Enhancing NBN's Value Comparing NBN with Australia's Top 10 Trading Partners and OECD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communication Infrastructure Study for Precise Positioning Services in Regional Queensland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Wang, Charles and Feng, Yanming and Higgins, Matthew and Looi, Mark (2009) Communication infrastructure study for precise positioning services in regional Queensland. In: Proceedings of International Global Navigation Satellite Systems Society Symposium, 1-3 December 2009, Holiday Inn Hotel, Gold Coast, Queensland. © Copyright 2009 [please consult the authors] International Global Navigation Satellite Systems Society IGNSS Symposium 2009 Holiday Inn Surfers Paradise, Qld, Australia 1 – 3 December, 2009 Communication Infrastructure Study for Precise Positioning Services in Regional Queensland Charles Wang Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 1963, [email protected] Yanming Feng Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 1926, [email protected] Matt Higgins Department of Environment and Resource Management +61 7 3896 3754, [email protected] Mark Looi Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 5114, [email protected] ABSTRACT Providing precise positioning services in regional areas to support agriculture, mining, and construction sectors depends on the availability of ground continuously operating GNSS reference stations and communications linking these stations to central computers and users. With the support of CRC for Spatial Information, a more comprehensive review has been completed recently to examine various wired and wireless communication links available for precise positioning services, in particular in the Queensland regional areas. The study covers a wide range of communication technologies that are currently available, including fixed, mobile wireless, and Geo-stationary and or low earth orbiting satellites. -

Annual Report 2011

Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN 2011 ANNUAL REPORT A year of change CONTENTS ABOUT US 1 How the TIO works 1 Board and Council 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE 5 Ombudsman’s overview 5 A year of change 6 Highlights 7 Top trends 2010-11 8 PERFORMANCE 11 Resolving complaints 11 Our organisation 18 Contributing to the co-regulatory environment 22 Creating awareness 23 The Road Ahead 26 TIO IN NUMBERS 27 Complaint statistics 2010–11 27 Top 10 members 32 Complaints by member 37 Timeliness 49 Industry Codes 50 FiNANCiaL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2011 55 Financial report 56 APPENDICES 88 Appendix 1 Systemic issues 1 July 2010- 30 June 2011 88 Appendix 2 List of public submissions made by the TIO 91 Appendix 3 Calendar of outreach activities 93 Appendix 4 Issues by Category 94 Appendix 5 Explanation of TIO data terms 108 1 ABOUT US How the TIO works The Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman is a fast, free and fair dispute resolution service for small business and residential consumers who have a complaint about their telephone or internet service in Australia. We are independent and do not take sides. Our goal is to settle disputes quickly in an objective and non-bureaucratic way. We are able to investigate complaints about telephone and internet services, including by collecting all documentation and information relevant to the complaint. We have the authority to make binding decisions (decisions a telecommunications company is legally obliged to implement) up to the value of $30,000, and recommendations up to the value of $85,000. -

NBN Methodology Report

Mozo Experts Choice Awards NBN Plans 2018 The Mozo Experts Choice Awards recognise products that deliver exceptional value to consumers. They’ve been running since 2014, but this is the first year they’ve been awarded to the best value NBN broadband plans. Product providers don’t pay to be in the running and we don’t play favourites. Our judges base their decision on hard-nosed calculations of value to the consumer, using Mozo’s extensive product database and research capacity. We identify the most important features of each product, group each product into like-for-like comparisons, and then calculate which are better value than most. Winning a Mozo Experts Choice Award means that a product is in the top 10% of products in terms of value for money. ● For product providers, it’s a third-party endorsement of their product. ● For consumers, it’s a sign that a product is among the leaders and is worthy of consideration. This report lists the winners and explains the judging methodology. 1 NBN Plans - 2018 Winners NBN 25 Contract activ8me Sonic ActiveNet Fast AusBBS Standard Harbour ISP Standard myNetFone Standard 25 Spintel Standard Waterfront Networks NBN-25/5 NBN 50 Contract activ8me Super Sonic ActiveNet Faster Belong Standard Plus - Large Exetel Standard Plus Southern Phone Turbo Spintel Plus TPG Fast NBN 100 Contract activ8me HyperSonic ActiveNet Fastest AusBBS Premium Belong Standard Premium - Large Exetel Premium Harbour ISP Standard Plus Southern Phone Max Spintel Premium 2 NBN 25 No Lock-in ActiveNet Fast AusBBS Standard Aussie -

Submission 32

Productivity Commission Inquiry TELECOMMUNICATIONS UNIVERSAL SERVICE OBLIGATION Victorian Farmers Federation Submission July 2016 The Victorian Farmers Federation The Victorian Farmers Federation (VFF), Australia’s largest state farmer organisation and only recognised consistent voice on issues affecting rural Victoria, welcomes the opportunity to comment on the telecommunications USO. Victoria is home to 25 per cent of the nation’s farms. They attract neither government export subsidies nor tariff support. Despite farming on only three per cent of Australia’s available agricultural land, Victorians produce 30 per cent of the nation’s agricultural product. The VFF represents the interests of our State’s dairy, livestock, grains, horticulture, flowers, chicken meat, pigs and egg producers. The VFF consists of a nine person Board of Directors, with seven elected members and two appointed directors, a member representative General Council to set policy and eight commodity groups representing dairy, grains, livestock, horticulture, chicken meat, pigs, flowers and egg industries. Farmers are elected by their peers to direct each of the commodity groups and are supported by Melbourne-based staff. Each VFF member is represented locally by one of the 230 VFF branches across the state and through their commodity representatives at local, district, state and national levels. The VFF also represents farmers’ views on hundreds of industry and government forums. Peter Tuohey President Victorian Farmers Federation Farrer House 24 Collins Street Melbourne 3000 p 1300 882 833 f 03 9207 5500 e [email protected] w www.vff.org.au Contact: Hannah Lewis Policy Officer Introduction USO – a stagnant agreement in a rapidly evolving market USO reform is crucial to the growth of Australian Agriculture and development of rural communities. -

Jtde V8n2 Jun20 Whole of Issu

Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy JTDE Volume 8, Number 2, June 2020 Table of Contents Editorial The Digital Economy Lights Up ii Leith H Campbell Public Policy Enhancing NBN's Value 1 Richard Anthony Ferrers Ultra-fast Broadband: The New Zealand Experience 31 Murray Owen Milner Fighting Pandemics By Exploiting 5G, AI and Bigdata Enabled Technologies 146 David Soldani An Analysis of China’s Proposal to Control and Centrally Manage the Internet 159 Alan Dupont Articles RDTD: A Tool for Detecting Internet Routing Disruptions at AS-Level 18 Bahaa Al-Musawi, Mohammed Falih Hassan, Sabah M. Alturfi The 1-Millisecond Challenge – Tactile Internet: From Concept to Standardization 56 Duc Tran Le, Tri Gia Nguyen, Thi Thu Thao Tran Digital Trust Gap 94 Gwangjae Kim, Jee Young Lee The Effect of Social Media Regulatory Content Law in Indonesia 110 Taufik Hidayat, Rahutomo Mahardiko Mobile Technologies, Financial Inclusion, and Inclusive Growth in East Indonesia 123 Miguel Angel Esquivias, Lilik Sugiharti, Ari Dwi Jayanti, Rudi Purwono, Narayan Sethi History of Australian Telecommunications Army Communications Looking Ahead 167 Simon Moorhead Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, ISSN 2203-1693, Volume 8 Number 2 June 2020 Copyright © 2020 i Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy The Digital Economy Lights Up Editorial Leith H. Campbell Deputy Managing Editor Adjunct Professor, RMIT University Abstract: The effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the digital economy has been profound. How and whether the widespread adoption of teleworking, telehealth and remote learning will continue after the crisis subsides is a matter for policy debate. Digital inclusion will, in any case, be important. -

Motivating and Retaining Local Government Workers: What Does It Take?

Motivating and retaining local government workers: what does it take? Robyn Morrisa a School of Law and Justice, Faculty of Business and Law, Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Abstract. The capacity of local government to recruit appropriately qualified staff, motivate employees to give their best effort, and keep voluntary staff turnover low directly affects council operational performance. In addition, high staff turnover increases staffing costs and results in a loss of skill and know-how to the organisation. Yet for many years now local government managers have expressed concerns about their capacity to find, motivate and retain suitably qualified staff. This ability is critical to public service success and reform, thus needs to be a high priority if local government is to meet the challenges of the 21st century. This paper presents the findings of a rigorous empirical study that formed part of a larger research program. Data was collected from 500 employees in 12 metropolitan, regional/ rural Western Australian local governments. It examines what factors affect three critical workplace outcomes – job satisfaction, worker willingness to exert discretionary effort, and turnover intentions – all of which have important implications for workforce planning and development. The findings provide useful and usable knowledge for improving our understanding of employee motivation and retention in the public service. From a practical perspective it can enhance public sector manager capacity to maximise the potential of human resources recruited by offering a framework of mechanisms through which managers can influence employee discretionary work effort and retention. By creating an attractive place of employment local governments can better retain staff and build a greater pool of talent from which to choose. -

2012 Annual Report

Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN 2012 ANNUAL REPORT PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE CONTENTS ABOUT US 1 COMPLAINT STATISTICS 16 ENGAGEMENT 32 About the TIO 1 Dashboard 16 Awareness of TIO services 32 Ombudsman’s message 2 New Complaints by quarter 16 Resilient Consumers 32 New Complaints v. concilations TIO Talks 32 Board Chairman’s message 3 and investigations 16 First online annual report 32 Council Chairman’s message 4 New complaints by consumer type 16 Accessibility 32 New complaints by service type 17 A new website 32 Board and Council in 2011-12 5 Conciliations and Investigations Community engagement 33 Board members in 2011-12 5 by service type 17 Council members in 2011-12 8 Top 7 issues in new complaints 17 Industry engagement 34 Trends overview 18 Account management model 34 Ombudsman roadshow 34 PERFORMANCE 11 Complaints about the “big three” service providers 18 MNews 34 Conciliation 11 Complaints about mobile phone Our membership 34 services 18 Live transfers 11 Government and regulation 34 Small business complaints 19 Conciliation snapshot 11 Highlights 34 Increase in enquiries 19 List of submissions 35 Timeliness 12 Geographical trends 20 Consumer satisfaction Australia wide 20 ORGANISATION 36 with TIO services 12 Victoria 21 Feedback about the TIO 12 South Australia 21 Staff overview 36 Amendments to the Australian Capital Territory 22 New teams 36 TIO Constitution 13 New South Wales 22 TIO organisational structure 36 Queensland 23 Wellness program 36 Monetary limits 13 Western Australia -

Inquiries Into NBN Access Pricing and Wholesale Service Standards

Inquiries into NBN access pricing and wholesale service standards Final report November 2020 accc.gov.au Australian Competition and Consumer Commission 23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of: the Commonwealth Coat of Arms the ACCC and AER logos any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold copyright, but which may be part of or contained within this publication. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC, GPO Box 3131, Canberra ACT 2601. Important notice The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain professional advice if you have any specific concern. The ACCC has made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding the accuracy, currency or completeness of that information. Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy prior to publication. -

Adam Internet Pty Ltd, Aussie Broadband Pty Ltd, Iinet Limited, and Internode Pty Ltd

Public inquiry to make final access determinations for the declared fixed line services Submission by Herbert Geer Lawyers on behalf of: Adam Internet Pty Ltd, Aussie Broadband Pty Ltd, iiNet Limited, and Internode Pty Ltd 3 June 2011 Bris_Docs 1347878 6743687 v1 1 1. INTRODUCTION This submission is made on behalf of Adam Internet Pty Ltd, Aussie Broadband Pty Ltd, iiNet Limited and Internode Pty Ltd (collectively, our Clients ) in response to the discussion paper of April 2011 entitled Public inquiry to make final access determinations for the declared fixed line services ( Discussion Paper ). Collectively, our Clients themselves or through their subsidiaries - i.e. Chime Communications (iiNet), Agile (Internode) and Wideband Networks (Aussie Broadband) - acquire a substantial share of the declared services provided over Telstra’s fixed network. Over the last five years, each of them has been forced to notify the ACCC of numerous access disputes about the declared services in order to obtain reasonable terms of access from Telstra. The form of the Final Access Determinations ( FADs ) are therefore extremely important to each of them. Amendments that were made by the Telecommunications Legislation Amendment (Competition and Consumer Safeguards) Act 2010 have resulted in a move from a negotiate/arbitrate regulatory access model to a model where the ACCC is given power to set terms and conditions of access upfront. Under this new model, the setting of terms and conditions upfront is done by means of Access Determinations. The changes to the access regime model have coincided with a shift in the ACCC’s thinking regarding the underlying methodology that it uses to set access prices. -

Communications Sector Market Study Final Report April 2018

Communications Sector Market Study Final report April 2018 accc.gov.au ACCC communications sector market study final report Consumers are getting better value, but there is considerable concentration in key service markets. MOBILE PHONE NBN 3.1% 4.5% real decline in real decline in prices prices in 2016-17 in 2016-17 49% 24% in data quotas in in data quotas in 2016-17 2016-17 89% 94% of services supplied of services supplied by three providers in 2017 by four providers in 2017 The NBN is more than half way through its rollout however for some consumer segments wireless may increasingly be a viable substitute. AVAILABLITY POTENTIAL SUBSTITUTES NBN available 100GB+ to 6.3 million Download quotas on premises with 3.6 some wireless plans have million activations reached over 100GB by March 2018 Regional Australians have been among the 30% of fixed broadband first to benefit from the subscribers would consider NBN with 56% of switching to a wireless activations in regional service Australia Some immediate NBN issues are being tackled. $$$ NBN 50Mbps ACCC inquiry into ACMA imposing 37% increase in CVC and CVC NBN wholesale rules to improve between September and capacity price service standards NBN consumer December 2017 promotion experience There is rapid growth and development of emerging services and also some potential issues to monitor. 80% of Over $1b Industry predicts Industry predicts businesses used Australian data content delivery the Internet of cloud computing centre market networks will carry Things will provide in 2016 in 2017 approximately 70% significant uplift to of all trac by 2021 GDP by 2025 OTT services continuing to While e-SIMs may increase transform use of communications competition between mobile networks and disrupt markets service providers there may be barriers for smaller providers in oering e-SIM devices Fixed and wireless networks will continue to evolve, influenced by technology, new services, consumer preferences and government policy. -

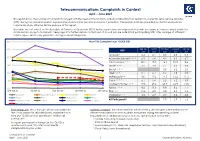

Telecommunications Complaints in Context April – June 2021

Telecommunications Complaints in Context April – June 2021 This report shows the number of complaints lodged with the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman in relation to a specific retail service provider (RSP), during the relevant quarter, expressed as a ratio of the number of services it provided. Complaints data are provided by the Ombudsman to Communications Alliance for the purpose of this report. The ratios are not exact, as the definition of Services in Operation (SIOs) for this report does not align precisely with the range of services about which the Ombudsman accepts complaints. See page 2 for further details on this topic. It should also be noted that participating RSPs offer a range of different service types, which may generate varying levels of complaints. 30.0 New TIO Complaints per 10,000 SIO Apr-Jun Jul-Oct Oct-Dec Jan-Mar Apr-Jun 25.0 RSP 2020 2020 2020 2021 2021 1 amaysim 0.6 0.4 0.3 0.5 0.3 20.0 1, 2, 3, 4 Aussie Broadband 6.9 5.4 4.5 6.3 6.9 1, 2, 3, 4 Commander 20.4 15.7 16.1 10.9 8.6 15.0 1, 2, 3, 4 Dodo 5.2 2.9 2.1 3.5 3.8 Exetel1, 2, 3, 4 3.0 3.2 2.6 10.0 iiNet1, 2, 3, 4 11.1 6.7 5.7 5.8 4.9 MyRepublic2, 4 18.1 17.2 14.5 12.2 11.5 5.0 Optus1, 2, 3, 4 6.1 5.4 5.2 5.2 3.9 1, 2, 3, 4 Southern Phone 19.8 27.6 23.7 22.9 14.8 1, 2, 3, 4 0.0 Telstra 8.6 11.1 9.8 9.5 7.1 APR -JUN 20 JUL-SEP 20 OCT-DEC 20 JAN-MAR 21 APR-JUN 21 TPG1, 2, 4 10.6 4.8 3.8 4.0 3.6 amaysim Aussie Broadband Commander Dodo Vodafone1, 2, 4 3.5 2.9 2.7 3.0 2.8 Exetel iiNet MyRepublic Optus All Participants* 7.0 6.9 5.3 Southern Phone Telstra TPG Internet Vodafone All participants* *All Participants: This is the sum of new complaints to Services Provided : The chart identifies which of the 4 service types listed below an RSP the Ombudsman for all participants, expressed as a offered to residential or small business consumers during the reporting quarter. -

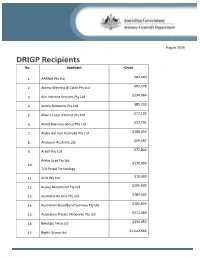

DRIGP Recipients No

August 2016 DRIGP Recipients No. Applicant Grant $82,440 1. AARNet Pty Ltd $83,378 2. Access Wireless & Cable Pty Ltd $294,084 3. Ace Internet Services Pty Ltd $85,200 4. Acurix Networks Pty Ltd $77,102 5. Albury Local Internet Pty Ltd $37,792 6. Allied Business Group Pty Ltd $180,000 7. Alpha Dot Net Australia Pty Ltd $69,387 8. Amaysim Australia Ltd $72,800 9. Area9 Pty Ltd Atthis Sept Pty Ltd $132,000 10. T/A Portal Technology $10,000 11. Arris Pty Ltd $265,600 12. Aussie Broadband Pty Ltd $184,000 13. Australia On Line Pty Ltd $265,600 14. Australian Broadband Services Pty Ltd $373,080 15. Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd $334,050 16. Bendigo Telco Ltd $1,042,666 17. BigAir Group Ltd Grant No. Applicant $48,000 18. Bitwave Networks Pty Ltd $32,408 19. BIZCOM (NT) Pty Ltd $81,719 20. Blast Technologies Pty Ltd $80,800 21. Blue Apache Pty Ltd $30,400 22. Blue Net Pty Ltd $133,600 23. BorderNet Internet Pty Ltd $96,320 24. Brennan Voice and Data Pty Ltd $2,201,006 25. Broadband Solutions Pty Ltd $128,510 26. BT Business Pty Ltd $190,763 27. BT Residential Pty Ltd $30,519 28. BT Trade Pty Ltd $28,318 29. BT Utilities Pty Ltd $26,000 30. C2A internet.com.au Pty Ltd $36,010 31. Call Dynamics Pty Ltd $196,800 32. Central Data Systems Pty Ltd $439,200 33. CipherTel Pty Ltd $18,800 34. Cirrus Communications Pty Ltd Clear Technology Ptd Ltd $161,600 35.