Investigating the Murder File: a Biographical Analysis of Creation, Survival and Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

oRAGNET ·THE DAILY ··NEWS MOZART 1,.\NUARY • 21, 22, available al 23. 24, 25, 26 ~~· Vol. 64. No. 18 ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, TUESDAY, JANUARY 22/1957 (Price .5 cents) Charles Hutton & Sons. - ~----------------·--~--------·----------~---------------------------------·----------------------------~----~~~~~---------- Of larva .. Debate On ·oristructio·n roup irited .' .. • eechl From Throne' oustn , , ;· - r::crtion-hrr·llhc Conscrvatil"es around theil· : assistance for rcdcl"eloping !bCU" 0 osts 1 1 I ' .. ·.' . · , .'·Jf,rll m the motion's claim that tb~ govcJ\i·! won1out areas. · i• ·• · ... I ment has lost the confidcuc~ I REDEVELOP SLUliiS ' -----------~--..._,.;---------.....:....----------- ··:·. ;,, ·:\- ;, c bunched a of Parliament and the conntr1· 'I The National Housing Act pro- .::";,· . f •nnrt· CC'Frr, through its "incliffercncc, inerli:t, ·vidcd that the federal SOI'~rn- - ·. ,. ,, Hn11 tiryin;: i and lack of leadership." 1 ment, through its Central :llort- Help' Lower . · .... , ·' :1 he tr:·in~ i The ''cxtr:wr1iinary" t h i •i r: · gng~ and Housing Corporation, . _ '· , · p.,rty mal·~·· , about this "is that in fact tb~ I would share costs of sturlying • :1 ..~ 1 .. , . :. 111 !he next i only group lu this House to whicll 1 municipal areas for redevelop. _- , .·., , · ,:,llHiay .•Tun~ tho<c words Ci\n be properly as· , mcnt. It also would split costs · . .• ,, dwt:.~nt:r'i I crihcd is the official OJ1position: ol acquiring R\111 clearing such Income Groups .. ' 1: • , · 1;.miin~r 10 , Thi~ had been particularly nJl· 1areas, either on a fcdcrnl-prov- • 1!w ~o1·crn· ' parent when Opposition Leaer . ineial-munlcipnl basis or, with TORONTO (CP) - The Canadian Construction .1;:riculture ! Dtrfcnh:~k·~r. in re;:nril to the rcc· 1 prol'incial approval, directly with r.i\ CPR firemen's strike, said I the munlcipa!lly. -

UNIVERSITY of WINCHESTER the Post-Feeding Larval Dispersal Of

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER The post-feeding larval dispersal of forensically important UK blow flies Molly Mae Mactaggart ORCID Number: 0000-0001-7149-3007 Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work Copyright © Molly Mae Mactaggart 2018 The post-feeding larval dispersal of forensically important UK blow flies, University of Winchester, PhD Thesis, pp 1-208, ORCID 0000-0001-7149- 3007. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the author. Details may be obtained from the RKE Centre, University of Winchester. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. No profit may be made from selling, copying or licensing the author’s work without further agreement. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr Martin Hall, Dr Amoret Whitaker and Dr Keith Wilkinson for their continued support and encouragement. Throughout the course of this PhD I have realised more and more how lucky I have been to have had such a great supervisory team. -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 7 Territorial Boundaries This may seem a superfluous title for an eponymous society, so a few words of explanation are thought necessary. The Society’s sometime reluctance to expand its interests beyond the city boundary has not prevented a more elastic approach when the situation demands it. Indeed it is not true that the Society has never been prepared to look beyond the City boundary. As early as 1971 the committee expressed a wish that the Society might be a pivotal player in the formation of amenity bodies in the surrounding districts. It was resolved to ask Sir Frank Pearson to address the Society on the issue, although there is no record that he did so. When the Society was formed, and, even before that for its predecessor, there would have been no reason to doubt that the then City boundary would also be the Society’s boundary. It was to be an urban society with urban values about an urban environment. However, such an obvious logic cannot entirely define the part of the city which over the years has dominated the Society’s attentions. This, in simple terms might be described as the city’s historic centre – comprising largely the present Conservation Areas. But the boundaries of this area must be more fluid than a simple local government boundary or the Civic Amenities Act. We may perhaps start to come to terms with definitions by mentioning some buildings of great importance to Lancaster both visually and strategically which have largely escaped the Society’s attentions. -

3Rd ANNIVERSARY SALE GOOLERATOR L. T.WOOD Co

iOandtralnr Evntittg BATUBDAT, KAY 9 ,19M. HERAlXf COOKING SCHOOL OPENS AT 9 A, M . TOMORROW AVBBAQB DAILT OIBOUtATION THU WKATHBB tor the Month of April, I9S6 Foreeaat of 0 . A Wenthm Banaa. 10 CHICKENS FREE Get Your Tickets Now 5,846 Raitford Forth* Mwtnher o f tha Andlt MoMly ahmdr tanltht and Tnea- t Esoh To Fir* Lnoky Peneas. T» B* Dnwa tetortef, Maj ASPARAGUS Bnrann of OIrcnIatlona. day; wajiner tonight. 9th. MANfiiHfeSTER - A CITY OF VILLAGE CHARM No String* APnched. tm t Send In Thla Oonpon. Eighth Annual Concert VOL. LV., NO. 190. (Cllaailtled AdvettlslBS on Pago ld .| , (SIXTEEN PAGES) POPULAR MARKET MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY. MAY 11,1936. PRICE THREE CENTS BnMnoff IMUdlng of th* Louis L. Grant Buckland, Conn. Phone 6370 COOKING SCHOOL OHIO’S PRIMARY As Skyscrapers Blinked Greeting To New Giant of Ocean Airlanes G CLEF CLUB AT STATE OPENS BEING WATCHED MORGENTHAU CALLED Wednesday Evening, May 20 TOMOR^W AT 9 A S T R ^ G U A G E at 8 O'clock IN TAX BILL INQUIRY 3rd ANNIVERSARY SALE Herald’s Aranal Homemak- Borah Grapples M G. 0. P. Treasory’ Head to Be Asked Emanuel Lutheran Church ing Coarse Free to Wom- Organization, CoL Breck Frazier-Letnke Bill to Answer Senator Byrd’s Snbocription— $1.00. en -^ s Ron Each Morning inridge Defies F. D. R. in Is Facing House Test Charge That hroTisions of -Tkrongfa Coming Friday. BaHotmg; Other Primaries Washington, May II.—(AP) ^floor for debate. First on toe sched House Bin Would P em ^ —Over the opposition of ad- ule was a House vote on whether to The Herald'a annual Cooking Washington, May 11.— (A P ) — mlnlBtration leaders, the House discharge the rules committee from ■ehool open* tomorrow morning at Ohio’s primary battleground — to voted 148 to 184 In a standing consideration uf a rule permitting Big Corporations to Evade 9 o’clock in the State theater. -

The Times , 1992, UK, English

. 1 8 INTERNATIONAL j \ EDITION 45 p Finance ministers ODAY IN turnon 1pTJHE TIMES Delors OPEN DAY From George Brock rm IN LUXEMBOURG EC FINANCE ministers Iasi night fired a relentless bar- rage of criticism and com- - plaint at Jacques Delors proposals to boosr the Euro- pean Community’s budget by 30 per cent — at a time when most of Europe's treasuries are tightening their bells. The ministers enjoyed their first opportunity to lay into the ambitious plans laid earli- er this year by rhe French The Duke of Kent president of the European leads Britain's Commission. The Danish ref- Freemasons who are erendum has altered the com- doing their bit for plexion of every one of the hundreds of weekly Commu- glasnost nity meetings. An embold- Life <& Times ened Danish fishing minister Page I yesterday asked for a larger quota of sole for his country's fishermen. In another pan of OPEN the building, the finance min- isters scented blood. The DOOR blood belongs to M Delors. i ’ in KiHfttinier " 1 The discussion, one of his aides admitted, was *'a little Summit guard: Brazilian troops looking out for trouble from the cable car station on top of the Sugar Loaf mountain in Rio de Janeiro rough". M Delors is bound by the Community’s hasty consensus that the Danes' re- jection of the Maastricht trea- Watchdog ty can safely be ignored. Yesterday, adjusting only a isolated few Heseltine figures Bush as UK to take account of orders BT a recent deal to reform the backs mines common agricultural policy. -

The Persecution of Doctor Bodkin Adams

THE PHYSICIAN FALSELY ACCUSED: The Persecution Of Doctor Bodkin Adams When the Harold Shipman case broke in 1998, press coverage although fairly extensive was distinctly muted. Shipman was charged with the murder of Mrs Kathleen Grundy on September 7, and with three more murders the following month, but even then and with further exhumations in the pipeline, the often scurrilous tabloids kept up the veneer of respectability, and there was none of the lurid and sensationalist reporting that was to accompany the Soham inquiry four years later. It could be that the apparent abduction and subsequent gruesome discovery of the remains of two ten year old girls has more ghoul appeal than that of a nondescript GP who had taken to poisoning mostly elderly women, or it could be that some tabloid hacks have long memories and were reluctant to jump the gun just in case Shipman turned out to be another much maligned, benevolent small town doctor, for in 1956, a GP in the seaside town of Eastbourne was suspected and at times accused of being an even more prolific serial killer than Harold Shipman. Dr Bodkin Adams would eventually stand trial for the murder of just one of his female patients; and was cleared by a jury in less than three quarters of an hour. How did this come about? As the distinguished pathologist Keith Simpson pointed out, the investigation into Dr Adams started as idle gossip, “a mere whisper on the seafront deck chairs of Eastbourne” which first saw publication in the French magazine Paris Match - outside the jurisdiction of Britain’s libel laws. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

CHESHIRE COUNTY AA CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2003 Vauxhall Motors Sports & Social Club, Ellesmere Port, Sunday 5 January 2003

CHESHIRE COUNTY AA CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2003 Vauxhall Motors Sports & Social Club, Ellesmere Port, Sunday 5 January 2003 Senior/Veteran Men (10.2 km) 1 Nick Jones Tipton 34:30 73 Martin Rands Macclesfield 47:23 2 Bashir Hussain Stockport 35:07 74 39 Geoff Hand V45 Spectrum Striders 47:25 3 Matt Lockett Univ Birmingham 35:27 75 40 Colin Rathbone V55 Vale Royal 47:45 4 Matt Barnes Altrincham 35:49 76 41 Roy Tunstall V60 Helsby 47:54 5 Ian Salisbury Trafford 35:53 77 42 Dave Ratcliffe V55 Tattenhall 47:59 6 Tom Carter Vale Royal 36:25 78 43 Brian Hastings V55 West Cheshire 48:21 7 Peter Benyon City of Stoke 37:05 79 44 A Peers V60 Spectrum Striders 48:34 8 Andrew Maudsley City of Stoke 37:29 80 45 Dave Hough V50 West Cheshire 49:16 9 Malcolm Fowler Wilmslow(n/s) 37:36 81 46 Ian Hilditch V60 Helsby 49:25 10 1 Tom McGaff V45 Wilmslow 37:40 82 47 Mark Wheelton V40 Macclesfield 49:42 11 David Barker Thames H&H 37:41 83 48 Dave Spencer V50 Warrington 50:14 12 Duncan Bell West Cheshire 37:59 84 49 Bill Vinton V50 West Cheshire 50:56 13 2 Mike Weedall V45 Vale Royal 38:05 85 Mark Lee Hearn West Cheshire 51:30 14 3 Graham MacNeil V40 Helsby 38:08 86 50 Rich Benson V50 Congleton 51:34 guest Steve Millward City of Sheffield 38:10 87 51 A Smith V40 Helsby 52:07 15 4 Les Brookman V45 Warrington 38:15 88 52 Mike Lamb V60 West Cheshire 52:22 16 C Southern Spectrum Striders 38:32 89 53 Chris Lamb V50 Tattenhall 52:42 17 N Crompton Warrington 38:52 90 54 Lawrie Woodley V65 Tattenhall 53:13 18 Gavin Tomlinson Sale H Manchester 39:12 91 55 Richard -

A Veritable Revolution: the Court of Criminal Appeal in English

A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS B.A. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1986 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 CECILE ARDEN PHILLIPS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A VERITABLE REVOLUTION: THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEAL IN ENGLISH CRIMINAL HISTORY 1908-1958 Cecile Arden Phillips, Candidate for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In a historic speech to the House of Commons on April 17, 1907, British Attorney General, John Lawson Walton, proposed the formation of what was to be the first court of criminal appeal in English history. Such a court had been debated, but ultimately rejected, by successive governments for over half a century. In each debate, members of the judiciary declared that a court for appeals in criminal cases held the potential of destroying the world-respected English judicial system. The 1907 debates were no less contentious, but the newly elected Liberal government saw social reform, including judicial reform, as their highest priority. After much compromise and some of the most overwrought speeches in the history of Parliament, the Court of Criminal Appeal was created in August 1907 and began hearing cases in May 1908. A Veritable Revolution is a social history of the Court’s first fifty years. There is no doubt, that John Walton and the other founders of the Court of Criminal Appeal intended it to provide protection from the miscarriage of justice for English citizens convicted of criminal offenses. -

May 18 Web.Pub

CHALLENGE The Parish Magazine of St Mary’s Sandbach May 2018 Volume 54 No 636 May 2018 Sunday 6th May 8.00 am Holy Communion 6 Easter 10.00 am Morning Worship 6.30 pm Holy Eucharist Thursday 10th May 7.30 pm Holy Communion at Accession Day St john's Sandbach Heath Sunday 13th May 8.00 am Holy Communion 7 Easter 10.00 am Parish Eucharist 6.30 pm Evensong Sunday 20th May 8.00 am Holy Communion Pentecost 10.00 am Parish Eucharist 6.30 pm Churches Together in Sandbach Service Sunday 27th May 8.00 am Holy Communion Trinity Sunday 10.00 am Parish Eucharist 6.30 pm Choral Evensong Sunday 3rd June 8.00 am Holy Communion 1 Trinity 10.00 am Morning Worship 6.30 pm Holy Eucharist Every Wednesday 11.00 am Holy Communion Holy Eucharist, Parish Eucharist = Order 2 Common Worship Holy Communion = Order 1 Book of Common Prayer 1 erhaps we don't need there only because of the P reminding that St Mary's has generosity of those who support it. been in Sandbach for over 1000 As we know there are no years. Its foundation date is not government grants, no money known so the anniversary of the from central church funds to keep laying of the foundation stone will it going and only a very small pass us by with no ceremony. proportion of these costs come One of the great features of from fees charged for, weddings English life is the presence of the and funerals. The church is here parish church at the heart of any today because of the generosity of community. -

Download PDF Version

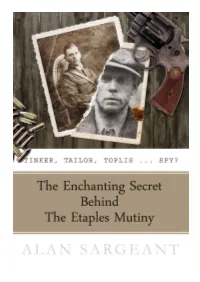

The newspaper lying on the windowsill of the bothy said it all really: ‘Enchanting Secret Behind …’ Behind what? We may never know. Whether it was a deliberate move to preserve the spirit of a beautifully enduring mystery, or the fear of terminating some dream or hope that continues to sit loaded in my imagination like the pistol used in Percy’s getaway, I never did unfold the paper to reveal how the headline concluded. It probably sits there now, a taunting reminder of all we may never know about Toplis and the Mutiny in Etaples that this wily, cocky brigand may or may not have played a part in. Facts are scarce when it comes to Percy. He first entered the public consciousness in 1920 when for a brief spell he was the most wanted war deserter in England, tried and found guilty in absentia for the murder of taxi-driver, Sidney Spicer before being ambushed and gunned-down in Cumbria. 50 years later he was resurrected — this time as the hero of Bill Allison and John Fairley’s book, The Monocled Mutineer which painted a harsh and uncompromising picture of the riots that took place at the Etaples Training Ground in September 1917. He was and remains part-media creation, a patchwork of ideals and projections, a man fashioned from the slag of other men’s aspirations, a hero among unheroes, a cautionary tale derived from a less than cautious history. Anarchist? Activist? Spy? Violent criminal? I stroked my fingers over the moisture that a cooler, airish morning had left on the bothy window and signed it ‘Percy’.