Europe's Diplomacy on Public Display

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queens of the Stone Age 9

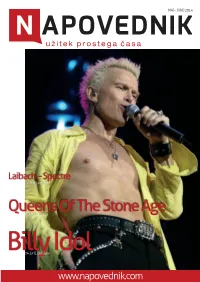

MAJ – JUNIJ 2014 Laibach – Spectre 16. maj, Ljubljana Queens Of The Stone Age 9. junij, Ljubljana Billy24. junij, Ljubljana Idol www.napovednik.com KAZALO 04 Ali že veste? 28 Prireditve Skuhna 06 Glasba 28 Skuhna – svetovna kuhinja po slovensko. Laibach Spectre ARTish 06 Preroki teme in apostoli noči v Križankah! 31 Prodajno-razstavni umetniški festival. Željko Bebek & Bend 06 Koncert v Cvetličarni ob 40-letnici delovanja. 32 Delavnice The Rolling Stones 07 Obisk treh koncertov organizirajo Koncerti.net. 36 Za otroke Queens of the Stone Age Mali raziskovalci morja 10 Po več kot desetih letih se vračajo v Ljubljano! 36 Raziskovalna avantura za otroke, stare od 6 do 12 let. Darko Brlek: Manj denarja, več muzike Družinski center Mala ulica 11 Intervju s prvim možem Festivala Ljubljana. 37 Javna dnevna soba za starše in otroke. 38 Kino Billy Idol 12 Slavni glasbenik junija prihaja v Halo Tivoli. Bajaga & Instruktori z gosti Komedija Sosedi 13 Veliki koncert ob 30-letnici legendarne skupine. 38 V kinematografih Cinneplexx bo teden dni pred drugimi! Punca ni nič kriva 16 Gledališče 38 Kino Šiška in Kinodvor pripravljata pin-up večer. Zeleni Jurij Možje X: Dnevi prihodnje preteklosti 16 Muzikal po ljudskih motivih. 40 Nadaljevanje sage o konfliktu med ljudmi in mutanti. Festival Prelet Zlohotnica 19 Mladinsko in Glej: pester program kar 15-ih predstav. 40 Angelina Jolie v akcijsko pustolovski drami. The Umbilical Brothers 21 V Siti Teater BTC se vračata slavna komika. 42 Avenija Mrtvec pride po ljubico 22 Predstava Svetlane Makarovič v PGK. 44 Mljask Dva koraka do hitrejšega metabolizma 26 Razstave 44 Pred obrokom naredite dve stvari … Emona: mesto v imperiju Recept 26 Razstava ob 2000-letnici urbane poselitve Ljubljane. -

Muzicki Program

MUZIČKI PROGRAM 2018 MAIN STAGE SUBOTA .. NEDELJA .. ČETVRTAK .. PETAK .. SREDA .. O RAINMAKER LOLE & RADI : - : : - : BLUES BAND THE FILTERS : - : HURLEUR IRON MAIDEN TRIBUTE : - : AERODROM : - : : - : FRAJLE : - : VIVA VOPS : - : ĐORĐE DAVID : - : RIBLJA ČORBA : - : BAND X : - : NEVERNE BEBE : - : YU GRUPA : - : E-PLAY : - : PARTIBREJKERS : - : DR NELE KARAJLIĆ : - : KIKI I PILOTI : - : DEJAN PETROVIĆ : - : ORTHODOX CELTS : - : LOLLOBRIGIDA : - : SIX PACK INSPEKTOR BLAŽA : - : : - : GOBLINI : - : LET I KLJUNOVI : - : ISKAZ INNOVATION STAGE NEDELJA .. PETAK .. SUBOTA .. SREDA .. ČETVRTAK .. BEND IZNENAĐENJA : - : SUNSHINE : - : THE STRANGLERS : - : VAN GOGH : - : RÓISÍN MURPHY : - : : - : BAD COPY ALTERNATIVE STAGE by NEDELJA .. PETAK .. SUBOTA .. SREDA .. ČETVRTAK .. BUNT : BUNT : BUNT : : - : : - : ALEJA VELIKANA MESIS : - : SERGIO LOUNGER BUNT : SITZPINKER : - : BUNT : NE SANJA TIŠMA I MASA : - : ARCTICK MONKEYS : - : VIS LIMUNADA : - : TRIBUTE OLA ČUTURILO : - : VATRA : - : FRAMEWORK : - : NIK : - : GILE & MAGIC BUSH STRAY DOGG : - : ZONA B STRAIGHT MICKEY : - : RIMLJANI ITE DOMA : - : : - : & THE BOYZ VELIKI PREZIR : - : NEŽNI DALIBOR : - : PEČITELJI : - : EX REVOLVERI : - : METALLICA TRIBUTE : - : PO PERO DEFFORMERO : - : ŠANK : - : ZOSTER : - : OBOJENI PROGRAM : - : M.O.R.T. : - : : - : KKN : - : BOLESNA ŠTENAD : - : ĐORĐE MILJENOVIĆ : - : LETU ŠTUKE DEPECHE TRIBUTE BAND : - : NBG : - : * ORGANIZATOR ZADRŽAVA PRAVO IZMENE PROGRAMA MUZIČKI PROGRAM 2018 INNOVATION ALTERNATIVE MAIN STAGE BY STAGE STAGE : - : BUNT : SITZPINKER : -

Vrijednosne Osobenosti Sevdalinke I Turbo-Folk Muzike Kao Muzičkih Izraza DHS 1 (14) (2021), 201-222

Kristina Prkić-Palavra, Izet Pehlić Vrijednosne osobenosti sevdalinke i turbo-folk muzike kao muzičkih izraza DHS 1 (14) (2021), 201-222 DOI 10.51558/2490-3647.2021.6.1.201 UDK 784.4:78.08 821.163.4(497.6):398.8 Primljeno: 18. 10. 2020. Pregledni rad Review paper Kristina Prkić-Palavra, Izet Pehlić VRIJEDNOSNE OSOBENOSTI SEVDALINKE I TURBO-FOLK MUZIKE KAO MUZIČKIH IZRAZA U radu se pošlo od činjenice utemeljene na uvidima u relevantne naučnoteorijske izvore da kontekstualni pristup muzici potcrtava da značenje u muzici nikad nije u potpunosti „čisto“, te se naglašavaju njezina funkcionalna vrijednost i osobenosti. Cilj ovog istraživanja bio je da se kroz komparativnu analizu tekstova sevdalinki i autorskih pjesama napisanih u duhu sevdalinke te tekstova pjesama turbo-folk muzike ustanove osobenosti i razlike ovih muzičkih izraza. U istraživanju se pošlo od pretpostavke da su osobenosti sevdalinke i turbo-folk muzike kao muzičkih izraza vrlo različite. Od istraživačkih metoda u radu su korišteni metod teorijske analize i metod analize sadržaja, a istraživački korpus činilo je 8 reprezentativnih pjesama sevdalinki i autorskih pjesama nastalih po uzoru na svedalinku te 8 pjesama turbo-folk muzike, koje su analizirane za potrebe izvođenja zaključaka. Rezultati istraživanja pokazali su kako sevdalinke i pjesme turbo-folk muzike promoviraju različite vrijednosti. Izveden je zaključak kako bi pozitivne vrijednosti koje promovira sevdalinka bi trebalo u većoj mjeri koristiti u odgojne svrhe. Ključne riječi: sevdalinka; turbo-folk; osobenosti; poruke; vrijednosti UVOD Danas je muzika dio životne svakodnevnice gotovo svakog čovjeka. S muzikom smo prirodno povezani, te čak i kada bismo htjeli ne bismo mogli izbjeći slušanje muzike. -

1 En Petkovic

Scientific paper Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1967 to 20031 UDC 811.163.41’322 DOI 10.18485/infotheca.2019.19.1.1 Ljudmila Petkovi´c ABSTRACT: The paper analyses the pro- [email protected] cess of creation and processing of the Yu- University of Belgrade goslav rock song lyrics corpus from 1967 to Belgrade, Serbia 2003, from the theoretical and practical per- spective. The data have been obtained and XML-annotated using the Python program- ming language and the libraries lyricsmas- ter/yattag. The corpus has been preprocessed and basic statistical data have been gener- ated by the XSL transformation. The diacritic restoration has been carried out in the Slovo Majstor and LeXimir tools (the latter appli- cation has also been used for generating the frequency analysis). The extraction of socio- cultural topics has been performed using the Unitex software, whereas the prevailing top- ics have been visualised with the TreeCloud software. KEYWORDS: corpus linguistics, Yugoslav rock and roll, web scraping, natural language processing, text mining. PAPER SUBMITTED: 15 April 2019 PAPER ACCEPTED: 19 June 2019 1 This paper originates from the author’s Master’s thesis “Creation and Analysis of the Yugoslav Rock Song Lyrics Corpus from 1945 to 2003”, which was defended at the University of Belgrade on March 18, 2019. The thesis was conducted under the supervision of the Prof. Dr Ranka Stankovi´c,who contributed to the topic’s formulation, with the remark that the year of 1945 was replaced by the year of 1967 in this paper. -

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk Kunstner Listen

Popmusik Musikgruppe & Musisk kunstner Listen Stacy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/stacy-3503566/albums The Idan Raichel Project https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/the-idan-raichel-project-12406906/albums Mig 21 https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/mig-21-3062747/albums Donna Weiss https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/donna-weiss-17385849/albums Ben Perowsky https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ben-perowsky-4886285/albums Ainbusk https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ainbusk-4356543/albums Ratata https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/ratata-3930459/albums Labvēlīgais Tips https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/labv%C4%93l%C4%ABgais-tips-16360974/albums Deane Waretini https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/deane-waretini-5246719/albums Johnny Ruffo https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/johnny-ruffo-23942/albums Tony Scherr https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/tony-scherr-7823360/albums Camille Camille https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/camille-camille-509887/albums Idolerna https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/idolerna-3358323/albums Place on Earth https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/place-on-earth-51568818/albums In-Joy https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/in-joy-6008580/albums Gary Chester https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/gary-chester-5524837/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums Hilde Marie Kjersem https://da.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/hilde-marie-kjersem-15882072/albums -

Poznati Učesnici Festivala "Omladina" Koji Će Biti Održan 07. I 08. Decembra

Poznati u česnici Festivala "Omladina" koji će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra Postavljeno: 21.10.2012 Posle dve decenije pauze i prošlogodišnje retrospektive jednog od najpopularnijih muzi čkih omladinskih festivala u bivšoj Jugoslaviji, Festival "Omladina" Subotica od ove godine će ponovo organizovati muzi čko takmi čenje i okupiti mlade autore iz nekoliko zemalja regiona. Festival će biti održan 07. i 08. decembra pod sloganom "Razli čitost koja spaja". Nostalgija Kako je saopšteno na konferenciji za novinare, na konkurs festivala pristigla su 193 rada iz Srbije, Crne Gore, BiH, Hrvatske, Slovenije, Makedonije, Ma đarske, i Bugarske, od kojih je odabrano 25 kompozicija koje će se na ći na finalnoj ve čeri Festivala Omladina 2012. Direktor festivala, kompozitor Gabor Len đel, najavio je da će o najboljim u česnicima odlu čivati internacionalini stru čni žiri koji će činiti Olja Deši ć iz Hrvatske, Tomaž Domicelj iz Slovenije, Brano Liki ć iz BiH i Peca Popovi ć iz Srbije. Len đel je najavio da će na Festivalu biti dodeljeno šest nagrada. "Takmi čarski deo festivala održa će se 8. decembra u 19 časova u Hali sportova, a u revijalnom delu nastupi će 'Bajaga i instruktori'. Prate ći program festivala uklju čuje 'Ve če nostalgije' koncertom Ibrice Jusi ća, 7. decembra u 19 časova u Velikoj ve ćnici Gradske ku će", kazao je on. Razli čiti muzi čki pravci Umetni čki direktor Festivala Kornelije Kova č izjavio je da će na festivalu biti zastupljeni razli čiti muzi čki pravci - od regea, preko popa i bluza, do repa. "Posebno raduje da smo ponovo uspeli da u festival uklju čimo ceo region jer na taj na čin ponovo uspostavljamo mostove koji su nekada bili porušeni. -

2009 08 12 AKTO 4 Catalog

279487115 АКТО_4 FESTIVAL FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTS TOPIC_GENERATIONS AKTO_4 Festival for Contemporary arts will be held from 12.08 - 16.08.09 in Bitola, Republic of Macedonia. Akto is a regional festival for contemporary art which includes visual arts, performing arts, music and theory of culture. The main objective of Akto Festival is to open the cultural frameworks of a modern society through “recomposing” and redifning them in a new context. The programme of the festival is based on two concepts. The frst concept is space/location_ Locations have been transformed in terms of their previous meanings. The basic idea of the festival is art pieces to come out of the standard location (galleries, museums, theatres) used for presenting art, and their setting up in new location. Re-moving of the pieces into new location transforms the piece itself (according to the parameter space). The second concept is the topic of the festival_ The topic of Akto_4 festival is Generations. The artistic pieces (according to the parameter Generations) are going to be presented in two categories: artistic pieces that have generations as a basic starting point and pieces that are transformation of an already fnished artistic forms (also according to the parameter Generations). The “new” piece is transformed from its basic form. It has new statics and dynamics. The topic Generations deals with the issue of generations and initiates several questions: Are the ties between today’s young generations with the generation of their parents broken? Are today’s young generations -

„Muzički Ukus Mladih U Sarajevu“

ODSJEK SOCIOLOGIJA „MUZIČKI UKUS MLADIH U SARAJEVU“ -magistarski rad- Kandidat Mentor Amina Memišević Doc. dr. Sarina Bakić Broj indexa: 323 Sarajevo, maj 2020 Sadržaj I Uvod ............................................................................................................................................. 5 II Teorijsko – metodološki okvir istraživanja ................................................................................. 6 1. Problem istraživanja ............................................................................................................... 6 2. Predmet istraživanja ............................................................................................................... 6 3. Teorijska osnova istraživanja ................................................................................................. 6 4. Ciljevi istraživanja .................................................................................................................. 7 4.1. Znanstveni (spoznajni) ciljevi istraživanja ....................................................................... 7 4.2. Društveni (pragmatički) ciljevi istraživanja ..................................................................... 7 5. Sistem hipoteza ........................................................................................................................ 7 5.1. Generalna hipoteza........................................................................................................... 7 5.2. Pomoćne (popratne) hipoteze .......................................................................................... -

Repertoar La LUNA Band-A Naziv Izvodjac STRANE PESME Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin the Girl from Ipanema Astrud Gilberto Stand by Me Ben E

Repertoar La LUNA band-a naziv Izvodjac STRANE PESME Chain of Fools Aretha Franklin The Girl from Ipanema Astrud Gilberto Stand by Me Ben E. King Summertime Billie Holiday,Ella Fitzgerald,Sarah Vaughan White Wedding Billy Idol Knockin' on heaven's Door Bob Dylan No Woman No Cry Bob Marley Let's Stick Together Bryan Ferry Chan Chan Buena Vista Social Club El Cuarto de Tula Buena Vista Social Club Veinte Anos Buena Vista Social Club Hasta siempre Comandante Che Guevara Carlos Puebla Dove l'amore Cher I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For Coco Freeman feat. U2 Just A Gigolo David Lee Roth Money For Nothing Dire Straits Long Train Running Doobie Brothers Gimme Hope Jo'Anna Eddy Grant Non, je ne regrette rien Edith Piaf Blue Spanish Eyes Elvis Presley Blue Suede Shoes Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley Viva Las Vegas Elvis Presley Love Me Tender Elvis Presley Besame mucho Emilio Tuero Please release Me Engelbert Humperdinck Change The World Eric Clapton Layla Eric Clapton Tears In Heaven Eric Clapton Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Malaika Fadhili Williams Easy Faith no More All of Me Frank Sinatra New York, New York Frank Sinatra Can't Take My Eyes Off You Frankie Valli Careless Whisper George Michael Nathalie Gilbert Becaud Baila me Gipsy Kings Bamboleo Gipsy Kings Repertoar La LUNA band-a naziv Izvodjac Trista Pena Gipsy Kings I will survive Gloria Gaynor Libertango Grace Jones I Feel Good James Brown Por Que Te Vas Javier Alvarez Autumn Leaves/Les feuilles mortes Jo Elizabeth Stafford;Yves Montand Unchain my Heart Joe Cocker -

Same Soil, Different Roots: the Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia

Same Soil, Different Roots: The Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia Una Bobinac A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in International Studies, Russian, Eastern European, Central Asian Studies University of Washington 2015 Committee: James Felak Daniel Chirot Bojan Belić Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies 2 @Copyright 2015 Una Bobinac 3 University of Washington Abstract Same Soil, Different Roots: The Use of Ethno-Specific Narratives During the Homeland War in Croatia Una Bobinac Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Felak History This work looks at the way interpretations and misrepresentations of the history of World War II changed and evolved and their ultimate consequence on the Homeland War in Croatia from 1991 to 1995 between the resident Serb and Croat populations. Explored are the way official narratives were constructed by the communist regime, how and why this narrative was deconstructed, and by more ethno-specific narratives prevailed that fueled the nationalist tendencies of the war. This paper is organized chronologically, beginning with the historical background that puts the rest of the paper into context. The paper also discusses the nationalist resurfacing before the war by examining the Croatian Spring, nationalist re-writings of history, and other matters that influenced the war. The majority of the paper analyzes the way WWII was remembered and dismembered during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s by looking at rhetoric, publications, commemorations, and the role of the Catholic and Serbian Orthodox Churches. Operation Storm, which was the climax of the Homeland War and which expelled 200,000 Serbs serves as an end-point. -

Domaće Popularne, Zabavne, Strane I Rok Pesme

DOMAĆE POPULARNE, ZABAVNE, STRANE I ROK PESME: o Aerodrom – Obična ljubavna pesma o Ambasadori – Dođi u 5 do 5 o Apsolutno Romantično – Đoletova pesma o Atomsko Sklonište – Olujni Mornar o Atomsko Sklonište – Pakleni vozači o Atomsko Sklonište – Za ljubav treba imat dušu o Azra – Balkan o Azra – Usne vrele višnje o Azra – Voljela me nijedna o Babe – Ko me ter’o o Babe – Noć bez sna o Baby Doll – Brazil o Bajaga – 220 u voltima o Bajaga – Godine prolaze o Bajaga – Moji su drugovi o Bajaga – Na vrhovima prstiju o Bajaga – Ti se ljubiš tako dobro o Bajaga – Tišina o Bajaga – Vratiće se rode o Bijelo Dugme – A i ti me iznevjeri o Bijelo Dugme – Ako ima Boga o Bijelo Dugme – Đurđevdan o Bijelo Dugme – Esma o Bijelo Dugme – Lažeš o Bijelo Dugme – Lipe cvatu o Bijelo Dugme – Na zadnjem sedištu moga auta o Bijelo Dugme – Napile se ulice o Bijelo Dugme – Padaju zvijezde o Bijelo Dugme – Pljuni i zapjevaj o Bijelo Dugme – Ružica si bila o Bijelo Dugme – Tako ti je mala moja kad ljubi o Boris Režak – Anđeo o Colonia – Ti da bu di bu da o Crvena Jabuka – Bacila je sve niz rijeku o Crvena Jabuka – Da nije ljubavi o Crvena Jabuka – Dirlija o Crvena Jabuka – Moje najmilije o Crvena Jabuka – Nekako s prolijeća o Crvena Jabuka – Stižu me sjećanja o Crvena Jabuka – Tamo gdje ljubav počinje o Crvena Jabuka – To mi radi o Crvena Jabuka – Tuga, ti i ja o Crvena Jabuka – Volio bi da si tu o Crvena Jabuka – Zovu nas ulice o Čutura – Voli me o Darko Domijan – Ulica jorgovana o Dado Topić I Slađana Milošević – Princeza o Dejan Cukić – Milica o Dejan Cukić – Nebo -

NACIONALNI FESTIVAL “FROGVILLE FEST“ Žabalj/Novi Sad/Zrenjanin, Srbija, 3

NACIONALNI FESTIVAL “FROGVILLE FEST“ Žabalj/Novi Sad/Zrenjanin, Srbija, 3. - 5. Jul 2014. ________________________________________________________________________ Marko Dorić 318M/13 Nataša Gajović 30M/13 Aleksa Dopuđa 389M/13 SADRŽAJ ŽABALJ .............................................................................................................................. 3 NOVI SAD ........................................................................................................................... 5 NOVOSADSKA ROK SCENA ........................................................................................ 8 ZRENJANIN..................................................................................................................... 10 ZRENJANINSKA ROK SCENA .................................................................................. 11 FROGVILLE FESTIVAL .................................................................................................. 13 DATUM ......................................................................................................................... 14 OPREMA I LOKACIJA ................................................................................................ 15 ORGANIZACIJA ........................................................................................................... 16 POGODNOSTI + BITNE + DODATNE INFORMACIJE ........................................... 16 KONFERENCIJA ............................................................................................................