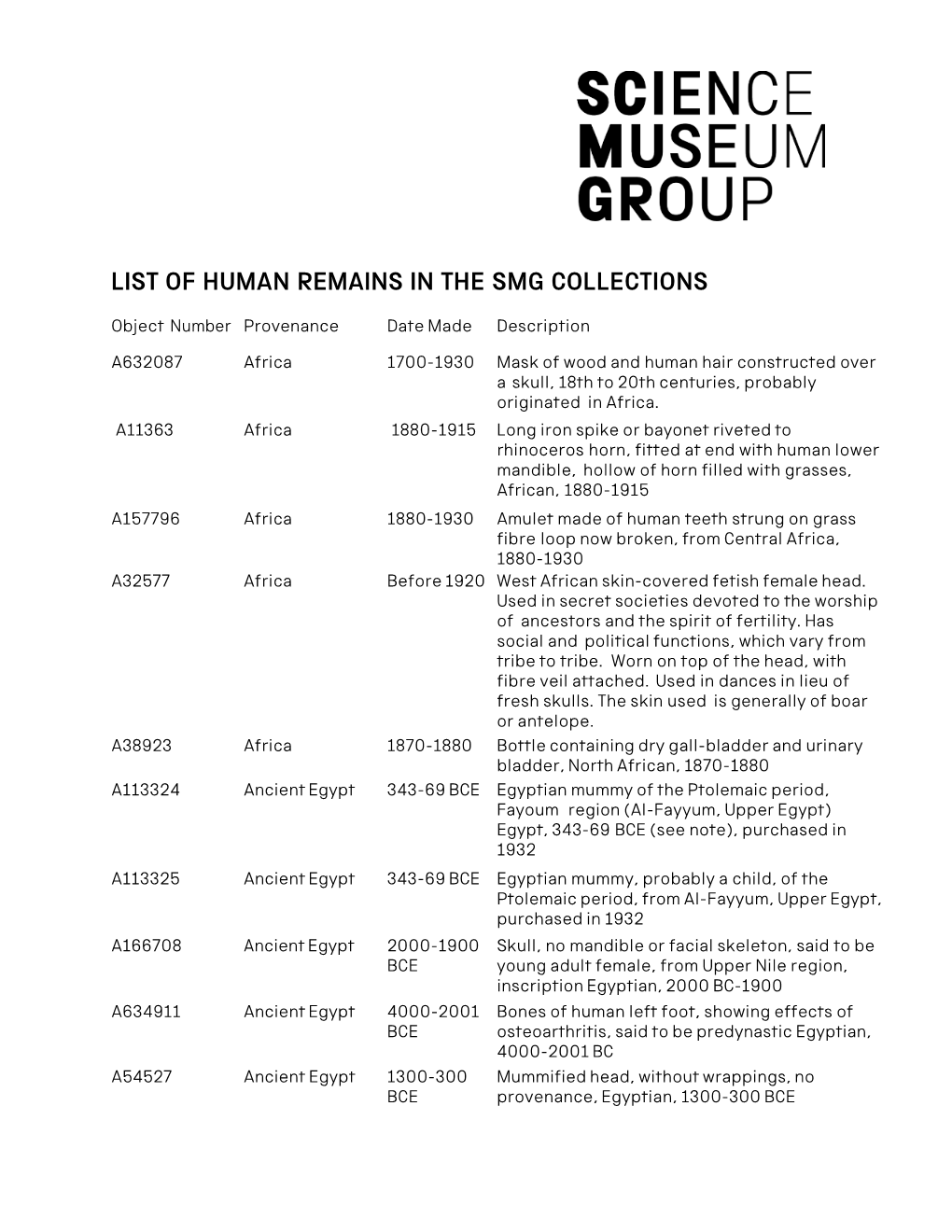

List of Human Remains in the Smg Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Human Mandibular Variation Reflects Differences in Agricultural

Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel1 Department of Anthropology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, Canterbury CT2 7NR, United Kingdom Edited by Timothy D. Weaver, University of California, Davis, CA, and accepted by the Editorial Board October 19, 2011 (received for review August 12, 2011) Variation in the masticatory behavior of hunter-gatherer and has been found (14, 15) that global patterns of mandibular var- agricultural populations is hypothesized to be one of the major iation do not follow a model of neutral evolution. forces affecting the form of the human mandible. However, this If the null model of evolutionary neutrality can be rejected for has yet to be analyzed at a global level. Here, the relationship global patterns of human mandibular variation, alternative non- between global mandibular shape variation and subsistence eco- neutral hypotheses must be considered. One of the most obvious nomy is tested, while controlling for the potentially confounding alternative models is that agricultural populations will experience effects of shared population history, geography, and climate. The different biomechanical or selective pressures on mandibular results demonstrate that the mandible, in contrast to the cranium, shape than hunter-gatherers, such that modifications have occurred significantly reflects subsistence strategy rather than neutral either via phenotypic plasticity or natural selection. Previous genetic patterns, with hunter-gatherers having consistently longer morphometric studies (23, 24) found some geographical patterning and narrower mandibles than agriculturalists. These results sup- in mandibular morphology, as well as a signal of climatic and/or port notions that a decrease in masticatory stress among agricul- masticatory plasticity. -

Standard Human Facial Proportions

Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: __________________ Standard Human Facial Proportions: The standard proportions for the human head can help you place facial features and find their orientation. The list below gives an idea of ideal proportions. • The eyes are halfway between the top of the head and the chin. • The face is divided into 3 parts from the hairline to the eyebrow, from the eyebrow to the bottom of the nose, and from the nose to the chin. • The bottom of the nose is halfway between the eyes and the chin. • The mouth is one third of the distance between the nose and the chin. • The distance between the eyes is equal to the width of one eye. • The face is about the width of five eyes and about the height of about seven eyes. • The base of the nose is about the width of the eye. • The mouth at rest is about the width of an eye. • The corners of the mouth line up with the centers of the eye. Their width is the distance between the pupils of the eye. • The top of the ears line up slightly above the eyes in line with the outer tips of the eyebrows. • The bottom of the ears line up with the bottom of the nose. • The width of the shoulders is equal to two head lengths. • The width of the neck is about ½ a head. Facial Feature Examples.docx Page 1 of 13 Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: __________________ PROFILE FACIAL PROPORTIONS Facial Feature Examples.docx Page 2 of 13 Name:_____________________________________________ Date:__________________Period: -

The Development of a Whole-Head Human Finite- Element Model for Simulation of the Transmission of Bone-Conducted Sound

The development of a whole-head human finite- element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound You Chang, Namkeun Kim and Stefan Stenfelt Journal Article N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: You Chang, Namkeun Kim and Stefan Stenfelt, The development of a whole-head human finite-element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 2016. 140(3), pp.1635-1651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.4962443 Copyright: Acoustical Society of America / Nature Publishing Group http://acousticalsociety.org/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-133011 The development of a whole-head human finite-element model for simulation of the transmission of bone-conducted sound You Chang1), Namkeun Kim2), and Stefan Stenfelt1) 1) Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 2) Division of Mechanical System Engineering, Incheon National University, Incheon, Korea Running title: whole-head finite-element model for bone conduction 1 Abstract A whole head finite element model for simulation of bone conducted (BC) sound transmission was developed. The geometry and structures were identified from cryosectional images of a female human head and 8 different components were included in the model: cerebrospinal fluid, brain, three layers of bone, soft tissue, eye and cartilage. The skull bone was modeled as a sandwich structure with an inner and outer layer of cortical bone and soft spongy bone (diploë) in between. The behavior of the finite element model was validated against experimental data of mechanical point impedance, vibration of the cochlear promontories, and transcranial BC sound transmission. -

Comparison of Cadaveric Human Head Mass Properties: Mechanical Measurement Vs

12 INJURY BIOMECHANICS RESEARCH Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Workshop Comparison of Cadaveric Human Head Mass Properties: Mechanical Measurement vs. Calculation from Medical Imaging C. Albery and J. J. Whitestone This paper has not been screened for accuracy nor refereed by any body of scientific peers and should not be referenced in the open literature. ABSTRACT In order to accurately simulate the dynamics of the head and neck in impact and acceleration environments, valid mass properties data for the human head must exist. The mechanical techniques used to measure the mass properties of segmented cadaveric and manikin heads cannot be used on live human subjects. Recent advancements in medical imaging allow for three-dimensional representation of all tissue components of the living and cadaveric human head that can be used to calculate mass properties. A comparison was conducted between the measured mass properties and those calculated from medical images for 15 human cadaveric heads in order to validate this new method. Specimens for this study included seven female and eight male, unembalmed human cadaveric heads (ages 16 to 97; mean = 59±22). Specimen weight, center of gravity (CG), and principal moments of inertia (MOI) were mechanically measured (Baughn et al., 1995, Self et al., 1992). These mass properties were also calculated from computerized tomography (CT) data. The CT scan data were segmented into three tissue types - brain, bone, and skin. Specific gravity was assigned to each tissue type based on values from the literature (Clauser et al., 1969). Through analysis of the binary volumetric data, the weight, CG, and MOIs were determined. -

Adult Human Ocular Volume

ogy: iol Cu ys r h re P n t & R y e s Anatomy & Physiology: Current m e o a t r a c n h Heymsfield et al., Anat Physiol 2016, 6:5 A Research ISSN: 2161-0940 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0940.1000239 Research Article Open Access Adult Human Ocular Volume: Scaling to Body Size and Composition Steven B Heymsfield1*, Cristina Gonzalez M2, Diana Thomas3, Kori Murray1, Guang Jia4, Erik Cattrysse5, Jan Pieter Clarys5,6 and Aldo Scafoglieri5 1Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, USA 2Post-Graduation Program in Health and Behavior, Catholic University of Pelotas, Brazil 3Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ, USA 4Department of Medical Physics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, USA 5Experimental Anatomy Research Department, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium 6Radiology Department, University Hospital Brussels, Brussels, Belgium *Corresponding author: Steven B Heymsfield, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, 6400 Perkins Rd., Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA, Tel: 225-763-2541; Fax: 225-763-0935; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: August 6, 2016; Accepted date: August 24, 2016; Published date: August 30, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Heymsfield SB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Objectives: Little is currently known on how human ocular volume (OV) relates to body size or composition across adult men and women. This gap was filled in an exploratory study on the path to developing anthropological and physiological models by measuring OV in young healthy adults and related brain, head, and body mass along with major body components. -

Hindi English Glossary

Hindi - English Glossary A glossary of commonly appearing words in murlis and clarifications Sr. No. Hindi word Transcription English meaning 1 vk/;kfRed Aadhyaatmik Adhi -inside, aatmik -of the soul; that which is inside the soul 2 vkfn nso Aadi dev The first deity 3 vkfn nsoh Aadi devi The first female deity 4 vkdkjh Aakaari Subtle 5 vkj.;d Aaranyak The name of a class of vedic literature closely connected with the Brahmins 6 vkRefu"B Aatmanishth The one who has realized the self / the one who is in the soul conscious stage 7 vHkksxrk Abhogta The one who doesn't experience pleasure 8 v/kj dqekj Adhar kumar Married man who leads a pure life 9 v/kj dqekjh Adhar kumari Married woman who leads a pure life 10 vk/kkjewrZ Adharmurt Supporting soul / root form soul 11 vf/kdkjh Adhikaari Ruler, officer Myth. wife of Sage Gautam who was cursed to become 12 vfgY;k Ahilya a stone; here it means, the one with a stone like intellect 13 vtUek Ajanma The one who isn’t born 14 vdkyewrZ Akaalmuurt The one whose body can't be devoured by death; the imperishable personality 15 vdeZ Akarma neutral actions; actions that have no karmic return 16 vdrkZ Akarta The one who doesn’t perform actions 17 v{kj Akshar The one who doesn't fall/doesn't get discharged 18 vyQ Alaf First letter in the Urdu language; vertical line 19 vykSfdd Alaukik not from this world / unworldly 20 veu Aman The one who doesn't have a mind, peaceful 21 vejdFkk Amarkatha The story of immortality 22 vejyksd Amarlok The abode of immortality 23 vejukFk Amarnaath The lord of the immortals 24 -

12 CEMETERY SUPERSTITIONS by Cathy Wallace

12 CEMETERY SUPERSTITIONS By Cathy Wallace, Cemetery superstitions from the last century or two may have more influence over how you behave when it comes to family funerals and burials than you might realize. Have you ever worn black to a funeral? Did you travel from a funeral home to the cemetery in an unbroken procession of cars? Have you ever sent flowers to the family of the deceased? Why did you do those things? Tradition? Where did those traditions come from? Many of them came from century-old cemetery superstitions. Cemetery Superstitions #1: Wearing Black The custom of wearing black at funerals is an ancient one, but it became more popular during the Victorian era. Black was believed to make the living less visible to the spirits that came to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. After all, they didn’t want the spirits to make any mistakes and take them along too! If a family could not afford black clothing, it was acceptable to wear a black armband. Widows were expected to wear black for two years after their spouse died. But during the last six months of this period, they could add some trim in grey, white, or lavender. Cemetery Superstitions #2: Stop the Clock When someone died, clocks were stopped at the moment of death. For practical reasons, this would allow for an accurate doctor’s report and death certificate. But it was also said to be out of respect for the dead. Time had stopped for their mortal life and so their spirit must not be rushed into leaving too quickly by allowing them to notice the passage of time. -

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Physical and Geometric Constraints Shape the Labyrinth-Like Nasal Cavity

Physical and geometric constraints shape the labyrinth-like nasal cavity David Zwickera,b,1, Rodolfo Ostilla-Monico´ a,b, Daniel E. Liebermanc, and Michael P. Brennera,b aJohn A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; bKavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; and cDepartment of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Leslie Greengard, New York University, New York, NY, and approved January 26, 2018 (received for review August 29, 2017) The nasal cavity is a vital component of the respiratory system take into account geometric constraints imposed by the shape that heats and humidifies inhaled air in all vertebrates. Despite of the head that determine the length of the nasal cavity, its this common function, the shapes of nasal cavities vary widely cross-sectional area, and, generally, the shape of the space that it across animals. To understand this variability, we here connect occupies. To tackle this complex problem, we first show that, nasal geometry to its function by theoretically studying the air- without geometric constraints, optimal shapes have slender flow and the associated scalar exchange that describes heating cross-sections. We then demonstrate that these shapes can be and humidification. We find that optimal geometries, which have compacted into the typical labyrinth-like shapes without much minimal resistance for a given exchange efficiency, have a con- loss in performance. stant gap width between their side walls, while their overall shape can adhere to the geometric constraints imposed by the Results head. Our theory explains the geometric variations of natural The Flow in the Nasal Cavity Is Laminar. -

![Arxiv:2106.12302V1 [Cs.CV] 23 Jun 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6864/arxiv-2106-12302v1-cs-cv-23-jun-2021-1496864.webp)

Arxiv:2106.12302V1 [Cs.CV] 23 Jun 2021

3D human tongue reconstruction from single “in-the-wild” images Stylianos Ploumpis1;2 * Stylianos Moschoglou1;2 * Vasileios Triantafyllou2 Stefanos Zafeiriou1;2 1Imperial College London, UK 2Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd 1fs.ploumpis,s.moschoglou,[email protected] [email protected] Figure 1. We propose a framework that accurately derives the 3D tongue shape from single images. A high detailed 3D point cloud of the tongue surface and a full head topology along with the tongue expression can be estimated from the image domain. As we demonstrate, our framework is able to capture the tongue shape even in adverse “in-the-wild” conditions. Abstract dataset, consisting of 1; 800 raw scans of 700 individuals varying in gender, age, and ethnicity backgrounds *. As we 3D face reconstruction from a single image is a task demonstrate in an extensive series of quantitative as well that has garnered increased interest in the Computer Vision as qualitative experiments, our model proves to be robust community, especially due to its broad use in a number of and realistically captures the 3D tongue structure, even in applications such as realistic 3D avatar creation, pose in- adverse “in-the-wild” conditions. variant face recognition and face hallucination. Since the introduction of the 3D Morphable Model in the late 90’s, we witnessed an explosion of research aiming at particu- 1. Introduction larly tackling this task. Nevertheless, despite the increasing Recently, 3D face reconstruction from single “in-the- arXiv:2106.12302v1 [cs.CV] 23 Jun 2021 level of detail in the 3D face reconstructions from single wild” images has been a very active topic in Computer Vi- images mainly attributed to deep learning advances, finer sion with applications ranging from realistic 3D avatar cre- and highly deformable components of the face such as the ation to image imputation and face recognition [48, 17, 43, tongue are still absent from all 3D face models in the liter- 25, 41, 15]. -

Forensic Hair Comparisons

Forensic Hair Comparisons Max M. Houck Director, Forensic Science Initiative, Research Office Manager, Forensic Business Research and Development, College of Business and Economics Specific questions • What is the state of the art? –I hope this presentation demonstrates the state of the art • Where is research conducted? –Little research is conducted in forensic hair examinations, except for mtDNA • Where is it published? –When conducted, it is published in peer review journals Basis of forensic hair microscopy •Comparative biology, including medicine and physical anthropology, has a long history of microscopic identification and comparison dating back to the 18th century. – Comparison is the cornerstone of the majority of biology, both past and present. •Microscopic techniques, combined with studied experience, provide for a discriminating means to examine and compare hair. •Literature in physical anthropology and forensic science detailing the differences between peoples’hair supports the credibility of the science Victim and Criminal only Victim and Criminal interact at a interact at a Crime Scene Crime Scene familiar to both unfamiliar to both Ex. Spouse kills co-habitating Ex. Sexual assault in an alley spouse Victim and Criminal interact Victim and Criminal interact at a Crime Scene familiar at a Crime Scene familiar only only to the Criminal to the Victim Victim Ex. Kidnapping and assault in Ex. Home invasion Criminal’s house Criminal Crime Scene What can be determined? • Is it a hair? • Is it human? • What area of the body is -

An Examination of Intention-Based Contagion

Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 11, No. 6, November 2016, pp. 554–571 Contamination without contact: An examination of intention-based contagion Olga Stavrova∗ George E. Newman† Anna Kulemann‡ Detlef Fetchenhauer § Abstract Contagion refers to the belief that individuals or objects can acquire the essence of a particular source, such as a disgusting product or an immoral person, through physical contact. This paper documents beliefs in a "contact-free" form of contagion whereby an object is thought to inherit the essence of a person when it was designed, but never actually physically touched, by the individual. We refer to this phenomenon as contagion through creative intent or "intention-based contagion" and distinguish it from more traditional forms of contact-based contagion (Studies 1 and 2), as well as alternative mechanisms such as mere association (Studies 2 and 3a). We demonstrate that, like contact-based contagion, intention-based contagion results from beliefs in transferred essence (Study 1) and involves beliefs in transfer of actual properties (Study 4). However, unlike contact-based contagion, intention-based contagion does not appear to be as strongly related to the emotion of disgust (Study 1) and can influence evaluations in auditory as well as visual modalities (Studies 3a–3c). Keywords: sympathetic magic, music, contagion, morality. 1 Introduction Wolf, 2008); and even the choice of organ transplant donors (Hood, Gjersoe, Donnelly, Byers & Itajkura, 2011; Meyer, People are averse to objects that were once in contact with Leslie, Gelman & Stilwell, 2013). disliked or disgusting sources such as a sweater worn by a Historically, researchers have emphasized the importance serial killer, or a hat that belonged to a Nazi officer (Hood, of physical contact in motivating contagion effects.