From Weimar to Nuremberg: a Historical Case Study of Twenty-Two Einsatzgruppen Officers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoah 1 Shoah

Shoah 1 Shoah [1] (« catastrophe » ,שואה : Le terme Shoah (hébreu désigne l'extermination par l'Allemagne nazie des trois quarts des Juifs de l'Europe occupée[2] , soit les deux tiers de la population juive européenne totale et environ 40 % des Juifs du monde, pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale ; ce qui représente entre cinq et six millions de victimes selon les estimations des historiens[3] . Ce génocide des Juifs constituait pour les nazis « la Solution finale à la question juive » (die Endlösung der Judenfrage). Le terme français d’Holocauste est également utilisé et l’a précédé. Le terme « judéocide » est également utilisé par certains pour qualifier la Destruction du ghetto de Varsovie, avril 1943. Shoah. L'extermination des Juifs, cible principale des nazis, fut perpétrée par la faim dans les ghettos de Pologne et d'URSS occupées, par les fusillades massives des unités mobiles de tuerie des Einsatzgruppen sur le front de l'Est (la « Shoah par balles »), au moyen de l'extermination par le travail forcé dans les camps de concentration, dans les « camions à gaz », et dans les chambres à gaz des camps d'extermination. L'horreur de ce « crime de masse »[4] a conduit, après-guerre, à l'élaboration des notions juridiques de « crime contre l'humanité »[5] et de « génocide »[6] , utilisé postérieurement dans d'autres contextes (génocide arménien, génocide des Tutsi, etc.). Une très grave lacune du droit international humanitaire a également été complétée avec l'adoption des Conventions de Genève de 1949, qui protègent la population civile en temps de guerre[7] . L'extermination des Juifs durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale se distingue par son caractère industriel, bureaucratique et systématique qui la rend unique dans l'histoire de l'humanité[8] . -

Die Deutsche Ordnungspoli2ei Und Der Holocaust Im Baltikum Und in Weissrussland 1941-1944

WOLFGANG CURILLA DIE DEUTSCHE ORDNUNGSPOLI2EI UND DER HOLOCAUST IM BALTIKUM UND IN WEISSRUSSLAND 1941-1944 2., durchgesehene Auflage FERDINAND SCHONINGH Paderborn • Munchen • Wien • Zurich INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Vorwort 11 Einleitung 13 ERSTER TEIL: GRUNDLAGEN UND VORAUSSETZUNGEN .... 23 1. Entrechtung der Juden 25 2. Ordnungspolizei 49 3. Die Vorbereitung des Angriffs auf die Sowjetunion 61 4. Der Auftrag an die Einsatzgruppen 86 ZWEITER TEIL: DIE TATEN 125 ERSTER ABSCHNITT: SCHWERPUNKT BALTIKUM 127 5. Staatliche Polizeidirektion Memel und Kommando der Schutzpolizei Memel 136 6. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 11 150 7. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 65 182 8. Schutzpolizei-Dienstabteilung Libau 191 9. Polizeibataillon 105 200 10. Reserve-Polizei-Kompanie z.b.V. Riga 204 11. Kommandeur der Schutzpolizei Riga 214 12. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 22 244 13. Andere Polizeibataillone 262 I. Polizeibataillon 319 262 II. Polizeibataillon 321 263 III. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 53 264 ZWEITER ABSCHNITT: RESERVE-POLIZEIBATAILLONE 9 UND 3 - SCHWERPUNKT BALTIKUM 268 14. Einsatzgruppe A/BdS Ostland 274 15. Einsatzkommando 2/KdS Lettland 286 16. Einsatzkommando 3/KdS Litauen 305 DRITTER ABSCHNITT: SCHUTZPOLIZEI, GENDARMERIE UND KOMMANDOSTELLEN 331 17. Schutzpolizei 331 18. Polizeikommando Waldenburg 342 g Inhaltsverzeichnis 19. Gendarmerie 349 20. Befehlshaber der Ordnungspolizei Ostland 389 21. Kommandeur der Ordnungspolizei Lettland 392 22. Kommandeur der Ordnungspolizei Weifiruthenien 398 VLERTER ABSCHNITT: RESERVE-POLIZEIBATAILLONE 9 UND 3 - SCHWERPUNKT WEISSRUSSLAND 403 23. Einsatzkommando 9 410 24. Einsatzkommando 8 426 25. Einsatzgruppe B 461 26. KdS WeiSruthenien/BdS Rufiland-Mitte und Weifiruthenien 476 F0NFTER ABSCHNITT: SCHWERPUNKT WEISSRUSSLAND 503 27. Polizeibataillon 309 508 28. Polizeibataillon 316 527 29. Polizeibataillon 322 545 30. Polizeibataillon 307 569 31. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 13 587 32. Reserve-Polizeibataillon 131 606 33. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland

Miranda Walston Witnessing Extermination: Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland Honours Thesis By: Miranda Walston Supervisor: Dr. Lauren Rossi 1 Miranda Walston Introduction The Holocaust spanned multiple years and states, occurring in both German-occupied countries and those of their collaborators. But in no one state were the actions of the Holocaust felt more intensely than in Poland. It was in Poland that the Nazis constructed and ran their four death camps– Treblinka, Sobibor, Chelmno, and Belzec – and created combination camps that both concentrated people for labour, and exterminated them – Auschwitz and Majdanek.1 Chelmno was the first of the death camps, established in 1941, while Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec were created during Operation Reinhard in 1942.2 In Poland, the Nazis concentrated many of the Jews from countries they had conquered during the war. As the major killing centers of the “Final Solution” were located within Poland, when did people in Poland become aware of the level of death and destruction perpetrated by the Nazi regime? While scholars have attributed dates to the “Final Solution,” predominantly starting in 1942, when did the people of Poland notice the shift in the treatment of Jews from relocation towards physical elimination using gas chambers? Or did they remain unaware of such events? To answer these questions, I have researched the writings of various people who were in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” I am specifically addressing the information found in diaries and memoirs. Given language barriers, this thesis will focus only on diaries and memoirs that were written in English or later translated and published in English.3 This thesis addresses twenty diaries and memoirs from people who were living in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” Most of these diaries (fifteen of twenty) were written by members of the intelligentsia. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The Holocaust Perpetrators

CLARK UNIVERSITY HIST / HGS 237 / 337 The Holocaust Perpetrators Spring 2017 Professor Thomas Kühne Time: Monday, 2:50-5:50 pm, Place: Strassler Center/Cohen-Lasry House Office Hours: Tuesday, 1-2 pm, Strassler Center 2nd fl, and by appointment Phone: (508) 793-7523, email: [email protected] Killing of Soviet Civilians in the Ukraine, fall 1941 1 Images of Adolf Eichmann: rabbit farmer in Argentina, 1954; “Anthropomorphic Depiction” by (Holocaust survivor) Adolf Frankl, 1957. 2 3 Description This course explores how, and why, Germans and other Europeans committed the Holocaust. It examines the whole range of different groups and types of perpetrators. We will be looking at desktop perpetrators such as Adolf Eichmann, at medical doctors who used Jews for their inhuman experiments, at the concentration camp guards, and at the death squads (Einsatzgruppen) as the hard core of the SS elite. Furthermore, we will investigate the actions, ideologies, and emotions of “ordinary” Germans who served in police battalions and in the drafted army, of women who served as camp guards and in the occupational regime, and of non-German collaborators. The course investigates the interrelation of motivations and biographies, of emotional attitudes and ideological orientations, and of social and institutional arrangements to answer why “normal” humans became mass murderers. Requirements This course will be taught in the spirit of a tutorial: once you decided to take the class, you are expected to stick to it, come to the sessions and be well prepared. To facilitate informed discussion, you are required to write a short paper of no more than one page (half of a page will usually do it) for each session, related the assigned books and essays. -

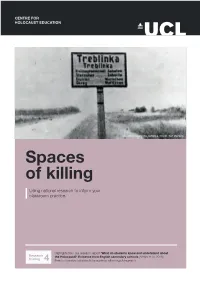

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Criminals with Doctorates: an SS Officer in the Killing Fields of Russia

1 Criminals with Doctorates An SS Officer in the Killing Fields of Russia, as Told by the Novelist Jonathan Littell Henry A. Lea University of Massachusetts-Amherst Lecture Delivered at the University of Vermont November 18, 2009 This is a report about the Holocaust novel The Kindly Ones which deals with events that were the subject of a war crimes trial in Nuremberg. By coincidence I was one of the courtroom interpreters at that trial; several defendants whose testimony I translated appear as major characters in Mr. Littell's novel. This is as much a personal report as an historical one. The purpose of this paper is to call attention to the murders committed by Nazi units in Russia in World War II. These crimes remain largely unknown to the general public. My reasons for combining a discussion of the actual trial with a critique of the novel are twofold: to highlight a work that, as far as I know, is the first extensive literary treatment of these events published in the West and to compare the author's account with what I witnessed at the trial. In the spring of 1947, an article in a Philadelphia newspaper reported that translators were needed at the Nuremberg Trials. I applied successfully and soon found myself in Nuremberg translating documents that were needed for the ongoing cases. After 2 passing a test for courtroom interpreters I was assigned to the so-called Einsatzgruppen Case. Einsatzgruppen is a jargon word denoting special task forces that were sent to Russia to kill Jews, Gypsies, so-called Asiatics, Communist officials and some mental patients. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38002-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-38002-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. ont ete enleves de cette these. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz's

“Are you going to help me save the world?” From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz’s Lifelong Stand for “Law. Not War.” Creed King and Kate Powell Senior Division Group Exhibit Student-composed Words: 493 Process Paper: 500 words Process Paper Who took a stand for the Jews after World War II? Pondering this compelling question, we stumbled upon the story of Benjamin Ferencz. As a young lawyer, Ferencz convinced fellow attorneys at the Nuremberg Trials to prosecute the Einsatzgruppen, Hitler’s roving extermination squads, in the “biggest murder trial of the century” (Tusa). Ferencz convicted all twenty-two defendants, then parlayed his Nuremberg experience into a lifelong stand for world peace through the application of law. Our discovery that Ferencz, at age ninety-seven, is the last living Nuremberg prosecutor – and living in our home state – led to a remarkable interview. We began by researching primary sources such as oral histories and evidence gathered after the war by the War Crimes Branch of the US Army and compared these to personal accounts archived by the Florida State University Institute on World War II. Reading memos and logbooks kept by the Nazis helped us understand the significance of Ferencz’s stand at Nuremberg. Ferencz’s papers provided interviews, photographs, and documents to corroborate historical data and underscore his lifelong advocacy for peace. For a firsthand perspective, we conducted several personal interviews. Talking with Ferencz about his transformation from prosecutor to modern activist for world peace and Zelda Fuksman on surviving the Holocaust and her perspective on the Nuremberg Trials were two crucial pieces of research.