The Whisky Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perceptual Categorisation of Blended and Single Malt Scotch Whiskies Barry C

Smith et al. Flavour (2017) 6:5 DOI 10.1186/s13411-017-0056-x RESEARCH Open Access The perceptual categorisation of blended and single malt Scotch whiskies Barry C. Smith1*, Carole Sester2, Jordi Ballester3 and Ophelia Deroy1 Abstract Background: Although most Scotch whisky is blended from different casks, a firm distinction exists in the minds of consumers and in the marketing of Scotch between single malts and blended whiskies. Consumers are offered cultural, geographical and production reasons to treat Scotch whiskies as falling into the categories of blends and single malts. There are differences in the composition, method of distillation and origin of the two kinds of bottled spirits. But does this category distinction correspond to a perceptual difference detectable by whisky drinkers? Do experts and novices show differences in their perceptual sensitivities to the distinction between blends and single malts? To test the sensory basis of this distinction, we conducted a series of blind tasting experiments in three countries with different levels of familiarity with the blends versus single malts distinction (the UK, the USA and France). In each country, expert and novice participants had to perform a free sorting task on nine whiskies (four blends, four single malts, one single grain, plus one repeat) first by olfaction, then by tasting. Results: Overall, no reliable perceptual distinction was revealed in the tasting condition between blends and single malts by experts or novices when asked to group whiskies according to their similarities and differences. There was nonetheless a clear effect of expertise, with experts showing a more reliable classification of the repeat sample. -

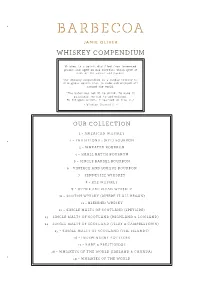

Whiskey Compendium

WHISKEY COMPENDIUM Whiskey is a spirit distilled from fermented grains and aged in oak barrels, which give it most of its colour and flavour. Our whiskey compendium is a humble tribute to this great spirit that is made and enjoyed all around the world. “The water was not fit to drink. To make it palatable, we had to add whiskey. By diligent effort, I learned to like it.” - Winston Churchill - OUR COLLECTION 1 – AMERICAN WHISKEY 2 – TRADITIONAL (RYE) BOURBON 3 – WHEATED BOURBON 4 – SMALL BATCH BOURBON 5 – SINGLE BARREL BOURBON 6 – VINTAGE AND UNIQUE BOURBON 7 – TENNESSEE WHISKEY 8 – RYE WHISKEY 9 – OTHER AMERICAN WHISKEY 10 – SCOTCH WHISKY (WHERE IT ALL BEGAN) 11 – BLENDED WHISKY 12 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (SPEYSIDE) 13 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (HIGHLAND & LOWLAND) 14 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (ISLAY & CAMPBELTOWN) 15 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (THE ISLANDS) 16 – INDEPENDENT BOTTLERS 17 – RARE & PRESTIGIOUS 18 – WHISKEYS OF THE WORLD (IRELAND & CANADA) 19 – WHISKIES OF THE WORLD AMERICAN WHISKEY – 1 – A SHORT HISTORY OF WHISKY OR WHISKEY? AMERICAN WHISKEY The Irish and Americans spell American whiskey is regulated by some whiskey with an “e”. The of the strictest laws of any spirit in Scots, Japanese and Canadians the world. Its heritage began when early spell whisky without. American settlers preserved their extra rye crops by distilling them. Although different to the barley they were used to in Europe, rye still made damn good whiskey. It was in the 18th Centu r y, EASY DISTILLATION when a quarter of a million Scottish and Irish immigrants arrived, that Distillation is a way to separate alcohol whiskey became serious business and from water, by boiling fermented grains the tax collectors were, of course, (called mash) and condensing its vapour. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

High Alcohol Products Catalog

HIGH ALCOHOL TURBO YEASTS Make your own spirits and liquers for less than 1/2 price THE ® DIFFERENCE SuperYeast Vodka Pure Moonshiner’s HIGH ALCOHOL Liqueur making is as old as civilization itself. In fact, the recipes and X-Press 135g Yeast w/AG 72g Turbo Pure ® techniques haven’t changed much since the Middle Ages. Carefully w/AG & Citric 112g selected seeds, herbs, fruit and essential oils are macerated or distilled, PRODUCTS CATALOG and then fortified with alcohol and sweetened. Winemakeri Inc. sources the 100% NATURAL EUROPEAN ESSENCES Make your own spirits and liquers for less than 1/2 price best essential oils and extracts from Europe where the ‘old world’ style of extraction is still very much a treasured art. All of our essences are consid- TASTE THE DIFFERENCE ered "Premium Black Label" quality and are gluten-free and sulphite-free. ® Some essences however contain natural nut extracts. Note: Due to the fact that we do not use artificial preservatives in our 100% NATURAL EUROPEAN ESSENCES recipes, some ingredient separation or settling may occur. Refrigerate any TASTE THE DIFFERENCE unused portion of your essence. For best results, use within 2 years from Pot Still Turbo Turbo Pure 24 Hr Turbo purchase. Most of our essences have a shelf life of 5 years or longer under Pure 115g X-Press 175g Pure 200g cool storage. MIXING GUIDE BRANDIES SCHNAPPS ALL liqueur recipes require 25.5 U.S. fl. oz (750 ml) of 15-30% alc./vol GINS T’QUILAS of alcohol. Choose your alcohol base: high proof ethanol (e.g. -

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages

The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages © 2016 Robert A. Freitas Jr. All Rights Reserved. Abstract. Specialized nanofactories will be able to manufacture specific products or classes of products very efficiently and inexpensively. This paper is the first serious scaling study of a nanofactory designed for the manufacture of a specific food product, in this case high-value-per- liter alcoholic beverages. The analysis indicates that a 6-kg desktop appliance called the Fine Spirits Synthesizer, aka. the “Whiskey Machine,” consuming 300 W of power for all atomically precise mechanosynthesis operations, along with a commercially available 59-kg 900 W cryogenic refrigerator, could produce one 750 ml bottle per hour of any fine spirit beverage for which the molecular recipe is precisely known at a manufacturing cost of about $0.36 per bottle, assuming no reduction in the current $0.07/kWh cost for industrial electricity. The appliance’s carbon footprint is a minuscule 0.3 gm CO2 emitted per bottle, more than 1000 times smaller than the 460 gm CO2 per bottle carbon footprint of conventional distillery operations today. The same desktop appliance can intake a tiny physical sample of any fine spirit beverage and produce a complete molecular recipe for that product in ~17 minutes of run time, consuming <25 W of power, at negligible additional cost. Cite as: Robert A. Freitas Jr., “The Whiskey Machine: Nanofactory-Based Replication of Fine Spirits and Other Alcohol-Based Beverages,” IMM Report No. 47, May 2016; http://www.imm.org/Reports/rep047.pdf. 2 Table of Contents 1. -

WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished

WHISK(E)YS BOURBON WHISKEY AMERICAN WHISKEY Angel's Envy Port Barrel Finished ............................................................ $12.00 High West Campfire Whiskey ................................................................... $10.00 Basil Hayden's ............................................................................................ $12.00 Jack Daniel's ............................................................................................... $8.00 Belle Meade Sour Mash Whiskey ............................................................. $10.00 Gentleman Jack ........................................................................................ $11.00 Belle Meade Madeira Cask Bourbon ........................................................ $15.00 George Dickel No.12 ................................................................................... $9.00 Blackened Whiskey .................................................................................... $10.00 Mitcher's American Whiskey .................................................................... $12.00 Buffalo Trace ............................................................................................... $8.00 Mitcher's Sour Mash Whiskey .................................................................. $12.00 Bulleit Bourbon ............................................................................................ $8.00 CANADIAN WHISKY Bulleit Bourbon 10 year old ...................................................................... $13.00 -

The Invicta Whisky Charter from the Distillers of Masthouse Whisky This

The Invicta Whisky Charter from the distillers of Masthouse Whisky This charter is made by Copper Rivet Distillery, England, distillers of Masthouse Whisky. English Whisky stands on the shoulders of the great whiskies from around the world and, as one of the founding distilleries of this revived tradition in England, we are making a commitment to consumers of our spirit that Masthouse Whisky is, and will always be, produced in accordance with these high standards. We do not believe that a tradition of exacting standards, high quality and innovation and experimentation are mutually exclusive. Our home of Chatham’s historic Royal Dockyard has demonstrated this over centuries, crafting and innovating to build world class ships. And we wish to set out areas where we intentionally leave latitude to create new and (or) nuanced expressions of this noble and beloved craft of whisky making. We believe that consumers have a right to know what they are buying and how what they consume and enjoy is produced made. Our commitment is that, when our whisky is chosen, it will have been made in strict adherence with these exacting standards designed to underpin character, flavour and quality. We don’t presume to lay out standards on behalf other great distilleries in other regions of England – we expect that they may wish to set their own rules and standards which underpin the character of their spirit. This is our charter, for our whisky. Our commitment, our promise, our standards – our charter The spirit must be distilled in England, United Kingdom. The entire process from milling grist, creating wort, fermenting distiller’s beer, distillation and filling casks must happen at the same site. -

History of Scotch Whiskey

Scotch Whiskey The Gaelic "usquebaugh", meaning "Water of Life", phonetically became "usky" and then "whisky" in English. However it is known, Scotch whisky, Scotch or Whisky (as opposed to whiskey), it has captivated a global market. Scotland has internationally protected the term "Scotch". For a whisky to be labeled Scotch it has to be produced in Scotland. If it is to be called Scotch, it cannot be produced in England, Wales, Ireland, America or anywhere else. Excellent whiskies are made by similar methods in other countries, notably Japan, but they cannot be called Scotches. They are most often referred to as "whiskey". While they might be splendid whiskies, they do not captivate the tastes of Scotland. "Eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aqua vitae" The entry above appeared in the Exchequer Rolls as long ago as 1494 and appears to be the earliest documented record of distilling in Scotland. This was sufficient to produce almost 1500 bottles, and it becomes clear that distilling was already a well-established practice. Legend would have it that St Patrick introduced distilling to Ireland in the fifth century AD and that the secrets traveled with the Dalriadic Scots when they arrived in Kintyre around AD500. St Patrick acquired the knowledge in Spain and France, countries that might have known the art of distilling at that time. The distilling process was originally applied to perfume, then to wine, and finally adapted to fermented mashes of cereals in countries where grapes were not plentiful. The spirit was universally termed aqua vitae ('water of life') and was commonly made in monasteries, and chiefly used for medicinal purposes, being prescribed for the preservation of health, the prolongation of life, and for the relief of colic, palsy and even smallpox. -

An Important Notice: Due to Covid-19, We Have Temporarily Suspended Cash Payments and Are Currently Taking Card-Only Payments. Credit Card Surcharges Apply

MENU An important notice: Due to Covid-19, we have temporarily suspended cash payments and are currently taking card-only payments. Credit card surcharges apply SPEYSIDE Distilled 30ml. ABERLOUR A’BUNADH - - - - 61% 15 AUCHROISK 7 YEARS by Parkmore selection - - 2010 46% 10 AUCHROISK 11 YEARS 19 month ex-Oloroso Hogshead finish by James Eadie 2008 58.5% 14.5 AULTMORE 12 YEARS Official bottling - - - - 46% 15.5 AULTMORE 11 YEARS Single Hogshead by Blackadder - - 2006 57.6% 19.5 AULTMORE 1987 – 2007 by Scott’s Selection - - 1987 55.8% 37 AULTMORE 23 YEARS Ex-bourbon cask by Maltbarn - - 1997 49.9% 32.5 AULTMORE 14 YEARS by Whisky Galore - - - 1989 46% 39.5 AULTMORE 11 YEARS Bottled by High Spirits “Masters of Magic” - 2008 46% 15.5 THE BALVENIE 12 YEARS DOUBLE WOOD - - - 40% 11.5 THE BALVENIE 14 YEARS CARIBBEAN CASK - - - 43% 13.5 THE BALVENIE 12 YEARS “SWEET TOAST OF AMERICAN OAK” - - 43% 12 THE BALVENIE 14 YEARS “THE WEEK OF PEAT” - - - 48.3% 16 BENRIACH HEART OF SPEYSIDE - - - - 40% 9 BENRIACH 8 YEARS Single sherry butt by Carn Mor - - 2010 46% 11 BENRIACH 10 YEARS ‘Curiositas’ Peated - - - 46% 12 BENRIACH 9 YEARS Ex-Palo Cortado cask by James Eadie - - 2010 62.4% 26 BENRIACH “AUTHENTICUS” 30 YEAR OLD PEATED - - - 46% 68 BENRIACH 23 YEARS Ex-sherry butt by The Whisky Agency - 1997 50.7% 62 BENRINNES 11 YEARS Batch 10 by That Boutique-y whisky company - - 49% 18 BENRINNES 10 YEARS Sherry cask by Adelphi - - 2009 55.9% 21 BENRINNES 11 YEARS ex-Oloroso finish by James Eadie - - 2008 59.9% 27 BENRINNES 11 YEARS 7 month ex-PX Hogshead finish -

International Whisky Competition®

INTERNATIONAL WHISKY COMPETITION™ ENTRY GUIDE Overview…………….…................................ Page 2 Shipping Instructions…................................. Page 3 Category Class Codes.................................. Page 4 2019 IWC Entry Form…............................... Page 5 Golden Barrel Trophy www.WhiskyCompetition.com - [email protected] - Tel: +1-702-234-3602 OVERVIEW Thank you for entering the 10th edition of the International Whisky Competition! Established in 2010, the International Whisky Competition has grown into the most followed whisky competition with over 30,000 fans, one of the most serious and professional whisky competition in the world. Unlike other spirits competitions we only focus on whisk(e)y and we ensure each winner gets the special attention they deserve. What to expect when entering the International Whisky Competition: • Unique medal for each winner featuring the category in which the whisky won. These medals are coveted among master distillers and are recognized by whisky fans to have a significant meaning. • Each winning whisky also receives a superior quality certificate to showcase in your distillery. • Each entry is rated on a 100 point basis and we offer sticker badges for score of over 85 points. We do not publicly disclose the score of anything below 85. • Proper attention given to your whisky as each judge is presented with one whisky at a time. In-depth notes are taken at every step including various aromas and flavours. • Each distillery and the whiskies entered will be listed in the 2020 International Whisky Guide. The Guide features key information about the distillery, its history, contact information, and full aromas and flavours profile for each whisky entered. Because we only list the whiskies present at the competition there are fewer listed and your distillery gets more attention along with a full color picture for each whisky entered. -

A Scotch Whisky Primer

ARDBEG Voted World’s Best Whisky 2008 & 2009 by Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible. This article was originally published online at www.nicks.com.au A Scotch Whisky Primer What is Scotch Whisky? Today, Scotch whisky is one of the world’s leading spirit drinks and also regarded by many as the world’s most ‘noble’ spirit. It is exported to about 200 different markets and frequently outsells every other spirit category. Made from the most elemental of ingredients, water and barley, it has become inextricably woven into the fabric of Scotland’s history, culture and customs. Indeed, there are few products which are so closely related to the land of their birth than ‘Scotch’. For Scots, it is the drink of welcome and of farewell, and much in between. With a dram babies are ushered into the world and guests to the house. In the days when distances were traveled only with difficulty, a jug of whisky was left out for any tradesmen who might call. Business deals were sealed with a dram. All manner of small ailments have been eased with whisky - from children’s teething, to colds and flu. Depart- ing guests were offered a deoch an doruis, the ‘dram at the door’ - in modern terms ‘one for the road’. The dead-departed are remembered and wished Godspeed with large quantities of whisky. As Charles Shields puts it: “...without an appreciation of whisky, I think a visitor to Scotland misses the true beauty of the country; whisky and Scotland are inseparably intertwined.” The word ‘whisky’ originates from the Scots Gaelic word “Uisge Beatha” meaning the ‘water of life’, Anglicised over time to ‘Whiskybae’ until finally being shorten to ‘Whisky’. -

The Highland Herold #23 | Sommer 2014 Fragen Sie Ihren Fachhändler Oder Besuchen Sie Das Internet!

WHIY SK MAGAZIN SOMMER 2014 American Whiskey Kentucky Straight WHIY SKE Bourbon AUS Whiskey AMERIKA D AS LAND, IN DEM 100 Proof BOURBON, RYE UND Tennessee MOONSHINE FLIESSEN Corn Wh SOMMERTAGE Straight Rye GRILLREZEPTE UND ERFRISCHENDE DRINKS Craft Whi Moonshine MORRISON AND MACKAY LTD. Malt Wh NEUE S UNTERNEHMEN Oak Casks AUF DEM SCHOTTICraftSCHEN Distillers WHIskYMARKT Innovation #23 | Sommer 2014 Kostenfrei im Fachhandel Tradition D irektbezug € 2,90 zzgl. Versand www.highland-herold.de New Style WHI SKYFACHHÄNDLER NACH POSTLEITZAHL Bei diesen Fachhändlern gibt es neben Whisk(e)y auch den Highland Herold. Weitere Adressen, unter denen man zwar keinen Highland Herold aber trotzdem viele Whisk(e)ys bekommt, gibt es auf www.highland-herold.de/fachhandel. D ie Schmiede D er Whiskykoch 01445 Radebeul | www.schmiede-radebeul.de 64285 Darmstadt | www.whiskykoch.de Die Genusswelt The Mash Tun 01896 Pulsnitz | www.diegenusswelt-pulsnitz.de 64572 Büttelborn | www.mash-tun.de No. 2 – Die Altstadtkneipe Spahns Scotchwarehouse 04509 Delitzsch | www.whisky-stube.de 64807 Dieburg | www.scotchwarehouse.de Cadenhead’s Whisky Market Berlin Whisky & Dreams 10247 Berlin | www.cadenhead-berlin.de 64859 Eppertshausen | islay-whisky-shop.de Scotland-and-Malts Whisky in Wiesbaden | 65205 Wiesbaden 16225 Eberswalde | www.scotland-and-malts.com www.stores.ebay.de/Whisky-in-Wiesbaden Whiskyland Oranienburg Willi’s Whisky Tasting The Whisky Shop Hartheim 16515 Oranienburg | Stralsunder Straße 4 65428 Rüsselsheim | www.willis-whiskytasting.de 79258 Hartheim | www.the-whisky-shop.de