Appendices Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

oRAGNET ·THE DAILY ··NEWS MOZART 1,.\NUARY • 21, 22, available al 23. 24, 25, 26 ~~· Vol. 64. No. 18 ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, TUESDAY, JANUARY 22/1957 (Price .5 cents) Charles Hutton & Sons. - ~----------------·--~--------·----------~---------------------------------·----------------------------~----~~~~~---------- Of larva .. Debate On ·oristructio·n roup irited .' .. • eechl From Throne' oustn , , ;· - r::crtion-hrr·llhc Conscrvatil"es around theil· : assistance for rcdcl"eloping !bCU" 0 osts 1 1 I ' .. ·.' . · , .'·Jf,rll m the motion's claim that tb~ govcJ\i·! won1out areas. · i• ·• · ... I ment has lost the confidcuc~ I REDEVELOP SLUliiS ' -----------~--..._,.;---------.....:....----------- ··:·. ;,, ·:\- ;, c bunched a of Parliament and the conntr1· 'I The National Housing Act pro- .::";,· . f •nnrt· CC'Frr, through its "incliffercncc, inerli:t, ·vidcd that the federal SOI'~rn- - ·. ,. ,, Hn11 tiryin;: i and lack of leadership." 1 ment, through its Central :llort- Help' Lower . · .... , ·' :1 he tr:·in~ i The ''cxtr:wr1iinary" t h i •i r: · gng~ and Housing Corporation, . _ '· , · p.,rty mal·~·· , about this "is that in fact tb~ I would share costs of sturlying • :1 ..~ 1 .. , . :. 111 !he next i only group lu this House to whicll 1 municipal areas for redevelop. _- , .·., , · ,:,llHiay .•Tun~ tho<c words Ci\n be properly as· , mcnt. It also would split costs · . .• ,, dwt:.~nt:r'i I crihcd is the official OJ1position: ol acquiring R\111 clearing such Income Groups .. ' 1: • , · 1;.miin~r 10 , Thi~ had been particularly nJl· 1areas, either on a fcdcrnl-prov- • 1!w ~o1·crn· ' parent when Opposition Leaer . ineial-munlcipnl basis or, with TORONTO (CP) - The Canadian Construction .1;:riculture ! Dtrfcnh:~k·~r. in re;:nril to the rcc· 1 prol'incial approval, directly with r.i\ CPR firemen's strike, said I the munlcipa!lly. -

The Persecution of Doctor Bodkin Adams

THE PHYSICIAN FALSELY ACCUSED: The Persecution Of Doctor Bodkin Adams When the Harold Shipman case broke in 1998, press coverage although fairly extensive was distinctly muted. Shipman was charged with the murder of Mrs Kathleen Grundy on September 7, and with three more murders the following month, but even then and with further exhumations in the pipeline, the often scurrilous tabloids kept up the veneer of respectability, and there was none of the lurid and sensationalist reporting that was to accompany the Soham inquiry four years later. It could be that the apparent abduction and subsequent gruesome discovery of the remains of two ten year old girls has more ghoul appeal than that of a nondescript GP who had taken to poisoning mostly elderly women, or it could be that some tabloid hacks have long memories and were reluctant to jump the gun just in case Shipman turned out to be another much maligned, benevolent small town doctor, for in 1956, a GP in the seaside town of Eastbourne was suspected and at times accused of being an even more prolific serial killer than Harold Shipman. Dr Bodkin Adams would eventually stand trial for the murder of just one of his female patients; and was cleared by a jury in less than three quarters of an hour. How did this come about? As the distinguished pathologist Keith Simpson pointed out, the investigation into Dr Adams started as idle gossip, “a mere whisper on the seafront deck chairs of Eastbourne” which first saw publication in the French magazine Paris Match - outside the jurisdiction of Britain’s libel laws. -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

The London Gazette J3ublfs!)Tti

41171 . 5287. The London Gazette J3ublfs!)tti Registered as a Newspaper For Table of Contents see last page TUESDAY, 10 SEPTEMBER, 1957 Treasury Chambers, S.W.I. LONDON HACKNEY CARRIAGE ACT, 1&50. The Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty's CAB STANDINGS. Treasury 'hereby give notice ithat They have made Notice is hereby given that in pursuance of sec- an Order under section 119 of the Import Duties Act, tion 4 of the London Hackney Carriage Act, 18'50, 1932, section 7 of 'the Finance Act, 1934 and section 1 the Commissioner of 'Police of the Metropolis has of .the Import Duties (Emergency Provisions) Act, issued 'Orders appointing the following caib 1939, viz.:— standings:— The Import Duties (Drawback) <iNo. 15) Order Orders dated 3\lst May, 1957. 1957, which revokes certain obsolete provisions . A standing for two hackney carriages at Sloane allowing drawback of Customs duty. Avenue (Fulham Road), S.W. The Order comes into operation on the 14tih A standing for three hackney carriages at Aber- September, 1957 and has been published as Statutory conway Road, Morden, Surrey. Instruments 1957, No. 1588. A standing for eleven hackney carriages at Copies may be purchased (price 3d. net) direct from Victoria Road. South Ruislip, Middlesex. Her Majesty's Stationery Office at the addresses shown on the last page >of this Gazette or through Orders dated l!Tth June, 1957. any bookseller. A standing for thirteen hackney carriages at Piccadilly (Down Street), W., in two portions. A standing for three hackney carriages at Arling- ton Street (iBennet Street), Westminster, S.W. Whitehall, l&th September, 1957. -

We Should Disregard International Banking Influence in the Pursuit of Our Congressional Monetary Policy.”

Presented © January 2011-2017 by Charles Savoie An Initiative to Protect Private Property Rights of American Citizens “A GIGANTIC CONSPIRACY WAS FORMED IN LONDON AND NEW YORK TO DEMONETIZE SILVER” ---Martin Walbert, “The Coming Battle—A Complete History of the National Banking Money Power in the United States” (1899) "A Secret Society gradually absorbing the wealth of the world." --- Last Will & Testament of diamond monopolist Cecil Rhodes “HERE AND EVERYWHERE” ARE YOU INTERESTED IN PROTECTING YOUR OWNERSHIP RIGHTS IN PRECIOUS METALS? THEN PLEASE READ THIS, TAKE WEEKS TO CHECK OUT THE DOCUMENTATION IF YOU DISPUTE IT, AND DO EVERYTHING YOU CAN TO ENCOURAGE THE WIDEST POSSIBLE READERSHIP FOR IT! THIS MEPHISTOPHELES AND HIS ASSOCIATES AND SUCCESSORS MUST BE STOPPED FROM USING THE PRESIDENT TO SEIZE SILVER AND GOLD! (There is no Simon Templar halo over his head!) Ted Butler, the most widely followed silver commentator, has often said to buy and hold physical, because that puts you beyond COMEX rule changes. That’s correct! However, there remains an immeasurably more insidious, far reaching entity that can change rules---Uncle Sam, and he’s tightly in the grasp of the same forces who’ve depressed silver for generations. Uncle Sam nationalized gold and silver in the Franklin Roosevelt administration; this is subject to a repeat! Now that the price can’t be suppressed, what’s next? FORBID OWNERSHIP! You have hours for professional sports and TV talk shows; how about some time for your property rights, without which you can go broke? Whether the excuse cited is North Korea, the Middle East or other, the actual reason is to break us and prevent capital formation on our part! Please read and act on what follows--- ******************************************************************* *** “What an awful thought it is that if we had not lost America, or if even now we could arrange with the present members of the United States Assembly and our House of Commons, the peace of the world is secured for all eternity. -

MOWER Rose' Union Funds Used for Girl's New

-J: ■ j*.-- ^ 4 ' ‘■'Ai TT-^ ;■ . ..y. _---- Ja... ■ __ : • i. V 77-*V— ^7' _ £■ £ '■>S' £■ •44- 'A ': •• 1 V:/, . IvJ ■/ -V'd: V" , - WEDNESDAY, MARCH 20,''] ATerag6 Daily PreKk itan r 'if / V Tli« Weatlier ' 'PAGE*TWENTY.l!^UR Foir tke Wow Ended j ' ForeMst of ^U. 8. Woather Bureau dlatttl)pjater SttEtting l|m U i March 16, 1967 If . ' ' nUr 8nd colder tonight. Low of Mrs. Donald Harrison. 16 Reared Heart Mothara arele 12,647 will meet Tbureday at 8 p.m.. at 25-^. FHdny fmlr nad oomeHiiot Griswold St. Plans were made to M M HDrive Member of the Audit wOrmor. High In the \&y/et 508. « About Town attend the Holy Day of- Recollec the honva. of Mra. Thomaa Heaiy. Bureau of Oirc.ulatlod ■ • ■ . ■' ■ ■■ 1 ■ ■ tion at the Cenacle in Middletown 77 Concord Rd. f'Ti You asked for ihedt ManchesleP— A City of Village Charm March 28 and the Holy Family A t|7 2 4 ,1 8 6 •n» Holy Ohoit Mothofi Circle Monastery in Farmlnfton Aprll^lO. Grace Group of the Centdr Con - ^ n d , here the^ last nlglit attended Mlaa Mildred gregational Church will hold a B o w ^ talk on converalon, apon- Steadily inching toward its are! ;^OL. LXXVl, NO. 14$ . (TWENTY-FOUR PAGESf-TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY," MARCH 21, 19$7 (iblaeslfled Adrerttsing on Page 62)' PRICE FIVE CElifTS AU members Of St.- Bridget's aprlnt food aale at tha J. W. Hale aored Gibbons Assembly, Store Saturday, starting at 10 a.m. initial goal of 6860.000,'lha Man ■ ^ .r. -

Books on Serial Killers

_____________________________________________________________ Researching the Multiple Murderer: A Comprehensive Bibliography of Books on Specific Serial, Mass, and Spree Killers Michael G. Aamodt & Christina Moyse Radford University True crime books are a useful source for researching serial killers. Unfortunately, many of these books do not include the name of the killer in the title, making it difficult to find them in a literature search. To make researching serial killers easier, we have created a comprehensive bibliography of true crime books on specific multiple murderers. This was done by identifying the names of nearly 1,800 serial killers and running searches of their names through such sources as WorldCat, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and crimelibrary.com. This listing was originally published in 2004 in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology and was last updated in August, 2012. An asterisk next to a killer’s name indicates that a timeline written by Radford University students is available on the Internet at http://maamodt.asp.radford.edu/Psyc%20405/serial_killer_timelines.htm and an asterisk next to a book indicates that the book is available in the Radford University library. ______________________________________________________________________________________ Adams, John Bodkin Devlin, Patrick (1985). Easing the passing. London: Robert Hale. (ISBN 0-37030-627-9) Hallworth, Rodney & Williams, Mark (1983). Where there’s a will. Jersey, England: Capstans Press. (ISBN 0-946-79700-5) Hoskins, Percy (1984). Two men were acquitted: The trial and acquittal of Doctor John Bodkin Adams. London: Secker & Warburg (ISBN 0-436-20161-5) Albright, Charles* *Matthews, John (1997). The eyeball killer. NY: Pinnacle Books (ISBN 0-786-00242-5) Alcala, Rodney+ Sands, Stella (2011). -

JCC DONATES NEW DIGITAL SCOREBOARD to GROVE Park

The The Magazine of the City of London School alumni association: the John Carpenter Club Carpenter John School alumni association: the City of London The Magazine of the Issue 307 JCC DONATES NEW DIGITAL SCOREBOARD TO GROVE PARK Autumn 2013 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Editorial Wednesday 20 November 2013 My first year at City is now over. Nevertheless, despite the Notice of AGM welcoming nature The Annual General Meeting of the Club will be held in the Asquith Room of the people here, at the School on Wednesday 20 November 2013 at 6:00pm, this institution seems to inspire preceded by tea from 5:30pm. such staying power that it takes many years to no longer be considered a Agenda newbie! The valetes on pages 10-13 are 1. Apologies for absence. testament to this, as they document 130 years of service to the School between 2. Minutes of last meeting (21 November 2012). them. Many of the staff who come to 3. Correspondence. City choose to stay. Of course, the pupils don’t get a choice - once Senior 4. Finance: to receive the Club Accounts for the year ended 30 April 2013 Sixth is completed, you’re out! We do of 5. To receive the Report of the General Committee for the year 2012/2013. course hope you’ll want to continue your A copy of the Accounts and of the Report may be inspected at the Reception relationship with City, though. There are desk at the School in the week before the meeting. Copies will also be sent to numerous ways you can do this: perhaps any member before the meeting upon application to the Treasurer and Secretary you could give careers advice to a current respectively. -

MOMENT RESUME In.% A

MOMENT RESUME BD '154 415 CS X04 151 . .., . AbTHOR Kraus, V. Keith . 0 TITLE 'Murder, Mischief, ant Mayhem: A Process for Creative --A . , Research Papers. INSTITUTXON National Council of TeacherS of.:English, Urbana, In.% A PUB DATE 78 .; NOTE . 148p. AVAILABLE .FROM National Council of Teachers'of English, 1111'Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 4Stock No. 32200, $5,95 non-member, $4.70 member) EDRS PRICE MF-i0.83 HC -$7.35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS' College Freshmen;'*Composition°(Liteary); English Instruction; *Expository Vritim; Higher Education;' Information Seeking; Inforatien UtilizatiOn;. *Learning Activ'iti'es; Library Research; *Libpry Skills; *Research Projects; *Research:Skills; Writing 1 Skills IDENTIFIERS *Research Papers .9' ABSTRACT . Assuming thatNfreshman research papers can ble r-r-- interesting as well as educational, this book presents tensample student, papers selected from classes in which research methods were taught through the use of newspapers and periodicals. The paper topics, based on real people and actual events, range from bizaare, murder cases and treasure expeditions to famous Indians, explorers, and obscure biographies. In addition to the student papers, the book offers the foiloWing guidelines for researching and writing aboit a newpaper case: library research exercises, methods' for'research, a -procedure for writing a paper, and a ten-point research.paper check 'list, for students. The book includes a list of 100 annotated research. topics that have resulted in superlot-studenipaperi over a five year teaching period. (MAI) , 4 1 ,) t - , . , . , . ***********************************************************************-0' * 'Reproductions supplied by:EDRS are the best that can, be made 0 , * . from the original document. Alt, 4c#44,11*#211****4444404421144#44214#######*2011444421421120001441214#2114420000444401421444 v ti U S. -

Daily Express

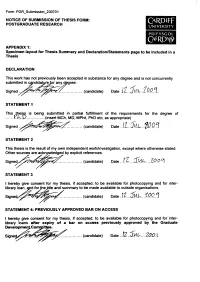

Form: PGR_Submission_200701 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF THESIS FORM: POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH Ca r d if f UNIVERSITY PRIFYSGOL CAERDVg) APPENDIX 1: Specimen layout for Thesis Summary and Declaration/Statements page to be included in a Thesis DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in capdidatyrefor any degree. S i g n e d ................. (candidate) Date . i.L.. 'IP .Q . STATEMENT 1 This Thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Y .l \.D ..................(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed (candidate) Date .. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Sig (candidate) Date STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, apd for thefitle and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signe4x^^~^^^^pS^^ ....................(candidate) Date . STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Graduate Developme^Committee. (candidate) Date 3ml-....7.00.1 EXPRESSIONS OF BLAME: NARRATIVES OF BATTERED WOMEN WHO KILL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY DAILY EXPRESS i UMI Number: U584367 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Medico-Legal Think the Addiction Would Have Reached the Degree to Which the Doctors Would Have to Give Any Attention to Gradually Weaning

BRIATsIH ~~~~~~~~~v~~~~~~~~~~~~~~MEDICALAPRIL 13, 1957JouR-NAL.OBITUARY 889 Navy until 1919, his wartime duties taking him to China, be possible that she could have survived what was then among other places. He acted for a short time as medical more than 12 times as much; the dosage had been raised officer to the Canton municipal council, later becoming 18 times after only six days, and he did not think it was medical officer to the Dimbulla District Planters' Associa- possible that a woman of 80 could survive that. tion in Ceylon. In 1928 he returned to England and joined He said that every general practitioner would be aware of the late Sir Stewart Abram in partnership at Reading. On such facts in relation to morphia, because it was a drug of the death of his partner, Dr. Price carried on the practice almost universal use. Not quite the same could be said of alone until 1947, when he was joined by his son, Dr. heroin, because there must be many family doctors who H. M. Price. For some time Dr. Price was in charge of virtually never used it except perhaps in a linctus. He had the physiotherapy department of the Royal Berkshire Hos- never himself used heroin and morphia together in condi- pital, where previously he had been clinical assistant in the tions where there was not severe pain, nor had he seen it ear, nose, and throat department for 13 years. He was used by a colleague in such circumstances. medical officer to Reading School and commanding officer He said that the complaint of severe pain on June 27, and medical officer from 1943 to 1946 of the Reading Sea 1948, when the patient had been at the Neston Cottage Cadet Corps. -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc.