Defining the Right of Self-Defense: Working Toward the Use of a Deadly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrick to Assume 2Nd AF Command Brig

A PUBLICATION OF THE 502nd AIR BASE WING – JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO LACKLAND AIR FORCE BASE, TEXAS • www.lackland.af.mil • V ol. 68 No. 25 • JUNE 24, 2011 NETWORKING INSIDE Commentary 2 Recognition 6 What’s Happening 22 News & Features Offi cer promotions 10 Bidding adieu 14 Photo by Robbin Cresswell Airman Eduardo Guerrero, 802nd Communications Squadron, works on Brocade Switch fi ber in Bldg. 1050 on June 16. The 802nd CS manages com- munications, information management, and visual imaging systems on Lackland. Operation Air Force 15 Patrick to assume 2nd AF command Brig. Gen. Leonard A. Patrick, command- aspects of nearly 2,500 Wing at Goodfellow AFB, er, 502nd Air Base Wing/Joint Base San An- active training courses Texas, the 37th Training tonio, has been selected as commander, Sec- taught to approximately Wing at Lackland AFB ond Air Force, Air Education and Training 245,000 students annu- and the 82nd Training Command, Keesler Air Force Base, Miss. ally in technical training, Wing at Sheppard AFB, Summer fun 24 In this new position, General Patrick will basic military training, Texas; and the 381st be responsible for the development, over- initial skills training, ad- Training Group located sight and direction of all operational aspects vanced technical train- at Vandenberg AFB, of basic military training, initial skills train- ing and distance learn- Calif.; and a network of ing and advanced technical training for the ing courses. 92 fi eld training units Air Force enlisted force and support offi cers. Training operations around the world. The He has held his present position since July across Second Air Force 37th TRW also oversees 2009. -

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA BOO KK Class 2020-2 27

BBIIOOGGRRAAPPHHIICCAALL DDAATTAA BBOOOOKK Class 2020-2 27 Jan - 28 Feb 2020 National Defense University NDU PRESIDENT Vice Admiral Fritz Roegge, USN 16th President Vice Admiral Fritz Roegge is an honors graduate of the University of Minnesota with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering and was commissioned through the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program. He earned a Master of Science in Engineering Management from the Catholic University of America and a Master of Arts with highest distinction in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College. He was a fellow of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Seminar XXI program. VADM Fritz Roegge, NDU President (Photo His sea tours include USS Whale (SSN 638), USS by NDU AV) Florida (SSBN 728) (Blue), USS Key West (SSN 722) and command of USS Connecticut (SSN 22). His major command tour was as commodore of Submarine Squadron 22 with additional duty as commanding officer, Naval Support Activity La Maddalena, Italy. Ashore, he has served on the staffs of both the Atlantic and the Pacific Submarine Force commanders, on the staff of the director of Naval Nuclear Propulsion, on the Navy staff in the Assessments Division (N81) and the Military Personnel Plans and Policy Division (N13), in the Secretary of the Navy's Office of Legislative Affairs at the U. S, House of Representatives, as the head of the Submarine and Nuclear Power Distribution Division (PERS 42) at the Navy Personnel Command, and as an assistant deputy director on the Joint Staff in both the Strategy and Policy (J5) and the Regional Operations (J33) Directorates. -

United States Air Force Ground Accident Investigation Board Report

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE GROUND ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION BOARD REPORT 81st Aerospace Medicine Squadron 81st Training Wing Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi TYPE OF ACCIDENT: Fitness Assessment Fatality LOCATION: Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi DATE OF ACCIDENT: 20 August 2018 BOARD PRESIDENT: Colonel David J. Duval, USAF Conducted IAW Air Force Instruction 51-307 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE GROUND ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION Fitness Assessment Fatality Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi 20 August 2018 On 20 August 2018, at approximately 0740 hours local time, Mishap Airman (MA), a 29-year old Air Force First Lieutenant assigned to the 81st Aerospace Medicine Squadron, Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi, collapsed during the final lap of the 1.5 mile run during an Air Force Fitness Assessment on Keesler Air Force Base’s outdoor Triangle Track. When Fitness Assessment Cell (FAC) members came to the aid of MA, he was responsive and answered questions, but had difficulty breathing and complained of back and leg pain. Shortly after the FAC members contacted emergency services, MA became confused and combative. Within minutes, emergency responders from the Keesler Air Force Base Fire Department arrived on scene, followed quickly by an 81st Medical Group ambulance crew. Emergency responders rapidly moved MA to the ambulance and transported him to the 81st Medical Group Emergency Department. Medical staff diagnosed severe exertional overheating and muscle breakdown (rhabdomyolysis). The staff established that MA had a previous diagnosis of sickle cell trait. Upon MA’s arrival, his heart began beating erratically and was not providing enough oxygen to his body. Medical staff restored normal heart function, and when MA was stable, they transferred him to the intensive care unit. -

Keesler Air Force Base in 2011, the City of Biloxi Joined Keesler Air Force Base in Celebrating the Base’S 70Th Anniversary

Keesler Air Force Base www.keesler.af.mil In 2011, the City of Biloxi joined Keesler Air Force Base in celebrating the base’s 70th anniversary. In 1941, the City deeded 1,563 acres to the War Department, which activated the land as a U.S. Army Air Corps technical training center just a few months before the U.S. entered World War II. Since its activation, more than 2.2 million students have been trained at Keesler, with an average daily student load of over 4,000. According to its FY2010 Economic Impact Report, Keesler employed about 8,200 military personnel and approximately 4,000 civilian workers. The host training unit, the 81st Training Wing, is the electronics training Center of Excellence for the U.S. Air Force. The unit hosts the 2nd Air Force, the 403rd Wing (Hurricane Hunters) as well as the 2nd largest Air Force medical treatment facility in the U.S., Keesler Medical Center. 81st Training Wing The 81st Training Wing at Keesler is one of the Air Force’s largest technical training groups, providing training for the Air Force, Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard and other military • An estimated 160,000 people and civilian federal agency personnel in computer and communications systems, electronics, air attended Keesler’s Open House traffic control, weather, personnel, finance and force support. The 81st also provides advanced and Air Show, Angels Over the training for C-21 pilots. Bay, in March 2011. The Navy As home to the Air Force’s new cyber schoolhouse, in which officers and enlisted students are trained in new cyber operations specialties, Keesler is implementing 19 new cyber courses Blue Angels and Army Golden replacing 13 previous communications courses. -

224 Lives $11.6 Billion 186 Aircraft

MILITARY AVIATION LOSSES FY2013–2020 4 22 Lives $11.6 billion 186 aircraft ON MIL ON ITA SI RY IS A V M I M A T O I O C N L National Commission on A S A N F O E I T T A Y N NCMAS Military Aviation Safety Report to the President and the Congress of the United States DECEMBER 1, 2020 ON MIL ON ITA SI RY IS A V M I M A T O I O C N L A S A N F O E I T T A Y N NCMAS National Commission on Military Aviation Safety Report to the President and the Congress of the United States DECEMBER 1, 2020 Cover image: U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptors from the 199th Fighter Squadron Hawaii Air National Guard and the 19th Fighter Squadron at Joint Base Pearl Harbor- Hickam perform the missing man formation in honor of fallen servicemembers during a Pearl Harbor Day remembrance ceremony. The missing man formation comprises four aircraft in a V-shape formation. The aircraft in the ring finger position pulls up and leaves the formation to signify a lost comrade in arms. (Department of Defense photo by U.S. Air Force Tech. Sgt. Michael R. Holzworth.) ON MIL ON ITA SI RY IS A V M I M A T O I O C N L A S A N F O E I T T A Y N NCMAS The National Commission on Military Aviation Safety dedicates its work to the men and women who serve in the aviation units of the U.S. -

Keesler Senior Enlisted Advisor's

CONTENTS Second Lieutenant Samuel Reeves Keesler, Jr. 2 History of Keesler Air Force Base 4 History of the 81st Training Wing 25 Keesler Host Unit Commander’s 28 81st Wing Commander’s 29 Keesler Senior Enlisted Advisor’s/Command Chief Master Sergeant’s 31 Lineage and Honors 32 Aircraft Assigned 33 Chronology 34 Second Lieutenant Samuel Reeves Keesler, Jr. 1896 - 1918 Samuel Reeves Keesler, Jr., was born in Greenwood, Mississippi on 11 April 1896. He was an outstanding student leader and athlete in high school and at Davidson College in North Carolina. Keesler entered the U.S. Army Air Service on 13 May 1917. He was commissioned a second lieutenant on 15 August, and received training as an aerial observer at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, before sailing to France in March 1918. After additional training in aerial gunnery and artillery fire control, Lieutenant Keesler was assigned to the 24th Aero Squadron, in the Verdun sector on the Western Front, on 26 August 1918. During World War I, while performing a reconnaissance mission behind German lines in the late afternoon of 8 October 1918, Keesler and his pilot, First Lieutenant Harold W. Riley, came under heavy gunfire from four enemy aircraft. Riley quickly lost control of the badly damaged airplane while Keesler continued to fend off the attackers even as they plummeted to the ground. Seriously wounded during the battle and the ensuing crash land- ing, Keesler and Riley were eventually captured by German ground troops and held prisoner. Unable to receive immediate medical attention, Keesler died from his injuries the following day. -

Air Force Non-Rated Technical Training

C O R P O R A T I O N Air Force Non-Rated Technical TraJning Opportunities for Improving Pipeline Processes Lisa M. Harrington, Kathleen Reedy, John Ausink, Bart E. Bennett, Barbara A. Bicksler, Darrell Jones, Daniel Ibarra For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2116 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017961262 ISBN: 978-0-8330-9886-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface In recent years the Air Force has faced persistent resource constraints while trying to deliver necessary training to its new officer and enlisted forces. -

Military Aviation

V: Military aviation Eglin Air Force Base • Hurlburt Field • Duke Field • Fort Rucker • Camp Shelby NAS Whiting Field • NAS Pensacola • Coast Guard Air Station New Orleans National Guard Combat Readiness Training Center • Tyndall Air Force Base Coast Guard Aviation Training Center Mobile • Keesler Air Force Base U.S. Air Force photo by Capt. Ryan Seymour Gulf Coast Aerospace Corridor 2012-2013 – 60 Chapter V - Military aviation Gulf Coast military machine The Gulf Coast region has Mississippi Alabama 47 military “sites” big and Florida little valued at $20.3 billion, and locals are taking steps Louisiana to protect them... Tcp illustration, Google Earth map ear Adm. Kevin Delaney, who sits on a Florida task force created to Story at a glance protect the state’s military bases, re- • Three Gulf Coast I-10 bases are among cently observed that “when the stars the nation’s largest in replacement value Rgo away, missions tend to follow.” • 12 bases aviation focused, including He was talking about shoulder board stars of pilot training, weapons development generals, and the Air • Region hosts three commands, one Force’s plans to elimi- involved in aviation activities nate a two-star post at • U.S. Air Force Contractors in region awarded $55 Eglin Air Force Base billion from military between 2000-2011 and have a test wing answer to a two-star in California. The fear is it may foreshadow an • Home to one of the nation’s four ANG eventual move . combat readiness training centers The concerns of Northwest Florida, where the military has a $17 billion economic impact, are not unique. -

Operation Dragon Comeback

Operation Dragon Comeback Air Education and Training Command’s Response to Hurricane Katrina Dr. Bruce A. Ashcroft Dr. Joseph L. Mason Air Education and Training Command Office of History and Research Air Force History and Museums Program United States Air Force Washington, D.C., 2006 Preface The Air Education and Training Command’s response to Hurricane Katrina was a pivotal event in the organization’s history. Unlike previous storms that shut down training for a day or two, Katrina caused serious problems. In a fast-paced disaster response, often the information most significant to the historical record is not available in written documents, making interviews essential. This study rests solidly on a series of oral history interviews conducted at several AETC bases by the command’s historians with 65 members of the command and other participants in the relief effort. In addition, Dr Bruce Ashcroft and Dr Joseph Mason had extensive informal discussions with AETC members, and Dr Ashcroft attended meetings of the technical training reconstitution Tiger Team. Throughout the effort, AETC historians collected documents that underpinned the information gathered in interviews. The authors attempted to cover not only the hurricane, but also, and perhaps more importantly, the first few months of the recovery effort. Chapter 1 deals with the preparations and initial response to the devastation Hurricane Katrina wrought on Keesler AFB. It covers the first few days of digging out after the destructive storm, evacuating students to Sheppard AFB, and evacuating medical patients from the base, as well as the welcoming of Air Force evacuees to Maxwell and Columbus AFBs. -

Major Commands

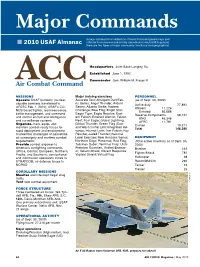

Major Commands A major command is a subdivision of the Air Force assigned a major part of the Air Force mission and directly subordinate to Hg. USAF. In general, there are two types of major commands: operational and support. Air Combat Command Headquarters Langley AFB, Va. Established June 1, 1992 Commander Gen. Richard E. Hawley MISSIONS Operate USAF bombers Operate USAF's CON US-based, combat-coded fighter and attack aircraft Organize, train, equip, and maintain combat-ready forces Provide nuclear-capable forces for US Strategic Command COROLLARY MISSIONS Monitor and intercept illegal drug traffic Test new combat equipment OTHER RESPONSIBILITIES Supply aircraft to the five geo- graphic unified commands: Atlantic, European, Pacific, Southern, and Central Commands Provide air defense forces to North American Aerospace De- fense Command Eight wings in Air Combat Command fly the F-16 Fighting Falcon, one of the Operate certain air mobility forces most versatile fighter aircraft in USAF history. These Block 50 F-16Cs from the in support of US Transportation 78th Fighter Squadron, Shaw AFB, S. C., have begun taking on a new spe- Command cialty—the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses mission. EQUIPMENT (Primary Aircraft Inventory) AFB, La.; 9th, Shaw AFB, S. C.; OPERATIONAL ACTIVITY Bombers (B-1B, B-2, B-52) 123 12th, Davis-Monthan AFB, Ariz. Flying hours 45,000 per month Fighters (F-15A/C, F-16) 324 One direct reporting unit: Air War- Major overseas deployments Attack aircraft (A/OA-10, F-1 5E, fare Center Bright Star (Central Command), F-111, F-117) 225 Twenty -s wings Central Enterprise, Crested Cap EC/EW aircraft (F-4G, EF-111).. -

Major Commands

Major Commands A major command is a subdivision of the Air Force assigned a major part of the Air Force mission and directly subordinate to Hq. USAF. In general, ■ 2010 USAF Almanac there are two types of major commands: functional and geographical. Headquarters Joint Base Langley, Va. Established June 1, 1992 Commander Gen. William M. Fraser III AirACC Combat Command Missions Major training exercises PErsonnEl operate USAF bombers (nuclear- Accurate Test; Amalgam Dart/Fab- (as of Sept. 30, 2009) capable bombers transferred to ric Series; Angel Thunder; Ardent Active duty 77,892 AFGSC Feb. 1, 2010); USAF’s CO- Sentry; Atlantic Strike; Austere Officers 11,226 NUS-based fighter, reconnaissance, Challenge; Blue Flag; Bright Star; Enlisted 66,666 battle management, and command Eager Tiger; Eagle Resolve; East- Reserve Components 58,127 and control aircraft and intelligence ern Falcon; Emerald Warrior; Falcon ANG 46,346 and surveillance systems Nest; Foal Eagle; Global Lightning; AFRC 11,781 organize, train, equip, and Global Thunder; Green Flag (East Civilian 10,371 maintain combat-ready forces for and West); Initial Link; Integrated Ad- Total 146,390 rapid deployment and employment vance; Internal Look; Iron Falcon; Key to meet the challenges of peacetime Resolve; Jaded Thunder; National air sovereignty and wartime combat Level Exercise; New Horizons Series; EquipmenT requirements Northern Edge; Panamax; Red Flag; (Total active inventory as of Sept. 30, Provide combat airpower to Talisman Saber; Terminal Fury; Ulchi 2009) America’s warfighting -

Combined Federal Campaign Set to Kick

FRIDAY, AUGUST 28, 2009 GATEWAY TO THE AIR FORCE • LACKLAND AIR FORCE BASE, TEXAS • www.lackland.af.mil • Vol. 67 No. 33 STARTING A NEW SCHOOL YEAR INSIDE Commentary 4 Straight Talk 5 Recognition 6 News & Features E-5 Promotion list 8 Gunfighters 12 AF Ball set 13 Photo by Alan Boedeker Students at Lackland Elementary School recite the Pledge of Allegiance Monday before their first day of school. Combined federal campaign set to kick off Benefit golf tourney 20 By Mike Joseph Wing commander, said the CFC offers a Last year’s campaign exceeded $1.2 Staff Writer tremendous opportunity for Airmen to million, well over the goal of nearly make a difference. $850,000. Open to all federal employees, The annual Combined Federal “CFC provides the opportunity to give the CFC reaches all Lackland agencies, Campaign, which raises money each year back to the community; we can give sup- each with a separate fundraising goal. for local, national and international chari- port locally and nationally,” he said. They include the 37th Training Wing, 59th ties, gets underway Wednesday morning “Last year we met our goal for perma- Medical Wing, the Air Force Intelligence, with a kickoff breakfast at the Gateway nent party and exceeded our goal for Surveillance and Reconnaissance Agency, Club. trainees,” said Lt. Col. Enrique Gwin, Team the 149th Fighter Wing and the 433rd The formal campaign runs Wednesday Lackland project officer for the campaign. Airlift Wing. View the Talespinner online through Oct. 14, but funds will be collected “Because of the economic conditions, the “I personally think we will meet the at www.lackland.af.mil through Dec.