Cúchulainn, Roosevelt and What It Means to Be Celtic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 7 1-29-2010 Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6. Emily McEwan-Fujita University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2010) "Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN:978-83-7171-849-6.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/7 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Celtic Presence: Studies in Celtic Languages and Literatures: Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Cornish. Piotr Stalmaszczyk. Łódź: Łódź University Press, Poland, 2005. Hardcover, 197 pages. ISBN: 978-83- 7171-849-6. $36.00. Emily McEwan-Fujita, University of Pittsburgh This book's central theme, as the author notes in the preface, is "dimensions of Celtic linguistic presence" as manifested in diverse sociolinguistic contexts. However, the concept of "linguistic presence" gives -

The Celtic Revival in English Literature, 1760-1800

ZOh. jU\j THE CELTIC REVIVAL IN ENGLISH LITERATURE LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The "Bard The Celtic Revival in English Literature 1760 — 1800 BY EDWARD D. SNYDER B.A. (Yale), Ph.D. (Harvard) CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1923 COPYRIGHT, 1923 BY HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINTED AT THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASS., U. S. A. PREFACE The wholesome tendency of modern scholarship to stop attempting a definition of romanticism and to turn instead to an intimate study of the pre-roman- tic poets, has led me to publish this volume, on which I have been intermittently engaged for several years. In selecting the approximate dates 1760 and 1800 for the limits, I have been more arbitrary in the later than in the earlier. The year 1760 has been selected because it marks, roughly speaking, the beginning of the Celtic Revival; whereas 1800, the end of the century, is little more than a con- venient place for breaking off a history that might have been continued, and may yet be continued, down to the present day. Even as the volume has been going through the press, I have found many new items from various obscure sources, and I am more than ever impressed with the fact that a collection of this sort can never be complete. I have made an effort, nevertheless, to show in detail what has been hastily sketched in countless histories of literature — the nature and extent of the Celtic Revival in the late eighteenth century. Most of the material here presented is now pub- lished for the first time. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

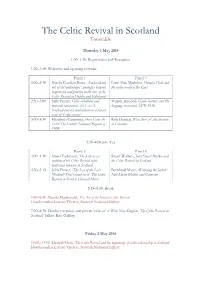

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable Thursday 1 May 2014 1:00–1:30: Registration and Reception 1:30–1:50: Welcome and opening remarks Panel 1 Panel 2 2:00–2:30 Nicola Gordon Bowe, ‘Embroideries Liam Mac Mathúna, Douglas Hyde and out of old mythologies’: analogies between the wider world of the Gael inspiration and practice in the arts of the Celtic Revival in Dublin and Edinburgh 2:30–3:00 Sally Foster, Celtic collections and Wilson McLeod, Gaelic learners and the imperial connections: the V&A, language movement, 1870-1930 Scotland and the multiplication of plaster casts of ‘Celtic crosses’ 3:00–3:30 Elizabeth Cumming, Here Come the Rob Dunbar, Was there a Celtic Revival Celts! The Scottish National Pageant of in Canada? 1908 3:30–4:00 pm: Tea Panel 3 Panel 4 4:00–4:30 Stuart Eydmann, The harp as an Stuart Wallace, John Stuart Blackie and emblem of the Celtic Revival, with the Celtic Revival in Scotland particular reference to Scotland 4:30–5.15 John Purser, ‘The Lay of the Last Bernhard Maier, ‘Widening the Jacket’: Minstrel? Don’t count on it’: The Celtic John Stuart Blackie and Germany Revival in Scottish Classical Music 5:15–5:30: Break 5:30–6:30: Murdo Macdonald, The Art of the Scottish Celtic Revival Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery 7:00–8:30: Drinks reception and private view of A Wide New Kingdom: The Celtic Revival in Scotland, Talbot Rice Gallery. Friday 2 May 2014 10:00–11:00: Donald Meek, The Celtic Revival and the beginnings of Celtic scholarship in Scotland Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish -

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers – the primary creative genius behind the famous British occult group, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – and his wife Moina Mathers established a mystery religion of Isis in fin-de-siècle Paris. Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, his wife Pamela, and his sister Olivia created the Fellowship of Isis in Ireland in the early 1970s. Although separated by over half a century, and not directly associated with each other, both groups have several characteristics in common. Each combined their worship of an ancient Egyptian goddess with an interest in the Celtic Revival; both claimed that their priestly lineages derived directly from the Egyptian queen Scota, mythical foundress of Ireland and Scotland; and both groups used dramatic ritual and theatrical events as avenues for the promulgation of their Isis cults. The Parisian Isis movement and the Fellowship of Isis were (and are) historically-inaccurate syncretic constructions that utilised the tradition of an Egyptian origin of the peoples of Scotland and Ireland to legitimise their founders’ claims of lineal descent from an ancient Egyptian priesthood. To explore this contention, this chapter begins with brief overviews of Isis in antiquity, her later appeal for Enlightenment Freemasons, and her subsequent adoption by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It then explores the Parisian cult of Isis, its relationship to the Celtic Revival, the myth of the Egyptian queen Scota, and examines the establishment of the Fellowship of Isis. The Parisian mysteries of Isis and the Fellowship of Isis have largely been overlooked by critical scholarship to date; the use of the medieval myth of Scota by the founders of these groups has hitherto been left unexplored. -

James Joyce, Catholicism, and the Celtic Revival in the Pre-Revolution Ireland of Dubliners Sean Clifford

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 5-13-2014 A Modernity Paused: James Joyce, Catholicism, and the Celtic Revival in the Pre-Revolution Ireland of Dubliners Sean Clifford Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Sean. (2014). A Modernity Paused: James Joyce, Catholicism, and the Celtic Revival in the Pre-Revolution Ireland of Dubliners. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 40. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/40 Copyright © 2014 Sean Clifford This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Clifford 1 A Modernity Paused: James Joyce, Catholicism, and the Celtic Revival in the Pre-Revolution Ireland of Dubliners Sean Clifford Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for Departmental Honors in English Bridgewater State University May 13, 2014 Dr. Ellen Scheible, Thesis Director Dr. Heidi Bean, Committee Member Prof. Bruce Machart, Committee Member Clifford 2 Sean Clifford Honors Thesis Bridgewater State University A Modernity Paused: James Joyce, Catholicism, and the Celtic Revival in the Pre-Revolution Ireland of Dubliners The Ireland of James Joyce’s first published work, Dubliners, is a nation only a few years away from revolution. It is a land still under the control of England and the specter of the Potato Famine. Charles Stuart Parnell’s push for Home Rule and his subsequent fall from grace and the failed revolutions of the past still lingered in its collective conscience. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm

4 (2017) Book Review 1: 1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN License: This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or is available from Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. © 2017 Philip Freeman Entangled Religions 4 (2017) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v4.2017.1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN The modern scholarly and popular fascination with the myths and religion of the early Celts shows no signs of abating—and with good reason. The stories of druids, gods, and heroes from ancient Gaul to medieval Ireland and Wales are among the best European culture has to offer. But what can we really know about the religion and mythology of the Celts? How do we discover genuine pre-Christian beliefs when almost all of our evidence comes from medieval Christian authors? Is the concept of “Celtic” even a valid one? These and other questions are addressed ably in this short collection of papers by some of the leading scholars in the field of Celtic studies. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

What's It Like to Be Black and Irish?

“What’s it like to be black and Irish?” “Like a pint of Guinness.” The above quote is taken from an interview with Phil Lynott, the charismatic lead singer of the Celtic rock band Thin Lizzy, on Gay Byrne’s ‘The Late Late Show’. Lynott’s often playful and bold responses to such questions about his identity served to mask his overwhelming feelings of insecurity and ambivalent sense of belonging. As an illegitimate black child brought up in the 1950s in a strict Catholic family in Crumlin, a working-class district of Dublin, Lynott was seen to have a “paradoxical personality” (Bridgeman, qtd. in Thomson 4): his upbringing imbued him “with an acute sense of national and gender identity” (Smyth 39), yet his skin color and illegitimacy made him the target of racial and social abuse in a predominantly white and conservative Ireland. For Lynott, becoming a rockstar offered an opportunity to reinvent himself and be whoever he wanted to be. While he played up to the rock and roll lifestyle in which he was embedded, Lynott is often considered to have been a man trapped inside a caricature (Thomson 301). Geldof (qtd. in Putterford 182) believes that this rocker persona was Lynott’s ultimate downfall and led to his untimely death at just 36 years of age in 1986. For all his swagger and bravado, behind the mask, Lynott was a troubled, young man searching for a place to belong. While many books have been written about the life of Phil Lynott (e.g. Putterford; Lynott; Thomson), few have drawn attention to the notion of identity and the way in which music provided Lynott with an outlet to explore his self. -

Adams Changes with Students by LYN M

Adams changes with students By LYN M. MUNLEY Student priorities are "The students today seem respect for grades — more the jobs are there on a changing, and the man at the to be a more mature group concern about career devel- qualitative basis, and the "heart of the institution," than I've ever seen," Adams opment and placement. Stu- competition is rough," he Frederick G. Adams, is pick- claims, "We don't have the dents seem to be aware of says. ing up the beat. emotional kinds of issues the economic realities of the Another kind of competi- As vice president for that drain our productive country," Adams says. tion, involving student gov- student affairs and services, energies. We can facilitate "People are more concern- ernment officials, worries Adams has his finger on the the learning of the three r's ed about themselves as indi- Adams. "There's a real pulse of the ujniversity. He is much more easily this way.' viduals. Even in dancing problem with the number of in charge of the human After being at UConn for closer together the concern is working hours the officials aspect of UConn's produc- nearly 10 years, first as reflected. It's healthy," he must expend vis a vis com- tion of educated beings. ombudsman, then in the remarks. peting priorities, such as As an individual, Adams school of allied health, then Adams points to what he their academic studies. I exudes an air of idealism, into administrative duty in 60's has turned into the calls a "competitive renais- wish there were some way to optimism and total involve- 1974, Adams has certainly silence of the 70's.