CIVIL ACTION : V. : : EMMANUEL QUIEN, M.D., Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourth District Court of Appeals: 4D17-2141 15 Judicial

Filing # 74015120 E-Filed 06/25/2018 08:48:03 AM IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA Case No. SC18-398 Lower Tribunal No(s).: Fourth District Court of Appeals: 4D17-2141 15th Judicial Civil Circuit: 2016 CA 009672 ALISON RAMPERSAD and LINDA J. WHITLOCK, Petitioners, vs. COCO WOOD LAKES ASSOCIATION, INC. Respondent. PETITION FOR DISCRETIONARY REVIEW OF A DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA, FOURTH DISTRICT PETITIONERS’ AMENDED BRIEF ON JURISDICTION STRICKENPetitioners Represented Propria Persona Filer: Linda J. Whitlock, pro se RECEIVED, 06/25/2018 08:48:29 AM, Clerk, Supreme Court 14630 Hideaway Lake Lane Delray Beach, Florida 33484 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………. i TABLE OF CITATIONS…………………………………………. ii - x PREFACE / INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 1 JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT............................................................ 5 STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS ........................................... 7 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................................................... 8 CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................10 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................................................. 10 CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE ........................................................ 10 STRICKEN Case No. SC2018-398 Amended Jurisdictional Brief Page [ i ] TABLE OF CITATIONS AND AUTHORITIES Supreme Court Cases: Board of City Commissioners of Madison City. v. Grice 438 -

Uniform Trial Court Rules

UNIFORM TRIAL COURT RULES Including Amendments Effective August 1, 2016 (Including Out-of-Cycle Amendments to UTCR 5.100, UTCR Chapter 21 Title, UTCR 21.040, 21.060, 21.070, and 21.100) This document has no copyright and may be reproduced. In the Matter of the Adoption of ) CHIEF JUSTICE ORDER Amendments to the Uniform Trial ) No. 16-019 Court Rules ) ) ADOPTION OF AMENDMENTS TO THE ) UNIFORM TRIAL COURT RULES I HEREBY ORDER, pursuant to ORS 1.002, UTCR 1.030, and UTCR 1.050, the following: 1. The Uniform Trial Court Rules, as amended below, are adopted and are effective August 1, 2016, pursuant to ORS 1.002. 2. All current local rules inconsistent with the Uniform Trial Court Rules as amended will be deemed ineffective on August 1, 2016, pursuant to UTCR 1.030. 3. Local rules that are consistent with the Uniform Trial Court Rules as amended remain in effect and are subject to review as provided under UTCR 1.050. 4. Those local rules that are not amended or repealed and are not disapproved on review under UTCR 1.050 remain in effect until so amended, repealed, or disapproved. Dated this \ 1<lb day of May, 2016. Thomas A. Balmer " Chief Justice IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OREGON In the Matter of the Adoption of ) SUPREME COURT ORDER Amendments to Uniform Trial Court ) No. 16-018 Rule 19.020 ) ) ADOPTION OF AMENDMENTS TO ) UNIFORM TRIAL COURT RULE 19.020 Pursuant to ORS 33.145, the Oregon Supreme Court has approved amendment of Uniform Trial Court Rule (UTCR) 19.020, therefore I HEREBY ORDER the following: 1. -

Vs. Defendant(S) NO. ORDER SETTING

IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF KING NO. NO. Plaintiff(s), ORDER SETTING CIVIL CASE SCHEDULE vs. ASSIGNED JUDGE:_________________ Defendant(s) TRIAL DATE:______________________ (*ORSCS) (*ORSCS) A civil case has been filed in the King County Superior Court and will be managed by the Case Schedule on Page 3 as ordered by the King County Superior Court Presiding Judge. I. NOTICES NOTICE TO PLAINTIFF: The Plaintiff may serve a copy of this Order Setting Case Schedule (Schedule) on the Defendant(s) along with the Summons and Complaint/Petition. Otherwise, the Plaintiff shall serve the Schedule on the Defendant(s) within 10 days after the later of: (1) the filing of the Summons and Complaint/Petition or (2) service of the Defendant's first response to the Complaint/Petition, whether that response is a Notice of Appearance, a response, or a Civil Rule 12 (CR 12) motion. The Schedule may be served by regular mail, with proof of mailing to be filed promptly in the form required by Civil Rule 5 (CR 5). "I understand that I am required to give a copy of these documents to all parties in this case." | Print Name Sign Name ORDER SETTING CIVIL CASE SCHEDULE Revised October 2009 I. NOTICES (continued) NOTICE TO ALL PARTIES: All attorneys and parties shall familiarize themselves with the King County Local Civil Rules [LCR] -- especially those referred to in this Schedule. For example, discovery must be undertaken promptly in order to comply with the deadlines for joining additional parties, claims, and defenses, for disclosing possible witnesses [See LCR 26], and for meeting the discovery cutoff date [See LCR 37(g)]. -

No. 03-1788 ___JOHN D'iorio; DIANE D'iori

PRECEDENTIAL (Filed June 3, 2004) ___________ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT Anthony S. McCaskey, Esq. (Argued) ___________ Peter B. Van Deventer, Jr., Esq. St. John & Wayne No. 03-1788 Two Penn Plaza East ___________ Newark, NJ 07105 Counsel for Appellant JOHN D'IORIO; DIANE D'IORIO Scott K. McClain, Esq. (Argued) v. Winne, Banta, Hetherington & Basralian 25 Main Street MAJESTIC LANES INC., Court Plaza North a New Jersey Corporation, Hackensack, NJ 07602 Counsel for Appellee Appellant ___________ ___________ OPINION OF THE COURT APPEAL FROM THE UNITED ___________ STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT NYGAARD, Circuit Judge. OF NEW JERSEY Under Alternative Dispute Resolution (D.C. No. 01-cv-00809) Act of 1998 (“the Act”), 28 U.S.C. § 651 District Judge: The Honorable et seq., District Courts must enact local Harold A. Ackerman rules authorizing “the use of alternative ___________ dispute resolution processes in all civil actions” in accordance with the Act’s ARGUED MARCH 9, 2004 provisions. 28 U.S.C. § 651(b). The District of New Jersey complied with this Before: SLOVITER and command and enacted N.J. L. Civ. R. NYGAARD, Circuit Judges, and 201.1(h)(1), which reads: OBERDORFER, District Judge* Any party may demand a trial de novo in the District Court by filing with the Clerk a written demand, containing a short and plain *. Hon. Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior statement of each ground in support District Judge, United States District thereof, and serving a copy upon all Court for the District of Columbia, counsel of record or other parties. -

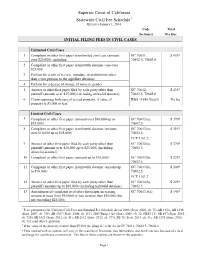

Initial Filing Fees in Civil Cases

Superior Court of California 1 Statewide Civil Fee Schedule Effective January 1, 2014 Code Total Section(s) Fee Due INITIAL FILING FEES IN CIVIL CASES Unlimited Civil Cases 1 Complaint or other first paper in unlimited civil case (amount GC 70611, $ 435* over $25,000), including: 70602.5, 70602.6 2 Complaint or other first paper in unlawful detainer case over $25,000 3 Petition for a writ of review, mandate, or prohibition (other than a writ petition to the appellate division) 4 Petition for a decree of change of name or gender 5 Answer or other first paper filed by each party other than GC 70612, $ 435* plaintiff (amount over $25,000) (including unlawful detainer) 70602.5, 70602.6 6 Claim opposing forfeiture of seized property, if value of H&S 11488.5(a)(3) No fee property is $5,000 or less2 Limited Civil Cases 7 Complaint or other first paper (amount over $10,000 up to GC 70613(a), $ 370* $25,000) 70602.5 8 Complaint or other first paper in unlawful detainer (amount GC 70613(a), $ 385* over $10,000 up to $25,000) 70602.5, CCP 1161.2 9 Answer or other first paper filed by each party other than GC 70614(a), $ 370* plaintiff (amount over $10,000 up to $25,000) (including 70602.5 unlawful detainer) 10 Complaint or other first paper (amount up to $10,000) GC 70613(b), $ 225* 70602.5 11 Complaint or other first paper in unlawful detainer (amount up GC 70613(b), $ 240* to $10,000) 70602.5, CCP 1161.2 12 Answer or other first paper filed by each party other than GC 70614(b), $ 225* plaintiff (amounts up to $10,000) (including unlawful detainer) 70602.5 13 Amendment of complaint or of other first paper increasing GC 70613.5(a) $ 145* amount at issue from $10,000 or less to more than $10,000 (but not exceeding $25,000) 1 Fees pursuant to the Uniform Civil Fees and Standard Fee Schedule Act of 2005 (Stats. -

GS 7A-228 Page 1 § 7A-228. New Trial Before Magistrate

§ 7A-228. New trial before magistrate; appeal for trial de novo; how appeal perfected; oral notice; dismissal. (a) The chief district court judge may authorize magistrates to hear motions to set aside an order or judgment pursuant to G.S. 1A-1, Rule 60(b)(1) and order a new trial before a magistrate. The exercise of the authority of the chief district court judge in allowing magistrates to hear Rule 60(b)(1) motions shall not be construed to limit the authority of the district court to hear motions pursuant to Rule 60(b)(1) through (6) of the Rules of Civil Procedure for relief from a judgment or order entered by a magistrate and, if granted, to order a new trial before a magistrate. After final disposition before the magistrate, the sole remedy for an aggrieved party is appeal for trial de novo before a district court judge or a jury. Notice of appeal may be given orally in open court upon announcement or after entry of judgment. If not announced in open court, written notice of appeal must be filed in the office of the clerk of superior court within 10 days after entry of judgment. The appeal must be perfected in the manner set out in subsection (b). Upon announcement of the appeal in open court or upon receipt of the written notice of appeal, the appeal shall be noted upon the judgment. If the judgment was mailed to the parties, then the time computations for appeal of such judgment shall be pursuant to G.S. -

Local Rules of the Superior Court for Pierce County

PIERCE COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT LOCAL RULES Effective as Amended September 1, 2019 The Local Rules are located on the Pierce County Superior Court website: www.co.pierce.wa.us/superiorcourt ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ TABLE OF RULES ADMINISTRATIVE RULES (PCLR) P. 12 GENERAL RULES (PCLGR) P. 18 CIVIL RULES (PCLR) P. 20 SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS RULES (PCLSPR) P. 40 MANDATORY ARBITRATION RULES (PCLMAR) P. 54 CRIMINAL RULES (PCLCRR) P. 59 ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES P. 60 APPENDIX OF CIVIL RULE FORMS P. 75 ■ADMINISTRATIVE RULES - PCLR 0.1 Citation - Scope 0.2 Court Organization (a) Judicial Departments (1) Judicial Department Location (2) Judicial Department Hours (b) Court Staff (c) Divisions of the Superior Court (1) Juvenile Court (2) Criminal Divisions (3) Civil Divisions 0.3 Court Management (a) Authority (b) Duties - Responsibilities of the Judges of the Superior Court (1) Executive Committee (2) Policies (3) Court Organization (4) Meetings (c) Office of Presiding Judge (1) Duties (2) Selection of Presiding Judge (3) Selection of Assistant Presiding Judge (d) Executive Committee (1) Policy Decisions (2) Policy Recommendations (3) Committees (4) Advisory Capacity (5) Procedure (6) Meetings (7) Selection (8) Unexpired Term 0.4 Commissioners (a) Duties (1) Civil Divisions A, B, C, D, and Ex Parte (2) Juvenile Division (3) Civil Mental Health Division (4) Criminal Division (b) Direction (c) Rotation of Commissioner Duties 0.5 Court Administrator (a) Selection (b) Powers and Duties (1) Administrative (2) Policies (3) Supervisory 2 (4) Budgetary (5) Representative (6) Assist (7) Agenda Preparation (8) Record Preparation and Maintenance (9) Recommendations 0.6 Standing Committees (a) Establishment (b) Selection of Members 0.7 Legal Assistants (a) Authorized Activity (b) Qualifications of Legal Assistant (c) Presentation by Out-of-County Legal Assistants ■ GENERAL RULES – PCLGR 1. -

In the Court of Appeals of the State of Washington Division One

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON DIVISION ONE GARY FILION, ) No. 63978-1-I ) Respondent, ) ) v. ) ) JULIE JOHNSON, ) UNPUBLISHED OPINION ) Appellant. ) FILED: November 22, 2010 ) Ellington, J. — After a mandatory arbitration proceeding, Julie Johnson made a timely request for a trial de novo. The trial court then granted Gary Filion’s motion for a voluntary nonsuit under CR 41(a)(1)(B). On appeal, we agree with Johnson that once the arbitrator filed the award, Filion no longer had the right to dismissal under CR 41(a) without permission. The parties’ remaining contentions are without merit. Accordingly, we reverse the order of dismissal and remand for further proceedings. FACTS Julie Johnson and Gary Filion dissolved their marriage in June 2006. On February 21, 2007, after a dispute over a property distribution provision, Filion filed this action for damages against Johnson, alleging, among other things, negligent infliction of emotional distress and negligent misrepresentation. The case then proceeded to mandatory arbitration. No. 63978-1-I/2 The arbitrator issued an award on February 13, 2009, which was filed in the trial court on March 4, 2009. Johnson requested a trial de novo. On July 29, 2009, the trial court granted Filion’s motion for dismissal under CR 41(a)(1)(B) and dismissed all of his claims without prejudice. DECISION On appeal, Johnson contends the trial court erred in dismissing the case under CR 41(a)(1)(B) because Filion did not move for dismissal before resting in the mandatory arbitration hearing. Filion responds that he had an absolute right to a voluntary dismissal under the plain language of the rule because he had not yet rested his case in the trial de novo. -

Article 90. Appeals from Magistrates and District Court Judges. § 15A-1431

Article 90. Appeals from Magistrates and District Court Judges. § 15A-1431. Appeals by defendants from magistrate and district court judge; trial de novo. (a) A defendant convicted before a magistrate may appeal for trial de novo before a district court judge without a jury. (b) A defendant convicted in the district court before the judge may appeal to the superior court for trial de novo with a jury as provided by law. Upon the docketing in the superior court of an appeal from a judgment imposed pursuant to a plea arrangement between the State and the defendant, the jurisdiction of the superior court over any misdemeanor dismissed, reduced, or modified pursuant to that plea arrangement shall be the same as was had by the district court prior to the plea arrangement. (c) Within 10 days of entry of judgment, notice of appeal may be given orally in open court or in writing to the clerk. Within 10 days of entry of judgment, the defendant may withdraw his appeal and comply with the judgment. Upon expiration of the 10-day period, if an appeal has been entered and not withdrawn, the clerk must transfer the case to the appropriate court. (d) A defendant convicted by a magistrate or district court judge is not barred from appeal because of compliance with the judgment, but notice of appeal after compliance must be given by the defendant in person to the magistrate or judge who heard the case or, if he is not available, notice must be given: (1) Before a magistrate in the county, in the case of appeals from the magistrate; or (2) During an open session of district court in the district court district as defined in G.S. -

Standards of Appellate Review in the Federal Circuit: Substance and Semantics

Standards of Appellate Review in the Federal Circuit: Substance and Semantics Kevin Casey,* Jade Camara** & Nancy Wright*** Introduction “Standards of review” denote the strictness or intensity with which an appellate court evaluates the action of a trial tribunal including, for the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal circuit, a district court judge, a jury, or an agency. At first blush, a discussion of standards of review might appear superficial, or worse, of little consequence. Some might believe that a standard of review is merely a semantic label affixed to a particular issue by an appellate court, and that such labels are virtually irrelevant to the likelihood of success on the merits of an appeal.1 It is tempting to say that standards of review are meaningless rationalizations applied to justify a decision once made. Others might believe that standards of review are obvious: the parties can simply look up the appropriate standards applicable to the issues involved in their 2 particular appeal. Experienced appellate advocates realize, however, that those who frame their appellate practice using such beliefs undermine their chances of obtaining a favorable judgment on appeal. Appellate judges who provide tips almost invariably advise advocates * Kevin R. Casey has B.S. Degrees from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in both Materials Engineering and Mathematics. He received an M.S. Degree in Aerospace-Mechanical Engineering from the University of Cincinnati and worked as an engineer with the General Electric Company. He obtained his J.D. Degree, Magna Cum Laude, from the University of Illinois, where he was Editor-in-Chief of the law review and served for two years as a judicial clerk to The Honorable Helen W. -

CL-2018-3543 Mee Sook Kim V. Giant of Maryland, LLC, Et

NINETEENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OF VIRGINIA Fairfax County Courthouse 4110 Chain Bridge Road Fairfax, Virginia 22030-4009 703-246-2221 • Fax: 703-246-5496 • TDD: 703-352-4139 BRUCE D. WHITE. CHIEF JUDGE COUNTY OF FAIRFAX CITY OF FAIRFAX THOMAS A. FORTKORT RANDY I. BELLOWS JACK B. STEVENS ROBERT J. SMITH J. HOWE BROWN JAN L BRODIE F. BRUCE BACH BRETT A. KASSABIAN M. LANGHORNE KEITH MICHAEL F. DEVINE ARTHUR B. VIEREGG JOHN M. TRAN KATHLEEN H. MACKAY GRACE BURKE CARROLL ROBERT W WOOLDRIDGE. JR. DANIEL E. ORTIZ MICHAEL P. McWEENY PENNEY S. AZCARATE GAYLORD L. FINCH. JR. STEPHEN C. SHANNON STANLEY P. KLEIN THOMAS P. MANN LESLIE M. ALDEN RICHARD E. GARDINER October 4, 2018 MARCUS D. WILLIAMS DAVID BERNHARD JONATHAN C. THACHER DAVID A. OBLON CHARLES J. MAXFIELD DENNIS J. SMITH JUDGES LORRAINE NORDLUND DAVID S. SCHELL Bhavik D. Patel, Esquire RETIRED JUDGES MACDO WELL LAW GROUP, P.C. 10500 Sager Avenue, Suite F Fairfax, VA 22030 bdp(w,lawmacdowell.corn Counsel for Mee Sook Kim Kathryn L. Harman, Esquire SEMMES, BOWEN, SEMMES, PC 1577 Spring Hill Road, Suite 200 Vienna, VA 22181 kharrnansemmes.corn Counsel for Defendant Giant of Maryland, LLC Richard L. Butler, Esquire LAW OFFICES OF JONATHAN P. JESTER 4480 Cox Road, Suite 225 Glen Allen, VA 23060 Richard.butler@,thechartford.corn Counsel for Defendant Union Mills Associates, LP Michael Thorsen, Esquire BANCROFT, MCGAVIN, HORVATH, JUDKINS, P.C. 9990 Fairfax Boulevard, Suite 400 Fairfax, VA 22030 mthorscn(a;bmhjlaw.com Counsel for Defendant Rappaport Management Company Re: Mee Sook Kim v. Giant of Maryland, LLC, et al. -

SUPERIOR COURT of CALIFORNIA COUNTY of LOS ANGELES -Vii- CHAPTER Three CIVIL DIVISION RULES 43 3.1 APPLICABILITY

SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES CHAPTER Three CIVIL DIVISION RULES 43 3.1 APPLICABILITY ...........................................................................................43 GENERAL PROVISIONS ..............................................................43 3.2 ASSIGNMENT OF CASES ...........................................................................43 3.3 ASSIGNMENT OF DIRECT CALENDAR CASES .....................................43 (a) Proportionate Assignment .....................................................................43 (b) Regulation of Case Assignment ............................................................43 (c) Notice of Case Assignment ...................................................................43 (d) Improper Refiling ..................................................................................43 (e) Duty of Counsel .....................................................................................43 (f) Related Cases .........................................................................................44 (g) Consolidation of Cases ..........................................................................44 (h) Coordination of Non-Complex Cases ....................................................44 (i) Assignment for All Purposes .................................................................44 (j) Effect of Judge Unavailability ...............................................................45 (k) Complex Litigation ................................................................................45