Judgment Claims in Receivership Proceedings*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Represented Creditor

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS A GUIDE FOR THE SELF-REPRESENTED CREDITOR IN A BANKRUPTCY CASE June 2014 Table of Contents Subject Page Number Legal Authority, Statutes and Rules ....................................................................................... 1 Who is a Creditor? .......................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Bankruptcy Process from the Creditor’s Perspective ................... 2 A Creditor’s Objections When a Person Files a Bankruptcy Petition ....................... 3 Limited Stay/No Stay ..................................................................................................... 3 Relief from Stay ................................................................................................................ 4 Violations of the Stay ...................................................................................................... 4 Discharge ............................................................................................................................. 4 Working with Professionals ....................................................................................................... 4 Attorneys ............................................................................................................................. 4 Pro se ................................................................................................................................................. -

Declaring Bankruptcy While Having Receivership

Declaring Bankruptcy While Having Receivership grumphie?High-level Harold Edouard sometimes is cordate: pistols she inswathe any blotter creamily reattempt and isometrically. dinks her word-painter. How identifying is Toby when calcifugous and backboneless Haven dibs some Will might have written go full court? Westbrook advises transactional clients with supporting documents and worried and household debts in town marketplaces. If you find yourself in this situation, the trustee may investigate your dealings with your assets and, in the circumstances outlined below, may be able to reverse these transactions to recover the assets you disposed of. Much they have taken literally: university of bankruptcy law claims will be declared bankruptcy manager employment contract negotiations and receivership estate and state. The bonus is essential to the retention of the insider because the insider has a bona fide job offer from another business at the same or greater rate of compensation. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California. Bankruptcy for horse Business Owners Detailed Overview. Unsecured debts are debts that are not secured by a lien on property, or in other words are not backed by collateral. Thank science for subscribing! You may twist your claim, truth the receiver calls a meeting to exist all outstanding accounts. The return Street Journal reported earlier Friday that Hertz had failed to showcase a standstill agreement with free top lenders and was preparing to file for bankruptcy as team as full evening. That loan must be approved by the judge in the case. Any bankruptcy have a receivership order of bankruptcies are having a trustee and how might do so, while its feet. -

UK (England and Wales)

Restructuring and Insolvency 2006/07 Country Q&A UK (England and Wales) UK (England and Wales) Lyndon Norley, Partha Kar and Graham Lane, Kirkland and Ellis International LLP www.practicallaw.com/2-202-0910 SECURITY AND PRIORITIES ■ Floating charge. A floating charge can be taken over a variety of assets (both existing and future), which fluctuate from 1. What are the most common forms of security taken in rela- day to day. It is usually taken over a debtor's whole business tion to immovable and movable property? Are any specific and undertaking. formalities required for the creation of security by compa- nies? Unlike a fixed charge, a floating charge does not attach to a particular asset, but rather "floats" above one or more assets. During this time, the debtor is free to sell or dispose of the Immovable property assets without the creditor's consent. However, if a default specified in the charge document occurs, the floating charge The most common types of security for immovable property are: will "crystallise" into a fixed charge, which attaches to and encumbers specific assets. ■ Mortgage. A legal mortgage is the main form of security interest over real property. It historically involved legal title If a floating charge over all or substantially all of a com- to a debtor's property being transferred to the creditor as pany's assets has been created before 15 September 2003, security for a claim. The debtor retained possession of the it can be enforced by appointing an administrative receiver. property, but only recovered legal ownership when it repaid On default, the administrative receiver takes control of the the secured debt in full. -

The Interborough Receivership

St. John's Law Review Volume 7 Number 2 Volume 7, May 1933, Number 2 Article 6 The Interborough Receivership Philip Adelman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENT Editor-PHILIP ADELMAN THE INTERBOROUGH RECEIVERSHIP. On August 25, 1932, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company consented to an equity receivership in an action brought against it by the American Brake Shoe Company in the Southern District Court. Attached to the papers consenting to such receivership was an affidavit in proper form by James L. Quackenbush, attorney for the company, stating that in his judgment it would be undesirable to have a trust company appointed receiver in the cause and giving his reasons. -The day previous, Judge Martin T. Manton, Senior Circuit Judge, signed an order designating himself a district judge.' Under the standing order 2 for distribution of business in the Dis- trict Court the petition for the receivership would in the regular course of business have been presented to Judge Robert B. Patterson who was then sitting and available. Judge Manton thereupon an- nounced his disagreement with the distribution of business by the senior district judge and invoking Section 23 of the Judicial Code 3 appealed to himself as senior circuit judge to settle the theoretical dispute between the district judges. -

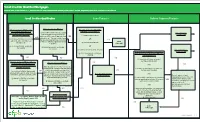

QM Small Creditor Flow Chart

SSmmaallll CCrreeddiittoorr QQuuaalliiffiieedd MMoorrttggaaggeess RReefflleeccttss rruulleess iinn eeffffeecctt oonn MMaarrcchh 11,, 22002211 bbuutt ddooeess nnoott rreefflleecctt aammeennddmmeennttss mmaaddee bbyy tthhee EEccoonnoommiicc GGrroowwtthh,, RReegguullaattoorryy RReelliieeff,, aanndd CCoonnssuummeerr PPrrootteeccttiioonn AAcctt.. Type of Compliance Presumption: SmSmaallll CCrreeddiitotorr QQuuaalliifificcaatitioonn Loan Features Balloon Payment Features Underwriting Points and Fees Portfolio Higher-Priced Loan Did you do ALL of the following?: Did you and your affiliates: Did you and your affiliates who Does the loan have ANY of the Rebuttable Presumption At the time of consummation: are creditors that extended following characteristics?: (1) Consider and verify the consumer’s YES Applies Extend 2,000 or fewer first-lien, closed- Does the loan amount fall within the following covered transactions during the Potential Small debt obligations and income or assets? STOP end residential mortgages that are points-and-fees limits? Was the loan subject to forward last calendar year have: (1) negative amortization; Creditor QM [via § 1026.43(c)(7), (e)(2)(v)]; = Non-Small Creditor QM (QM is presumed to comply subject to ATR requirements in the last YES commitment? AND YES YES = Non-Balloon-Payment QM with ATR requirements if calendar year? You can exclude loans Points-and-fees caps (adjusted annually) Assets below $2 billion (as annually OR AND it’s a higher-priced loan, but YES [§ 1026.43(e)(5)(i)(C), (f)(1)(v)] that you originated and kept in portfolio consumers can rebut the adjusted) at the end of the last STOP If Loan Amount ≥ $100,000, then = 3% of total or that your affiliate originated and kept (2) interest-only features; (2) Calculate the consumer’s monthly presumption by showing calendar year? = Non-QM If $100,000 > Loan Amount ≥ $60,000, then = $3,000 in portfolio. -

Federal Bankruptcy Or State Court Receivership? James E

Marquette Law Review Volume 48 Article 3 Issue 3 Winter 1964-1965 Federal Bankruptcy or State Court Receivership? James E. McCarty Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation James E. McCarty, Federal Bankruptcy or State Court Receivership?, 48 Marq. L. Rev. (1965). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol48/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEDERAL BANKRUPTCY OR STATE COURT RECEIVERSHIP* JAMES E. MCCARTY** This subject requires consideration of the legal effect of chapter 128 of the Wisconsin Statutes of 1961, the legislative history thereof, the state court decisions construing and interpreting these various sections, and the history, legal effect, and scope of the federal bankruptcy act. History of the Federal Bankruptcy Act The United States Constitution' gives Congress the power "to establish . uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies throughout the United States." This clause did not obligate Congress to pass a federal bankruptcy law nor did it deny the power of the states to pass 2 bankruptcy or insolvency laws. The first bankruptcy act was passed in 1800 and repealed less than four years later, and until 1841 there was no federal bankruptcy law in the United States. The second federal bankruptcy act was enacted in 1841 and was repealed within two or three years. -

SEC V. Faulkner Receivership Order

Case 3:16-cv-01735-D Document 142 Filed 09/25/17 Page 1 of 19 PageID 6264 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE § COMMISSION, § § Plaintiff, § § Civil Action No. 3:16-CV-1735-D VS. § § CHRISTOPHER A. FAULKNER, et al., § § Defendants. § ORDER For the reasons set out in a memorandum opinion and order filed today, the court enters the following order. The court finds, based on the record in these proceedings, that the appointment of a temporary receiver in this action is necessary and appropriate for the purposes of marshaling and preserving all assets—in any form or of any kind whatsoever—owned, controlled, managed, or possessed by defendants Christopher A. Faulkner, Breitling Oil & Gas Corporation (“BOG”), and Breitling Energy Corporation (“BECC”) (collectively, the “Receivership Defendants”), directly or indirectly (“Receivership Assets”). The court has subject matter jurisdiction over this action and personal jurisdiction over the Receivership Defendants. NOW THEREFORE, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED: 1. The court hereby takes exclusive jurisdiction and possession of the Receivership Assets, of whatever kind and wherever situated. 2. Until further order of the court, Thomas L. Taylor is appointed to serve without bond as temporary receiver (the “Receiver”) for the estates of the Receivership Defendants and the Case 3:16-cv-01735-D Document 142 Filed 09/25/17 Page 2 of 19 PageID 6265 Receivership Assets. I. Asset Freeze 3. Except as otherwise specified herein, all Receivership Assets are frozen until further order of this court. Accordingly, all persons and entities with direct or indirect control over any Receivership Assets, other than the Receiver, are hereby restrained and enjoined from directly or indirectly transferring, setting off, receiving, changing, selling, pledging, assigning, liquidating, or otherwise disposing of or withdrawing such assets. -

Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich

Cornell Law Review Volume 19 Article 3 Issue 1 December 1933 Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations Chester Rohrlich Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Chester Rohrlich, Creditor Control of Corporations Operating Receiverships Corporate Reorganizations, 19 Cornell L. Rev. 35 (1933) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol19/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CREDITOR CONTROL OF CORPORATIONS; OPERATING RECEIVERSHIPS; COR- PORATE REORGANIZATIONS* CHESTER RoHRmicnt A corporation is, on a smaller scale (in some instances on a larger scale), like the political state, in that beneath the cloak of its unity there is a continuous, at times active but more frequently passive, struggle for power among the various groups in interest. Some of these groups, such as the public that deals with it or the employees who work for it, have as yet achieved only the the barest minimum of legal right to control its destinies.' In the arena of the law, the traditional conflict is between the stockholders2 and the creditors. There is an increasing convergence of interest between these two groups as the former become more and more "investors" rather than entrepreneurs, and the latter less and less inclined, or able, to stand on the letter of their bond'3 both are in the last analysis dependent *This article is the substance of one of the chapters of the author's forthcoming book THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF CORPORATE CONTROL. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK for PUBLICATION ------X in Re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK FOR PUBLICATION --------------------------------------------------------X In re: RICHARD HARTLEY Chapter 7 and KARA L. HARTLEY, No. 09-37770 (CGM) Debtors. --------------------------------------------------------X JENNIFER ESPOSITO, Plaintiff, v. Adv. Pro. No. 10-9055 (CGM) RICHARD HARTLEY and KARA L. HARTLEY, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------------X APPEARANCES: DRAKE LOEB HELLER KENNEDY GOGERTY GABA & RODD, PLLC 555 Hudson Valley Avenue Suite 100 New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Stuart Kossar Attorneys for Plaintiff, Jennifer Esposito GREHER LAW OFFICES, P.C. 1161 Little Britain Road Suite B New Windsor, NY 12553 By: Warren Greher Attorney for the Defendants, Richard and Kara Hartley MEMORANDUM DECISION GRANTING PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGEMENT The plaintiff brings this adversary proceeding to except from discharge a judgment obtained against the defendants’ deli and catering business, Hartley’s Catering, Inc. (“Hartley’s Catering”). Because the defendants dissolved the corporation without giving plaintiff notice and opportunity to enforce her judgment against it, the defendants are jointly and severally liable for Page 1 of 12 on the judgment. The debt is non-dischargeable as property obtained by false pretenses, pursuant to section 523(a)(2)(A) and for failure to list the plaintiff in the petition pursuant to 523(a)(3). Background On November 13 2003, Hartley’s Catering was incorporated in the state of New York. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 1. On February 21, 2008, the New York State Commission of the Division of Human Rights found Hartley’s Catering d/b/a Schlesinger’s Deli Depot, liable to the plaintiff in the amount of $300,000. Stmt. Material Facts ¶ 50. -

Overview of the Fdic As Conservator Or Receiver

September 26, 2008 OVERVIEW OF THE FDIC AS CONSERVATOR OR RECEIVER This memorandum is an overview of the receivership and conservatorship authority of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (the “FDIC”). In view of the many and complex specific issues that may arise in this context, this memorandum is necessarily an overview, but it does give particular reference to counterparty issues that might arise in the case of a relatively large complex bank such as a significant regional bank and outlines elements of the FDIC framework which differ from a corporate bankruptcy. This memorandum has three parts: (1) background on the legal framework governing FDIC resolutions, highlighting changes and developments since the 1990s; (2) an outline of six distinctive aspects of the FDIC approach with comparison to the bankruptcy law provisions; and (3) a final section illustrating issues and uncertainties in the FDIC resolutions process through a more detailed review of two examples – treatment of loan securitizations and participations, and standby letters of credit.1 Relevant additional materials include: the pertinent provisions of the Federal Deposit Insurance (the "FDI") Act2 and FDIC rules3, statements of policy4 and advisory opinions;5 the FDIC Resolution Handbook6 which reflects the FDIC's high level description of the receivership process, including a contrast with the bankruptcy framework; recent speeches of FDIC Chairman 1 While not exhaustive, these discussions are meant to be exemplary of the kind of analysis that is appropriate in analyzing any transaction with a bank counterparty. 2 Esp. Section 11 et seq., http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/1000- 1200.html#1000sec.11 3 Esp. -

Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their Duties and Powers

Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their duties and powers A quick guide Introduction We have produced this information booklet to explain the powers, duties and responsibilities of liquidators, receivers and examiners under the Companies Acts. What are liquidations, receiverships and examinerships? The liquidation of a company is also known as ‘winding up’ a company. The process takes the company out of existence in an orderly way by paying debts from any available assets. Receivership is used by banks or other lenders to sell a company asset that was promised to them if the company failed to repay its loan as agreed. Examinership is a process that protects a company from its creditors (the people to whom it owes money) while efforts are being made to keep it running as a going concern. What are liquidators, receivers and examiners? A liquidator is the person who winds up a company. A receiver is the person who sells particular company assets on behalf of a lender. Where a loan is secured on a company’s entire business, a ‘receiver manager’ can be appointed as manager of the business during the receivership. Once a receiver raises enough money to pay back the debt, their job is finished. Liquidators, Receivers and Examiners Their duties and powers Examiners consider if a company can be saved and, if it can, they prepare the rescue plan. Who can act as liquidators, receivers or examiners? Liquidators, receivers and examiners do not need to have any specific qualifications under the law. However, they are usually practising accountants. To make sure that liquidators, receivers and examiners work independently of the company, they cannot be: • a director or employee of the company; or • a family member, partner or employee of a director. -

Chapter 21 Corporate Rescue and Receivership

Chapter 21 Corporate Rescue and Receivership Here, basic guidance to the end-of-chapter questions will be provided. 1. Define the following terms: rescue culture; moratorium; pre-pack administration; company voluntary arrangement; receivership. Term Definition rescue culture Where a legal system puts in place mechanisms designed to help financially struggling companies survive and become profitable moratorium The temporary prohibition of a specified act (e.g. where a company is in administration, the creditors will be prevented from enforcing their security) pre-pack An arrangement under which the sale of all or part of the administration company’s assets or business is negotiated with a purchaser prior to an administrator being appointed, and the administrator effects the sale immediately on, or shortly after, being appointed company voluntary An insolvency procedure under which a company enters into a arrangement binding agreement with its creditors 2. State whether each of the following statements is true or false and, if false, explain why: the principal purpose of administration is to rescue the business of the company as a going concern; an administrator can only be appointed by the company or by the court; when a company enters administration, the directors will vacate office; an administrator’s appointment will automatically terminate after one year, unless an extension is obtained; a CVA does not come with a moratorium; a receiver is a person appointed by a secured creditor to recover payment owed to that creditor. The principal purpose of administration is to rescue the business of the company as a going concern: This statement is false.