Nurdin: Disaster 'Caliphatization'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin and Spread of the Jawi Script

Sub-regional Symposium on the Incorporation of the Languages of Asian Muslim Peoples into the Standardized Quranic Script 2008 ﻧﺪﻭﺓ November 7-5 ﺷﺒﻪ ,Kuala Lumpur ﺇﻗﻠﻴﻤﻴﺔ ,(SQSP) ﺣﻮﻝ:Project ﺇﺩﺭﺍﺝ ﻟﻐﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﺸﻌﻮﺏ ﺍﻹﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ ﰲ ﺁﺳﻴﺎ ﰲ ﻣﺸﺮﻭﻉ ﺍﳊﺮﻑ ﺍﻟﻘﺮﺁﱐ 7_9 ﺫﻭ ﺍﻟﻘﻌﺪﺓ 1429 ﻫـ ﺍﳌﻮﺍﻓﻖ 5-7 ﻧﻮﻓﻤﱪ 2008 ﻡ ﻗﺎﻋﺔ ﳎﻠﺲ ﺍﻷﺳﺎﺗﺬﺓ : ﺍﳉﺎﻣﻌﺔ ﺍﻹﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻌﺎﳌﻴﺔ ﲟﺎﻟﻴﺰﻳﺎ THE ORIGIN AND SPREAD OF THE JAWI SCRIPT Amat Juhari Ph.D Bangi, Malaysia Sub-regional Symposium on the Incorporation of the Languages of Asian Muslim Peoples into the Standardized Quranic Script Project (SQSP), Kuala Lumpur, 5-7 November 2008 THE ORIGIN AND THE SPREAD OF THE JAWI SCRIPT SYNOPSIS This paper discusses the origin and the spread of the Jawi Script. Jawi Script is derived from the Arabic Script, but it later changed its name to Jawi because in Jawi Script there are six more new letters being added to it to represent the six Malay phonemes which are not found in the Arabic Language. The oldest known Jawi writing is the Terengganu Inscriptions dated 24 th February 1303 or 702 Hijrah. Later on Jawi Script was used extensively in the Sultanate of Malacca, the Sultanate of Old Johor, the Sultanate of Aceh, the Sultanate of Johor-Riau and other sultanates and kingdoms of South East Asia. Jawi Script had spread from Aceh in North Sumatra in the west to Ternate and Tidore in the Moluccas Islands in the eastern part of Indonesia, and then from Cambodia in the north to Banten in the south. Nowadays, about 16,000 Malay Jawi manuscripts are being preserved and kept in many libraries and archives around the world. -

The Institutionalisation of Discrimination in Indonesia

In the Name of Regional Autonomy: The Institutionalisation of Discrimination in Indonesia A Monitoring Report by The National Commission on Violence Against Women on The Status of Women’s Constitutional Rights in 16 Districts/Municipalities in 7 Provinces Komnas Perempuan, 2010 In the Name of Regional Autonomy | i In The Name of Regional Autonomy: Institutionalization of Discrimination in Indonesia A Monitoring Report by the National Commission on Violence Against Women on the Status of Women’s Constitutional Rights in 16 Districts/Municipalities in 7 Provinces ISBN 978-979-26-7552-8 Reporting Team: Andy Yentriyani Azriana Ismail Hasani Kamala Chandrakirana Taty Krisnawaty Discussion Team: Deliana Sayuti Ismudjoko K.H. Husein Muhammad Sawitri Soraya Ramli Virlian Nurkristi Yenny Widjaya Monitoring Team: Abu Darda (Indramayu) Atang Setiawan (Tasikmalaya) Budi Khairon Noor (Banjar) Daden Sukendar (Sukabumi) Enik Maslahah (Yogyakarta) Ernawati (Bireuen) Fajriani Langgeng (Makasar) Irma Suryani (Banjarmasin) Lalu Husni Ansyori (East Lombok) Marzuki Rais (Cirebon) Mieke Yulia (Tangerang) Miftahul Rezeki (Hulu Sungai Utara) Muhammad Riza (Yogyakarta) Munawiyah (Banda Aceh) Musawar (Mataram) Nikmatullah (Mataram) Nur’aini (Cianjur) Syukriathi (Makasar) Wanti Maulidar (Banda Aceh) Yusuf HAD (Dompu) Zubair Umam (Makasar) Translator Samsudin Berlian Editor Inez Frances Mahony This report was written in Indonesian language an firstly published in earlu 2009. Komnas Perempuan is the sole owner of this report’s copy right. However, reproducing part of or the entire document is allowed for the purpose of public education or policy advocacy in order to promote the fulfillment of the rights of women victims of violence. The report was printed with the support of the Norwegian Embassy. -

MJT 28-1 Full OK

Melanesian Journal of Theology 28-1 (2012) MANSINAM: CENTRE OF PILGRIMAGE, UNITY, AND POLARISATION IN WEST PAPUA1 Uwe Hummel Dr Uwe Hummel is a pastor of the Evangelical-Lutheran church, and, since April, 2010, has served as Lecturer in Theology at the Lutheran Highlands Seminary in Ogelbeng, near Mt Hagen Papua New Guinea. In previous years, he served as Coordinator of the German West Papua Netzwerk (2004-2009), and as Asia Secretary of the United Evangelical Mission (2007-2010). INTRODUCTION Annually, on February 5, especially in every round fifth year, thousands of pilgrims populate the tiny island of Mansinam in the Dorehri Bay in the Regency of Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia. While the mainly Protestant Christians commemorate the arrival of the first missionaries in 1855, the local hotel industry has its peak season. Coming from Manokwari town on the mainland – some having travelled from neighbouring Papua New Guinea,2 or farther abroad – the pilgrims reach Mansinam by traditional canoe in less than 30 minutes. Because an islet of 450 hectares is not very well suited to accommodate thousands of people, the worshippers, often including the governors, and other VIPs, of 1 The author presented this paper in abbreviated form on June 23, 2011, during the Inaugural Conference of the Melanesian Association of Theological Schools (MATS), held from June 21-24, at the Pacific Adventist University in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. A special word of gratitude goes to Mr Wolfgang Apelt, librarian at the Archive of the Rhenish Mission/United Evangelical Mission (UEM) in Wuppertal Germany, who provided the author with some of the bibliographical data. -

Mei 2019 Edisi 9 1 Journal of Islamic Law Studies, Center of Islamic And

Mei 2019 Edisi 9 ADAT INSTITUTIONS IN ACEH GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE Yunani Abiyoso, Ali Abdillah, Ryan Muthiara Wasti, Ghunarsa Sujatnika and Mustafa Fakhri All Authors are Lecturer at Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia Corresponding author email: [email protected] Acknowledgement This paper based on research titled “Adat Constitution in Indonesia: Analysis on Form of Government in Aceh in Indonesia Constitutional System”, funded by Research Grant Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia, 2017. Abstracts The existence of adat (customary law) in Indonesia becomes a source of value for the survival of the nation. Each region in Indonesia has different adat that can be used as a reference for the form of governmental system in Indonesia. The 1945 Constitution has recognized the existence of adat government that consisting of various forms of adat that have been adopted long before the 1945 Constitution existed. The existence of adat cannot be separated from national and Islamic values. This research was conducted to find out form of adat institution in Aceh and how the integration of such adat governance in local government system based into national law. Thus, to achieve the objectives, this study was conducted by normative juridical research method with historical approach and comparison with other indigenous peoples in Indonesia. Keywords: constitution; adat government; Aceh INTRODUCTION Adat (custom) in Indonesia is an integral part of the national constitutional system. Adat became the forerunner of the existence of this state since the character of the nation is formed from customs that have been built by each region. Adat in every region in Indonesia varies, usually in accordance with the values left by the ancestors in the region. -

The Tradition of Tahlilan on Ternate Society Burhan1, Asmiraty2 1,2Lecturer at the Ternate State Islamic Institute, Dufa-Dufa Ternate Utara

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 6(03): 5347-5354, 2019 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v6i3.02 ICV 2015: 45.28 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2019, THEIJSSHI Research Article The Tradition of Tahlilan on Ternate Society Burhan1, Asmiraty2 1,2Lecturer at the Ternate State Islamic Institute, Dufa-dufa Ternate Utara: Abstract: This study aims to analyze the implementation of tahlilan, society perspective towards this tradition, and the factors of the tahlilan existence on Ternate community. The study was designed in the form of qualitative descriptive research by applying field research, teological normative, and socio-cultural approaches. The data were collected through interview and documentation. The result showed that tahlilan for Ternatenese is nothing but the momentum where family, relatives, friends, and surrounding communities gather to recite some hayyibah sentences (hamfdalah, takbir, shalawat, tasbih), Qur’an verses, dhikr, and other prayers. Ternate society believes that tahlilan is crucial as a medium of da’wah. There are many positive benefits felt by the people of Ternate such as psychological, social, economic, and importantly religious awareness. In religion side, tahlilan is a minfestation of love for Islam and the cultivation of the monotheism concept. The development of understanding and awareness in Muslim religion also lead to a process of evaluation and change in the implementation of tahlilan. In this case, Islamic da'wah succeeds in influencing the socio-cultural life of Ternate community. The tahlilan tradition can exist til now because it is considered to still have coherence with Islamic values, customs and culture. Ternate society still hope that the tradition of tahlilan will last forever. -

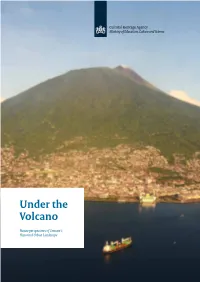

Under the Volcano

Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Under the Volcano Future perspectives of Ternate’s Historical Urban Landscape Report of the Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Kota Ternate, 24-28 September 2012 Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Students of Universitas Khairun: Abdul Malik Pellu Arie Hendra Dessy Prawasti Ikbal Akili Irfan Jubbai Marasabessy Kodradi A.K. Sero Sero Rosmiati Hamisi Surahman Marsaoly Members of Ternate Heritage Society: Azwar Ahmad A. Fachrudin A.B. M. Diki Dabi Dabi Ridwan Ade Colophon Department: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Project name: Ternate Conservation and Development Workshop Version: 1.0 Date: July 2016 Contact: Jean-Paul Corten [email protected] Authors: Jean-Paul Corten, Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands Maulana Ibrahim, Universitas Khairun, Ternate, Indonesia Photo’s: Maulana Ibrahim Cover image: The Island of Ternate seen from the air (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) Design: En Publique, Utrecht Print: Xerox/OTB, The Hague © Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amersfoort 2016 Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands P.O.Box 1600 3800 BP Amersfoort the Netherlands culturalheritageagency.nl/en Content 1. Introduction 7 2. Historical Urban Landscapes 9 3. Past developments 11 4. Present situation 15 Urban quality 15 Technical condition 16 Current use 18 Strengths and weaknesses 18 5. Future perspectives 21 Development opportunities and risks 21 Restoration need 22 Participating students of the Khairun University (Maulana Ibrahim 2012) 6 — Map of Northern Maluku 1. -

Pengaruh Peradaban Islam Di Papua PENGARUH PERADABAN ISLAM DI PAPUA

M. Irfan Mahmud Pengaruh Peradaban Islam di Papua PENGARUH PERADABAN ISLAM DI PAPUA M. Irfan Mahmud (Balai Arkeologi Jayapura) Research on Islamic civilization in Papua has been implemented since 1996. Starting with limited exploration in the area of Raja Ampat Sorong regency. Then proceed in Fak-Fak regency and Kaimana. Study conducted found that the influence of Islamic civilization was stimulated by trade dynamics, especially the Islamic empire in the Moluccas, the Kingdom of Ternate and Tidore. In its development, the kingdom of Tidore absolute power and give a big hand in the formation of Islamic civilization color via satellite countries in the Bird’s Head region along the surrounding islands to colonial entered. Many archaeological remains indication, other than oral sources and the tradition continues. Archaeological remains were found, including the mosques, tombs, pottery, ceramics, religious symbols, and ancient manuscripts. This paper will focus the discussion on three things: (1) a review of Islamic civilization studies conducted Jayapura Archeology, particularly the constraints and problems that still contain the debate to date, (2) the elements of Islamic civilization are essential, such as cultural character and government (petuanan), network scholars, and elements of material culture, and tradition, (3) Islamic cultural traditions inherited colored Muslim communities in certain pockets on the coast. Thirdly it is expected to provide information and research results that will be developed within the framework of the Islamic era in Papua theme. Key words: Islamic influence, Islam Cultural, Papua Latar Belakang Kerajaan-kerajaan (petuanan) di Papua dalam konteks jaringan Islamisasi dan perdagangan, tampak sebagai halaman belakang dengan meletakkan wilayah Aceh sebagai serambinya. -

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio. -

From Paradise Lost to Promised Land: Christianity and the Rise of West

School of History & Politics & Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies (CAPSTRANS) University of Wollongong From Paradise Lost to Promised Land Christianity and the Rise of West Papuan Nationalism Susanna Grazia Rizzo A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) of the University of Wollongong 2004 “Religion (…) constitutes the universal horizon and foundation of the nation’s existence. It is in terms of religion that a nation defines what it considers to be true”. G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on the of Philosophy of World History. Abstract In 1953 Aarne Koskinen’s book, The Missionary Influence as a Political Factor in the Pacific Islands, appeared on the shelves of the academic world, adding further fuel to the longstanding debate in anthropological and historical studies regarding the role and effects of missionary activity in colonial settings. Koskinen’s finding supported the general view amongst anthropologists and historians that missionary activity had a negative impact on non-Western populations, wiping away their cultural templates and disrupting their socio-economic and political systems. This attitude towards mission activity assumes that the contemporary non-Western world is the product of the ‘West’, and that what the ‘Rest’ believes and how it lives, its social, economic and political systems, as well as its values and beliefs, have derived from or have been implanted by the ‘West’. This postulate has led to the denial of the agency of non-Western or colonial people, deeming them as ‘history-less’ and ‘nation-less’: as an entity devoid of identity. But is this postulate true? Have the non-Western populations really been passive recipients of Western commodities, ideas and values? This dissertation examines the role that Christianity, the ideology of the West, the religion whose values underlies the semantics and structures of modernisation, has played in the genesis and rise of West Papuan nationalism. -

A Stigmatised Dialect

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT Zulfadli Bachelor of Education (Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia) Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) Thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide December 2014 ii iii iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT i TABLE OF CONTENTS v LIST OF FIGURES xi LIST OF TABLES xv ABSTRACT xvii DECLARATION xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxi CHAPTER 1 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Preliminary Remarks ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Acehnese society: Socioeconomic and cultural considerations .......................... 1 1.2.1 Acehnese society .................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 Population and socioeconomic life in Aceh ......................................... 6 1.2.3 Workforce and population in Aceh ...................................................... 7 1.2.4 Social stratification in Aceh ............................................................... 13 1.3 History of Aceh settlement ................................................................................ 16 1.4 Outside linguistic influences on the Acehnese ................................................. 19 1.4.1 The Arabic language.......................................................................... -

ISLAMIC NARRATIVE and AUTHORITY in SOUTHEAST ASIA 1403979839Ts01.Qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page Ii

1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page i ISLAMIC NARRATIVE AND AUTHORITY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page ii CONTEMPORARY ANTHROPOLOGY OF RELIGION A series published with the Society for the Anthropology of Religion Robert Hefner, Series Editor Boston University Published by Palgrave Macmillan Body / Meaning / Healing By Thomas J. Csordas The Weight of the Past: Living with History in Mahajanga, Madagascar By Michael Lambek After the Rescue: Jewish Identity and Community in Contemporary Denmark By Andrew Buckser Empowering the Past, Confronting the Future By Andrew Strathern and Pamela J. Stewart Islam Obscured: The Rhetoric of Anthropological Representation By Daniel Martin Varisco Islam, Memory, and Morality in Yemen: Ruling Families in Transition By Gabrielle Vom Bruck A Peaceful Jihad: Negotiating Identity and Modernity in Muslim Java By Ronald Lukens-Bull The Road to Clarity: Seventh-Day Adventism in Madagascar By Eva Keller Yoruba in Diaspora: An African Church in London By Hermione Harris Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia: From the 16th to the 21st Century By Thomas Gibson 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page iii Islamic Narrative and Authority in Southeast Asia From the 16th to the 21st Century Thomas Gibson 1403979839ts01.qxd 10-3-07 06:34 PM Page iv ISLAMIC NARRATIVE AND AUTHORITY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA © Thomas Gibson, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. -

The Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam As a Constructive Power

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 11 [Special Issue – August 2011] The Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam As A Constructive Power Mehmet Ozay1 1Faculty of Education Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 81310 Skudai, Johor Bahru, Malaysia Phone: +60 12 64 77 125 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract This paper argues that the Sultanate of Aceh had commenced a watershed apparently in its relation with the centre of Islamic world to construct a new political concept of Pan-Islamism in the very early decades of the 16th century and as its succession in the 19th century. The mutual relationship between the center and its periphery shares substantive responsibility in a manner of being constructive. Concerning the inter-relational approach between the centre and its periphery of Islamic world, the relation of Aceh with the Ottoman State became one of the hallmarks of the development of Pan-Islamism. Thus this article reexamines the ways in which Acehnese sultans’ promoting Pan-Islamist ideology in relation with the Ottoman State on the basis of contemporary news and commentaries in the journal of Basiret which was published for about 60 news commencing before the appalling Dutch war until June 1874 in Constantinople. Key Words: Pan-Islamism, Basiret, Ottoman, Indian Ocean, Aceh 1.Introduction This paper revisits not only the relationships between the Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam and the Ottoman State but also and the conceptual development of the Pan-Islamic world view in the context of the center and the periphery of Islamic world. The writer employs an approach that is an alternative view to the conventional understanding of center-periphery relations in terms of Islamic states, and the relations between the Ottoman State and the Sultanate of Aceh Darussalam.