"Lady Bird" Johnson Interview XXVII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp WALTER HELLER ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW II PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G. McComb, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G. McComb, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADNINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interviews of Walter W. Heller In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter· set forth, I, Walter W. Heller of Minneapolis, Minnesota do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title and interest in the tape record- ings and transcripts of the personal interviews conducted on February 20, 1970 and December 21,1971 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and prepared for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. This assignment is subject to the following terms and conditions: (1) The edited transcripts shall be available for use by researchers as soon as they have been deposited in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. (2) The tape recordings shall not be available to researchers. (3) During my lifetime I retain all copyright in the material given to the United States by the terms of this instrument. Thereafter the copyright in the edited transcripts shall pass to the United States Government. -

Oral History Interview – JFK#6, 4/10/1966 Administrative Information

Myer Feldman Oral History Interview – JFK#6, 4/10/1966 Administrative Information Creator: Myer Feldman Interviewer: Charles T. Morrissey Date of Interview: April 10, 1966 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 51 pages Biographical Note Feldman, (1914 - 2007); Legislative assistant to Senator John F. Kennedy (1958-1961); Deputy Special Counsel to the President (1961-1964); Counsel to the President (1964- 1965), discusses counting votes and meeting with delegates at the Democratic National Convention, the Texas delegation, and choosing Lyndon B. Johnson as vice president, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed January 8, 1991, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

Lobster 70 Winter 2015

Winter 2015 Lobster ● A fly’s eye view of the American war against Vietnam: 40 years later: who won which war? by Dr T. P. Wilkinson ● Holding Pattern by Garrick Alder 70 ● Last post for Oswald by Garrick Alder ● Paedo Files: a look at the UK Establishment child abuse network by Tim Wilkinson ● The View from the Bridge by Robin Ramsay ● Is this what failure looks like? Brian Sedgemore 1937–2015 by Simon Matthews ● Tittle-Tattle by Tom Easton ● The Gloucester Horror by Garrick Alder ● Tokyo legend? Lee Harvey Oswald and Japan by Kevin Coogan ● Inside Lee Harvey Oswald’s address book by Anthony Frewin Book Reviews ● Blair Inc., by Francis Beckett, David Hencke and Nick Kochan, Reviewed by Tom Easton ● Thieves of State, by Sarah Chayes, Reviewed by John Newsinger ● The Henry Jackson Society and the degeneration of British Neoconservatism, by Tom Griffin, Hilary Aked, David Miller and Sarah Marusek, Reviewed by Tom Easton ● Chameleo: A strange but true story of invisible spies, heroin addiction and Homeland Security, by Robert Guffey, Reviewed by Robin Ramsay ● Blacklisted: The Secret War between Big Business and Union Activists, by Dave Smith and Phil Chamberlain, Reviewed by Robin Ramsay ● Nixon’s Nuclear Specter, by William Burr and Jeffrey P. Kimball, Reviewed by Alex Cox ● Knife Fights: A Memoir of Modern War in Theory and Practice, by John A Nagl, Reviewed by John Newsinger ● The Unravelling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq, by Emma Sky, Reviewed by John Newsinger ● Secret Science: A Century of Poison Warfare and Human Experiments, by Ulf Schmidt, Reviewed by Anthony Frewin ● The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination, by Lamar Waldron, Reviewed by Anthony Frewin ● Without Smoking Gun: Was the Death of Lt. -

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the 1964 Presidential Elections' Visser-Maessen, Laura

We Didn't Come For No Two Seats: The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the 1964 Presidential Elections' Visser-Maessen, Laura Citation Visser-Maessen, L. (2012). We Didn't Come For No Two Seats: The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the 1964 Presidential Elections'. Leidschrift : Struggles Of Democracy, 27(September), 93-113. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72999 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/72999 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Artikel/Article: We Didn’t Come For No Two Seats: The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the 1964 Presidential Elections Auteur/Author: Laura Visser-Maessen Verschenen in/Appeared in: Leidschrift, 27.2 (Leiden 2012) 93-112 Titel Uitgave: Struggles of Democracy. Gaining Influence and Representation in American Politics © 2012 Stichting Leidschrift, Leiden, The Netherlands ISSN 0923-9146 E-ISSN 2210-5298 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden No part of this publication may be gereproduceerd en/of vermenigvuldigd reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de transmitted, in any form or by any means, uitgever. electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Leidschrift is een zelfstandig wetenschappelijk Leidschrift is an independent academic journal historisch tijdschrift, verbonden aan het dealing with current historical debates and is Instituut voor geschiedenis van de Universiteit linked to the Institute for History of Leiden Leiden. Leidschrift verschijnt drie maal per jaar University. Leidschrift appears tri-annually and in de vorm van een themanummer en biedt each edition deals with a specific theme. -

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library the Association for Diplomatic Studies and T

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Service Lyndon Baines Johnson Library The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training oreign Affairs Oral History Pro$ect WALT ROSTOW Interviewed by: Paige E. Mulhollan Initial interview date: March 21, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Early Impressions of Johnson Liberal interests in government Jack (ennedy)s assessment (ennedy chooses Johnson as running mate Eisenhower-Ni,on relations (ennedy-Johnson working relations Johnson on health-poverty worldwide issues Johnson)s Berlin speech - .90. Eisenhower on Johnson)s support State Department - Policy Planning Council .90.-.900 Contacts with President Johnson Policy issues in Johnson)s State of 1nion message -.902 3Plan Si,4 North (orea bombing issue Rostow memo 5.9047 on 8ietnam 9hite House - National Security Council 5NSC7 .905 NSC-State relations - Johnson initiatives Relations with Rusk 3Press leaks4; Restructuring NSC NSC personnel NSC relations with Department Joint Chief of Staff relations President Johnson)s Attributes Considerate of staff E,plosive over leaks Highest standards in job Mrs. Johnson)s influence 1 Relations with Heads of State Master of details Articulate Johnson-de Gaulle relations oreign Policy Issues 9hite House originates initiatives Interdepartmental Regional Groups 5IRGs7 Planning Council central 3Is 1.S. over e,tended4 issue President Johnson)s initiatives ECA E 5Economic Commission for Asia and ar East7 Asian Development Bank President Johnson)s Honolulu speech Speech writers President Johnson)s speech-making President Johnson - Rusk coordination Pan American Highway President Johnson)s relations with Bill Moyers Personnel 3Tuesday lunch4 meetings 8ietnam and President (ennedy Goodpaster memo on 8ietnam disintegration Laos crisis (ennedy-(hrushchev 8ienna meeting Domino theory Choice of 8ietnam for fight Rostow-(ennedy relationship Cuban missile crisis 8ietnam crisis 1.S. -

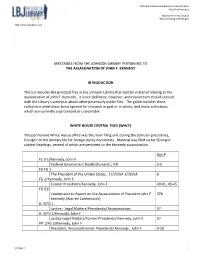

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

All the Way Study Guide

Official Study Guide Welcome to All the Way! We are excited to share with you the official study guide for All the Way, a new political drama by Robert Schenkkan coming to Broadway in spring 2014. All the Way examines “accidental President” Lyndon B. Johnson’s first year in office, covering his fight to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and to win election in his own right. Featuring a cast of 20 actors portraying historical figures both famous and infamous, Schenkkan’s play vividly brings to life a crucial turning point in American history. Inside this guide, you’ll find a slate of articles, activities, and other resources that will help you use All the Way as a teaching tool to deepen students’ understanding of the historic and political issues at play in 1964, as well as the process of adapting history into drama. The resources in this guide are organized into three sections, each with a unique focus: The Turning Point, covering Lyndon Johnson and the legislative process; We Shall Overcome, covering the Civil Rights Movement in the critical year of 1964; and Living History, covering the process of bringing history to the stage. Each section contains introductory articles, discussion questions, and a complete lesson plan for an activity designed to actively engage students in the material. At the beginning of each section, you’ll find a Lesson Overview with suggestions for teaching the section as a complete lesson; however, we encourage you to mix and match the resources in each section to create your own arts-integrated curriculum for All the Way. -

Document Title: Civilrights-Introduction

Lyndon B. Johnson and Civil Rights: Introduction to the Digital Edition Kent B. Germany Associate Professor of History, University of South Carolina Nonresident Research Fellow, Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia On 22 November 1963, at approximately 2:38 P.M. (CST), Lyndon B. Johnson stood in the middle of Air Force One, raised his right hand, and inherited the agenda of an assassinated president.1 Cecil Stoughton’s camera captured that morbid scene in black-and-white photographs that have become iconic images in American history. Three days after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. suggested to the new president that “one of the great tributes that we can pay in memory of President Kennedy is to try to enact some of the great, progressive policies that he sought to initiate.” President Johnson promised that he would not “give up an inch” and that King could “count on” his commitment.2 Seven and a half months later, on 2 July 1964, Johnson sat at a table in the East Room of the White House and signed the Civil Rights Act. Reverend King and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy were among the several dozen politicians and civil rights activists crowded together to witness the event in person, while a national audience watched the event live on television. Forged from years of grassroots organizing and political maneuvering, this legislation would eventually force the dismantling of Jim Crow, the approximately seventy-year-old system of racial segregation in the United States. The bill gave the federal government the power to desegregate public accommodations, fight against workplace discrimination, speed up public school desegregation, mediate racial disputes, and restrict several other discriminatory practices. -

Foreign Policy, Barry Goldwater and the 1964 Presidential Election

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1995 To defeat a maverick: Foreign policy, Barry Goldwater and the 1964 presidential election Jeffreys J Matthews University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Matthews, Jeffreys J, "To defeat a maverick: Foreign policy, Barry Goldwater and the 1964 presidential election" (1995). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 466. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/jp68-hapm This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a iy type of conq)uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quali^ of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and in^roper alignment can adverse^ affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send U M I a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these w ill be noted. -

Did Lyndon Johnson Betray the Civil Rights Movement?

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Summer 8-1999 The Civil Rights President and the MEDP Dispute: Did Lyndon Johnson Betray the Civil Rights Movement? Heath Andrew Clark University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Clark, Heath Andrew, "The Civil Rights President and the MEDP Dispute: Did Lyndon Johnson Betray the Civil Rights Movement?" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/294 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - PROSPECTUS ~ame: _j~f_~~~ ____ ~~£:~_______________ _ College: J1...£:.h..:!._2Q€:!::!-q~J.___ Oep art men t: __ .;f,;k<.:..y____________ _ Facul ty Mentor: _~j)L __ s..)e::jl!~_&~Lccd________________ _ PROJECT TITLE: __ ~-:IA~__ CLLe.:stJL-tl1.g~J-fL~.i.--S~---- __H-e.. __ A!~QI.._::.: __ iJ/~t?~jc.~-.i);..J.-J=i.L2d~~--l)j~.::.~~~·~'--&6:c£.-- . ' f --:::>_, jf,:.e__ ~ jl--'-5il~--jl~~L'l:;g""',.L-~------ ___ ________ _ PROJECT DESCRIPTION (Attach not more than one additional page, if necessary): Projected Signed: <"--.-----~-"' ..................................................................................................... III .......... f; ..................... .. I have discussed this research proposal with this student and agree to serve in an advisory role, as f ul mentor, and to certif t accepta" of the completed project. -

George Reedy Interview

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp GEORGE E. REEDY ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW XXV PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, George E. Reedy Oral History Interview XXV, 8/7/90, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, George E. Reedy Oral History Interview XXV, 8/7/90, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. INTERVIEW XXV DATE: August 7, 1990 INTERVIEWEE: GEORGE REEDY INTERVIEWER: Michael L. Gillette PLACE: Mr. Reedy's office, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Tape 1 of 1, Side 1 G: You also described last time the circumstances of your assuming the role of press secretary. And you indicated how much of your job was actually administrative, the logistics of getting the press where they needed to be, et cetera. Let me ask you to elaborate on that. R: That's a very important point. The press secretary, if he does his job properly, is going to spend more of his time on administrative work than on any other single thing, because the basic point here is to see that the press has access to the president, or at least access to presidential thinking and presidential strategy and plans and what have you. If it were solely and simply a spokesman's job, it would be easy. All you would have to do would be to keep up with what's going on and just tell the press. -

James H. Blundell Interviewer: William Hartigan Date of Interview: February 18, 1976 Location: Washington, D.C

James H. Blundell, Oral History Interview – 2/18/1976 Administrative Information Creator: James H. Blundell Interviewer: William Hartigan Date of Interview: February 18, 1976 Location: Washington, D.C. Length: 25 pages Biographical Note Blundell, a Texas political figure, friend of Lyndon B. Johnson, and member of the Democratic National Committee in 1960, discusses Johnson’s 1960 presidential primary campaign and vice-presidential campaign, as well as the relationship between Johnson and John F. Kennedy, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form.