Communications Sector Market Study Final Report April 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommunications Infrastructure Support Guide

Telecommunications Infrastructure Support Guide Making the most of the nbn and the Mobile Black Spot Program First Edition — October 2016 A NSW Government Initiative Front Cover: Ed Fagan, Cowra Address & Contact Details Photo: Kate Barclay Suite 4, 59 Hill Street First Edition published in 2016 by Regional Development Australia (PO Box 172) Central West, Orange, NSW. ORANGE NSW 2800 02 6369 1600 This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair use as permitted under the Copyright www.rdacentralwest.org.au Act 1968, no part may be produced by any process without permission from the publisher. All For any questions relating to this guide or the information Rights Reserved. contained herein, please feel free to contact RDA Central West and we will endeavour to provide assistance where possible. Disclaimer: Information provided in this publication is intended as a general reference and is provided About Regional Development Australia Central West in good faith. It is made available on the understanding that Regional Development Australia RDA Central West is a Commonwealth and State funded not-for- Central West is not engaged in rendering professional advice. profit organisation responsible for the economic development and long term sustainability of the NSW Central West region. Regional Development Australia Our organisation is overseen by a Committee of dedicated local Central West makes no leaders who possess a wide cross section of professional skills and statements, representations, or warranties about the accuracy experience. or completeness -

TPG Telecom Limited and Its Controlled Entities ABN 46 093 058 069

TPG Telecom Limited and its controlled entities ABN 46 093 058 069 Annual Report Year ended 31 July 2016 2 TPG Telecom Limited and its controlled entities Annual report For the year ended 31 July 2016 Contents Page Chairman’s letter 3 Directors’ report 5 Lead auditor’s independence declaration 34 Consolidated income statement 35 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 36 Consolidated statement of financial position 37 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 38 Consolidated statement of cash flows 39 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 40 Directors’ declaration 91 Independent auditor’s report 92 ASX additional information 94 3 TPG Telecom Limited and its controlled entities Chairman’s letter For the year ended 31 July 2016 Dear Shareholders On behalf of the Board of Directors, I am pleased to present to you the TPG Telecom Limited Annual Report for the financial year ended 31 July 2016 (“FY16”). Financial Performance FY16 was another successful year for the Group. Continued organic growth and the integration of iiNet into the business have resulted in further increases in revenue, profits and dividends for shareholders. FY16 represents the eighth consecutive year that this has been the case. A detailed review of the Group’s operating and financial performance for the year is provided in the Operating and Financial Review section of the Directors’ Report starting on page 7 of this Annual Report, and set out below are some of the key financial highlights and earnings attributable to shareholders from the year. FY16 FY15 Movement Revenue ($m) 2,387.8 1,270.6 +88% EBITDA ($m) 849.4 484.5 +75% NPAT ($m) 379.6 224.1 +69% EPS (cents/share) 45.3 28.2 +61% Dividends (cents/share) 14.5 11.5 +26% iiNet Acquisition At the beginning of FY16 we completed the acquisition of iiNet and consequently there has been significant focus during the year on integrating the businesses to improve the efficiency of the combined organisation. -

Amaga 2020 Individual.Pdf

Tax invoice Membership category Payment details ABN 83 048 139 955 Membership Form Regular (Loyalty) Concession* (Loyalty) Membership Fee $ (inc of GST) (inc of GST) + Networks $ Individual □ $180 ($162) □ $90 ($81) + Donation* $ Your information Individual (existing Total Payable $ New member ICOM members only) □ $171 ($153) □ $86 ($76.50) □ Australian Museums and Galleries Association AMaGA Membership Card * Donations over $2.00 are tax deductible. □ Renewing member Individual employed by a member - Australian Museums and Galleries Association □ $144 ($144**) Member number (if known) AMaGA □ Membership Card institution Individual employed Payment method AMaGA by a member Please email or post your completed form for payment □ Please send me a new membership card □ $144 ($144**) - Member Number institution (existing New members will automatically get sent a card. Expiry processing. Your receipt and membership card or sticker will be Member Name AMaGA is a partner to ICOM members only) Renewing members will receive a sticker with your Australian AMaGA Museums ICOM Australia. and Galleries If found, please return to Association PO Box 24, Deakin West receipt/invoice to attach to your current card. Member ACT 2600 issued when payment has been processed. * Concession rates available to retired, full-time students, pensioners, unemployed Member Number Expiry Member Name and volunteers Australian AMaGA is a partner to Museums ICOM Australia. and Galleries If found, please return to Association PO Box 24, Deakin West Member ACT 2600 made payable to Australian Museums and Galleries Association ** Discounts are capped at 20% □ Cheque Title □ Mr □ Miss □ Ms □ Mrs □ Dr □ Name Loyalty Discount Members of more than five consecutive years can claim a 10% loyalty Credit Card (Visa or Mastercard only) discount on their membership. -

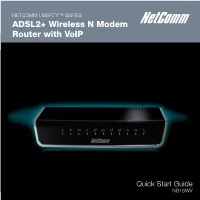

ADSL2+ Wireless N Modem Router with Voip

NETCOMM LIBERTY™ SERIES ADSL2+ Wireless N Modem Router with VoIP Quick Start Guide NB16WV 1Hardware Installation The router has been designed to be placed on a desktop. All of the cables exit from the rear for better organization. The LED indicator display is visible on the front of the router to provide you with information about network activity and the device status. See below for an explanation of each of the indication lights. FRONT PANEL ICON COLOUR STATE DESCRIPTION Power Blue Off The NB16 is powered off Flashing The NB16 is currently starting up On The NB16 is powered on ADSL Sync Blue Off A connection via an ADSL service is not currently configured Flashing Connecting to an ADSL service On Connected via an ADSL service 3G Signal Blue Off A connection via 3G is not currently configured or no 3G dongle found Flashing Connecting to a 3G service On Connected via a 3G service Red Flashing 3G connection failed, attempting to connect again On SIM Error Internet Connection N/A Off An Internet connection is not currently configured Blue Flashing Traffic via the ADSL connection On Connected via an ADSL service Red Flashing Traffic via the 3G connection On Connected via a 3G service Purple Flashing Traffic via the WAN connection On Connected via an internet service supplied via the WAN port ETH 1, 2, 3, 4 Blue Off No device is connected via the LAN port - Flashing Traffic on LAN port On Device connected via the LAN port WAN Blue Off No device connected via the WAN port On Device connected via the WAN port WiFi Blue Off WiFi is disabled Flashing WPS PBC connection available On WiFi is enabled VoIP Blue Off VoIP is not configured Flashing Connecting to VoIP service On VoIP connection registered ** Please note that all lights will flash simultaneously if a firmware upgrade takes place. -

Iinet Opens New Broadband Front with 4G Launch

iiNet opens new broadband front with 4G launch 9 October 2012: iiNet, Australia’s leading challenger telco, today opens up new opportunities for growth by launching a range of high-speed 4G wireless broadband services over the Optus LTE network. iiNet will use these high-speed wireless broadband services to win new business and drive up its product-to-customer ratio – leveraging both existing brands and its acquisition of Internode earlier this year. The new 4G plans and products are backed by iiNet’s great customer service, and will continue to evolve, with new features such as unmetered broadband content via tailored 4G plans to be offered next year. iiNet Chief Product Officer, Steve Harley, said iiNet was entering the 4G market early because of strong customer demand. “The move from 3G to 4G services is comparable to moving from first- generation broadband to ADSL2+,” Mr Harley said. “That makes 4G a disruptive force in the market, which is great for iiNet as a challenger brand. With today’s launch, we offer Australia’s most affordable standalone 4G broadband service for just $29.95 a month, plus iiNet-branded 4G devices to make it easy for our customers to use these new services.” "Our range of 4G plans is great; with large data quotas that let both business and residential customers rapidly transfer large files and easily access rich content services.” “iiNet’s 4G services complement our core products, ADSL and fibre broadband, fixed line voice, mobile voice and data services, plus our great fetchtv IPTV service. As well as winning new customers, 4G will drive iiNet’s growth by increasing the number of products we sell each customer.” “Next year, we’ll deliver 4G wireless broadband as Layer 2 network services giving us greater control. -

Infrastructure Report 90-102 Regent Street Redfern, Wee Hur Student Housing

INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT 90-102 REGENT STREET REDFERN, WEE HUR STUDENT HOUSING 02 OCTOBER 2020 CONTACT KAKOLI DAS National Discipline Leader M 0428 981 326 Arcadis E [email protected] Level 16, 580 George Street Sydney NSW 2000 i WEE HUR GROUP WEE HUR STUDENT VILLAGE Infrastructure Report Author Benjamin Fogerty Checker Kakoli Das Approver Kakoli Das Report No F001 - 10036797 Date 25/09/2020 Revision Text 02 This report has been prepared for Wee Hur in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment for Redfern Student Accommodation. Arcadis Australia Pacific Pty Limited (ABN 76 104 485 289) cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. REVISIONS Approved Revision Date Description Prepared by by 01 25/09/2020 Draft Issue BF KD 02 02/10/2020 DA Submission BF KD iii CONTENTS 1 . EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Authority ............................................................................................................................... 1 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Site Information ................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Description -

Security Information Supplied by Australian Internet Service Providers

Edith Cowan University Research Online Australian Information Security Management Conference Conferences, Symposia and Campus Events 11-30-2010 Security Information Supplied by Australian Internet Service Providers Patryk Szewczyk Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ism Part of the Information Security Commons DOI: 10.4225/75/57b677a334789 8th Australian Information Security Mangement Conference, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia, 30th November 2010 This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ism/100 Proceedings of the 8th Australian Information Security Management Conference Security Information Supplied by Australian Internet Service Providers Patryk Szewczyk secau – Security Research Centre School of Computer and Security Science Edith Cowan University Perth, Western Australia [email protected] Abstract Results from previous studies indicate that numerous Internet Service Providers within Australia either have inadequately trained staff, or refuse to provide security support to end-users. This paper examines the security information supplied by Internet Service Providers on their website. Specifically content relating to securing; a wireless network, an ADSL router, and a Microsoft Windows based workstation. A further examination looked at the accuracy, currency, and accessibility of information provided. Results indicate that the information supplied by Internet Service Providers is either inadequate or may in fact further deter the end-user from appropriately securing their computer and networking devices. Keywords ADSL routers, wireless networking, computer security, Internet Service Providers, end-users INTRODUCTION Internet Service Providers (ISPs) often ship ADSL routers preconfigured with the client’s username and password thus eliminating the difficulty faced by novice computer users in accessing the Internet. -

ASX/Media Release

ASX/Media Release 29 March 2017 Sale of Investment in Macquarie Telecom Group Vocus Group Limited (ASX: VOC, ‘Vocus’) today announces that it has disposed of 3,358,511 shares representing ~16% relevant interest in the ordinary shares of Macquarie Telecom Group Limited (ASX: MAQ). The shares were held via a total return swap as described in the FY16 Vocus financial statements. Attached is the Form 605 Notice of ceasing to be a substantial holder. ENDS For further information please contact: Kelly Hibbins Investor Relations Debra Mansfield Corporate Communications P: +61 2 8316 9856 P: +61 3 9674 6569 M: +61 414 609 192 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] About Vocus: Vocus Group (ASX: VOC) is a vertically integrated telecommunications provider, operating in the Australian and New Zealand markets. The Company owns an extensive national infrastructure network of metro and back haul fibre connecting all capital cities and most regional centres across Australia and New Zealand. Vocus infrastructure now connects directly to more than 5,500 buildings. Vocus owns a portfolio of brands catering to corporate, small business, government and residential customers across Australia and New Zealand. Vocus also operates in the wholesale market providing high performance, high availability and highly scalable communications solutions which allow service providers to quickly and easily deploy new services for their own customer base. For more information please go to our website www.vocusgroup.com.au. VOCUSGROUP.COM.AU 605 page 1/2 15 July 2001 Form 605 Corporations Act 2001 Section 671B Notice of ceasing to be a substantial holder To Company Name/Scheme ACN/ARSN 1. -

Perth Public Hearing Transcript

__________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS UNIVERSAL SERVICE OBLIGATION MR P LINDWALL, Presiding Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT PERTH ON TUESDAY, 14 FEBRUARY 2017 AT 8.43 AM Telecommunications 14/02/17 1 © C’wlth of Australia INDEX Page MR BRUCE BEBBINGTON 4-7, 88 MIDWEST DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION MR ROBERT SMALLWOOD 17-31 SHIRE OF CUBALLING MR GARY SHERRY 32-37 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AUSTRALIA WHEATBELT MS JULIET GRIST 37-46, 87-88 MEMBER FOR AGRICULTURAL REGION THE HON. MARTIN ALDRIDGE MLC 46-55 GREAT NORTHERN TELECOMMUNICATIONS MR ANDREW MANGANO 55-63 SHIRE OF COOROW MR TED JACK 63-73, 86-87 WA DEPARTMENT OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT MR KEVIN LEE 73-76 ISOLATED CHILDREN’S PARENTS’ ASSOCIATION WA MS ELYCE DONAGHY 76-78 WHEATBELT BUSINESS NETWORK MS AMANDA WALKER 79-86 TELSTRA MR BOYD BROWN 89 SHIRE OF WESTONIA MR JAMIE CRIDDLE 89-90104-106 Telecommunications 14/02/17 2 © C’wlth of Australia MR LINDWALL: Good morning. Welcome to the public hearings for the Productivity Commission inquiry into the Telecommunications Universal Service Obligation. My name is Paul Lindwall and I am the Commissioner for the inquiry. I would like to start off with a few housekeeping matters. In the event of an emergency, Travelodge Hotel staff will direct or assist people in evacuating and moving to the Assembly points. We will be breaking for morning tea at around 11 am. We look like we will be concluding the hearing around 1 pm. If you have any particular questions, or wish to present at this hearing, please see PaoYi here at the back, who can arrange you to present or make a statement. -

Communication Infrastructure Study for Precise Positioning Services in Regional Queensland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Wang, Charles and Feng, Yanming and Higgins, Matthew and Looi, Mark (2009) Communication infrastructure study for precise positioning services in regional Queensland. In: Proceedings of International Global Navigation Satellite Systems Society Symposium, 1-3 December 2009, Holiday Inn Hotel, Gold Coast, Queensland. © Copyright 2009 [please consult the authors] International Global Navigation Satellite Systems Society IGNSS Symposium 2009 Holiday Inn Surfers Paradise, Qld, Australia 1 – 3 December, 2009 Communication Infrastructure Study for Precise Positioning Services in Regional Queensland Charles Wang Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 1963, [email protected] Yanming Feng Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 1926, [email protected] Matt Higgins Department of Environment and Resource Management +61 7 3896 3754, [email protected] Mark Looi Queensland University of Technology, Australia +61 7 3138 5114, [email protected] ABSTRACT Providing precise positioning services in regional areas to support agriculture, mining, and construction sectors depends on the availability of ground continuously operating GNSS reference stations and communications linking these stations to central computers and users. With the support of CRC for Spatial Information, a more comprehensive review has been completed recently to examine various wired and wireless communication links available for precise positioning services, in particular in the Queensland regional areas. The study covers a wide range of communication technologies that are currently available, including fixed, mobile wireless, and Geo-stationary and or low earth orbiting satellites. -

An Open Briefing Interview With

Company: StarHub Title: Q1 2018 Results Date: 3 May 2018 Time: Start of Transcript Jeannie Ong: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to StarHub's first quarter 2018 results announcement briefing call. My name is Jeannie and it is my pleasure to welcome both the media and investment community to join us at this call. Let me first introduce our panel of speakers. We have a special guest star tonight in the form and shape of Terry Clontz, our Chairman, together with Dennis Chia, our CFO; Dr Chong Yoke Sin, our Chief of Enterprise Business Group; and Howie Lau, our Chief Marketing Officer. We have also invited our Chief Technology Officer, Siew Loong, to join us on the call. With that, let me invite Terry to say a few words to all of us. Terry Clontz: Good evening. So it's been about a year since I've had the opportunity to address you in an earnings call, so I'm delighted to be here. But I want to make it very clear I'm not crossing the line, I'm not an executive; I'm still a non- executive director. But I thought under the circumstances it would be good to start the call and just tell you a little bit about the incoming CEO, Mr Peter Kaliaropoulos. We call him Peter K because some of us have difficulty saying his last name. He's an Australian with 35 years of highly relevant experience in our industry. He's led teams in the fixed, wireless and integrated telco space. -

Consumers' Telecommunications Network

Consumers’ Telecommunications Network Consumer Research: Expectations and Experiences with Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) March 2006 Enquiries: (02) 9572 6007 [email protected] Unit 2, 524-532 Parramatta Road Petersham, NSW 2049 Acknowledgements The Consumers’ Telecommunications Network’s representation of residential and other consumers’ interests in relation to telecommunications issues is supported by the Commonwealth through the ‘Grants to fund Telecommunications Consumer Representations’ program of the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Ryan Sengara, CTN’s Project Officer, was primary author and researcher, and was assisted by Teresa Corbin, CTN’s Executive Director, Sarah Wilson, CTN’s Policy Officer, and Annie McCall, CTN’s Information Officer. CTN would like to acknowledge the contributions made by its Council members: Robin Wilkinson (Tasmanians with Disabilities), Lola Mashado (Australian Financial Counselling & Credit Reform Association), Jack Crosby, Myra Pincott (Country Womens’ Association Australia), Nicholas Agocs (Ethnic Communities Council of WA), Nan Bosler (Australian Seniors Computer Clubs Association), Len Bytheway, Stephen Gleeson (Community Information Strategies Australia Inc.), Ross Kelso (Internet Society of Australia), Maureen Le Blanc (Australian Council of Social Services), and Darrell McCarthy (Better Hearing Australia). CTN would also like to acknowledge the time volunteered by CTN members and other VoIP users who helped to develop and complete the survey. - 2 - Consumers’