South Houston Industrial Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 of 1 Forecast of Contracts to Be Advertised and Proposals to Be Solicited

Welcome to the latest MTA "Eye on the Future," in which we present currently funded capital projects that are planned to be advertised from September 2017 through August 2018. The "Eye" is hosted along with other information and resources about the MTA Capital Program in one convenient location. It is part of our commitment to improve business practices and we hope that it is useful to you. The MTA Capital Program is very important for the safety and reliability of the MTA transportation system and is vital for the regional economy. As described in this issue of the "Eye," the MTA is preparing to undertake 145 projects valued at approximately $4.71 billion in capital work. This work spans many areas, including civil, structural, and electrical, as well as new technologies. These projects are crucial for the reliability, growth and resiliency of the system and contribute to the regional economy. This amount of investment is projected to generate approximately $8.29 billion in economic activity for the New York region. We want to make sure you’re aware of our recently-launched web-portal: MyMTA.info. This portal enables suppliers and bidders to the MTA to search procurement opportunities and information across all MTA agencies, respond to sourcing events online, select categories for the goods and services your sell and more. Contractors and suppliers have a critical stake in the success of the Capital Program. We appreciate your interest in and support of the projects included in this issue of the "Eye," and we look forward to your participation. -

April 2004 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - APRIL, 2004 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 47, No. 4 April, 2004 The Bulletin NYC TRANSIT’S REHABILITATION PROGRAM Published by the New While surfing the Internet, our Production ADA ACCESSIBILITY — JUNCTION BOULEVARD York Division, Electric Manager found a list of proposed new con- STATION: Three ADA compliant elevators will Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box tracts. The following are of interest to our be installed at the Junction Boulevard station 3001, New York, New readers: on the Flushing Line. Platform edge modifica- York 10008-3001. NEW SOUTH FERRY TERMINAL: NYC Transit tions and warning strips will be provided. would like to build a new station to replace ADA-required signage and an automated For general inquiries, the century-old South Ferry station, which fare access system will be installed. ST contact us at was opened on July 10, 1905. This station ADA ACCESSIBILITY — 231 STREET STA- [email protected] or by cannot accommodate a full-length train and TION: NYC Transit would like to install two phone at (212) 986-4482 is located on a sharp curve. NYC Transit ex- ADA-compliant elevators from the street to (voice mail available). ERA’s website is pects to build a new tunnel diverging from the the northbound and southbound control st www.electricrailroaders. existing tunnel at Greenwich Street and Bat- houses at the 231 Street station of the org. tery Place and continuing under Battery Park Broadway-Seventh Avenue Line. The con- to a new station under Peter Minuit Plaza. A tractor will reduce the gap between the plat- Editorial Staff: new mezzanine with direct access to the form edge and the door sill and provide plat- Editor-in-Chief: south mezzanine of the Whitehall Street sta- form edge warning strips and ADA- Bernard Linder tion would be built above the proposed new accessible turnstiles. -

Philosophical Foundations of Health Education

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF HEALTH EDUCATION BL ACK FURNEY Philosophical Foundations of Health Education covers the philosophical and ethical foundations of the practice of health education in school, community, work site, and GRAF hospital settings, as well as in health promotion consultant activities. The book presents NOLTE personal philosophies of health educators, essential philosophical perspectives, and a range of philosophical issues that are relevant to health education practice. Philosophical PHILOSOPHICAL Foundations of Health Education is organized around the fi ve major philosophical traditions: cognitive-based, decision-making, behavior change, freeing/functioning, and social change. Co-published with the American Association for Health Education, this important work is an essential resource for student and professional. Each section contains a challenge to the reader that suggests critical thinking questions to reinforce the key points of the chapter, EDUCATION HEALTH FOUNDATIONS invite comparison with other perspectives, refl ect on the implications of the perspective, note themes that run through the chapters, and consider practical applications of the OF FOUNDATIONS PHILOSOPHICAL various philosophical approaches. The Editors OF Jill M. Black, PhD, CHES, is an associate professor in the Department of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance at Cleveland State University and coordinator of the Community Health Education Program. She is a fellow of the American Association for Health Education. Steven R. Furney, EdD, MPH, is a professor of Health Education and director of the Division of Health Education at Texas State University. He is a fellow of the American Association for HEALTH Health Education. Helen M. Graf, PhD, is an associate professor and undergraduate program director in the Department of Health and Kinesiology at Georgia Southern University. -

PAUL Mccartney Auf Neuem CLAPTON-Album

Montag, 22. April 2013 Auch telefonische Info und Bestellung ist möglich: Di. - So. tagsüber Ab 50,00 Euro Bestellwert übernehmen wir die Portokosten. 22. April - IT WAS MANY YEARS AGO TODAY: Dienstag, 22. April 1969: Namensänderung von JOHN WINSTON LENNON in JOHN WINSTON ONO LENNON auf Apple-Haus-Dach. Freitag, 22. April 1977: BEATLES-LP LIVE AT THE STAR CLUB IN HAMBURG, GERMANY 1962 in West-Deutschland. Freitag, 22. April 1977: PERCY „THRILLS“ THRILLINGTON alias PAUL McCARTNEY-Single UNCLE ALBERT-ADMIRAL HALSEY in England. Dienstag, 22. April 2003: RINGO STARR-Album RINGO RAMA in Europa und USA. Hallo M.B.M., hallo BEATLES-Fan! PAUL McCARTNEY auf neuem CLAPTON-Album: Dienstag, 12. März 2013: Doppel-LP (180 Gramm) mit Download Card OLD SOCK. 29,90 € Brushbranch Records (Produktion) und Surfdog Records (Vertrieb) 1-18016, USA. Freitag, 22. März 2013: CD OLD SOCK. 15,90 € Universal Records 3733098, Europa. LP 1, Seite 1: CD: Track 1: Eric Clapton: Further On Down The Road. Track 2: Eric Clapton & J. J. Cale: Angel. Track 3: Eric Clapton: The Folks Who Live On The Hill. LP 1, Seite 2: CD (Fortsetzung): Track 4: Eric Clapton & Chaka Khan: Gotta Get Over. Track 5: Eric Clapton: Till Your Well Runs Dry. Track 6: ERIC CLAPTON & PAUL McCARTNEY (Gesang, Bassgitarre): All Of Me (3:22). LP 2, Seite 1: CD (Fortsetzung): Track 7: Eric Clapton: Born To Lose. Track 8: Eric Clapton & Steve Winwood: Still Got The Blues. Track 9: Eric Clapton: Goodnight Irene. LP 2, Seite 2: CD (Fortsetzung): Track 10: Eric Clapton: Your One and Only Man. -

O July 28 We Banjo 3 (Tickets) O July 29 Roosevelt Dime (Tickets) O July

o July 28 We Banjo 3 (Tickets) o July 29 Roosevelt Dime (Tickets) o July 30 Boudreaux’s Back Porch (Tickets) o July 31 Tribute to the Everly Brothers with Ryan Humbert & Emily Bates (Tickets) o August 1 Summer Soul Concert (Tickets) o August 1 Blue Lunch (Tickets) o August 2 Rooftop view, Brew, BBQ (Tickets) o August 2 Karaoke Night (Tickets) o August 3 Parachute (Tickets) o August 5 The Thor Platter Band (Tickets) o August 6 The Black Lillies (Tickets) o August 7 Rooftop Dinner Party ~ Farm to Table (Tickets) o August 7 Sinatra Night (Tickets) o August 8 Honeybucket (Tickets) o August 8 Whiskey River Revival Hosted by Hillbilly Idol (Tickets) o August 9 Ahi-Nama (Tickets) o August 12 Harpeth Rising (Tickets) o August 13 The HillBenders Present: Tommy (Tickets) o August 13 Rooftop Wine Tasting (Tickets) o August 14 Adron (Tickets) o August 14 Travis Haddix (Tickets) o August 15 Tropical Cleveland Noch Tropical (Tickets) o August 15 Thornetta Davis (Tickets) o August 16 Tracy and the Tuxedos (Tickets) o August 19 Vicki Chew (Tickets) o August 20 Nikki Hill (Tickets) o August 20 Rasputina (Tickets) o August 21 Miss Alexandra Huntingdon and the Gentlemen’s Intermission (Tickets) o August 26 Hot Djang! (Tickets) o August 27 Jimmy Thackery (Tickets) o August 28 Slowhand: A Tribute to Eric Clapton (Tickets) o August 28 Rachel and the Beatnik Playboys (Tickets) o August 29 Bossa Nova Night with Luca Mundaca (Tickets) o August 29 Old No. 55 (Tickets) o August 30 The Way Down Wanderers (Tickets) o September 3 Motown Night with Nitebridge (Tickets) -

The Book Collection at the Veggie Center FAR from COMPLETE, THIS LIBRARY of VEGETARIAN SOURCES SHOWS the BREADTH of OUR CULTURE

2 WHAT YOU’LL FIND AT THE VEGETARIAN CENTER OF NYC: A RESOURCE GUIDE The Vegetarian Center is the If you’re a vegetarian, we’ve brightest jewel in VivaVegie’s got the answers! education and outreach crown. The Vegetarian Center of NYC is a unique clearinghouse for information. On a daily basis, it receives numerous The VivaVegie Society has a solid history of service to phone calls and walk-in visits from inquisitive people in- the vegetarian community. Since 1991 it has distributed terested in the vegetarian lifestyle. People are always tens of thousands of copies of its hallmark publication, grateful for what the center has to offer them, usually “101 Reasons Why I’m a Vegetarian” by Pamela free of charge. Rice. It has continuously published its journal, The Viva- Vine, for over 10 years. It has been tireless in its dedication This place is here for you. to creative and effective vegetarian street outreach. Hun- Today we vegetarians have a place to call home—a fa- dreds of people, and perhaps thousands, have adopted cility that is there strictly on our behalf. In the long run, the vegetarian lifestyle because of the efforts of the group. the center will grow into whatever the vegetarian com- VivaVegie’s proudest accomplishment, however, has munity of New York City decides it should be. VivaVegie been the opening of its Vegetarian Center. Here is a has laid a foundation. The challenge for us as a com- place that focuses on projecting the vegetarian point of munity is to come together and build this center into a view as its primary mission. -

Catafid2010.Pdf

LES VARIÉTÉS partenaire de la 21e édition du FIDMARSEILLE 5 salles classées art & essai / recherche | café - espace expositions 37, rue Vincent Scotto - Marseille 1er | tél. : 04 91 53 27 82 Sommaire / Contents PARTENAIRES / PARTNERS & SPONSORS 005 ÉDITORIAUX / EDITORIALS 006 PRIX / PRIZES 030 JURYS / JURIES 033 Jury de la compétition internationale / International competition jury 034 Jury de la compétition française / French competition jury 040 Jury GNCR, jury Marseille Espérance, jury des Médiathèques GNCR jury, Marseille Espérance jury and Public libraries jury 046 SÉLECTION OFFICIELLE / OFFICIAL SELECTION 047 Éditorial / Editorial 048 Film d’ouverture / Opening film 052 Compétition internationale / International competition 053 Compétition premier / First film competition 074 Compétition française / French competition 101 ÉCRANS PARALLÈLES / PARALLEL SCREENS 117 Rétrospective Ritwik Ghatak 119 Anthropofolies 125 Du rideau à l’écran 157 Paroles et musique 177 Les sentiers 189 SÉANCES SPÉCIALES / SPECIAL SCREENS 221 TABLES RONDES - RENCONTRES / ROUND TABLES - MASTER CLASSES 231 FIDMarseille AVEC / FIDMarseille WITH 235 VIDÉOTHÈQUE / VIDEO LIBRARY 241 FIDLab 251 ÉQUIPE, REMERCIEMENTS, INDEX TEAM, ACKNOWLEGMENTS, INDEXES 255 C.A. et équipe FIDMarseille / FIDMarseille management committee and staff 256 Remerciements / Thanks to 257 Index des films / Film index 258 Index des réalisateurs / Filmmaker index 260 Index des contacts / Contact index 261 Partenaires / Partners & sponsors Le Festival International du Documentaire de Marseille -

“…Standing by the Crossroads…” Seven Signature Tones from Eric Clapton

“…standing by the crossroads…” Seven signature tones from Eric Clapton. C R O S S R O A D S ™ • L I M I T E D E D I T I O N Crossroads™ A “Sunshine of Your Lo e” R From v to T A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this pedal is being “Layla Unplugged”…seven signature I donated to Crossroads Centre, an International Centre S of Excellence for the treatment of alcohol, drugs and tones from Eric Clapton in a limited- T other addictive disorders. ® edition DigiTech effects pedal. S E R “Badge” “Layla” n conjunction with Eric Clapton, I Goodbye Layla and Other we have helped recreate some of his E I Assorted Love Songs S “Crossroads” classic tones in a DigiTech pedal by Wheels of “Lay Down Sally” applying our new Production Modeling™ E Fire, Li e at Slowhand v ™ F the Fillmore “Layla” technology to create Crossroads. F “Sunshine of Unplugged, LIVE For the fi rst time, complex studio E Your Love” C and live effects can be accurately Disraeli Gears “Reptile” T Reptile reproduced thanks to Production S Modeling via our AudioDNA® DSP P super-chip. If you’re a Slowhand fan E D or just want to add some unique tones Crossroads™ 7 New DigiTech Production Modeling™ A technology accurately recreates seven signature Eric Clapton tones. to your effects palette, demo the L 7 Legendary “woman tone” 7 Raw “Crossroads” blues captured live limited edition Crossroads pedal 7 Embracing stereo spectrum of a swirling Leslie™ 7 Intimacy of Unplugged 7 Enduring warmth of “Reptile” 7 Custom artist at your DigiTech dealer today. -

Here’S One in Every Crowd Erlasting Cultural Statement – Everything You Do from a Lot

Hittin’ the Note: Bill, did you feel at all a need to vindicate this period of Clapton’s music? Once you’ve It’s OK; you’re safe with me! photo by Sid Smith been labeled “God” – as Clapton was in what began as graffi ti on a London subway wall and grew into an ev- Well, I actually happen to like There’s One in Every Crowd erlasting cultural statement – everything you do from a lot. I understand why it’s overlooked – there’s no big hit that moment is viewed under a microscope. It seems, on there, and the cover was probably not the most striking. I though, that this particular chapter of Eric’s story has think most people don’t realize the business of the business taken some critical heat over the years. – There’s One In Every Crowd and E.C. Was Here were cut out in 1976 because RSO Records left Atlantic and went to Bill Levenson: I think what I came up against right from Polydor. There was a housecleaning of product, and when the start wasn’t a vindication of the music or the artist − it those records got cut out, they didn’t come into print again was the vindication of the There’s One In Every Crowd and for a decade. People think that they were cut out because E.C. Was Here albums. When people talk about this era, they weren’t good or they weren’t selling, but they were cut they invariably talk about 461 Ocean Boulevard – it was out because distribution stopped on the Atlantic side. -

Wonderful Tonight Chords by Eric Clapton Tabs @ Ultimate Guitar Archive 09-12-20 16:04

Wonderful Tonight Chords by Eric Clapton tabs @ Ultimate Guitar Archive 09-12-20 16:04 Wonderful Tonight Chords by Eric Clapton + --------------------------------------------------------------------- + | Ultimate Guitar Tabs Archive - your #1 source for tabs! | | http://www.ultimate-guitar.com/ | | | | Over 300,000 guitar, guitar pro and bass tabs! Also lessons, news, | | columns and guitar forums! | + --------------------------------------------------------------------- + Artist: Eric Clapton Song: Wonderful Tonight Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton from the album "Slowhand" The Solo/intro goes like this s=slide r=ring b=bend e-7s-5s-3s-5r--7s-5s-3-0r--7s-5s-3s-5s-7s-8s-12s-10b you'll have to listen to the song to get the timing write but, enjoy! any q's or comments, send em to [email protected] enjoy! joe... G D/F# C D G D/F# C D G D/F# It's late in the evening C D She's wondering what clothes to wear G D/F# She puts on her make up C D And brushes her long blonde hair C D And then she asks me G Bm/F# Em Do I look alright C D G D/F# C D And I say yes, you look wonderful tonight G D/F# We go a party C D And everyone turns to see G D/F# This beautiful lady C D That's walking around with me C D And then she asks me G Bm/F# Em Do you feel alright C D G And I say yes, I feel wonderful tonight C http://www.ultimate-guitar.com/print.php/id39629/?transpose=0 Page 1 sur 3 Wonderful Tonight Chords by Eric Clapton tabs @ Ultimate Guitar Archive 09-12-20 16:04 I feel wonderful D G Bm/F# Em Because I see the love light in your eyes C D And -

World View Pages (Page 1)

FALL 1998 | ISSUE #15 As a nonprofit, totally independent magazine, Stay Free! depends on your support. PLEASE SUBSCRIBE. 3 issues are $10 from P.O. Box 306 Prince Street Station, New York, NY 10012. (Canada & Mexico: $11; C. & S. America, Europe: $15; Elsewhere: $17) Another season, another issue, and an local stunts and pranks. If you’re in New acedote: A young man interning where I York, reliable, and interested in this sort of work recently introduced himself as a huge thing, feel free to get in touch. It would also fan of Stay Free! We chatted and he elabo- be great to have some help with the rated. He is majoring in marketing, has long magazine itself. been fascinated with advertising, and hopes Since the last issue, I’ve started writing some day to make really cool ads. about advertising for the Village Voice. Four Not exactly the hoped-for response. articles here were originally published there. Sure, readers take what they will. No point The back cover this issue breaks house getting uptight about that or trying to shove rules against hassling people about what something down throats (not that I haven’t they buy. Forgive us. Sport utility vehicles tried). But it does give one pause. (For the must be stopped! record, Stay Free!’s policy on what to major in is as follows: Find out which department Carrie McLaren at your school has the best teachers—ask Fall/Winter 1998 around—and then major in that.) I got a call the other day from Tommy Hilfiger’s publicist offering me a chance to go ride in Tommy’s plane or ship (it was a vehicle) if I wrote about it. -

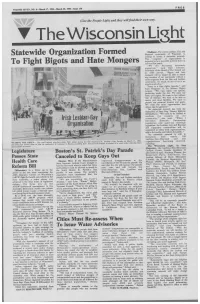

View Full Issue As

VOLUME SEVEN, NO. 6—March 17, 1994—March 30, 1994—Issue 150 FREE Give the People Light and they will find their own way. IV The Wisconsin Light Statewide Organization Formed [Madison]- The entire Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual community of Wisconsin is uniting to create a statewide network. This "congress" of organizations is To Fight Bigots and Hate Mongers expected to be a powerful political force in the next few years. "We are becoming extremely organized," said Dale Johnson, President of the Board of The United and an AIDS activist. "Bigots and hate mongers will no longer be able to attack any member of our community without a swift response from the Gay and Lesbian community. An attack on one of us is an attack on all of us." There is a Gay rights agenda," said Karl Hoagland of the Human Rights League. "We want equal, not special, protection under the law. We want our basic civil rights. We want to live without fear of violence. We want to be able to marry and raise families. We want to pursue our personal dreams and goals. We want the same opportunities that others take for granted." The statewide network has been the brainchild of State Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Madison). "We need to be unified to confront the assaults on our community," she said. "When I introduce Domestic Partnership legislation and same-sex marriage legislation, the Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual and supportive communities will be organized to lobby their representatives, talk to the media, and inform the public." The statewide network is still in formation with nearly 100 Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual and ally WEARING THE GREEN— marchers Gay and Lesbian make their debut during the San Francisco St.