. Helsinki 2021 Publications of the Faculty of Social Sciences 186 (2021) ISSN 2343-273X (print) ISSN 2343-2748 (online) © I-An Gao (Wasiq Silan) Cover design and visualization: Pei-Yu Lin Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] ISBN 978-951-51-7005-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-7006-4 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2021 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how Taiwanese social policy deals with Indigenous peoples in caring for Tayal elderly. By delineating care for the elderly both in policy and practice, the study examines how relationships between indigeneity and coloniality are realized in today’s multicultural Taiwan. Decolonial scholars have argued that greater recognition of Indigenous rights is not the end of Indigenous peoples’ struggles. Social policy has much to learn from encountering its colonial past, in particular its links to colonization and assimilation. Meanwhile, coloniality continues to make the Indigenous perspective invisible, and imperialism continues to frame Indigenous peoples’ contemporary experience in how policies are constructed. This research focuses on tensions between state recognition and Indigenous peoples’ -

Mapping an Arctic Policy Framework for the Scottish Government

Briefing Note Arctic connections - Mapping an Arctic policy framework for the Scottish government Tahseen Jafry, Michael Mikulewicz & Sennan Mattar Overview Historically, Scotland and the Arctic have been connected by social and cultural ties. More recently, mainly through trade and tourism, economic links have flourished. Some of this is underpinned by the expanding number of scientific and academic partnerships that have developed between Scotland and its Arctic neighbours. Scotland is also excelling in technological innovation to tackle climate change and in environmental protection. There is no doubt that Scotland has considerable expertise across many sectors and is well placed as a valuable partner in Arctic matters. The development of Arctic Connections - Scottish Government’s Arctic Policy Framework is demonstration of the significance placed on Scottish-Arctic issues in Scotland. This briefing note provides an insight into the mapping exercise carried out for the purposes of the Scottish Government’s Arctic Policy Framework, highlighting key Scottish Arctic relationships, pointing to Scottish strengths across sectors and exploring avenues for even closer cooperation. Mapping Scotland’s existing links with the Arctic region While Scotland is not located within the Arctic Circle, it is among the region’s closest neighbours and shares with Arctic countries a number of features, outlooks and challenges. In light of these similarities and opportunities for mutual cooperation, the Scottish Government has developed its own Arctic Policy Framework. This policy decision emerged from the Scottish Government’s extensive involvement in Arctic fora, including the First Minister’s participation in the Arctic Circle Assembly in 2016 and 2017. It also came in recognition of the mutual policy agendas in the face of climate change and social and economic challenges affecting rural and remote northern communities. -

Arctic Policy &

Arctic Policy & Law References to Selected Documents Edited by Wolfgang E. Burhenne Prepared by Jennifer Kelleher and Aaron Laur Published by the International Council of Environmental Law – toward sustainable development – (ICEL) for the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law (IUCN-CEL) Arctic Policy & Law References to Selected Documents Edited by Wolfgang E. Burhenne Prepared by Jennifer Kelleher and Aaron Laur Published by The International Council of Environmental Law – toward sustainable development – (ICEL) for the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICEL or the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of ICEL or the Arctic Task Force. The preparation of Arctic Policy & Law: References to Selected Documents was a project of ICEL with the support of the Elizabeth Haub Foundations (Germany, USA, Canada). Published by: International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL), Bonn, Germany Copyright: © 2011 International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL) Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL) (2011). -

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: the Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979)

A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979) Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Edited by Christer Westerdahl BAR International Series 2154 2010 Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports Gordon House 276 Ban bury Road Oxford 0X2 7ED England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com BAR S2154 A Circumpolar Reappraisal: The Legacy of Gutorm Gjessing (1906-1979). Proceedings of an International Conference held in Trondheim, Norway, 10th-12th October 2008, arranged by the Institute of Archaeology and Religious Studies, and the SAK department of the Museum of Natural History and Archaeology of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2010 ISBN 978 1 4073 0696 4 Front and back photos show motifs from Greenland and Spitsbergen. © C Westerdahl 1974, 1977 Printed in England by 4edge Ltd, Hockley All BAR titles are available from: Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford 0X2 7BP England [email protected] www.hadrianbooks.co.uk The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com CHAPTER 7 ARCTIC CULTURES AND GLOBAL THEORY: HISTORICAL TRACKS ALONG THE CIRCUMPOLAR ROAD William W. Fitzhugh Arctic Studies Center, Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 2007J-J7072 fe// 202-(W-7&?7;./ai202-JJ7-2&&f; e-mail: fitzhugh@si. -

Sweden's Strategy for the Arctic Region Cover Image Sarek National Park

Sweden's strategy for the Arctic region Cover image Sarek National Park. Photo: Anders Ekholm/Folio/imagebank.sweden.se D Photo: Kristian Pohl/Government Offices of Sweden Sweden is an Arctic country. becoming ever more necessary, especially in the climate and environmental area. We have a particular interest and The EU is an important Arctic partner, responsibility in promoting peaceful, and Sweden welcomes stronger EU stable and sustainable development in the engagement in the region. Arctic. Swedish engagement in the Arctic has for The starting point for the new Swedish a long time involved the Government, the strategy for the Arctic region is an Arctic Riksdag and government agencies, as well in change. The strategy underscores the as regional and local authorities, importance of well-functioning indigenous peoples' organisations, international cooperation in the Arctic to universities, companies and other deal with the challenges facing the region. stakeholders in the Arctic region of The importance of respect for Sweden. international law is emphasised. People, peace and the climate are at the centre of A prosperous Arctic region contributes to Sweden's Arctic policy. our country's security and is therefore an important part of the Government's Changes in the Arctic have led to foreign policy. increased global interest in the region. The Arctic Council is the central forum for cooperation in the Arctic, and Sweden stresses the special role of the eight Arctic states. At the same time, increased Ann Linde cooperation with observers to the Arctic Minister for Foreign Affairs Council and other interested actors is 1 Foreword 1 1. -

Council of the University of the Arctic: Strides in Strategic Development

Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council Narvik, Norway November 28-29, 2007 University of the Arctic International Secretariat University of Lapland Report to the Senior Arctic Officials of the Arctic Council November 2007 Introduction The University of the Arctic (UArctic) is a cooperative network of universities, colleges, and other organizations committed to higher education and research in the North. UArctic constitutes 110 members from around the Arctic; 87 higher education institutions and 33 other organizations. It is now 10 years since the early idea of a University of the Arctic came from a small group of individuals at an AMAP meeting, leading to a proposal to the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs). This proposal envisaged a geographically dispersed institution that would combine the strengths of existing establishments by bringing together students and staff. Benefits would include the sharing of Arctic knowledge, costs of expensive and/or underused facilities, and expanded opportunities for access to education among the region's residents, in particular, for the indigenous peoples of the region. The SAO’s mandated a feasibility study on the University of the Arctic, and the process led to the Iqualuit Declaration of 1998 where the Ministers, "welcome, and are pleased to announce the establishment of the University of the Arctic, a university without walls...". The official Launch of the University of the Arctic occurred in Rovaniemi, Finland, on June 12, 2001, in conjunction with the celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Rovaniemi process. In the years following the Launch, membership has increased steadily and the administrative structures to support governance and programs have been consolidated.