Midl` Mlva in GOD’S IMAGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yom Kippur Additional Service

v¨J¨s£j jUr© rIz§j©n MACHZOR RUACH CHADASHAH Services for the Days of Awe ohrUP¦ ¦ F©v oIh§k ;¨xUn YOM KIPPUR ADDITIONAL SERVICE London 2003 - 5763 /o¤f§C§r¦e§C i¥T¤t v¨J¨s£j jU© r§ «u Js¨ ¨j c¥k o¤f¨k h¦T©,¨b§u ‘I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you.’ (Ezekiel 36:26) This large print publication is extracted from Machzor Ruach Chadashah EDITORS Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein Rabbi Dr Charles H Middleburgh Editorial Consultants Professor Eric L Friedland Rabbi John Rayner Technical Editor Ann Kirk Origination Student Rabbi Paul Freedman assisted by Louise Freedman ©Union of Liberal & Progressive Synagogues, 2003 The Montagu Centre, 21 Maple Street, London W1T 4BE Printed by JJ Copyprint, London Yom Kippur Additional Service A REFLECTION BEFORE THE ADDITIONAL SERVICE Our ancestors acclaimed the God Whose handiwork they read In the mysterious heavens above, And in the varied scene of earth below, In the orderly march of days and nights, Of seasons and years, And in the chequered fate of humankind. Night reveals the limitless caverns of space, Hidden by the light of day, And unfolds horizonless vistas Far beyond imagination's ken. The mind is staggered, Yet soon regains its poise, And peering through the boundless dark, Orients itself anew by the light of distant suns Shrunk to glittering sparks. The soul is faint, yet soon revives, And learns to spell once more the name of God Across the newly-visioned firmament. Lift your eyes, look up; who made these stars? God is the oneness That spans the fathomless deeps of space And the measureless eons of time, Binding them together in deed, as we do in thought. -

Who Shall I Say Is Calling? Unetaneh Tokef As a Call to Change Our Lives for the Better.1 Rabbi Jordan M

Who Shall I Say is Calling? Unetaneh Tokef as a call to change our lives for the better.1 Rabbi Jordan M. Ottenstein, RJE Beth-El Congregation, Fort Worth, Texas Rosh Hashanah Morning, 5776 A story is told of Rav Amnon of Mainz, a rabbi of the Middle Ages, who “was the greatest of his generation, wealthy, of fine lineage, well built, and handsome. The nobles and bishop began asking him to apostacize,”2 to convert to Christianity, but he refused to listen. Yet, after continually pestering him with the same question, Rav Amnon told the bishop, “I want to seek advice and think the matter over for three days.”3 But, the minute he left the presence of the bishop after saying these words, he began to feel guilty. He was unable to eat or drink, the guilt he had over even saying that there was possibility he might leave Judaism was so great. And so, on the third day, he refused to go to the bishop when summoned. The bishop then sent his guards to bring Amnon before him against his will. “He asked, ‘What’s this Amnon, why didn’t you come back as stipulated— that you would take counsel and get back to me and do what I asked?’” Amnon replied, ‘Let me adjudicate my own case. The tongue that lied to you should be sentenced and cut off.’ ‘No,’ the bishop responded.’ It is not your tongue that I will cut off, for it spoke well. Rather it is your legs that did not come to me, as you promised, that I will chop off, and the rest of your body I will torment.’”4 After being tormented and tortured, Amnon was returned to his community on Rosh Hashanah. -

Unetaneh Tokef by JENNIFER RICHLER Feelings

the Jewish bserver www.jewishobservernashville.org Vol. 80 No. 9 • September 2015 17 Elul 5775-17 Tishrei 5776 New Year Shana Tova 5776 Greetings, page 12 2016 annual campaign begins; aims to raise $2.5 million to sustain Jewish communities here and around the globe By CHARLES BERNSEN here were plenty of stalwart veterans among the volun- teers who gathered last month for the launch of the Jewish Federation of the meeting room of the Gordon Jewish Nashville and Middle Community Center for an initial hour- TTennessee’s 2016 annual campaign. But long workshop. there also were some eager young rookies. This marks the fourth year in which Andrea and Kevin Falik, both 29, are campaign volunteers have been divided co-captains of a team of volunteers who into teams for a friendly competition will focus on engaging young adults in the called the Kehillah Cup Challenge. For annual campaign, which is seeking to the 2016 campaign there are eight teams, raise $2.5 million that will be distributed each with a captain and between five and to 77 institutions and programs in eleven members who have been assigned Nashville, Israel and Jewish communities to solicit up to half a dozen members of around the world. Andrea and Kevin Falik (on right) are co-captains of a team that will focus on engaging young the Bonim Society, whose previous annu- “Andrea and I look at this as an adults in the 2016 annual campaign of the Jewish Federation of Nashville and Middle Tennessee. Here they are talking with Batia and Aron Karabel, co-chairs of the philanthropic arm of al gifts range from $1,000 to $100,000. -

A Talmudic Reading of the High Holiday Prayer Untaneh Tokef

Zeramim: An Online Journal of Applied Jewish Thought Vol. II: Issue 3 | Spring 2018 / 5778 A TALMUDIC READING OF THE HIGH HOLIDAY PRAYER UN’TANEH TOKEF Judith Hauptman Jews flood the synagogues on Rosh Hashanah. Many who do not show up at any other time find their way to services on the very day that the liturgy is the longest. True, they come to hear the shofar blown, but they also come to hear, at the beginning of the repetition prayer. What makes this 1( נוהנת קת ף ) of Musaf, the Un’taneh Tokef prayer so attractive? Could it be the poignant question, “Who will live and who will die?” Or the daunting list of ways in which one may die? Most people think that the message of this piyyut, or liturgical poem, is that our fate is in God’s hands, that it is God who determines how long we live, and that we have, at best, little control over our fu- ture. These ideas are borne out, or perhaps suggested, by many of the English translations of the climactic line of this prayer, ut’shuvah, הבותוש הלתופ הצוקד ) ut’filah, uz’dakah ma’avirin et ro’a hagezeirah :Here are a few 2.( בעמ י ר י ן תא ער גה ז י הריזג Gates of Repentance (Reform, 1978): “But repentance, prayer, and charity temper judgment’s severe decree.”3 netaneh) the power , התננ ) These words mean, “We will acknowledge 1 -tokef) [of this day’s holiness].” This prayer is a well-known fea , ףקות ) ture of the Ashkenazi rite. -

Rosh Hashanah Shana Tova!

September 4-10, 2021 • Elul 27, 5781 - Tishrei 4, 5782 T This Week at YICC Rosh HaShanah Shana Tova! ROSH HASHANAH SCHEDULE PRAY FOR SHALOM IN MEDINAT YISRAEL! Erev Rosh Hashanah, Monday Sept 6 Candles ................................................ 5:53-6:54 PM PLEASE BE SURE TO BRING ID WITH YOU Shkiah ........................................................... 7:12 PM Mincha .......................................................... 7:00 PM TO SHUL TO EXPEDITE ENTRY. First Day Rosh HaShanah, Tuesday, September 7 Shacharit at all Minyanim ............................. 8:00 AM Tashlich Mincha .......................................................... 6:45 PM MASKS ARE MANDATORY IN SHUL Shiur by Rabbi Dr. Zev Wiener Maariv and Candles ............................. after 7:56 PM Due to the serious increase in people being infected with Covid-19, the LA County Dept of Health Second Day Rosh HaShanah, Wed, September 8 requires masks be worn in indoor public spaces Shacharit at all Minyanim ............................. 8:00 AM regardless of one’s vaccination status. Mincha .......................................................... 6:45 PM Shiur by Rabbi David Mahler Therefore, our Shul has resumed the requirement that Maariv ........................................................... 7:44 PM everyone inside the Shul building wear a mask, Yom Tov ends and Havdalah ....................... 7:54 PM and do so CORRECTLY – whereby the mask Selichot at Anziska’s .................................... 9:00 PM covers both one’s mouth and nose. Thank -

The Conversaĕon Yom Kippur Sermon by Rabbi Esther Adler Mount Zion Temple, Saint Paul, MN 5777 / 2017

The Conversaĕon Yom Kippur Sermon by Rabbi Esther Adler Mount Zion Temple, Saint Paul, MN 5777 / 2017 Before beginning college last month, University of Chicago freshmen received a welcome leĥer from the dean with a warning that the school does not support “trigger warnings.” I had never heard of this, but apparently trigger warnings have become fodder for folks on both the right and the le├ who believe they have goĥen totally out of hand. For those of you who, like me, are a liĥle behind on popular culture, these are statements at the beginning of a course, reading, or media presentaĕon, that the content that might offend or “trigger” a traumaĕc response in the consumer. The university of Chicago said no more Trigger warnings, so students, be prepared...We are not at the University of Chicago, so I am going to go ahead and issue a “trigger warning:” This sermon might be hard to hear. I hope it will be a trigger ‐ not for a traumatic response , but for a thoughĔul one. I am going to talk about something nobody wants to talk about, but that needs to be talked about. Have you had “the talk?” No, not that talk. That talk is easy compared to this talk. Bear with me. I’m going to ease us into this. In her 2012 book “I hate everyone...starĕng with me” Joan Rivers wrote: When I die (and yes, Melissa, that day will come; and yes, Melissa, everything’s in your name), I want my funeral to be a huge showbiz affair with lights, cameras, action . -

UNETANNEH TOKEF. on Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur We

UNETANNEH TOKEF. On Rosh Hashanah and on Yom Kippur we read, or sing, a poem of great power. The “Unetanneh Tokef” has some traditional melodies associated with it, and forms a lengthy Piyut with sections sung as a form of refrain or counter-point. There are various traditions about this piece and its origins. Some relate to Rabbi Amnon of Mayence who related it in a dream after he had been martyred, tortured to death shortly before Rosh Hashanah for refusing to convert to Christianity. This legend is picturesque, painful, but nothing more than that - a legend. So much of the liturgy we use is anonymous, its origins lost in history. Occasionally a piece has a known author, occasionally an author has put at least his first name into some form of clever acrostic pattern, but this is the exception, not the rule; On the whole, we pray the words of anonymous poets, compiled - and, for all we know, revised - over many centuries. And these words have their power not because the author is famous, but because the author managed to write what we often feel. Even if the language or the style has become antiquated, the message can retain its power. So I do not wish to give here a history lesson, but instead look at the text. It can be found on both these days at the beginning of the Mussaf service, incorporated somehow into the “Keduscha” of the Amidah. (Seder Hatefillot, Band II, pp. 246-249, 478-491.) The word “Tokef” means something overpowering. It is used as such only three times in the Tanach - once in Daniel 11:17, referring to “the power of the whole kingdom”, and then in Esther 9:29 and 10:2, again with reference to a king’s rule and power. -

The Stories Behind High Holiday Prayers Week 1: Unetaneh Tokef Ezer Diena, [email protected]

Did It Really Happen? The Stories Behind High Holiday Prayers Week 1: Unetaneh Tokef Ezer Diena, [email protected] 1. Who By Fire, Who By Water – Un’taneh Tokef, edited by Lawrence Hoffman (https://bit.ly/2kRNRBN) 2. Nissan Mindel, Rabbi Amnon of Mayence, The Gallery of our Great, Chabad.org (https://bit.ly/2koP2II) More than eight hundred years ago there lived a great man in the city of Mayence (Maintz). His name was Rabbi Amnon. A great scholar and a very pious man, Rabbi Amnon was loved and respected by Jews and non-Jews alike, and his name was known far and wide. Even the Duke of Hessen, the ruler of the land, admired and respected Rabbi Amnon for his wisdom, learning, and piety. Many a time the Duke invited the Rabbi to his palace and consulted him on matters of State. Rabbi Amnon never accepted any reward for his services to the Duke or to the State. From time to time, however, Rabbi Amnon would ask the Duke to ease the position of the Jews in his land, to abolish some of the decrees and restrictions which existed against the Jews at the time, and generally to enable them to live in peace and security. This was the only favor that Rabbi Amnon ever requested from the Duke, and the Duke never turned down his request. Thus, Rabbi Amnon and his brethren lived peacefully for many years. Now the other statesmen of the Duke grew envious of Rabbi Amnon. Most envious of them all was the Duke's secretary, who could not bear to see the honor and respect which Rabbi Amnon enjoyed with his master, which was rapidly developing into a great friendship between the Duke and the Rabbi. -

Hartmansummer@Home Themes of the High Holidays Hayom Harat Olam: One Small Liturgical Text, One Giant Trove of Interpretation

HartmanSummer@Home Themes of the High Holidays Hayom Harat Olam: One Small Liturgical Text, One Giant Trove of Interpretation Gordon Tucker July 13 and 15, 2020 1. Hayom Harat Olam, Piyut (Liturgical Poem) for Rosh Hashanah Musaf 1 2. Max Arzt, Justice and Mercy, 1963, pg. 168 2 3. Jeremiah 20:7-18 3 4. Norman Lamm, from a sermon on the 2nd Day of Rosh Hashanah 5724 (September 20, 1963) 5 5. Gerson D. Cohen, The Soteriology of R. Abraham Maimuni, 1967, reprinted in Studies in the Variety of Rabbinic Cultures, pp. 223–4 6 6. Sarah Friedland ben Arza, “Harat Olam - On the Birth of the World on Rosh Hashanah” 7 The Shalom Hartman Institute is a leading center of Jewish thought and education, serving Israel and North America. Our mission is to strengthen Jewish peoplehood, identity, and pluralism; to enhance the Jewish and democratic character of Israel; and to ensure that Judaism is a compelling force for good in the 21st century. Share what you’re learning this summer! #hartmansummer @SHI_america shalomhartmaninstitute hartmaninstitute 475 Riverside Dr., Suite 1450 New York, NY 10115 212-268-0300 [email protected] | shalomhartman.org 1. Hayom Harat Olam, Piyut (Liturgical Poem) for Rosh Hashanah Musaf, subsequent to the blowing of the Shofar הַ יּוֹם הֲרַ ת עוֹלָם. הַ יּ וֹ ם ַי ֲע מִ י ד בַּ מִּ שְׁ ָ פּ ט. כָּ ל יְ צוּרֵ י עוֹלָמִ ים. אִ ם כְּבָנִים. אִ ם כַּעֲבָדִ ים. אִ ם כְּ בָ נִ י ם. רַ חֲ מֵ ֽ נוּ כְּ רַ חֵ ם אָ ב עַ ל בָּ נִ ים. -

Yom Kippur Kol Nidre

Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die: Perspectives of Unetaneh Tokef Kol Nidre 5776 / September 22, 2015 On September 11, 2001, I was a fourth-year cantorial student, living on Long Island, New York, attending Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion. It was a Tuesday morning. I came out of the subway with my beloved teacher, Joyce Rozensweig, with whom I had a 9:00 class, as well as a couple other students. Unusual, really. I never saw anyone I knew on the subway. Snaking across Broadway was a curious trail of pale gray smoke. It struck me as odd… Upon entering the lobby of the College-Institute, the news came. A plane had struck the World Trade Center. Standing on the corner of West Fourth and Mercer Streets we saw the gaping hole from which bellowed flames of orange and thick, black smoke. You know the rest of what happened that day. Those events will forever be seared upon our minds and hearts. Unlike many other congregations, my student pulpit, Temple Emanuel of New Hyde Park, was quite fortunate. We had only one congregant who worked in the Towers, and he just happened to stop for coffee that day, never making it into the building before tragedy struck. The next evening my congregation held a memorial service for the souls that had been lost. I created new words for the memorial prayer, El Malei Rachamim. Rosh Hashanah began just five evenings later. My most vivid memory of the High Holy Days that year was the chanting of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer that Rosh Hashanah morning. -

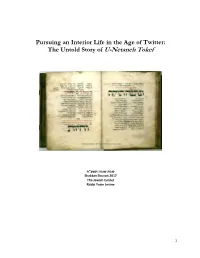

The Untold Story of U-Netaneh Tokef

Pursuing an Interior Life in the Age of Twitter: The Untold Story of U-Netaneh Tokef שבת שובה תשע"ח Shabbat Shuvah 2017 The Jewish Center Rabbi Yosie Levine 1 A few months ago, I visited my doctor for my annual physical. In the waiting room there was one other person - a Chassidish gentleman with a hat and a beard - wearing a bekishe. A few moments later when I was in the exam room, I heard the doctor say to the nurse: "Can you do me a favor and grab the rabbi's chart?" She said, "Which rabbi?" To which the doctor said: "The religious one; not the modern religious one." So this morning I'd like to try to find a modern religious solution to a medieval problem.... No talk about U-Netaneh Tokef can begin without mention of the legend surrounding its composition. Virtually everything we know about the Tefillah comes to us from the Or Zarua. 1 אור זרוע ח"ב הלכות ראש השנה ס ' רע"ו A Brief Summary of the מצאתי מכתב ידו של ה"ר אפרים מבונא בר יעקב . שר ' אמנון ממגנצא יסד ונתנה Legend תוקף על מקרה הרע שאירע לו וז"ל : מעשה בר ' אמנון ממגנצא שהיה גדול הדור A certain Rabbi Amnon of ועשיר ומיוחס ויפה תואר ויפה מראה והחלו השרים וההגמון לבקש ממנו שיהפך Mainz was pressured by the לדתם וימאן לשמוע להם ויהי כדברם אליו יום יום ולא שמע להם ויפצר בו ההגמון local bishop to convert ויהי כהיום בהחזיקם עליו ויאמר חפץ אני להועץ ולחשוב על הדבר עד שלשה ימים to Catholicism. -

Unetane Tokef

Let us proclaim the sacred power of this day: it is awesome and full of dread For on this day Your dominion is exalted, Your throne established in steadfast love; there in truth You reign. In truth You are Judge and Arbiter, counsel and Witness. You write and You seal, You record and recount. You open the book of our days, and what is written there proclaims itself, for it bears the signature of every human being. The great Shofar is sounded, the still, small voice is heard; the angels, gripped by fear and trembling, declare in awe: This is the Day of Judgement! For event he hosts of heaven are judged, as all who dwell on earth stand arrayed before You. As the shepherd seeks out his flock, and makes the sheep pass under his staff, so do You muster and number and consider every soul, setting the bounds of every creature’s life, and decreeing its destiny. On Rosh Hashanah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed: How many shall pass on, how many shall come to be; who shall live and who shall die; who shall see ripe age and who shall not; who shall perish by fire and who by water; who by sword and who by beast; who by hunger and who by thirst; who by earthquake and who by plague; who by strangling and who by stoning; who shall be secure and who shall be driven; who shall be tranquil and who shall be troubled; who shall be poor and who shall be rich; who shall be humbled and who exalted.