Garde at the Maison Brummer, Paris (1908-1914)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Hamilton Easter Fiel

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 WE the Moderns: Gaudier and the Birth of Modern Sculpture

'WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 WE the moderns: Gaudier and the birth of modern sculpture 20 January - 18 March 2007 Information for teachers • What is the exhibition about? 2 • Key themes 3 • Who was Gaudier? 4 • Gaudier quotes 5 • Points of discussion 6 • Activity sheets 7-11 • Brief biography of the artists 12-18 1 'WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 What is the exhibition about? "WE the moderns: Gaudier-Brzeska and the birth of modern sculpture", explores the work of the French sculptor in relation to the wider continental context against which it matured. In 1911, aged 19, Gaudier moved to London. There he was to spend the rest of his remarkably concentrated career, which was tragically cut short by his death in the trenches four years later. These circumstances have granted the sculptor a rather ambiguous position in the history of art, with the emphasis generally falling on his bohemian lifestyle and tragic fate rather than on his artistic achievements, and then on his British context. The exhibition offers a fresh insight into Gaudier's art by mapping its development through a selection of works (ranging from sculptures and preparatory sketches to paintings, drawings from life, posters and archival material) aimed at highlighting not only the influences that shaped it but also striking affinities with contemporary and later work which reveal the artist's modernity. At the core of the exhibition is a strong representation of Gaudier's own work, which is shown alongside that of his contemporaries to explore themes such as primitivism, artists' engagement with the philosophy of Bergson, the rendition of movement and dynamism in sculpture, the investigation into a new use of space through relief and construction by planes, and direct carving. -

Michel PÉRINET

COLLECTION Michel PÉRINET Paris, 23 juin 2021 COLLECTION Michel PÉRINET COLLECTION Michel PÉRINET VENTE EN ASSOCIATION AVEC BERNARD DULON LANCE ENTWISTLE assisté de Marie Duarte-Gogat [email protected] Expert près la Cour d’Appel de Paris Tel: +44 20 7499 6969 Membre de la CNE [email protected] Tel: + 33 (0)1 43 25 25 00 ALAIN DE MONBRISON FRANÇOIS DE RICQLÈS assisté de Pierre Amrouche Commissaire-Priseur et Emilie Salmon [email protected] Expert honoraire près la Cour Tel: +33 (0)1 73 54 53 53 d’Appel de Paris [email protected] Tel: +33 (0)1 46 34 05 20 COLLECTION MICHEL PÉRINET 7 COLLECTION Michel PÉRINET Mercredi 23 juin 2021 - 16h 9, avenue Matignon 75008 Paris EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE Samedi 19 juin 10h-18h Dimanche 20 juin 14h-18h Lundi 21 juin 10h-18h Mardi 22 juin 10h-18h Mercredi 23 juin 10h-16h COMMISSAIRE-PRISEUR François de Ricqlès CODE ET NUMÉRO DE VENTE Pour tous renseignements ou ordres d’achats, veuillez rappeler la référence 19534 - PÉRINET RETRAIT DES LOTS CONDITIONS DE VENTE Pour tout renseignement, veuillez contacter La vente est soumise aux conditions générales imprimées en fin de catalogue. le département au +33 1 40 76 84 48. Il est vivement conseillé aux acquéreurs potentiels de prendre connaissance des informations importantes, avis et lexique figurant également en fin de catalogue. For any query, please contact the department at +33 1 40 76 84 48. The sale is subject to the Conditions of Sale printed at the end of the catalogue. Prospective buyers are kindly advised to read as well the important information, notices and explanation of cataloguing practice also printed at the end of the catalogue. -

Deux Chefs-D'œuvre De L'ancienne Collection

MÉDIA ALERTE ǀ PARIS ǀ 14 OCTOBRE 2015 ǀ POUR DIFFUSION IMMÉDIATE DEUX CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE L’ANCIENNE COLLECTION JACQUES DOUCET PROPOSÉS LORS DE LA VENTE DU SOIR ‘DESIGN’, À PARIS LE 23 NOVEMBRE 2015 Paris – Le 23 novembre prochain, au sein de sa vente du soir ‘Design’, Christie’s aura le plaisir de présenter deux chefs-d’œuvre inédits provenant de l’ancienne collection de Jacques Doucet : Tête de Lionne réalisée par Joseph Csaky et Sculpture Lumineuse exécutée par Gustave Miklos. Pauline De Smedt, directrice du département Design, Christie’s France : « Nous sommes très fiers de pouvoir présenter deux œuvres si rares à nos collectionneurs. Redécouvrir ces deux trésors, chacun pièce unique, jamais encore exposés au marché de l’art et bénéficiant de la provenance la plus prestigieuse, constitue un moment privilégié. Les amateurs de notre spécialité qui ne manqueront pas d’aller voir l’exposition consacrée à l’un de ses plus grands mécènes, Jacques-Doucet – Yves Saint Laurent, ouvrant ses portes le 15 octobre à la Fondation Pierre Bergé | Yves Saint Laurent, auront ainsi l’occasion de compléter leur visite en venant admirer ces deux œuvres phares de la vente du soir de Design du 23 novembre ». Joseph Csaky (1888-1971) nait en Hongrie et étudie à l’École des Arts Décoratifs de Budapest avant de s’installer à Paris en 1908. Son travail est d’abord influencé par le post-classicisme de Rodin puis par la rigueur sensuelle de Maillol. Très rapidement pourtant, le cubisme s'impose comme style dominant dans son œuvre, et Csaky explore également l'abstraction. -

Robert Lehman Papers

Robert Lehman papers Finding aid prepared by Larry Weimer The Robert Lehman Collection Archival Project was generously funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on September 24, 2014 Robert Lehman Collection The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028 [email protected] Robert Lehman papers Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note...................................................................................................34 Arrangement note.............................................................................................................. 36 Administrative Information ............................................................................................ 37 Related Materials ............................................................................................................ 39 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................. 41 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 40 Collection Inventory..........................................................................................................43 Series I. General -

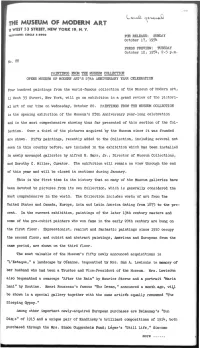

Paintings from Museum Collection with 4 Checklists

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ""^ V tt WIST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. TiiiPHONEt CIRCLE 5-8*oo pQP RELEASE: SUNDAY October 17, 195^ PRESS PREVIEW: TUESDAY October 12, 1951*, 2-5 p.m. No. 88 PAINTINGS FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION OPENS MUSEUM OF MODERN ART'S 25th ANNIVERSARY YEAR CELEBRATION Four hundred paintings from the world-famous collection of the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 55 Street, New York, will go on exhibition in a grand review of the pictori al art of our time on Wednesday, October 20. PAINTINGS FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION is the opening exhibition of the Museum's 25th Anniversary year-long celebration and is the most comprehensive showing thus far presented of this section of the Col lection. Over a third of the pictures acquired by the Museum since it was founded are shown. Fifty paintings, recently added to the Collection, including several not seen in this country before, are included in the exhibition which has been installed in newly arranged galleries by Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Director of Museum Collections, and Dorothy C. Miller, Curator. The exhibition will remain on view through the end of this year and will be closed in sections during January. This is the first time in its history that so many of the Museum galleries have been devoted to pictures from its own Collection, which is generally considered the most comprehensive in the world. The Collection includes works of art from the United States and Canada, Europe, Asia and Latin America dating from 1875 to the pre sent. -

The Salon of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture

The Salon of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture From 8 to 12 november 2017 Palais Brongniart 28 Place de la Bourse 75002 Paris www.finearts-paris.com Press contact : FAVORI - 233, rue Saint Honoré 75001 – T +33 1 42 71 20 46 1 Grégoire Marot - Nadia Banian [email protected] Summary page 03 FINE ARTS PARIS The Salon of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture Fair page 06 List of 34 exhibitors in alphabetical order page 40 General Information / Contact 2 FINE ARTS PARIS The Salon of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture Brongniart with FINE ARTS PARIS which will take place from 8 to 12 November 2017. From a Renaissance sculpture to an 18th century painting or a Cubist drawing, schools. Origin of the project: The organizers of this new fair are none other than those who created the Salon du Dessin, the international scope of which has contributed to making Paris one of the major centres for this domain. Because they believe in the future of Paris and in specialized fairs, they have decided to apply the fundamental principles and demands that governed the organization of the Salon du Dessin to this event: • the stands are drawn by lot; • a comfortable setting, conceived without ostentation and on a human scale; • a vetting committee comprised of well known specialists who are not exhibitors. and reveal the wealth of the three major disciplines, painting, drawing and sculpture which will be freely associated on each of the stands. Diversity and quality are the hallmarks of this new fair, whether in media, periods, subjects on view, but also budgets because museum quality works exhibited by major galleries can be shown alongside “discoveries” by young dealers presented at lower prices. -

Cubism and Australian Art and Its Accompanying Book of the Same Title Explore the Impact of Cubism on Australian Artists from the 1920S to the Present Day

HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Melinda Harper Untitled 2000 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased through the National Gallery of Victoria Foundation by Robert Gould, Benefactor, 2004 This Education Resource has been produced by Heide Museum of Modern Art to provide information to support education institution visits to the exhibition Cubism & Australian Art and as such is intended for their use only. Reproduction and communication is permitted for educational purposes only. No part of this education resource may be stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means. HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Heide Education is committed to providing a stimulating and dynamic range of quality programs for learners and educators at all levels to complement that changing exhibition schedule. Programs range from introductory tours to intensive forums with artists and other arts professionals. Designed to broaden and enrich curriculum requirements, programs include immersive experiences and interactions with art in addition to hands-on creative artmaking workshops which respond to the local environs. Through inspiring programs and downloadable support resources our aim is to foster deeper appreciation, stimulate curiosity and provoke creative thinking. Heide offers intensive and inspiring professional development opportunities for educators, trainee teachers and senior students. Relevant links to VELS and the VCE are incorporated into each program with lectures, floor talks and workshops by educators, historians and critics. Exclusive professional development sessions to build the capacity and capability of your team can be planned for your staff and potentially include exhibition viewings, guest speakers, catering, and use of the Sidney Myer Education Centre. If you would like us to arrange a PD just for your group please contact the Education Coordinator to discuss your individual requirements. -

Edward W. Root's Art Library Within a Year of His Death, Approximately

Edward W. Root’s Art Library Within a year of his death, approximately seven hundred art-related books and periodicals were transferred from Edward Root’s home in Clinton, N.Y. to the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute’s Art Reference Library. These volumes were part of a much larger collection Edward and Grace Root assembled during their lives. In 1919, the Institute’s founding charter called for the establishment of an “auxiliary library” to complement its museum, art school, and music programs, but around 1956 when Root died the collection numbered fewer than two thousand volumes. Root’s titles increased the size of the Institute’s library by approximately one third. This gift was mentioned in the Institute’s 1956-1957 year book and the Museum’s 1961 exhibition catalog, the Edward Wales Root Bequest. While not the largest donation the Institute’s library has ever received, Root’s collection is certainly one of the most valuable because it reflects the art- historical interests of an individual who played a key role in shaping the scope and character of the Museum’s permanent collection, as well as reinforcing the library’s role as a scholarly resource for research on the permanent collection. At the time of the bequest, no record was prepared of the titles Root gave the Institute. However, the following subject categories that were listed on a checklist of the thirty-eight packing cartons that were shipped from Clinton to the Institute provide an overview of Root’s wide-ranging interests: European painting and architecture; American art and architecture; European and American sculpture; prints and printmaking; “minor” arts; photography and film; “exotic” art; mixed media; art history, theory and criticism; and periodicals. -

Imogen Racz Volume 1

HENRI LAURENS AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE IMOGEN RACZ NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 099 19778 0 -' ,Nesis L6 VOLUME 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD. The University of Newcastle. 2000. Abstract This dissertation examines the development of Henri Laurens' artistic work from 1915 to his death in 1954. It is divided into four sections: from 1915 to 1922, 1924 to 1929, 1930 to 1939 and 1939 to 1954. There are several threads that run through the dissertation. Where relevant, the influence of poetry on his work is discussed. His work is also analyzed in relation to that of the Parisian avant-garde. The first section discusses his early Cubist work. Initially it reflected the cosmopolitan influences in Paris. With the continuation of the war, his work showed the influence both of Leonce Rosenberg's 'school' of Cubism and the literary subject of contemporary Paris. The second section considers Laurens' work in relation to the expanding art market. Laurens gained a number of public commissions as well as many ones for private clients. Being site specific, all the works were different. The different needs of architectural sculpture as opposed to studio sculpture are discussed, as is his use of materials. Although the situation was not easy for avant-garde sculptors, Laurens became well respected through exposure in magazines and exhibitions. The third section considers Laurens in relation to the depression and the changing political scene. Like many of the avant-garde, he had left wing tendencies, which found form in various projects, including producing a sculpture for the Ecole Karl Marx at Villejuif.