HARMEYER-THESIS-2013.Pdf (5.266Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi English Glossary

Hindi - English Glossary A glossary of commonly appearing words in murlis and clarifications Sr. No. Hindi word Transcription English meaning 1 vk/;kfRed Aadhyaatmik Adhi -inside, aatmik -of the soul; that which is inside the soul 2 vkfn nso Aadi dev The first deity 3 vkfn nsoh Aadi devi The first female deity 4 vkdkjh Aakaari Subtle 5 vkj.;d Aaranyak The name of a class of vedic literature closely connected with the Brahmins 6 vkRefu"B Aatmanishth The one who has realized the self / the one who is in the soul conscious stage 7 vHkksxrk Abhogta The one who doesn't experience pleasure 8 v/kj dqekj Adhar kumar Married man who leads a pure life 9 v/kj dqekjh Adhar kumari Married woman who leads a pure life 10 vk/kkjewrZ Adharmurt Supporting soul / root form soul 11 vf/kdkjh Adhikaari Ruler, officer Myth. wife of Sage Gautam who was cursed to become 12 vfgY;k Ahilya a stone; here it means, the one with a stone like intellect 13 vtUek Ajanma The one who isn’t born 14 vdkyewrZ Akaalmuurt The one whose body can't be devoured by death; the imperishable personality 15 vdeZ Akarma neutral actions; actions that have no karmic return 16 vdrkZ Akarta The one who doesn’t perform actions 17 v{kj Akshar The one who doesn't fall/doesn't get discharged 18 vyQ Alaf First letter in the Urdu language; vertical line 19 vykSfdd Alaukik not from this world / unworldly 20 veu Aman The one who doesn't have a mind, peaceful 21 vejdFkk Amarkatha The story of immortality 22 vejyksd Amarlok The abode of immortality 23 vejukFk Amarnaath The lord of the immortals 24 -

12 CEMETERY SUPERSTITIONS by Cathy Wallace

12 CEMETERY SUPERSTITIONS By Cathy Wallace, Cemetery superstitions from the last century or two may have more influence over how you behave when it comes to family funerals and burials than you might realize. Have you ever worn black to a funeral? Did you travel from a funeral home to the cemetery in an unbroken procession of cars? Have you ever sent flowers to the family of the deceased? Why did you do those things? Tradition? Where did those traditions come from? Many of them came from century-old cemetery superstitions. Cemetery Superstitions #1: Wearing Black The custom of wearing black at funerals is an ancient one, but it became more popular during the Victorian era. Black was believed to make the living less visible to the spirits that came to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. After all, they didn’t want the spirits to make any mistakes and take them along too! If a family could not afford black clothing, it was acceptable to wear a black armband. Widows were expected to wear black for two years after their spouse died. But during the last six months of this period, they could add some trim in grey, white, or lavender. Cemetery Superstitions #2: Stop the Clock When someone died, clocks were stopped at the moment of death. For practical reasons, this would allow for an accurate doctor’s report and death certificate. But it was also said to be out of respect for the dead. Time had stopped for their mortal life and so their spirit must not be rushed into leaving too quickly by allowing them to notice the passage of time. -

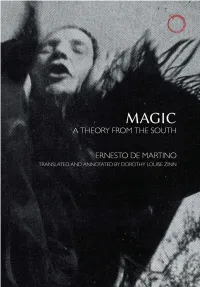

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

An Examination of Intention-Based Contagion

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 11, No. 6, November 2016, pp. 554–571 Contamination without contact: An examination of intention-based contagion Olga Stavrova∗ George E. Newman† Anna Kulemann‡ Detlef Fetchenhauer § Abstract Contagion refers to the belief that individuals or objects can acquire the essence of a particular source, such as a disgusting product or an immoral person, through physical contact. This paper documents beliefs in a "contact-free" form of contagion whereby an object is thought to inherit the essence of a person when it was designed, but never actually physically touched, by the individual. We refer to this phenomenon as contagion through creative intent or "intention-based contagion" and distinguish it from more traditional forms of contact-based contagion (Studies 1 and 2), as well as alternative mechanisms such as mere association (Studies 2 and 3a). We demonstrate that, like contact-based contagion, intention-based contagion results from beliefs in transferred essence (Study 1) and involves beliefs in transfer of actual properties (Study 4). However, unlike contact-based contagion, intention-based contagion does not appear to be as strongly related to the emotion of disgust (Study 1) and can influence evaluations in auditory as well as visual modalities (Studies 3a–3c). Keywords: sympathetic magic, music, contagion, morality. 1 Introduction Wolf, 2008); and even the choice of organ transplant donors (Hood, Gjersoe, Donnelly, Byers & Itajkura, 2011; Meyer, People are averse to objects that were once in contact with Leslie, Gelman & Stilwell, 2013). disliked or disgusting sources such as a sweater worn by a Historically, researchers have emphasized the importance serial killer, or a hat that belonged to a Nazi officer (Hood, of physical contact in motivating contagion effects. -

Aam Aadmi 12 Dr

MORPARIA’S PAGE E-mail: [email protected] Contents FEBRUARY 2014 VOL.17/7 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ THEME: Morparia’s page 2 The Comman Man The Common Man Speaks 5 V Gangadhar The Common Man is surging 6 Managing editor Prof. Yogesh Atal Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde The ubiquitous ‘Common Man’ of India 8 P. Radhakrishnan Editor R.K Laxman: An Uncommon Common Man 10 Anuradha Dhareshwar V. Gangadhar The rise of the Aam Aadmi 12 Dr. Bhalchandra K. Kango Sub editor Right to Information – path to Swaraj 14 Sonam Saigal Shailesh Gandhi Aam Aadmi crusaders Design 6 Baba Amte 16 H. V. Shiv Shankar Adv. Varsha Deshpande 18 Rajendra Singh 19 Marketing Dr. Anil Joshi 20 Mahesh Kanojia Adv. M. C. Mehta 21 Anna Hazare 22 OIOP Clubs Know India Better Vaibhav Palkar How Beautiful is My Valley 23 Gustasp and Jeroo Irani Face to face: Shashi Deshpande 36 Subscription Features Nagesh Bangera Youth Voice - Urvish Mehta 40 Will Aam Aadmi Party survive as a National Party? 41 Prof. P M Kamath Advisory board 23 M V Kamath Khobragade episode triggers a much needed Sucharita Hegde correction 43 Justice S Radhakrishnan Dr. B. Ramesh Babu Venkat R Chary A memorable day 46 Lt. General Vijay Oberoi Printed & Published by Cultural Kaleidoscope 48 Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde for Navigation in ancient India and social taboo One India One People Foundation, against overseas travel 50 Mahalaxmi Chambers, 4th floor, B.M.N. Murthy 22, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Columns 52 Mumbai - 400 026 Nature watch : Bittu Sahgal Tel: 022-2353 4400 Infocus : C. V. Aravind Fax: 022-2351 7544 36 Young India 54 e-mail: [email protected] / Shashi Deshpande Great Indians 56 [email protected] Printed at: Graphtone (India) Pvt. -

The Material Culture of Love and Loss in Eighteenth-Century England Jennifer A

‘I mourn for them I loved’: The Material Culture of Love and Loss in Eighteenth-Century England Jennifer A. Jorm Bachelor of Arts (History) Honours Class 1 A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry i Abstract This thesis analyses the material culture of love and loss in eighteenth-century England through the lens of emotions. My study builds on scholarly works on material culture, emotions, death, love, and loss. It examines objects used to declare love, to express grief, and to say farewell. Chapter One introduces the historiography of this topic, outlines the methodology used, and problematises the issues and questions surrounding the relationship between individuals and objects during this period, such as the eighteenth century “consumer revolution,” and the rise of sentimentalism. This chapter also introduces what I term the “emotional economy,” or the value placed on an object based on emotional signficance regardless of its intrinsic value. Chapter Two explores love tokens and the role they played in not only the expression of romantic love, but the making and breaking of courtships and marriages. This chapter concludes that the exchange of tokens was vital to the expression of love, and was an expected emotional behaviour to progress a courtship into a marriage. Chapter Three explores the material culture of death, focusing on tokens created and distributed for the comforting of mourners, and the commemoration of the dead. It’s findings confirmed that mourners valued tokens and jewellery, particularly those made with hair belonging to the deceased in order to maintain a physical connection to their loved ones after their passing. -

Greenbird's Cursed Inventory II the Unholy Return

Greenbird's Cursed Inventory II The Unholy Return Amulet of the Water-bride The Baron's Mirror Wondrous Item, very rare Wondrous Item, very rare A rather heavy amulet of silver chains Baron Von Blatzvunschendelbrun encasing a beautiful, oval sapphire jew- mysteriously died of a flesh eating el. It has enchanted many a soul, some- disease, which, despite the disease’s times rendering them enchanting in horrific nature, did not spread to the turn. The beauty of the amulet inspires rest of his household. It is little known the wearer, and they gain +2 charisma that, as well being incredibly vain, he while wearing it. However, the amulet was a brute to his servants and serfs. can render its wearer possessive and One evening, after he had gone to bed, jealous, making them unwilling to part those servants who had borne the brunt with it for any reason. of his viciousness gathered in the basement and debased their souls to the Should the wearer enter a chest-deep dark powers. They summoned an evil body of water, the amulet bursts with energy into the mirror into which he malicious power, magically gaining gazed for hours every day. The Baron extra weight (an additional 50 pounds). died a month later in incredible agony. This often causes lethal injuries to the neck, or leaves the victims unable to When you gaze upon your reflection in remove the cursed jewelry before they this mirror make a wisdom save DC15 drown. Somehow, years or decades or be stricken with a flesh eating disease. later, the amulet is flushed to the shore, The disease can be cured by one of the bound to find another unfortunate soul. -

Nineteenth-Century Memorial Jewellery at Canterbury Museum

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2020 Vol. 34: 63–84 63 Any relic of the dead is precious: Nineteenth-century memorial jewellery at Canterbury Museum Lyndon Fraser1 and Julia Bradshaw2 1University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] 2Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Avenue, Christchurch 8013, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Canterbury Museum houses a small but varied collection of memorial jewellery from the nineteenth century that provides a window into European relationships and deathways during the period. This article places these objects in the context of far-reaching changes that led to a new social order of the dead. The first section locates our work within historical writing on death, grief and mourning in the late Georgian and Victorian eras. In the second, we attempt to make sense of the material evidence and offer a close analysis of the various mementos. We argue that these keepsakes played a crucial consolatory role in mourning practices at the time and assisted the bereaved to come to terms with their loss. Keywords: death, memorials, memory, migration, mourning jewellery, nineteenth century Introduction Canterbury Museum holds a collection of Père-Lachaise in Paris, shortly after Napoleon items that have an intimate connection to was crowned emperor. Designed by architect people’s emotions and memories: items of Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart and modelled jewellery that were created as love tokens on the ancient site of Karameikos in Athens, and memorials to the dead. The collection this modern Elysium set a high international encompasses jewellery made from jet, metal, standard for spaces of the dead and gave rise semi-precious stones and, most intimate of to a new necro-geography. -

Oxford by the Numbers: What Are the Odds That the Earl of Oxford Could Have Written Shakespeare’S Poems and Plays?

OXFORD BY THE NUMBERS: WHAT ARE THE ODDS THAT THE EARL OF OXFORD COULD HAVE WRITTEN SHAKESPEARE’S POEMS AND PLAYS? WARD E.Y. ELLIOTT AND ROBERT J. VALENZA* Alan Nelson and Steven May, the two leading Oxford documents scholars in the world, have shown that, although many documents connect William Shakspere of Stratford to Shakespeare’s poems and plays, no documents make a similar connection for Oxford. The documents, they say, support Shakespeare, not Oxford. Our internal- evidence stylometric tests provide no support for Oxford. In terms of quantifiable stylistic attributes, Oxford’s verse and Shakespeare’s verse are light years apart. The odds that either could have written the other’s work are much lower than the odds of getting hit by lightning. Several of Shakespeare’s stylistic habits did change during his writing lifetime and continued to change years after Oxford’s death. Oxfordian efforts to fix this problem by conjecturally re-dating the plays twelve years earlier have not helped his case. The re-datings are likewise ill- documented or undocumented, and even if they were substantiated, they would only make Oxford’s stylistic mismatches with early Shakespeare more glaring. Some Oxfordians now concede that Oxford differs from Shakespeare but argue that the differences are developmental, like those between a caterpillar and a butterfly. This argument is neither documented nor plausible. It asks us to believe, without supporting evidence, that at age forty-three, Oxford abruptly changed seven to nine of his previously constant writing habits to match those of Shakespeare and then froze all but four habits again into Shakespeare’s likeness for the rest of his writing days. -

1999 Dr Susan Aykut, Hairy Politics: Hair Rituals in Ottoman and Turkish

THE JUNIOR CHARLES STRONG TRUST LECTURE 1999 Hairy politics: hair rituals in Ottoman and Turkish society by Susan Aykut LaTrobe University delivered at the 24th Annual Conference of the Australian Association for the Study of Religions Sydney October 1999 CHARLES STRONG (Australian Church) MEMORIAL TRUST for the promotion in Australia of the sympathetic study of world religions THE CHARLES STRONG MEMORIAL TRUST Hairy politics: hair rituals in Ottoman and Turkish society Junior Charles Strong Trust Lecture 1999 Susan Aykut LaTrobe University In May 1999 a furor erupted in the Turkish parliament. A new member of parliament insisted that she be sworn in while ‘covered’—that is, wearing a headscarf covering her hair and shoulders but not her face, conveying her Islamic religious affiliation. The demand was denied. The acting speaker of parliament was instructed by an angry Prime Minister, Bülent Ecevit, to ‘Please put this lady in her place’.1 There are plenty of political wranglings and interesting scenarios to pursue about the parliamentary debacle just mentioned2 but the two big questions it raises, which I want to explore in this paper, are: firstly, what is the significance of headdress and of hair for the Turks; and, secondly, where is the place of Islam today in the secularised nation state of Turkey—or, in other words, where does the Prime Minister want to put the ‘covered’ female MP? The two questions are linked. For the last 600 years at least, the way hair is groomed and what headdress is worn has been significant in defining the allegiances of Turks to the state. -

Bible and Religion, Fine Arts, Math and Science 1

constant0704final.qxd 8/4/2004 2:37 PM Page 2 By John P. Campbell Campbell’s High School/College Quiz Book Campbell’s Potpourri I of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Potpourri II of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Middle School Quiz Book #1 Campbell’s Potpourri III of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Middle School Quiz Book #2 Campbell’s Elementary School Quiz Book #1 Campbell’s 2001 Quiz Questions Campbell’s Potpourri IV of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Middle School Quiz Book #3 The 500 Famous Quotations Quiz Book Campbell’s 2002 Quiz Questions Campbell’s 210 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s 175 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s 2003 Quiz Questions Campbell’s 211 Lightning Rounds OmniscienceTM: The Basic Game of Knowledge in Book Form Campbell’s 2004 Quiz Questions Campbell’s 212 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s Elementary School Quiz Book #2 Campbell’s 176 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s 213 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s Potpourri V of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Mastering the Myths in a Giant Nutshell Quiz Book Campbell’s 3001 Quiz Questions Campbell’s 2701 Quiz Questions Campbell’s Quiz Book on Explorations and U.S. History to 1865 Campbell’s Accent Cubed: Humanities, Math, and Science Campbell’s 2501 Quiz Questions Campbell’s Accent on the Alphabet Quiz Book Campbell’s U.S. History 1866 to 1960 Quiz Book Campbell’s 177 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s 214 Lightning Rounds Campbell’s Potpourri VI of Quiz Bowl Questions Campbell’s Middle School Quiz Book #4 Campbell’s 2005 Quiz Questions Campbell’s High School/College Book of Lists constant0704final.qxd 8/4/2004 2:37 PM Page 3 CAMPBELL’S CONSTANT QUIZ COMPANION: THE MIDDLE/HIGH SCHOOL BOOK OF LISTS, TERMS, AND QUESTIONS REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION JOHN P. -

Aztec Human Sacrifice As Entertainment? the Physio-Psycho- Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho- Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations Linda Jane Hansen University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Linda Jane, "Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho-Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1287. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1287 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. AZTEC HUMAN SACRIFICE AS ENTERTAINMENT? THE PHYSIO-PSYCHO-SOCIAL REWARDS OF AZTEC SACRIFICIAL CELEBRATIONS ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Linda Prueitt Hansen June 2017 Advisor: Dr. Annabeth Headrick ©Copyright by Linda Prueitt Hansen 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Linda Prueitt Hansen Title: Aztec Human Sacrifice as Entertainment? The Physio-Psycho-Social Rewards of Aztec Sacrificial Celebrations Advisor: Dr. Annabeth Headrick Degree Date: June 2017 ABSTRACT Human sacrifice in the sixteenth-century Aztec Empire, as recorded by Spanish chroniclers, was conducted on a large scale and was usually the climactic ritual act culminating elaborate multi-day festivals.