Andy's Lost ... Or, Sharing and Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

Adrift from Home and Neglected by International Law

Adrift From Home and Neglected By International Law: Searching for Obligations to Provide Climate Refugees with Social Services Nathan Stopper Student Note – Columbia Journal of Transnational Law Supervised Research Paper – Professor Michael Gerrard 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………… 3 I. Climate Change and Its Effects on SIDS ………………………………... 6 A. The Basic Science of Climate Change ………………………………. 6 B. The Effect of Climate Change on SIDS ……………………………... 9 II. Social Services Climate Refugees Will Need to Adapt and Survive in a New State …………………………….……………………………….. 12 III. Possible Sources of Obligations to Provide Social Services In International Law ……………………………………………………….. 15 A. Refugee Treaties ……………………………………………………. 15 1. The 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol ………………. 17 2. Regional Accords: The OAU Convention and the Cartagena Declaration ……………………………………… 20 B. Customary International Law ………………………………………. 22 1. Customary Human Rights Law …………………………….. 25 2. Customary Laws Specific to Refugees …………………….. 28 Conclusion …………………………….……………………………….. 31 3 Introduction There is indisputable evidence that anthropogenic climate change is causing the planet to warm and the oceans to rise.1 Some of the myriad challenges presented by rising temperatures and waters have already begun to occur, while others may need more time to make themselves felt. Unfortunately, many of the states and people least responsible for the levels of climate changing greenhouse gas emissions will suffer the most severe consequences. Increased flooding -

Will & Grace Data Report

SQAD REPORT: HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS PAGE: 1 WILL & GRACE DATA REPORT HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS SQAD REPORT: HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS PAGE: 2 [pronounced skwäd] For more than 4 decades, SQAD has provided dynamic research & planning data intelligence for advertisers, agencies, and brands to review, analyze, plan, manage, and visualize their media strategies around the world. ADVERTISING RESEARCH ANALYTICS & PLANNING SQAD REPORT: HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS PAGE: 3 ABOUT THIS REPORT WILL & GRACE REPORT: HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS DATA SOURCE: SQAD MediaCosts: National (NetCosts) Our Data SQAD Team has pulled historical cost data (2004-2006 season) for the NBC juggernaut, Will & Grace to see where the show was sitting for ad values compared to the competition; and to see how those same numbers would compete in the current TV landscape. The data in this report is showing the AVERAGE :30sec AD COST for each of the programs listed, averaged across the date range indicated. When comparing ad costs for shows across different years, ad costs for those programs have been adjusted for inflation to reflect 2017 rates in order to create parity and consistency. IN THIS REPORT: 2004-2005 Comedy Programming Season Comparison 4 2005-2006 Comedy Programming Season Comparison 5 2004-2006 Comedy Programming Trend Report 6 Comedy Finale Episode Comparison 7 Will & Grace -vs- 2016 Dramas & Comedies 8-9 Will & Grace -vs- 2017 Dramas & Comedies 10-11 SQAD REPORT: HISTORICAL UNIT COST ANALYSIS PAGE: 4 WILL & GRACE V.S. TOP SITCOMS ON MAJOR NETWORKS - 04/05 SEASON Reviewing data from the second to last season of Will & Grace, we see that among highest rated sitcoms on broadcast TV of the time, Will & Grace came out on top for average unit costs for a 30 second ad during the Fall 2004 season. -

Harbour Rentals

Harbour Rentals, LLC 5793 CAPE HARBOUR DRIVE SUITE 122 CAPE CORAL, FL 33914 Please Fill Out All Five Pages and Click Submit at bottom CREDIT CARD AUTHORIZATION FORM Please complete all fields. CREDIT CARD INFORMATION CARD TYPE: MasterCard VISA Discover AMEX Other ____________________________ CARDHOLDER NAME (as shown on card) _______________________________________________ CARD NUMBER: ___________________________________________________ EXPIRATION DATE ( mm/yy): ___________________________ SECURITY CODE: _________________ CARDHOLDER ZIP CODE (from credit card billing address) _______________________ Email Address I, ______________________________________, authorize Harbour Rentals, LLC to charge my credit card for any charges related to the Boat Rental including those fees under the Standard Boat Rental Agreement and also the Boat Rental Damage Expense Listing. I understand that my information will be saved to file for future transactions on my account. $1,000.00 for security deposit, in the event of damages to the boat or lost items until we can evaluate the costs and come to an agreement on total cost to you. Any amount below $1,000.00 will be credited back to you. Harbour Rentals LLC. is authorized to send e-mails with special offers and promotions and is allowed to take my photos regarding my experience with them to be used for posts on Facebook, Instagram and other Social Media platform. Customer Signature_____________________________________ Date_____________ Harbour Rentals, LLC Boat Rentals LESSEE TO READ THIS AGREEMENT BEFORE SIGNING THIS DOCUMENT. In consideration of the agreement herein, Harbour Rentals, LLC (herein after referred to as the LESSOR) agrees to lease to the undersigned (herein after referred to as the LESSEE) the vessel and equipment as described herein. -

September 2019 Commodore Phil Davies

September 2019 Commodore Phil Davies [email protected] It seems hard to believe that September is already upon us, hopefully you have all enjoyed the summer and perhaps more importantly had time to get out on the water and visit the club. At this point the club is gearing up for the Annual meeting, our nominations committee is concluding its work and our Board will review the 2020 budget at our September Board meeting. Over the summer there have been many events to celebrate and our members have been active in Racing, Cruising & Social activities. We kicked off the summer on July 4th with the christening of our new lawn area and July 4th BBQ. Almost 100 members attended this event and around 20 members continued the celebrations at the South Beach Cruise Out. Thanks go out to all the members who supported our club through the various events and recognition to those who committed their time and energies to organizing. During the Summer, Alameda Police made a visit to our docks. Overall, the visit was positive, though several boats with expired CF numbers were cited. As we look to enhance the security of our facility, we will likely have more visits so please look to make them welcome if you meet the Police, USCG or other agencies on our dock. In relation to USCG, we are also aware that they have been boarding boats in the estuary to check safety equipment and documentation. It’s end of season sale time at many chandlers so now may be a good time to check your equipment! Our September Board meeting has been brought forward to September 5th at 6pm, this to accommodate the delta Cruise Out and various travel commitments. -

Naval Ships' Technical Manual, Chapter 583, Boats and Small Craft

S9086-TX-STM-010/CH-583R3 REVISION THIRD NAVAL SHIPS’ TECHNICAL MANUAL CHAPTER 583 BOATS AND SMALL CRAFT THIS CHAPTER SUPERSEDES CHAPTER 583 DATED 1 DECEMBER 1992 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE, DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED. PUBLISHED BY DIRECTION OF COMMANDER, NAVAL SEA SYSTEMS COMMAND. 24 MAR 1998 TITLE-1 @@FIpgtype@@TITLE@@!FIpgtype@@ S9086-TX-STM-010/CH-583R3 Certification Sheet TITLE-2 S9086-TX-STM-010/CH-583R3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter/Paragraph Page 583 BOATS AND SMALL CRAFT ............................. 583-1 SECTION 1. ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES ............................ 583-1 583-1.1 BOATS AND SMALL CRAFT .............................. 583-1 583-1.1.1 DEFINITION OF A NAVY BOAT. ....................... 583-1 583-1.2 CORRESPONDENCE ................................... 583-1 583-1.2.1 BOAT CORRESPONDENCE. .......................... 583-1 583-1.3 STANDARD ALLOWANCE OF BOATS ........................ 583-1 583-1.3.1 CNO AND PEO CLA (PMS 325) ESTABLISHED BOAT LIST. ....... 583-1 583-1.3.2 CHANGES IN BOAT ALLOWANCE. ..................... 583-1 583-1.3.3 BOATS ASSIGNED TO FLAGS AND COMMANDS. ............ 583-1 583-1.3.4 HOW BOATS ARE OBTAINED. ........................ 583-1 583-1.3.5 EMERGENCY ISSUES. ............................. 583-2 583-1.4 TRANSFER OF BOATS ................................. 583-2 583-1.4.1 PEO CLA (PMS 325) AUTHORITY FOR TRANSFER OF BOATS. .... 583-2 583-1.4.2 TRANSFERRED WITH A FLAG. ....................... 583-2 583-1.4.3 TRANSFERS TO SPECIAL PROJECTS AND TEMPORARY LOANS. 583-2 583-1.4.3.1 Project Funded by Other Activities. ................ 583-5 583-1.4.3.2 Cost Estimates. ............................ 583-5 583-1.4.3.3 Funding Identification. -

Comment on Robert H. Rotstein, Beyond Metaphor: Copyright Infringement and the Fiction of the Work

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 68 Issue 2 Symposium on Intellectual Property Article 10 Law Theory April 1993 Adrift in the Intertext: Authorship and Audience Recoding Rights - Comment on Robert H. Rotstein, Beyond Metaphor: Copyright Infringement and the Fiction of the Work Keith Aoki Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Keith Aoki, Adrift in the Intertext: Authorship and Audience Recoding Rights - Comment on Robert H. Rotstein, Beyond Metaphor: Copyright Infringement and the Fiction of the Work, 68 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 805 (1992). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol68/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ADRIFT IN THE INTERTEXT: AUTHORSHIP AND AUDIENCE "RECODING" RIGHTS-COMMENT ON ROBERT H. ROTSTEIN, "BEYOND METAPHOR: COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT AND THE FICTION OF THE WORK"* KE TH AOKI** I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 805 II. SUMMARY ............................. * ... ...... 806 III. THE AUTHOR is DEAD, BUT WHO SIGNS THE DEATH CERTIFICATE? ............................................. 811 A. Jaszi on Authorship and Copyright ...................... 811 B. Authorship, Moral Rights, and "Tilted Arc" as Textual E vent ................................................. 816 C Authorship, Texts, and Boyle on Spleens ................ 821 IV. EvENTS OF SPEECH AS AUDIENCE "RECODING" RIGHTS ... 825 A. Conservative Opposition ................................ 827 B. Speech Regulation as Two-Edged Sword ................ 831 C. Commodifying the Intertext ............................ -

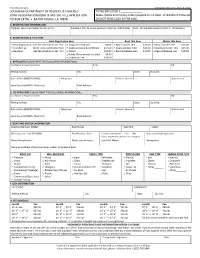

Boat Registration/Boat and Motor Title Application

Revised August 2020 Authorized under LA R.S. 34:851 & 34:852 LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE & FISHERIES TOTAL ENCLOSED $ ______________ BOAT REGISTRATION/BOAT & MOTOR TITLE APPLICATION Make checks and money orders payable to: LA Dept. of Wildlife & Fisheries PO BOX 14796 • BATON ROUGE, LA 70898 DO NOT SEND CASH IN THE MAIL A. REGISTRATION INFORMATION CURRENT LOUISIANA REGISTRATION (LA #): PREVIOUS OUT-OF-STATE REGISTRATION # (IF APPLICABLE): COAST GUARD DOCUMENTATION # (IF APPLICABLE): B. REGISTRATION & TITLE FEES Boat Registration Fees Boat Title Fees Motor Title Fees □ New Registration (see fee schedule in Sec “G”) □ Duplicate Certificate $8.00 □ New Transfer Title $26.00 □ New Transfer Title $26.00 □ Transfer Fee $8.00 (plus registration fee) □ Duplicate Decal & Certificate $13.00 □ Duplicate Boat Title $23.00 □ Duplicate Motor Title $23.00 □ Renewal (see fee schedule in Sec “G”) □ Dealer $53.00 □ Record/Release Lien $10.00 □ Record/Release Lien $10.00 □ Public (Government use only) $0.00 □ Inspection Fee $28.00 C. APPLICANT (PLEASE PRINT THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION): Last Name or Business Name: First: MI: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip Code: Date of Birth (MM/DD/YEAR): Telephone: Driver’s License #: State Issued: Social Security # (FEIN if Business): Email Address: D. CO-APPLICANT (PLEASE PRINT THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION): Last Name or Business Name: First: MI: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip Code: Date of Birth (MM/DD/YEAR): Telephone: Driver’s License #: State Issued: Social Security # (FEIN if Business): Email Address: E. BOAT -

Interviewee: Marvin J. Perrett, USCGR World War II U

U.S. Coast Guard Oral History Program Interviewee: Marvin J. Perrett, USCGR World War II U. S. Coast Guard Veteran Interviewer: Scott Price, Deputy Historian Date of Interview: 18 June 2003 Place: U. S. Coast Guard Headquarters, Washington, D.C. Marvin Perrett joined the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II and served aboard the Coast Guard-manned attack transport USS Bayfield (APA-33) as a coxswain of one of the Bayfield's landing craft. He was a veteran of the invasions of Normandy, Southern France, Iwo Jima and Okinawa and he even survived the "Exercise Tiger" debacle prior to the Normandy invasion. Although each of these events has received extensive coverage, his story, and the story of the thousands of young men who manned the boats that landed troops on enemy beaches, is little- known. It seems that the men who transported the troops to the beach were often been overlooked by historians, writers, and film producers. Yet, as Mr. Perret points out, without them, how would any invasion have happened? 1 Mr. Perrett's oral history is comprehensive. He describes his decision to join the Coast Guard and he then delves into the extensive training he received and how he was picked to be the sailor in charge of a landing craft. He also describes, in detail, this craft he sailed through enemy fire during the invasions he took part in. The boat he commanded was the ubiquitous LCVP, or "Landing Craft, Vehicle / Personnel. It was made primarily of wood by the famous company Higgins Industries in New Orleans. -

How Woman Survived 41 Days Adrift in Pacific Ocean Angela Johnson

How Woman Survived 41 Days Adrift in Pacific Ocean Angela Johnson At 34, Richard was more than a decade older than his young American lover, but with his lapis lazuli eyes, golden hair and "exotic" English accent, he meant everything to her. They had already spent a year and a half together on the Pacific, delivering and mending boats. True, the distance involved in the new mission was vast, yet the pair had few concerns, as Oldham Ashcraft later recalled in a series of moving interviews: "I'd been sailing blue water for four years. Together we had 50,000 miles of ocean-sailing under our belts. We hugged, laughed, made love and relaxed into 20 days of paradise." But disastrous reality was less than two weeks away, in the shape of tropical storm Raymond, which "tore out of the blue", hit hurricane force then held its peak intensity for two catastrophic days. Sharp spotted a monster wave approaching the Hazana and ordered Oldham Ashcraft below deck while he secured himself with a safety harness and tried to keep the vessel afloat. Moments later she heard him scream, "Oh my God!" and her world was thrust into darkness. Tossed like a cork on the raging ocean, the yacht had flipped end over end. It was 27 hours before she regained consciousness to an eerie silence and utter devastation. The cabin was half-filled with water, everything inside it smashed or scattered on the floor. Scrambling onto the deck she looked desperately for Sharp but found only wreckage. The boat was all-but destroyed: masts were broken off and the waterlogged sails floated uselessly in the water. -

Nouveautés - Mai 2019

Nouveautés - mai 2019 Animation adultes Ile aux chiens (L') (Isle of dogs) Fiction / Animation adultes Durée : 102mn Allemagne - Etats-Unis / 2018 Scénario : Wes Anderson Origine : histoire originale de Wes Anderson, De : Wes Anderson Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman et Kunichi Nomura Producteur : Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Scott Rudin Directeur photo : Tristan Oliver Décorateur : Adam Stockhausen, Paul Harrod Compositeur : Alexandre Desplat Langues : Français, Langues originales : Anglais, Japonais Anglais Sous-titres : Français Récompenses : Écran : 16/9 Son : Dolby Digital 5.1 Prix du jury au Festival 2 cinéma de Valenciennes, France, 2018 Ours d'Argent du meilleur réalisateur à la Berlinale, Allemagne, 2018 Support : DVD Résumé : En raison d'une épidémie de grippe canine, le maire de Megasaki ordonne la mise en quarantaine de tous les chiens de la ville, envoyés sur une île qui devient alors l'Ile aux Chiens. Le jeune Atari, 12 ans, vole un avion et se rend sur l'île pour rechercher son fidèle compagnon, Spots. Aidé par une bande de cinq chiens intrépides et attachants, il découvre une conspiration qui menace la ville. Critique presse : « De fait, ce film virtuose d'animation stop-motion (...) reflète l'habituelle maniaquerie ébouriffante du réalisateur, mais s'étoffe tout à la fois d'une poignante épopée picaresque, d'un brûlot politique, et d'un manifeste antispéciste où les chiens se taillent la part du lion. » Libération - La Rédaction « Un conte dont la splendeur et le foisonnement esthétiques n'ont d'égal que la férocité politique. » CinemaTeaser - Aurélien Allin « Par son sujet, « L'île aux chiens » promet d'être un classique de poche - comme une version « bonza? de l'art d'Anderson -, un vertige du cinéma en miniature, patiemment taillé.