Employment and Changing Occupational Patterns in the Railroad Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WP Mileposts Summer Fall 1976 No

WESTERN PACIFIC The Bicentennial Year MilepoSts SUMMER-FALL 1976 The Intermodal group also works closely with D. L. Loftus, Director In termodal Development (contracts, equipment, profit analysis), D. C. Pendleton, Manager Intermodal Pric ing (tariff changes) as weI! as WP's Operating Department (schedules and The "piggy-packer" with arms train operations), and Western Pa extend d ca n unload vans (or cific Transport Company (terminal trail r ) with the same ease it can I'wist a container from or loading, unloading and pick-up and to the railroad flat cars_ These delivery) . cars are designed to handle bOUl vans and containers for The Intermodal Sales Team coor the railroad. dinates and assists the WP sales offices across the country in making customer contacts, securing new profitable busi ness, and offering expertise in intel' modal sales and service. The Team's With the aid of the WP 'morning report· Miss eoverage includes a wide range of in Rita Connelly, Manager-Intermodal Service ad vises customers the latest schedules for ar termodal customers, such as: freight rival and delivery of their vans or containers. forwarders, shippers agents, shipping Rita is headquartered in the San Francisco associations, steamship lines, steam office. ship agencies, container companies, w.P. Establishes Intermodal Dept. brokers, local truck lines, trading companies and individual shippers_ The 'Team' maintains close associa t ion with the large northern Califor nia ports. Included on this list are the P orts of Oakland, San Francisco, The development and growth of sales team of experienced personnel Stockton and Sacramento. containers and trailers on flatcars, trained to handle the specialized needs Intermodal (container and trailer) commonly known in the industry as of the Intermodal customer. -

CONTRACT T-8000-1415 AUTOMATIC TRAIN CONTROL TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents

ATTACHMENT C PART 2 – ATC SYSTEM MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION CONTRACT T-8000-1415 AUTOMATIC TRAIN CONTROL TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents 1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS 2 COMMUNICATIONS BASED TRAIN CONTROL REQUIREMENTS 3 MAIN LINE AND STORAGE YARD SOLID STATE INTERLOCKING REQUIREMENTS 4 AUTOMATIC TRAIN SUPERVISION REQUIREMENTS 5 DATA COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS 6 AUXILIARY WAYSIDE EQUIPMENT REQUIREMENTS 7 ENVIRONMENTAL AND EMC 8 SYSTEM SAFETY REQUIREMENTS 9 RELIABILITY, AVAILABILITY, AND MAINTAINABILITY REQUIREMENTS 10 INSTALLATION CUTOVER AND CONSTRUCTION REQUIREMENTS 11 ATC TESTING 12 QUALITY ASSURANCE AND CONTROL 13 TECHNICAL SUPPORT 14 TRAINING Attachment C, Part 2, ATC System T-8000-1415 i September 2015 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Attachment C, Part 2, ATC System T-8000-1415 ii September 2015 SECTION 1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS Contents 1.1 GENERAL..................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ...............................................................................................................1-2 1.2.1 PROVEN DESIGN......................................................................................................1-3 1.2.2 COMMISSIONING ON A REVENUE SYSTEM...............................................................1-3 1.2.3 DESIGN LIFE.............................................................................................................1-3 1.3 SCOPE OF WORK......................................................................................................................1-3 -

Rail Train Operating Instructions

Union Pacific Railroad Rail Train Operating Instructions REVISED: March 8, 2010 1 Table of Contents Section Page No. Introduction 3 Job Briefing 5 Manpower 8 Communication 9 Train and Equipment Consist 10 Rail Unloading Operation s 11 Rail Pick-Up Operations 15 2 Rail Train Operating Instructions Introduction Rail replacement is an important part of Union Pacific’s track maintenance program. Each year, new Continuous Welded Rail (CWR) is unloaded system wide for installation. Likewise, secondhand CWR and bolted rail is picked-up by Rail Trains, and is either transported to system rail plants, or cascaded to other secondhand curve rail projects. System trains used in this process consist of two rail unloading cars, and four to five rail car pick-up units for secondhand rail. Compliance with these instructions will ensure the safe and efficient operation of all Rail Train operations. The Manager Track Maintenance (MTM) or appointed supervisor will assist the Rail Train Supervisor (RTS) during all Rail Train operations. Local management is responsible for: 1) Reviewing project plans before the Rail Train's arrival to ensure the efficient unloading of rail. 2) Obtaining and communicating the proper exclusive track occupancy (Form B, Form C, single-tracking and flag protection) to all interested parties as required. Coordinate moves with Maintenance-of-Way Operations Control (MWOC), Corridor Manager, and other Maintenance-of-Way gangs working in the area. 3) Providing the Rail Train Supervisor with a copy of General Orders and information about the territory that may affect the operation (i.e., location of bridges, signals, switches and other obstructions). -

49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–11 Edition)

§ 224.1 49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–11 Edition) 224.9 Responsibility for compliance. and prescribes standards for the appli- 224.11 Penalties. cation, inspection, and maintenance of 224.13 Preemptive effect. retroreflective material to rail freight 224.15 Special approval procedures. rolling stock for the purpose of enhanc- Subpart B—Application, Inspection, and ing its detectability at highway-rail Maintenance of Retroreflective Material grade crossings. This part does not re- strict a freight rolling stock owner or 224.101 General requirements. railroad from applying retroreflective 224.103 Characteristics of retroreflective material to freight rolling stock for sheeting. other purposes if not inconsistent with 224.105 Sheeting dimensions and quantity. 224.106 Location of retroreflective sheeting. the recognizable pattern required by 224.107 Implementation schedule. this part. 224.109 Inspection, repair, and replacement. 224.111 Renewal. § 224.3 Applicability. APPENDIX A TO PART 224—SCHEDULE OF CIVIL This part applies to all railroad PENALTIES freight cars and locomotives that oper- APPENDIX B TO PART 224—FORM ate over a public or private highway- REFLECTORIZATION IMPLEMENTATION COM- rail grade crossing and are used for rev- PLIANCE REPORT APPENDIX C TO PART 224—GUIDELINES FOR enue or work train service, except: SUBMITTING REFLECTORIZATION IMPLE- (a) Freight rolling stock that oper- MENTATION COMPLIANCE REPORTS ates only on track inside an installa- AUTHORITY: 49 U.S.C. 20103, 20107, 20148 and tion that is not part of the general rail- 21301; 28 U.S.C. 2461, note; and 49 CFR 1.49. road system of transportation; (b) Rapid transit operations in an SOURCE: 70 FR 62176, Oct. -

Chapter Iv Working of Trains Generally A. Timing and Running of Trains

90 WORKING OF TRAINS GENERALLY CHAPTER IV WORKING OF TRAINS GENERALLY A. TIMING AND RUNNING OF TRAINS 4.01. STANDARD TIME. - The working of trains between stations shall be regulated by the standard time prescribed by the Government of India, which shall be transmitted daily to all the principal stations of the Railway at 16.00 hours in the manner prescribed. S.R. 4.01. The Section Controller on duty at 16.00 hrs. shall transmit the time signal to the stations in the section controlled by him. In case the duty of the Section Controller changes at 16.00 hrs. the outgoing Section Controller shall transmit the signal. In the non controlled section, the signal shall be transmitted by the controlling station. 4.02. ADHERENCE TO ADVERTISED TIME. - No passenger train or mixed train shall be despatched from a station before the advertised time. 4.03. SETTING WATCH. - Before a train starts from a terminal or crew-changing station, the Guard shall set his watch by the station clock or the clock at the authorised place of reporting for duty and communicate the time to the Driver who shall set his watch accordingly. 4.04. TIME OF ATTENDANCE FOR TRAIN CREW. - Every Guard, Driver, Assistant Driver or Fireman shall be in attendance for duty at such place and at such time as may be prescribed by special instructions. S.R. 4.04.(1) Attendance of Guards:- (a) where trains originate- (i) Guards of Passenger Trains shall report for duty 30 minutes and those of Through Goods Trains 45 minutes before booked departure of their trains. -

An Analysis of Soviet Railway Operation

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Freight Transportation in the Soviet Union: A Comparison with the United States Volume Author/Editor: Ernest W. Williams, Jr. Volume Publisher: Princeton University Press Volume ISBN: 0-87014-379-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/will59-1 Publication Date: 1959 Chapter Title: An Analysis of Soviet Railway Operation Chapter Author: Ernest W. Williams, Jr. Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2517 Chapter pages in book: (p. 89 - 132) CHAPTER 4 An Analysis of Soviet Railway Operation The Nature of Soviet Railway Operations USEFULNESS OF STUDY Of the several forms of transport, the railways alone afford a body of interrelated data that permit some internal check upon the probable accuracy of the published figures and also make possible an analysis of the methods by which the traffic performance is achieved.' Moreover, at least something is known of the source of many of these data; hence an impression can be formed of the character of the error which they may reflect and occasionally some judgment of its magnitude can be risked. This is of particular importance since the railways account for by far the greatest part of freight and passenger traffic and it is around the railways' returns that there has been the greatest con- troversy in Western countries. • Distrust has been generated by performance factors, particularly car turnaround, which may be viewed as impossible by Western standards. But, in general, the superficial picture is one of a traffic so large as to be inconsistent with the relatively small railway plant operated—small in mileage as well as in motive power and equipment. -

Taskload Report Outline

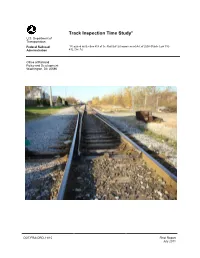

Track Inspection Time Study* U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad * Required by Section 403 of the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110- Administration 432, Div. A.) Office of Railroad Policy and Development Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-11/15 Final Report July 2011 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers‘ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

Military Railways

PROFESSIONAL PAPERS, No. 32 CORPS OF ENGINEERS, U. S. ARMY MILITARY RAILWAYS BY MAJ. W. D. CONNOR CORPS OF ENGINEERS V REVISED EDITION :916 Reviewed and Approved by the Board on Engineer Troops WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 WAR DEPARTMENT Document No 539 Office 0/the Chief of Engineers WAR DEPARTMENT, OFFICE 05' THE CHIEF OP STAFF, Washington, May 5, 1915. The following Manual of Military Railways, prepared by Maj. William D. Connor, Corps of Engineers, is approved and published for the information and government of the Regular Army and the Organized Militia of the United States.It is intended to supplement Part IV, Military Railways, of the Engineer Field Manual (Pro- fessional Papers No. 29, Corps of Engineers). By order of the Secretary of War: TASKER H. BLISS, Major General, Acting Chief of Sf aff. 3 . MILITARY RAILROADS. COMBAT RAILWAYS. 1. The subject of military railroads as here treated willinclude the location, construction, operation, and maintenance of railroads in the theaterof war under military auspices and for military purposes; that is, with apersonnel consisting of officers, enlisted men, and civilian employees, and for the main purposeof facilitat- ing the movements and supply of the Army. The difference between war and peace conditions will cause awide departure of military from civil railroad practice.Some of the conditions of military railroad earvice are: (a) Quick results for a short period are of the first consideration. (t) The mechanical possibilities of the property can not befully developed by reason of an untrained personnel. Speed requirements are moderate and practically uniform for alltraffic. -

Employment Outlook in Railroad Occupations

Qualificati Outlook Earnings Working C UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS Maurice J. Tobin, Secretary Ewan Clague, Commissioner OCCUPATIONAL OUTLOOK SERIES BULLETIN No. 961 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Cover picture shows brakeman signaling to engineer. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Employment Outlook in RAILROAD OCCUPATIONS Bulletin No. 961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR Maurice J. Tobin, Secretary BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS Ewan Clague, Commissioner UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1949 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 30 cents Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Letter of Transmittal U n it e d S tates D e pa r t m e n t oe L abor, B u r e a u of L abor S t a t ist ic s, Washing ton, D. G., June SO, 194,9. The S ec r eta r y of L abor : I have the honor to transmit herewith a report on the employment outlook in railroad occupations. This is one of a series of occupational studies pre pared in the Bureau’s Occupational Outlook Branch for use in vocational counseling of young people in school, veterans, and others interested in choosing a field of work. The study was conducted under the supervision of Helen Wood. The report was prepared by Miss Wood, Gloria Count, and Raymond D. Larson. Samuel Vernoff assisted in the field work; Sylvia K. -

Proper Car Placement in Trains

Proper Car Placement in Trains Presented by DuPage Division Midwest Region NMRA . Presented at Badgerland Express Madison, Wisconsin JJam Introduction Some of you may wonder why it is important to know that cars can be placed in the wrong order in a train. And, why does this even matter on a model railroad? On a real railroad improper car placement can cause embarrassing situations such as this .............. (Picture a train wreck.) Proper car placement also insures the general safety of.... The merchandise being transported The safety of the train crews handling the cars and the train The safety of the community thru which these cars may move. Some of these rules can be utilized to make the operation of your models more prototypical. The last reason I can think of for knowing this valuable information is that you can use it to heckle another modeler about his operation. ("Do you know that that tank car is in the wrong place in that train?") How do you know how to properly place cars in a train? There are a whole bunch of rulebooks. charts and other documents that trainmen must be familiar with when switching and operating trains. Every railroad has a "Book of Rules" which is the basis of this information. Superceding the "Book of Rules" is the Time Table and Special Instructions which is specific to a certain portion of the railroad. This is superceded by the System and General Bulletins. The most specific information is found in the Train Messages which are issued with every work order. Here is the hierarchy triangle: SYSTEM AND GENERAL BULLETINS TIME TABLE AND SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS GENERAL OPERATING RULES (BOOK) lets start with a few general rules to set the stage: Rule A Employees whose duties are governed by these rule must provide themselves with a copy of these rules... -

UPRR - General Code of Operating Rules

Union Pacific Rules UPRR - General Code of Operating Rules Seventh Edition Effective April 1, 2020 Includes Updates as of September 28, 2021 PB-20280 1.0: GENERAL RESPONSIBILITIES 2.0: RAILROAD RADIO AND COMMUNICATION RULES 3.0: Section Reserved 4.0: TIMETABLES 5.0: SIGNALS AND THEIR USE 6.0: MOVEMENT OF TRAINS AND ENGINES 7.0: SWITCHING 8.0: SWITCHES 9.0: BLOCK SYSTEM RULES 10.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN CENTRALIZED TRAFFIC CONTROL (CTC) 11.0: RULES APPLICABLE IN ACS, ATC AND ATS TERRITORIES 12.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN AUTOMATIC TRAIN STOP SYSTEM (ATS) TERRITORY 13.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN AUTOMATIC CAB SIGNAL SYSTEM (ACS) TERRITORY 14.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY WITHIN TRACK WARRANT CONTROL (TWC) LIMITS 15.0: TRACK BULLETIN RULES 16.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN DIRECT TRAFFIC CONTROL (DTC) LIMITS 17.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN AUTOMATIC TRAIN CONTROL (ATC) TERRITORY 18.0: RULES APPLICABLE ONLY IN POSITIVE TRAIN CONTROL (PTC) TERRITORY GLOSSARY: Glossary For business purposes only. Unauthorized access, use, distribution, or modification of Union Pacific computer systems or their content is prohibited by law. Union Pacific Rules UPRR - General Code of Operating Rules 1.0: GENERAL RESPONSIBILITIES 1.1: Safety 1.1.1: Maintaining a Safe Course 1.1.2: Alert and Attentive 1.1.3: Accidents, Injuries, and Defects 1.1.4: Condition of Equipment and Tools 1.2: Personal Injuries and Accidents 1.2.1: Care for Injured 1.2.2: Witnesses 1.2.3: Equipment Inspection 1.2.4: Mechanical Inspection 1.2.5: Reporting 1.2.6: Statements 1.2.7: Furnishing Information -

Rail Transit Track Inspection and Maintenance

APTA STANDARDS DEVEL OPMENT PROGRAM APTA RT-FS-S-002-02, Rev. 1 STANDARD First Published: Sept. 22, 2002 American Public Transportation Association First Revision: April 7, 2017 1300 I Street, NW, Suite 1200 East, Washington, DC 20006 Rail Transit Fixed Structures Inspection and Maintenance Working Group Rail Transit Track Inspection and Maintenance Abstract: This standard provides minimum requirements for inspecting and maintaining rail transit system tracks. Keywords: fixed structures, inspection, maintenance, qualifications, rail transit system, structures, track, training Summary: This document establishes a standard for the periodic inspection and maintenance of fixed structure rail transit tracks. This includes periodic visual, electrical and mechanical inspections of components that affect safe and reliable operation. This standard also identifies the necessary qualifications for rail transit system employees or contractors who perform periodic inspection and maintenance tasks. Scope and purpose: This standard applies to transit systems and operating entities that own or operate rail transit systems. The purpose of this standard is to verify that tracks are operating safely and as designed through periodic inspection and maintenance, thereby increasing reliability and reducing the risk of hazards and failures. This document represents a common viewpoint of those parties concerned with its provisions, namely operating/ planning agencies, manufacturers, consultants, engineers and general interest groups. The application of any standards, recommended practices or guidelines contained herein is voluntary. In some cases, federal and/or state regulations govern portions of a transit system’s operations. In those cases, the government regulations take precedence over this standard. The North American Transit Service Association (NATSA) and its parent organization APTA recognize that for certain applications, the standards or practices, as implemented by individual agencies, may be either more or less restrictive than those given in this document.