Report on Northern Beaches Suicide Postvention/Prevention Protocol Pilot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing in Greater Western Sydney

CENSUS 2016 TOPIC PAPER Housing in Greater Western Sydney By Amy Lawton, Social Research and Information Officer, WESTIR Limited February 2019 © WESTIR Limited A.B.N 65 003 487 965 A.C.N. 003 487 965 This work is Copyright. Apart from use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part can be reproduced by any process without the written permission from the Executive Officer of WESTIR Ltd. All possible care has been taken in the preparation of the information contained in this publication. However, WESTIR Ltd expressly disclaims any liability for the accuracy and sufficiency of the information and under no circumstances shall be liable in negligence or otherwise in or arising out of the preparation or supply of any of the information WESTIR Ltd is partly funded by the NSW Department of Family and Community Services. Suite 7, Level 2 154 Marsden Street [email protected] (02) 9635 7764 Parramatta, NSW 2150 PO Box 136 Parramatta 2124 WESTIR LTD ABN: 65 003 487 965 | ACN: 003 487 965 Table of contents (Click on the heading below to be taken straight to the relevant section) Acronyms .............................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of key findings ....................................................................................................... 4 Regions and terms used in this report .................................................................................. -

Sydney's North Shore

A CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD RESEARCH PUBLICATION SYDNEY’S NORTH SHORE Office Markets DECEMBER 2017 CITIES INTO ACTION CITIES INTO ACTION CONTENTS MARKET OVERVIEW ......................................3 HIGHLIGHTS ........................................................4 LEASING MARKET ............................................9 INVESTMENT ACTIVITY .................................11 INFRASTRUCTURE IMPROVEMENTS ......12 SUMMARY .......................................................... 13 A CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD RESEARCH PUBLICATION Market Overview Office markets in Sydney’s North Shore comprise the powerhouse suburbs of North Sydney and Macquarie Park, in addition to the smaller hybrid markets of Chatswood, and Crows Nest/St Leonards. Collectively they amount to 2,289,125 sq m – roughly 45% the size of the Sydney CBD. Suburb by suburb as of July 2017 the PCA (Property Council of Australia) recorded 873,693sq m in Macquarie Park, 822,496sq m in North Sydney, 314,017sq m in Crows Nest/St Leonards and 278,919sq m in Chatswood. Collectively these markets Sydney’s comprise of 51% Prime grade office space (Premium and A Grade) and 49% population Secondary grade. (Grade B, C and D). SYDNEY’S is forecast to Major changes to the North Shore urban landscape are anticipated in the years to increase from come with 100 Mount Street (42,000sq m) 5.1 million to due for completion in 2018 and 1 Denison Street (61,000 sq m) due in 2020. From 6.7 million people 2024 both developments will benefit from the Sydney Metro project which will by 2037 see Victoria Cross Station constructed in the heart of North Sydney. Nearby, from 2024 Crows Nest will also benefit from NORTH SHORE a new metro station. From 2019 other stations including Chatswood, North Ryde, Macquarie Park and Macquarie University will benefit from the Norwest Metro project. -

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan

Fresno County Community-Based Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan Written by DeQuincy A. Lezine, PhD and Noah J. Whitaker, MBA For those who struggle, those who have been lost, those left behind, may you find hope… Fresno Cares 2018 Introduction 4 Background and Rationale 5 How Suicide Impacts Fresno County 5 The Fresno County Suicide Prevention Collaborative 7 History 8 Capacity-Building 9 Suicide Prevention in Schools (AB 2246) 10 Workgroups 10 Data 11 Communication 11 Learning & Education 12 Health Care 13 Schools 14 Justice & First Responders 15 Understanding Suicide 16 Overview: the Suicidal crisis within life context 17 The Suicidal Crisis: Timeline of suicidal crisis and prevention 22 Levels of Influence: The Social-Ecological Model 23 Identifying and Characterizing Risk 24 Understanding How Risk Escalates Into Suicidal Thinking 26 Warning Signs: Recognizing when someone may be suicidal 27 Understanding How Suicidal Thinking Turns into Behavior 28 Understanding How a Suicide Attempt Becomes a Suicide 28 Understanding How Suicide Affects Personal Connections 29 Stopping the Crisis Path 30 Comprehensive Suicide Prevention in Fresno County 31 Health and Wellness Promotion 34 Prevention (Universal strategies) 34 Early Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Clinical Intervention (Selective strategies) 35 Crisis Intervention and Postvention (Indicated strategies) 36 Where We are Now: Needs and Assets in Fresno County 37 Suicidal Thoughts and Feelings 37 Suicide Attempts 40 1 Suicide 41 Understanding -

Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention

2018 Community Conversations to Inform Youth Suicide Prevention A STUDY OF YOUTH SUICIDE IN FOUR COLORADO COUNTIES Presented to Attorney General Cynthia H. Coffman Colorado Office of the Attorney General By Health Management Associates 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary..............................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................11 Scope of the Problem........................................................................................................................................................11 Key Stakeholder Interviews...........................................................................................................................................13 Community Focus Groups.............................................................................................................................................. 17 School Policies & Procedures........................................................................................................................................27 Traditional Media & Suicide.......................................................................................................................................... -

Answer Key: Suicide Prevention

Personal Health Series Suicide Quiz Answer Key 1. List four factors that can increase a teen’s risk of suicide: Any four of the following: a psychological disorder, especially depression, bipolar disorder, and alcohol and/or drug use; feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness; previous suicide attempt; family history of depression or suicide; emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; lack of a support network, poor relationships with parents or peers, and feelings of social isolation; dealing with bisexuality or homosexuality in an unsupportive family or community or hostile school environment; perfectionism. 2. True or false: If a person talks about suicide, it means he or she is just looking for attention and won’t go through with it. 3. True or false: The danger of suicide has passed when a person begins to cheer up. 4. List four warning signs that someone is thinking about suicide: Any four of the following: talking about suicide or death in general; hinting he/she might not be around anymore; talking about feeling hopeless or feeling guilty; pulling away from friends or family; writing songs, poems, or letters about death, separation, or loss; giving away treasured possessions; losing the desire to do favorite things or activities; having trouble concentrating or thinking clearly; changing eating or sleeping habits; engaging in risky or self-destructive behaviors; losing interest in school and/or extra-curricular activities. 5. True or false: Once a person is suicidal, he or she is suicidal forever. 6. True or false: Most teens who attempt suicide really intend to die. 7. True or false: If a friend tells you she’s considering suicide and swears you to secrecy, you have to keep your promise. -

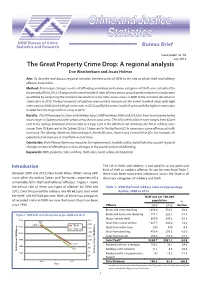

The Great Property Crime Drop: a Regional Analysis

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Bureau Brief Issue paper no. 88 July 2013 The Great Property Crime Drop: A regional analysis Don Weatherburn and Jessie Holmes Aim: To describe and discuss regional variation between parts of NSW in the rate at which theft and robbery offences have fallen. Method: Percentage changes in rates of offending in robbery and various categories of theft were calculated for the period 2000 to 2012. Changes in the extent to which rates of crime across areas have become more similar were quantified by comparing the standard deviation in crime rates across areas in 2000 to the standard deviation in crime rates in 2012. Product moment calculations were used to measure (a) the extent to which areas with high crime rates in 2000 also had high crime rates in 2012 and (b) the extent to which areas with the highest crime rates in 2000 had the largest falls in crime in 2012. Results: The fall in property crime and robbery across NSW between 2000 and 2012 has been very uneven; being much larger in Sydney and other urban areas than in rural areas. The fall in theft offence rates ranges from 62 per cent in the Sydney Statistical Division (SD) to 5.9 per cent in the Northern SD. Similarly, the fall in robbery rates ranges from 70.8 per cent in the Sydney SD to 21.9 per cent in the Northern SD. In some areas some offences actually increased. The Murray, Northern, Murrumbidgee, North Western, Hunter and Central West SDs, for example, all experienced an increase in steal from a retail store. -

Demographic Analysis

NORTHERN BEACHES - DEMOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS FINAL Prepared for JULY 2019 Northern Beaches Council © SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd 2019 This report has been prepared for Northern Beaches Council. SGS Economics and Planning has taken all due care in the preparation of this report. However, SGS and its associated consultants are not liable to any person or entity for any damage or loss that has occurred, or may occur, in relation to that person or entity taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd ACN 007 437 729 www.sgsep.com.au Offices in Canberra, Hobart, Melbourne, Sydney 20180549_High_Level_Planning_Analysis_FINAL_190725 (1) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. OVERVIEW MAP 4 3. KEY INSIGHTS 5 4. POLICY AND PLANNING CONTEXT 11 5. PLACES AND CONNECTIVITY 17 5.1 Frenchs Forest 18 5.2 Brookvale-Dee Why 21 5.3 Manly 24 5.4 Mona Vale 27 6. PEOPLE 30 6.1 Population 30 6.2 Migration and Resident Structure 34 6.3 Age Profile 39 6.4 Ancestry and Language Spoken at Home 42 6.5 Education 44 6.6 Indigenous Status 48 6.7 People with a Disability 49 6.8 Socio-Economic Status (IRSAD) 51 7. HOUSING 53 7.1 Dwellings and Occupancy Rates 53 7.2 Dwelling Type 56 7.3 Family Household Composition 60 7.4 Tenure Type 64 7.5 Motor Vehicle Ownership 66 8. JOBS AND SKILLS (RESIDENTS) 70 8.1 Labour Force Status (PUR) 70 8.2 Industry of Employment (PUR) 73 8.3 Occupation (PUR) 76 8.4 Place and Method of Travel to Work (PUR) 78 9. -

NEEDHELP ATHOME? Lane Cove, Mosman

Live in the Northern Sydney Region? NEED HELP AT HOME? Are you ... There are Commonwealth Home and Community • Aged 65+ (50+ for Aboriginal persons) Care (HACC) services and NSW Community Care • A person with a disability, or Supports Programs (CCSP) in your local area that may • A carer be able to help. Interpreting Service Deaf and hearing impaired Translating & Interpreting Service Telephone Typewriter Service (TTY) �����������1300 555 727 TIS ������������������������������������������������������������������������������13 14 50 Lane Cove, Mosman, North Sydney or Willoughby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People Greek Welfare Centre ................................................................ 9516 2188 Aboriginal Access & Assessment Team ......................... 1300 797 606 CALD/Dementia Aboriginal HACC Development Officer .............................. 9847 6061 HammondCare ........................................................................... 9903 8326 Frail Aged/Dementia Community Care Northern Beaches Ltd ............................ 9979 7677 LNS Multicultural Aged Day Care Program ....................... 9777 7992 Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT) CALD Assessment for community aged care services and residential care St. Catherine’s Aged Care Services ....................................... 8875 0919 Royal North Shore Hospital .................................................... 9462 9333 Dementia UnitingCare Ageing ������������������������������������������������������������� 1800 486 484 Allied Health Frail Aged/Dementia -

Lower Northern Beaches

BUS ROUTE FIVE Lower Northern Beaches Avalon Berowra Ku-ring-gai 4 Chase Mount Ku-ring-gai Newport Dural Mount Colah MONA VALE RD Mona Vale 3 Duffys Forest Asquith Terrey Hills Warriewood Hornsby North Turramurra Waitara ROAD Belrose Wahroonga Warrawee St Ives Turramurra Collaroy Pymble Davidson Frenchs Forest South Turramurra Gordon Gordon East Killara Killara 5 North Curl Curl West Pymble Killarney Heights East Lindfield M2 MWY Lindfield Macquarie Park Seaforth Roseville Castle Cove Willoughby SYDNEY RD North Ryde Chatswood West Ryde Manly Artarmon Northbridge East Ryde St Leonards Gladesville Cammeray Lane1 Cove Northwood Neutral Bay Wollstonecraft Hunters Hill Mosman St Waverton 2 Milsons Point Pymble Ladies’ College is located on 20 hectares of park-like grounds on Sydney’s Upper North Shore 1 Pymble Bus Route One: This College Bus services Lane Cove, Hunters Hill, Boronia Park, East Ryde, Ryde, Macquarie Park and students board and alight within the College grounds. 2 Pymble Bus Route Two: This College Bus services Neutral Bay, Cammeray, Northbridge, Willoughby, Castlecrag, Middle Cove, Castle Cove, East Roseville, right into Eastern Arterial Rd and on through East Lindfield, East Killara and students board and alight within the College grounds. 3 Pymble Bus Route Three: This College Bus services Dural, Glenhaven, Castle Hill (at Oakhill College), West Pennant Hills, Beecroft, Cheltenham (at Cheltenham Girls’ High School), Epping, Marsfield and Macquarie Park (at Macquarie Centre) and students board and alight within the College grounds. 4 Pymble Bus Route Four: This College Bus services Avalon, Newport, Mona Vale, Ingleside, Terrey Hills, Hassall Park and St Ives and students board and alight within the College grounds. -

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents Introduction 4 Demographic Data 7 Population – Northern Sydney 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population 10 Country of birth 12 Languages spoken at home 14 Migration Stream 17 Children and Young People 18 Government schools 18 Early childhood development 28 Vulnerable children and young people 34 Contact with child protection services 37 Economic Environment 38 Education 38 Employment 40 Income 41 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 43 Social Environment 45 Community safety and crime 45 2 Contents Maternal Health 50 Teenage pregnancy 50 Smoking during pregnancy 51 Australian Mothers Index 52 Disability 54 Need for assistance with core activities 54 Housing 55 Households 55 Tenure types 56 Housing affordability 57 Social housing 59 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Northern Sydney district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Northern Sydney district there are nine LGAS: • Hornsby • Hunters Hill • Ku-ring-gai • Lane Cove • Mosman • North Sydney • Northern Beaches • Ryde • Willoughby The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. 4 Northern Sydney District Data Profile The majority of these sources are publicly available. We have provided source statements for each table and graph. -

National Guidelines: Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide

Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force April 2015 Blank page Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines Table of Contents Front Matter Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... i Task Force Co-Leads, Members .................................................................................................................. ii Reviewers .................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ....................................................................................................................................................... iii National Guidelines Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Terminology: “Postvention” and “Loss Survivor” ....................................................................................... 4 Development and Purpose of the Guidelines ............................................................................................. 6 Audience of the Guidelines ........................................................................................................................ -

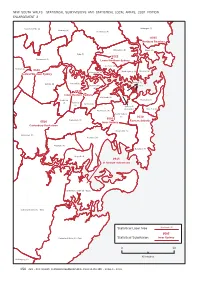

Map 4 from NSW ASGC.Pdf

NEW SOUTH WALES—STATISTICAL SUBDIVISIONS AND STATISTICAL LOCAL AREAS, 2001 EDITION ENLARGEMENT 2 Baulkham Hills (A) Warringah (A) Hornsby (A) Ku-ring-gai (A) 05650565 NorthernNorthern BeachesBeaches Willoughby (C) Manly (A) Ryde (C) 05550555 Parramatta (C) LowerLower NorthernNorthern SydneySydney Lane Cove (A) Holroyd (C) 05400540 05400540 North Sydney (A) Mosman (A) Hunter'sHunter's HillHill (A)(A) CentralCentral WesternWestern SydneySydney SydneySydney (C)(C) -- Auburn (A) Concord (A) Drummoyne InnerInnerInnerInner (A) 05350535 InnerInnerInner WesternWesternWestern SydneySydneySydney LeichhardtLeichhardtLeichhardt (A)(A)(A) Strathfield Woollahra (A) Burwood (A) Ashfield (A) (A) Sydney (C) - Remainder Waverley (A) Marrickville (A) South Sydney (C) 05100510 05050505 Canterbury (C) EasternEastern SuburbsSuburbs 05200520 InnerInnerInner SydneySydneySydney Canterbury-BankstownCanterbury-Bankstown Botany Bay (C) Bankstown (C) Rockdale (C) Hurstville (C) Randwick (C) Kogarah (A) 05150515 StSt George-SutherlandGeorge-Sutherland (Sutherland Shire (A) - East) Sutherland Shire (A) - West Statistical Local Area Leichhardt (A) 05050505 Sutherland Shire (A) - East Statistical Subdivision InnerInnerInner SydneySydneySydney 0 10 Kilometres Wollongong (C) 156 ABS • AUSTRALIAN STANDARD GEOGRAPHICAL CLASSIFICATION • 1216.0 • 2001 NEW SOUTH WALES—STATISTICAL SUBDIVISIONS AND STATISTICAL LOCAL AREAS, 2001 EDITION ENLARGEMENTS Uralla (A) Gilgandra (A) Manilla (A) 35053505 CentralCentral MacquarieMacquarie (excl.(excl. Dubbo)Dubbo) Narromine (A) Dubbo (C)