Higher Standards, Better Schools For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playing Pitch Strategy Stage C Needs Assessment Report

Adur & Worthing Playing Pitch Strategy Stage C Needs Assessment Report Adur and Worthing Playing Pitch Strategy Stage C: FINAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT REPORT for Adur and Worthing District Council December 2019 1 | P a g e Adur & Worthing Playing Pitch Strategy Stage C Needs Assessment Report CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Context 8 3 Football 24 4 Cricket 80 5 Rugby 101 6 Hockey 114 7 Tennis and Bowls 124 See also Key Findings and Issues – separate document 2 | P a g e Adur & Worthing Playing Pitch Strategy Stage C Needs Assessment Report 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1.1 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) requires local planning authorities to set out policies to help enable communities to access high quality open spaces and opportunities for sport and recreation. These policies need to be based on a thorough understanding of local needs for such facilities and opportunities available for new provision. 1.2 In view of the above, in 2019 Adur & Worthing Councils appointed Ethos Environmental Planning to review a joint study completed in 2014 to provide an up-to-date and robust assessment identifying needs, surpluses and deficits in open space, sport and recreation to support the Local Plans. 1.3 The two councils have separate local plans; this study will assist Worthing Borough in the preparation of a new plan and will support the implementation of the Adur Local Plan which was adopted in 2017. The study will also inform the Council’s asset management process, health and well-being plans and its investments and infrastructure funding process. 1.4 In summary the requirements of the brief are to provide: A comprehensive Open Space Assessment, Indoor/Built Sports Facilities Needs Assessment that represents an update to the existing (2014) assessment. -

Adur & Worthing Local Walking & Cycling Infrastructure Plan (LCWIP)

Adur & Worthing Councils Local Cycling & Walking Infrastructure Plan We received an overwhelming positive response at the consultation. I’m delighted to support this plan to improve our cycling and walking infrastructure across the Borough Dan Humphreys Leader (Worthing Borough Council) 2 Contents It’s clear that our residents Our vision 4 What is the LCWIP 10 and visitors to the District Adur and Worthing 18 would cycle and walk more Worthing Borough 22 Adur District 28 with improved routes. This plan Case studies 34 provides us with a fantastic Liveable cities & towns 36 Low traffic neighbourhood 38 foundation to create the Worthing walking & cycling network map 40 Adur walking & cycling network map 42 network of the future PCT commute data 46 Neil Parkin PCT school data 47 Worthing PCT commute data 48 Leader (Adur District Council) Adur PCT commute data 49 Worthing PCT school data 50 Adur PCT school data 51 Adur & Worthing census commuters by car 52 Glossary of terms 54 All maps © Crown Copyright and database right (2020). Ordnance Survey 100024321 & 100018824 Our Vision We share the ambition to achieve this through: To create a place where walking and Better Safety Better Mobility cycling becomes The Councils share A safe and reliable way to travel for More people cycling and walking - easy, the preferred way of the government’s short journeys normal and enjoyable ambition: Streets where people cycling and More high quality cycling facilities To make cycling and • • moving around Adur walking feel they belong, and are walking the natural More urban areas that are considered safe • and Worthing. -

Annex SCHEMES to BE PROGRESSED IF DEVELOPER FUNDING IS SECURED

Annex SCHEMES TO BE PROGRESSED IF DEVELOPER FUNDING IS SECURED March 2009 Background This document is called “Schemes to be progressed if developer funding is secured” and is also known as the “Blue Book”. In line with latest national guidance (see below), County and District Councils have developed a structured approach to the identification of transport needs related to development proposals. This aims, in particular, to improve the link between meeting the needs of development and the aims of the Local Transport Plan. The County Council’s Works Programme and Forward Programme are produced annually to list the highways and transport schemes to be progressed with the funds available. This year, the Forward Programme has been extended to include schemes that have been identified, in liaison with the Local Planning Authorities, as meeting LTP objectives but that cannot be progressed within available funding. Developer contributions will be sought towards these schemes, where they are seen to meet the needs of development proposals. This extended Forward Programme has been subject to consultation and will be supported by District Councils and used to assist the development control process. The programme will be updated each year and it is intended to engage wider community interests in developing and updating the programme in future years. Planning Context Planning Policy Guidance Note 13 : Transport requires authorities to demonstrate a linkage between land use planning and transport policies and objectives. PPG13 recognises that: • Local Transport Plans have a central role in co-ordinating and improving local transport provision and should relate to measures which form part of the local approach to the integration of planning and transport. -

Capital Programme 2015 – 2021

CAPITAL PROGRAMME 2015/16 - 2020/21 Appendix 1A SUMMARY OF CAPITAL PAYMENTS Service 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 Subsequent Total £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 Adult Social Care and Health 2,904 15,895 12,700 11,500 0 0 0 42,999 Community Wellbeing 1,160 1,000 0 0 0 0 0 2,160 Education and Skills / Children - Start of Life 60,254 48,597 36,197 29,512 7,464 6,887 0 188,911 Finance 10,955 10,351 3,201 3,201 3,201 3,201 0 34,110 Highways and Transport 42,668 31,780 32,230 43,166 37,035 45,567 38,924 271,370 Leader 2,164 4,368 18,535 53,933 30,600 600 0 110,200 Residents' Services 10,436 8,401 6,221 189 630 700 0 26,577 TOTAL PROGRAMME 130,541 120,392 109,084 141,501 78,930 56,955 38,924 676,327 Financing 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 Subsequent Total £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 Ringfenced Government Grant 42,358 30,051 45,438 51,317 35,109 26,529 3,850 234,652 Un-Ringfenced Government Grant 33,565 31,993 30,106 27,097 24,387 22,553 0 169,701 Capital Receipts 8,874 6,900 2,000 1,500 1,250 1,000 0 21,524 Revenue Contributions to Capital Outlay 33,081 12,860 2,615 8,532 532 532 0 58,152 External Contributions including S106 5,671 4,024 2,736 1,692 1,692 1,692 0 17,507 Core Borrowing 6,992 25,617 17,000 17,000 15,960 4,649 12,573 99,791 Additional Borrowing 0 8,947 9,189 34,363 0 0 22,501 75,000 TOTAL PROGRAMME 130,541 120,392 109,084 141,501 78,930 56,955 38,924 676,327 Income Generating Initiatives 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 Subsequent Total £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 Finance 3,594 7,352 2,506 627 0 0 0 14,079 Leader 20,100 9,500 8,800 6,300 6,300 6,300 25,200 82,500 TOTAL PROGRAMME 23,694 16,852 11,306 6,927 6,300 6,300 25,200 96,579 Agenda Item No. -

Cutting Edge Developments in International CDP

Cutting Edge Developments in International CDP Steve Corcoran, Helena Kang International Short Programme Unit University of Chichester Our programme Part of 3 + 3 Model 3 Months Domestic training 3 Months training abroad Extended School Practicum Programme for In-service Korean English Teachers English education policy in Korea NEAT Emphasis on TEE Content-based Instruction Domestic Training - Insufficient School Practicum Arrangements Schools in and around East and West Sussex 11 Schools: Ø Westergate Community School Ø Park Community School Ø Davison CE High School Ø Midhurst Rother College Ø Rydon Community College Ø The Academy, Selsey Ø Seaford College Ø Bishop Luffa CE School Ø Bourne Community College Ø Angmering School Ø Worthing High School School Practicum Arrangements Extended School placement Opportunity to work alongside different teachers in various subjects and/or observe some lessons KTs to function as Classroom Assistants working at the direction of the teachers/school KTs to teach some lessons to small groups, part or whole classes during placement Take an active part in any extra-curricular activities Teach sessions about their own culture or the Korean language University link tutor/mentor Experience of the KTs to date Observation of lessons Staff meetings Form tutorials Assemblies Assisting lessons Subject teaching Field trips and other extra curricular activities Practicum reflections by the KTs ‘Daily record of experience’ Description Teaching and learning methods Similarities and differences What could be adapted for the Korean classroom? Early findings implementing this programme Cultural issues School distance/Transport Difference in perception of roles in School Critical role of Mentor Preparation for this programme . -

Secondary School Page 0

APPLY ONLINE for September 2021 at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions by 31 October 2020 Admission to Secondary School Page 0 APPLY ONLINE for September 2021 at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions by 31 October 2020 Information for Parents Admission to Secondary School – September 2021 How to apply for a school place – Important action required Foreword by the Director of Education and Skills Applying for a place at secondary school is an exciting and important time for children and their parents. The time has now come for you to take that important step and apply for your child’s secondary school place for September 2021. To make the process as easy as possible, West Sussex County Council encourages you to apply using the online application system at www.westsussex.gov.uk/admissions. All the information you need to help you through the process of applying for a secondary school place is in this booklet. Before completing your application, please take the time to read this important information. The frequently asked questions pages and the admission arrangements for schools may help you decide on the best secondary schools for your child. We recognise that this year has been an unusual year with schools taking additional precautions to ensure safety for both staff and pupils during the current pandemic. However, many schools are making arrangements for prospective parents to better understand the school and to determine whether the school is the right fit for your child. Arrangements for visiting schools or for finding more out about the school may be organised differently to the way schools have managed this previously. -

Category School Name Cost Nursery Bognor Regis £8,197.20 Boundstone £7,120.80 Chichester £8,776.80 Horsham £7,783.20 Primary Albourne C.E

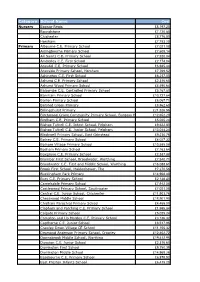

Category School Name Cost Nursery Bognor Regis £8,197.20 Boundstone £7,120.80 Chichester £8,776.80 Horsham £7,783.20 Primary Albourne C.E. Primary School £7,021.08 Aldingbourne Primary School £7,609.14 All Saints C.E. Primary School £7,520.04 Amberley C.E. First School £2,174.04 Arundel C.E. Primary School £6,985.44 Arunside Primary School, Horsham £7,769.52 Ashington C.E. First School £6,237.00 Ashurst C.E. Primary School £2,316.60 Ashurst Wood Primary School £4,490.64 Balcombe C.E. Controlled Primary School £5,167.80 Barnham Primary School £10,727.64 Barton Primary School £6,067.71 Bersted Green Primary £8,862.60 Billingshurst Primary £21,526.56 Birchwood Grove Community Primary School, Burgess Hill £12,652.20 Birdham C.E. Primary School £5,025.24 Bishop Tufnell C.E. Infant School, Felpham £9,622.80 Bishop Tufnell C.E. Junior School, Felpham £13,044.24 Blackwell Primary School, East Grinstead £9,230.76 Bolney C.E. Primary School £4,027.32 Bolnore Village Primary School £10,585.08 Bosham Primary School £7,163.64 Boxgrove C.E. Primary School £2,387.88 Bramber First School, Broadwater, Worthing £7,540.71 Broadwater C.E. First and Middle School, Worthing £16,088.61 Brook First School, Maidenbower, The £7,270.56 Buckingham Park Primary £14,968.80 Bury C.E. Primary School £2,138.40 Camelsdale Primary School £7,912.08 Castlewood Primary School, Southwater £7,021.08 Central C.E. Junior School, Chichester £11,903.76 Chesswood Middle School £18,901.90 Chidham Parochial Primary School £4,455.00 Clapham and Patching C.E. -

2016 Children with EHCP Or Statement of SEN (Under Age Of

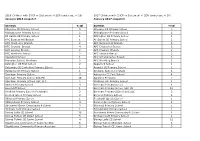

2016 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) 2017 Children with EHCP or Statement of SEN (under age of 16) January 2016 snapshot January 2017 snapshot SCHOOL Total SCHOOL Total Albourne CE Primary School 5 Albourne CE Primary School 3 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 Aldingbourne Primary School 2 All Saints CE Primary School 1 Aldrington CE Primary School 1 APC Burgess Hill Branch 1 All Saints CE Primary School 2 APC Chichester Branch 2 APC Burgess Hill Branch 5 APC Crawley Branch 4 APC Chichester Branch 3 APC Lancing Branch, 2 APC Crawley Branch 1 APC Worthing Branch 2 APC Lancing Branch 3 Appleford School 1 APC Littlehampton Branch 1 Arunside School, Horsham 3 APC Worthing Branch 1 Ashington CE First School 2 Appleford School 1 Balcombe CE Controlled Primary School 1 Arundel CE Primary School 1 Baldwins Hill Primary School 1 Arunside School, Horsham 4 Barnham Primary School 3 Ashington CE First School 4 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Awaiting Provision 7 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 2 Baldwins Hill Primary School 4 Bartons Primary School 4 Barnham Primary School 4 Beechcliff School 1 Barnham Primary School SSC PD 10 Benfield Primary School (Portslade) 2 Barnham Primary SChool SSC SLC 3 Bersted Green Primary School 2 Bartons Primary School 4 Bilingual Primary School 1 Beechcliff Special School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 4 Bersted Green Primary School 3 Birchwood Grove Community P School 3 Bilingual Primary School 1 Birdham CofE Primary School 1 Billingshurst Primary School 2 Bishop Luffa CE School 10 Birchwood Grove -

Choosing Your New School With

A Pull Out Choosing your and Keep New School Feature Kids travel with The definitive guide for just to open days for that all important decision. If you have an adult ticket you can buy our ‘kid for a quid’ £1 add-on ticket. This allows you to travel with one child, for one day, for £1. You can buy up to a maximum of four tickets, that’s just £4 for four kids. Now available to buy with concession passes Buy it on the bus, pay cash or contactless Find out more at stagecoachbus.com/kidforaquid Choosing your New School Starting to look at secondary schools? We Make a Shortlist of Schools give you the lowdown on what to do. Firstly, make a shortlist of the schools that your child could attend by looking at nearby local authority’s websites or visit Choosing a secondary school is one of the most www.education.gov.uk. Make sure you check their admission important decisions you are going to make because rules carefully to ensure your child is eligible for a place. You it’s likely to have a huge impact on your child’s also need to be happy that your child can travel to school future, way beyond the school gates. There’s some easily and that siblings, if relevant, could go to the same essential ‘homework’ to be done before you make school. After that, it’s time to take a look at the facts and Choosing your new School that all important choice and you must make sure figures to make a comparison on paper. -

Appendix, Chichester Festival Theatre Outreach

Appendix Chichester Festival Theatre Outreach activity across West Sussex 1. Examples of Partnership Activity • Specialist School Arts Festival/Light On Its Feet – developed with the support of Bognor Regis Community College, Bourne Community College, Chatsmore Catholic High School, Chichester High School for Boys, Chichester High School for Girls, Oak Grove College, Oakmeeds Community College, Oathall Community College, Oriel High School, The Littlehampton Academy, The Sir Robert Woodard Academy, Westergate Community School a festival which will provide affordable, technically ambitious, access to the Minerva in March 2011 • Partnership with West Sussex County Music for two performances in February 2011 of “A Celebration of Young Musicians”, hosting 100s of young musicians from across county’s groups in the Festival Theatre • Blue Touch Paper Carnival – CFT host meetings and conferences for this Ahead of the Game project to create and inspire accessible carnival as part of the local 2012 Olympics and Paralympic celebrations • Dialog Project – CFT gives support in kind, space and hosts the Dialog project (West Sussex Arts Partnership supported), to provide a for cultural exchanges between schools (eg. Angmering, Bishop Luffa, Bognor Regis, and Durrington High School), artists from around the world and the general public • Projects commissioned by West Sussex Action Against Bullying project involving schools from Worthing, Midhurst, Shoreham, Horsham, Burgess Hill and East Grinstead • Scene It – CFT developed, promoted and ran open workshops -

Schools Forum Membership

EDUCATION AND SKILLS (Schools) FORUM MEMBERSHIP: SCHOOLS MEMBERS Primary School Representatives (10) Headteachers (7): Debbie Carter Horsham Nursery School, Horsham Gill Leadbetter-Simms St Mary’s CofE First School, Washington Sian Rees-Jones Bognor Regis Nursery School, Bognor Regis Chris Luckin Steyning Primary School, Steyning Richard Yelland St John the Baptist CofE Primary, Worthing Dean Clegg Thorney Island CP School, Emsworth Shelley Dutson St Mary’s CofE, Horsham Substitutes: Becky Linford Upper Beeding Primary, Steyning Governors (3) David Herson Steyning Primary School, Steyning Howard Oyns Milton Mount Primary School, Crawley VACANCY Secondary School Representatives (5) Headteachers (3) Peter Woodman The Weald School, Billingshurst Simon Liley Bourne Community College, Emsworth Eddie Rodriguez Oathall Community College, H Heath Substitute: David Brixey The Angmering School, Littlehampton Governors (2): Ken Lloyd Felpham Community College, Bognor Regis John Thompson Davison High School, Worthing Substitute Stewart Boyling Oathall Community College, H Heath Special School representatives (2) Headteacher (1): Grahame Robson Manor Green College, Crawley Substitute: Maria Davis Cornfield School, Littlehampton Governor (1): Therese Brook Fordwater School, Chichester Substitute Matthew Young Herons Dale School, Shoreham By Sea ACADEMIES MEMBERS Academies Representatives (7) Secondary (4) Colin Granlund (BM) Warden Park Academy Trust Carolyn Dickinson (HT) Worthing High School, Worthing Mike Garlick (Principal) The Regis School, Bognor -

WSCC TTS 6Pp Newsletter

ROAD RACE - UP year, the performances will be shown to to examine what life would be like in the upper year students at primary schools. future unless we adopt the ‘TravelWise’ AND COMING message. And then we ask them to look SPEED COMMITMENT at what measures they can adopt in their The “Make the Commitment” campaign communities by reducing danger The StopWatch Theatre Company own lives to make a difference in is part of a long-term strategy in Sussex and nuisance to other road users reducing the reliance on cars. This work to create a safer environment for road •Make speeding as socially The performance, which combines compliments School Travel Plan users, especially pedestrians and cyclists. unacceptable as drink driving has theatre in education and a drama development, which is now widely being 25 sites have been now been introduced become. • Storrington Primary workshop will run for 2 week (w/b 7 undertaken across West Sussex. across the county and you will probably •Portfield Community Primary October and w/b/21 October). “Road be aware of the ‘Kill Your Speed’ signs. Over the last year, 10 schools have been (Chichester) Race” is part of the County Council’s Changing attitudes of road users is an The main objectives of the campaign involved in the Speed Commitment • Balcombe Primary TravelWise initiative which encourages important part of TravelWise and raising include; Campaign within their local area. School • Handcross Primary & drivers to use their cars more responsi- awareness of children of the alternatives • Encouraging drivers to make a participation has included designing Handcross School bly and encourages the use of the alter- to car travel will help to educate them personal commitment to keep posters and publicity material.