The Seniority Structure of Sovereign Debt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

JUDGMENT CLAIMS IN RECEIVERSHIP PROCEEDINGS* JOHN K. BEACH Connecticuf Supreme Court of Errors In view of the importance of the subject it is unfortunate that so few of the reported cases on equitable receiverships of corporations have dealt in any comprehensive way with the principles underlying the administrating of the fund for the benefit of creditors. The result is that controversy has outstripped authoritative decision, and the subject is unsettled. To this generalization an exception must be noted in respect of the special topic of the application of current rail- way income to current expenses, before the payment of mortgage 1 indebtedness. On another disputed topic, the provability of imma.ure claims, the law, or at least the right principle of decision, has been settled, by the notable opinion of Judge Noyes in Pennsylvania Steel Company v. New York City Railway Company,2 followed and rein- forced by that of Mr. Justice Holmes in William Filene'sSons Company v. Weed.' Notwithstanding these important exceptions, the dearth of authority on the general subject is such that Judge Noyes refers to a case cited in his opinion as "almost the only case in which rules have "been formulated with respect to the provability of claims against "insolvent corporations."4 Upon the particular phase of the subject here discussed, the decisions are to some extent in conflict, and no attempt seems to have been made in text books or decisions to examine the question in the light of principle. Black, for example, dismisses the subject by saying it. is generally conceded that a receiver and the corporation whose property is under his charge "are so far in privity that a judgment against the * This paper deals only with judgments against the defendant in the receiver- ship, regarded as evidence of the validity and amount of the judgment creditor's claims for dividends to be paid out of the fund in the receiver's hands. -

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

Members of Grace Road Church Have Seen, Heard, Abelieved, Understood and Acted According to the Bible

1st Edition 22 Apr 2019 1st Issue 22 Apr 2019 Author Grace Road Church Published by Grace Road Church Publishing Grace Road Mission Address 115, Chusa-ro, Gwacheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea Tel Korea (+82)2-503-9101 ISBN 979-11-950188-6-4 Contact Address Lot 11, Wainidova Road, Navua, Fiji Tel Fiji (+679)930-5687 E-mail [email protected] Website www.gr-church.org YouTube www.youtube.com/GodsWorld Copyright© 2019 by Grace Road Church All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Contents PREFACE 04 I Defend the Case of the Widow Indeed 08 II Defend the Members of Grace Road Church 58 Annex I Study on Reverend Esther of Grace Road Church 86 [SOURCE] https://blog.naver.com/queenpia/221118498294 WRITER | Queenpia Annex II Perspective on the Threshing Floor at Grace Road Church 95 [SOURCE] https://blog.naver.com/queenpia/221353050781 WRITER | Queenpia Letters to Reverend Esther 108 PREFACE Grace Road Church's Reverend Esther Shin has been interpreting the Scripture with the Scripture. She was the only one to state that the mysteries of the kingdom of God can only be revealed by interpreting the entire Bible from Genesis to Revelation as one whole. She has been revealing the Truth, which had been hidden from before time began, from the year 2008. Reverend Esther has been shedding light on the lies that differ from the Bible, which have been rampant even 2000 years after Jesus Christ died on the cross, resurrected and ascended to heaven. -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

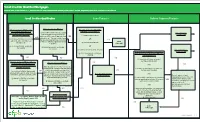

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

HELP OTHERS DISCOVER the GRACE of GIVING a Guide to Stewardship Campaigns That Touch the Heart

HELP OTHERS DISCOVER THE GRACE OF GIVING A guide to stewardship campaigns that touch the heart. WHAT'S INSIDE: HOW ARE WE GOING TO MAKE THIS PROJECT HAPPEN? ....................................................................................................................................0...3. THE 4 PHASES OF A STEWARDSHIP CAMPAIGN ..........................................................................................................................0...4....-..0....8. READINESS REVIEW ...................................................................................................................................0....4. LEADERSHIP PHASE ....................................................................................................................................0...5. PUBLIC PHASE ...................................................................................................................................0....6. FULFILLMENT PHASE ...................................................................................................................................0....7. SAMPLE STEWARDSHIP LETTERS .............................................................................................................................0....9...-..1..1 THE GENEROUS DONOR ....................................................................................................................................0....9 THE MID-LEVEL DONOR 10 ....................................................................................................................................... -

Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich

Cornell Law Review Volume 19 Article 3 Issue 1 December 1933 Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Chester Rohrlich, Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations, 19 Cornell L. Rev. 35 (1933) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol19/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREDITOR CONTROL OF CORPORATIONS; OPERATING RECEIVERSHIPS; COR- PORATE REORGANIZATIONS* CHESTER RoHRmicnt A corporation is, on a smaller scale (in some instances on a larger scale), like the political state, in that beneath the cloak of its unity there is a continuous, at times active but more frequently passive, struggle for power among the various groups in interest. Some of these groups, such as the public that deals with it or the employees who work for it, have as yet achieved only the the barest minimum of legal right to control its destinies.' In the arena of the law, the traditional conflict is between the stockholders2 and the creditors. There is an increasing convergence of interest between these two groups as the former become more and more "investors" rather than entrepreneurs, and the latter less and less inclined, or able, to stand on the letter of their bond'3 both are in the last analysis dependent *This article is the substance of one of the chapters of the author's forthcoming book THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF CORPORATE CONTROL. -

Database of Sovereign Defaults, 2017 by David Beers and Jamshid Mavalwalla

Technical Report No. 101 / Rapport technique no 101 Database of Sovereign Defaults, 2017 by David Beers and Jamshid Mavalwalla June 2017 (An earlier version of this technical report was published in June 2016.) Database of Sovereign Defaults, 2017 David Beers1 and Jamshid Mavalwalla2 1Special Advisor, International Directorate Bank of England London, United Kingdom EC2R 8AH [email protected] 2Funds Management and Banking Department Bank of Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0G9 [email protected] The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank of Canada. ISSN 1919-689X © 2017 Bank of Canada Acknowledgements We are grateful to Allan Crawford, Grahame Johnson, Philippe Muller, Peter Youngman, Carolyn A. Wilkins, John Chambers, Stuart Culverhouse, Archil Imnaishvili, Marc Joffe, Mark Joy and James McCormack for their helpful comments and suggestions, to Christian Suter for sharing with us previously unpublished data he compiled with Volker Bornschier and Ulrich Pfister in 1986, and to Jean-Sébastien Nadeau for his many contributions to this and earlier versions of the technical report and the database. We thank Norman Yeung and Isabelle Brazeau for their able technical assistance, and Glen Keenleyside, Meredith Fraser-Ohman and Carole Hubbard for their excellent editorial assistance. Any remaining errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. i Abstract Until recently, there have been few efforts to systematically measure and aggregate the nominal value of the different types of sovereign government debt in default. To help fill this gap, the Bank of Canada’s Credit Rating Assessment Group (CRAG) has developed a comprehensive database of sovereign defaults posted on the Bank of Canada’s website. -

Unfinished Business in the International Dialogue on Debt

CEPAL REVIEW 81 65 Unfinished business in the international dialogue on debt Barry Herman Chief, Policy Analysis and Development, From November 2001 to April 2003, the International Financing for Development Office, Monetary Fund grappled with a radical proposal, the Department of Economic Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism, for handling the and Social Affairs, United Nations external debt of insolvent governments of developing and [email protected] transition economies. That proposal was rejected, but new “collective action clauses” that address some of the difficulties in restructuring bond debt are being introduced. In addition, IMF is developing a pragmatic and eclectic approach to assessing debt sustainability that can be useful to governments and creditors. However, many of the problems in restructuring sovereign debt remain and this paper suggests both specific reforms and modalities for considering them. DECEMBER 2003 66 CEPAL REVIEW 81 • DECEMBER 2003 I Introduction A new sense of calm descended on the international international financial markets and government issuers markets for emerging-economy debt in mid-2003. The alike have accepted them. They address certain concerns calm was seen in rising international market prices of about how the external bond debt of crisis countries is sovereign bonds of emerging economies in the first half restructured, although some market participants of the year and good sales of new bond issues, in discount the likelihood that those concerns were any particular those of Brazil and Mexico, as well as the more than theoretical difficulties. This paper will argue successful completion of Uruguay’s bond exchange that the changes that were adopted leave unresolved offer. -

Miss Julie by August Strindberg

MTC Education Teachers’ Notes 2016 Miss Julie by August Strindberg – PART A – 16 April – 21 May Southbank Theatre, The Sumner Notes prepared by Meg Upton 1 Teachers’ Notes for Miss Julie PART A – CONTEXTS AND CONVERSATIONS Theatre can be defined as a performative art form, culturally situated, ephemeral and temporary in nature, presented to an audience in a particular time, particular cultural context and in a particular location – Anthony Jackson (2007). Because theatre is an ephemeral art form – here in one moment, gone in the next – and contemporary theatre making has become more complex, Part A of the Miss Julie Teachers’ Notes offers teachers and students a rich and detailed introduction to the play in order to prepare for seeing the MTC production – possibly only once. Welcome to our new two-part Teachers’ Notes. In this first part of the resource we offer you ways to think about the world of the play, playwright, structure, theatrical styles, stagecraft, contexts – historical, cultural, social, philosophical, and political, characters, and previous productions. These are prompts only. We encourage you to read the play – the original translation in the first instance and then the new adaptation when it is available on the first day of rehearsal. Just before the production opens in April, Part B of the education resource will be available, providing images, interviews, and detailed analysis questions that relate to the Unit 3 performance analysis task. Why are you studying Miss Julie? The extract below from the Theatre Studies Study Design is a reminder of the Key Knowledge required and the Key Skills you need to demonstrate in your analysis of the play. -

The Grace Tully Collection - Open and Online

Onnews and notes from Our the franklin d. roosevelt presidential Way library and museum with support from the Roosevelt Institute The Grace Tully Collection - Open and Online FDR PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY he FDR Presidential Library, over enactment in February 2010 of Public Law family; and a June 1933 handwritten letter Tthe course of eight months, acquired 111-138, sponsored in the Senate by Senator from Mussolini expressing his deep gratitude a significant collection of Roosevelt-era Charles Schumer (D-NY) and in the House and admiration to the President. Il Duce also papers, opened these materials to the public by Representative Louise Slaughter (D-NY). expresses his hope that he and FDR might for research and made the entire collection Sun Times is a successor to Hollinger Inter- meet one day to “discuss the outstanding available on the Library’s web site. national, whose CEO, Conrad Black, had world problems in which the United States purchased the Tully Collection and authored, and Italy are mutually interested.” The Tully Collection is an archive of original Franklin D. Roosevelt: Champion of Freedom. FDR-related papers and memorabilia that On November 15, 2010, the Grace Tully had been in the possession of the President’s Interesting documents in the collection Collection was officially opened to research- last personal secretary, Miss Grace Tully. include a 1936 FDR “chit” regarding the ers at the Roosevelt Library, and the entire This donation to the Roosevelt Library is promotion of George C. Marshall to Brigadier collection was digitized and made available the result of more than five years of negotia- General; a handwritten list by FDR indicat- online in March of 2011. -

Sovereigns in Distress: Do They Need Bankruptcy?

MICHELLE J. WHITE University of California, San Diego Sovereigns in Distress: Do They Need Bankruptcy? SHOULD THERE BE a sovereign bankruptcy procedure for countries in financial distress? This paper explores the use of U.S. bankruptcy law as a model for a sovereign bankruptcy procedure and asks whether adoption of such a procedure would lead to a more orderly process of sovereign debt restructuring. It assumes that a quick and orderly debt restructuring process is more efficient than a prolonged and disorderly one, because a lengthy process of debt restructuring takes a high toll on debtor countries’ economies as well as harming creditors in general. I concentrate on three goals for a sovereign bankruptcy procedure: preventing individual credi- tors or groups of creditors from suing the debtor for repayment, prevent- ing groups of creditors from strategically delaying negotiations or acting as holdouts, and increasing the likelihood that private creditors will pro- vide new loans to sovereign debtors in financial distress, thus reducing the pressure on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to fund bailouts. I conclude that nonbankruptcy alternatives are less likely to accomplish these goals than a sovereign bankruptcy procedure. U.S. Bankruptcy Law and Important Trade-offs in Bankruptcy Three sections of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code are of possible relevance for a future international bankruptcy procedure: Chapter 7 (bankruptcy I am grateful to Edwin Truman and Marcus Miller for helpful comments and discussion. 1 2 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1:2002 liquidation), Chapter 11 (corporate reorganization), and Chapter 9 (munic- ipal bankruptcy). Chapter 7 Chapter 7 is the U.S.