An Analysis of Syncretic Culture in Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu)

Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF MODERN INDIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERARY STUDIES (Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu) UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMME (Courses effective from Academic Year 2015-16) SYLLABUS OF COURSES TO BE OFFERED Core Courses, Elective Courses & Ability Enhancement Courses Disclaimer: The CBCS syllabus is uploaded as given by the Faculty concerned to the Academic Council. The same has been approved as it is by the Academic Council on 13.7.2015 and Executive Council on 14.7.2015. Any query may kindly be addressed to the concerned Faculty. Undergraduate Programme Secretariat Preamble The University Grants Commission (UGC) has initiated several measures to bring equity, efficiency and excellence in the Higher Education System of country. The important measures taken to enhance academic standards and quality in higher education include innovation and improvements in curriculum, teaching-learning process, examination and evaluation systems, besides governance and other matters. The UGC has formulated various regulations and guidelines from time to time to improve the higher education system and maintain minimum standards and quality across the Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) in India. The academic reforms recommended by the UGC in the recent past have led to overall improvement in the higher education system. However, due to lot of diversity in the system of higher education, there are multiple approaches followed by universities towards examination, evaluation and grading system. While the HEIs must have the flexibility and freedom in designing the examination and evaluation methods that best fits the curriculum, syllabi and teaching–learning methods, there is a need to devise a sensible system for awarding the grades based on the performance of students. -

The Book Collection of Artist and Educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) Courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

YMeDaCa: READING LIST The book collection of artist and educator Philip Rawson (1924-1995) courtesy of the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park. With special thanks to NAEA volunteers, Jane Carlton, Judith Padden, Sylvia Greenwood and Christine Parkinson. To visit: www.ysp.co.uk/naea BOOK TITLE AUTHOR Treasures of ancient America: the arts of pre-Columbian civilizations from Mexico to Peru S K Lothrop Neo-classical England Judy Marle Bronzes from the Deccan: Lalit Kala Nos. 3-4 Douglas Barrett Ancient Peruvian art [exhibition catalogue] Laing Art Gallery. Newcastle upon Tyne The art of the Canadian Eskimo W T Lamour & Jacques Brunet [trans] The American Indians : their archaeology and pre history Dean Snow Folk art of Asia, Australia, the Americas Helmuth Th. Bossert North America Wolfgang Haberland Sacred circles: two thousand years of north American Indian art [exhibition catalogue] Ralph T Coe People of the totem: the Indians of the Pacific North-West Norman Bencroft-Hunt Mexican art Justino Fernandez Mexican art Justino Fernandez Between continents/between seas: precolumbian art of Costa Rica Suzanne Abel-Vidor et al The art of ancient Mexico Franz Feuchtwanger Angkor: art and civilization Bernard Crosier The Maori: heirs of Tane David Lewis Cluniac art of the Romanesque period Joan Evans English romanesque art 1066-1200 [exhibition catalogue] Arts Council Oceanic art Alberto Cesace Ambesi 100 Master pieces: Mohammedan & oriental The Harvard outline and reading lists for Oriental Art. Rev.ed Benjamin Rowland Jr. Shock of recognition: landscape of English Romanticism, Dutch seventeenth-century school. American primitive Sandy Lesberg (ed) American Art: four exhibitions. -

Islamic Esotericism in the Bengali Bāul Songs of Lālan Fakir Keith Cantú [email protected]

Research Article Correspondences 7, no. 1 (2019): 109–165 Special Issue: Islamic Esotericism Islamic Esotericism in the Bengali Bāul Songs of Lālan Fakir Keith Cantú [email protected] Abstract This article makes use of the author’s field research as well as primary and secondary textual sour- ces to examine Islamic esoteric content, as mediated by local forms of Bengali Sufism, in Bāul Fa- kiri songs. I provide a general summary of Bāul Fakiri poets, including their relationship to Islam as well as their departure from Islamic orthodoxy, and present critical annotated translations of five songs attributed to the nineteenth-century Bengali poet Lālan Fakir (popularly known as “Lalon”). I also examine the relationship of Bāul Fakiri sexual rites (sādhanā) and principles of embodiment (dehatattva), framed in Islamic terminology, to extant scholarship on Haṭhayoga and Tantra. In the final part of the article I emphasize how the content of these songs demonstrates the importance of esotericism as a salient category in a Bāul Fakiri context and offer an argument for its explanatory power outside of domains that are perceived to be exclusively Western. Keywords: Sufism; Islam; Esotericism; Metaphysics; Traditionalism The history of the Bāul Fakirs includes centuries of religious innovation in which various poets have gradually created a folk tradition highly unique to Bengal, that is, Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. While there have been several important works published on Bāul Fakirs in recent years,1 in this ar- ticle I aim to contribute specifically to scholarship on Islamic esoteric con- tent in Bāul Fakiri songs, as mediated by local forms of Sufism.2 Analyses in 1. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

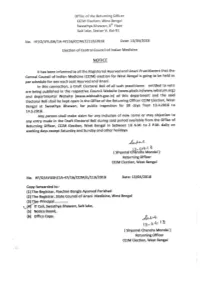

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

CCIM-11B.Pdf

Sl No REGISTRATION NOS. NAME FATHER / HUSBAND'S NAME & DATE 1 06726 Dr. Netai Chandra Sen Late Dharanindra Nath Sen Dated -06/01/1962 2 07544 Dr. Chitta Ranjan Roy Late Sahadeb Roy Dated - 01-06-1962 3 07549 Dr. Amarendra Nath Pal late Panchanan Pal Dated - 01-06-1962 4 07881 Dr. Suraksha Kohli Shri Krishan Gopal Kohli Dated - 30 /05/1962 5 08366 Satyanarayan Sharma Late Gajanand Sharma Dated - 06-09-1964 6 08448 Abdul Jabbar Mondal Late Md. Osman Goni Mondal Dated - 16-09-1964 7 08575 Dr. Sudhir Chandra Khila Late Bhuson Chandra Khila Dated - 30-11-1964 8 08577 Dr. Gopal Chandra Sen Gupta Late Probodh Chandra Sen Gupta Dated - 12-01-1965 9 08584 Dr. Subir Kishore Gupta Late Upendra Kishore Gupta Dated - 25-02-1965 10 08591 Dr. Hemanta Kumar Bera Late Suren Bera Dated - 12-03-1965 11 08768 Monoj Kumar Panda Late Harish Chandra Panda Dated - 10/08/1965 12 08775 Jiban Krishna Bora Late Sukhamoya Bora Dated - 18-08-1965 13 08910 Dr. Surendra Nath Sahoo Late Parameswer Sahoo Dated - 05-07-1966 14 08926 Dr. Pijush Kanti Ray Late Subal Chandra Ray Dated - 15-07-1966 15 09111 Dr. Pratip Kumar Debnath Late Kaviraj Labanya Gopal Dated - 27/12/1966 Debnath 16 09432 Nani Gopal Mazumder Late Ramnath Mazumder Dated - 29-09-1967 17 09612 Sreekanta Charan Bhunia Late Atul Chandra Bhunia Dated - 16/11/1967 18 09708 Monoranjan Chakraborty Late Satish Chakraborty Dated - 16-12-1967 19 09936 Dr. Tulsi Charan Sengupta Phani Bhusan Sengupta Dated - 23-12-1968 20 09960 Dr. -

Understanding the Contribution of Satya Shodhaak Samaj and Neo- Buddhism for Social Awakening

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 8, Issue 6, Jun 2020, 53–60 © Impact Journals UNDERSTANDING THE CONTRIBUTION OF SATYA SHODHAAK SAMAJ AND NEO- BUDDHISM FOR SOCIAL AWAKENING Prashant V. Ransure & Pankajkumar Shankar Premsagar Assistant Professor, Department of History, Maratha Vidya Prasarak Samaj's Arts Science and Commerce College Ozar MIG, Maharashtra, India Associate Professor, Department of History, Smt. G. G. Khadse College, Muktainagar, India Received: 10 Jun 2020 Accepted: 16 Jun 2020 Published: 27 Jun 2020 ABSTRACT Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have, diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups. Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups.1 The social reform movements, tried for the emancipation of these low caste people, before coming of these social reformers, many of the low caste people had chosen to come out from the caste system is by getting religious conversion, getting converted either to Christianity or to Islam, prior to these social reformers the saints like Kabir, Ravidas, Namdev, like wise and many other fought for the abolition of the caste system and emancipate the low caste from the social bondages.2 The other way for the untouchables was to get converted to either Islam or to Christianity, this was to get rid of the bondages of the humiliations of the caste system, but the conversion was not confined to the weaker sections, but in the medieval period too many people got converted to Islam or Christianity either by force or by their will. -

The Body, Subjectivity, and Sociality

THE BODY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIALITY: Fakir Lalon Shah and His Followers in Contemporary Bangladesh by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder B.S.S in Sociology, University of Dhaka, 2002 M.A. in Sociology, University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder It was defended on April 26, 2017 and approved by Lisa D Brush, PhD, Professor, Sociology Joseph S Alter, PhD, Professor, Anthropology Waverly Duck, PhD, Associate Professor, Sociology Mark W D Paterson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Sociology Dissertation Advisor: Mohammed A Bamyeh, PhD, Professor, Sociology ii Copyright © by Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder 2017 iii THE BODY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIALITY: FAKIR LALON SHAH AND HIS FOLLOWERS IN CONTEMPORARY BANGLADESH Mohammad Golam Nabi Mozumder, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 I introduce the unorthodox conceptualization of the body maintained by the followers of Fakir Lalon Shah (1774-1890) in contemporary Bangladesh. This study is an exploratory attempt to put the wisdom of the Fakirs in conversation with established social theorists of the body, arguing that the Aristotelian conceptualization of habitus is more useful than Bourdieu’s in explaining the power of bodily practices of the initiates. My ethnographic research with the prominent Fakirs—participant observation, in-depth interview, and textual analysis of Lalon’s songs—shows how the body can be educated not only to defy, resist, or transgress dominant socio-political norms, but also to cultivate an alternative subjectivity and sociality. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

An Assessment of Jotirao Phule's Approach to Hindu Social Reform

CONFRONTING CASTE AND BRAHMANISM: AN ASSESSMENT OF JOTIRAO PHULE’S APPROACH TO HINDU SOCIAL REFORM S.K. Chahal Abstract This paper examines the approach of Jotirao Govindrao Phule (1827- 1890), the foremost social reformer and thinker as well as one of the nation-builders of modern India, with regard to the issue of Hindu social reform in India. A radical social reformer of 19th-century Maharashtra, Phule visualized Hindu society free from all social inequalities based on caste, class and gender. He showed extreme concern for the suppressed and the marginalized sections of Hindu society, and started a crusade against the orthodoxy and the “slavery” it imposed upon the downtrodden sections of Hindu community for centuries. The paper is based on the proposition that Phule’s framework of Hindu social reform was radical and his movement was a sort of Hindu reformation movement. His approach to Hindu social reform appears to be altogether different from that of the “revivalist” reformers of 19th century who represented the so-called mainstream tradition of Hindu social reform in modern India. Phule came out with his own idea of the religion, i.e. Sarvajanik Satya Dharma (Universal Religion of Truth). In order to materialize his concept of “true religion”, he and his colleagues founded in 1873 Satyashodhak Samaj (society of truth seekers) in Pune. The set of principles the Samaj drew up shortly after its formation included belief in equality of all human beings, restoration of whose natural/human rights was one of its aims. Phule was more of a social revolutionary than a social reformer. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

District Handbook Murshidabad

CENSUS 1951 W.EST BENGAL DISTRICT HANDBOOKS MURSHIDABAD A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service, Superintendent ot Census OPerations and Joint Development Commissioner, West Bengal ~ted by S. N. Guha Ray, at Sree Saraswaty Press Ltd., 32, Upper Circular Road, Calcutta-9 1953 Price-Indian, Rs. 30; English, £2 6s. 6<1. THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS The Census Publications for West Bengal, Sikkim and tribes by Sudhansu Kumar Ray, an article by and Chandernagore will consist of the following Professor Kshitishprasad Chattopadhyay, an article volumes. All volumes will be of uniform size, demy on Dbarmapuja by Sri Asutosh Bhattacharyya. quarto 8i" x II!,' :- Appendices of Selections from old authorities like Sherring, Dalton,' Risley, Gait and O'Malley. An Part lA-General Report by A. Mitra, containing the Introduction. 410 pages and eighteen plates. first five chapters of the Report in addition to a Preface, an Introduction, and a bibliography. An Account of Land Management in West Bengal, 609 pages. 1872-1952, by A. Mitra, contajning extracts, ac counts and statistics over the SO-year period and Part IB-Vital Statistics, West Bengal, 1941-50 by agricultural statistics compiled at the Census of A. Mitra and P. G. Choudhury, containing a Pre 1951, with an Introduction. About 250 pages. face, 60 tables, and several appendices. 75 pages. Fairs and Festivals in West Bengal by A. Mitra, con Part IC-Gener.al Report by A. Mitra, containing the taining an account of fairs and festivals classified SubSidiary tables of 1951 and the sixth chapter of by villages, unions, thanas and districts. With a the Report and a note on a Fertility Inquiry con foreword and extracts from the laws on the regula ducted in 1950.