Overview of Land-Based Sources and Activities Affecting the Marine, Coastal and Associated Freshwater Environment in the West and Central African Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Oceans and Coasts, a Summary

The African Science-base for Coastal Adaptation: a continental approach. A report to the African Union Commission (AUC) at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (7-18 December 2009). Item Type Report Authors Abuodha, P. Publisher Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Download date 04/10/2021 02:16:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/9427 The African Science-Base for Coastal Adaptation: A Continental Approach A report to the African Union Commission (AUC) at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (7-18 December 2009) INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION OF UNESCO November 2009 Pamela Atieno Abuodha The African Science-Base for Coastal Adaptation: A Continental Approach Table of Contents Table of Contents ii List of Figures iv List of Tables vi Executive Summary vii Acknowledgements xvi PART I CLIMATE IMPACTS AND VULNERABILITIES IN 1 COASTAL LOW-LYING AREAS 1.1 Climate-change effects: the continental view 1 1.1.1 Overview of relevant work in IPCC AR4 2 1.1.2 Overview of more recent science 7 1.1.3 Consequences of climate change on the African coast 8 1.1.4 The most important effects and uncertainties in 12 Africa’s Climate-change adaptation Primary effects of Climate-change 13 1.1.4.1 Atmospheric and ocean temperature rise and acidification 13 1.1.4.2 Sea-level rise and coastal erosion 14 1.1.4.3 Precipitation and Floods 16 1.1.4.4 Drought and Desertification 18 1.1.4.5 Ocean-based hazards and change in currents 21 Compound issues affecting the coastal zone of Africa 24 1.1.4.6 -

Banjul Area, the Gambia Public Works & Landmarks Cape / Point

GreaterGreater BanjulBanjul AArea,rea, TheThe GGambiaambia GGreenreen MMapap Greater Banjul Area, The Gambia Public Works & Landmarks Cape / Point 13 12 16 Atlantic Road7 Atlantic BAKAUBAKAU AtlAtlanticntic 28 Old Cape Road Ocean 27 New Town Road Ocecean Kotu Independence Strand 1 Stadium 14 25 Cape Road CapeCape FAJARAFAJARA 4 Kotu 9 C 5 32 Point 20 r eeke e k 18 Jimpex Road KotuKotu KANIFINGKANIFING Badala Park Way 3 15 Kololi KOTUKOTU 2 Point Kololi Road LATRILATRI Pipeline Road Sukuta Road 21 KUNDAKUNDA OLDOLD 26 22 MANJAIMANJAI JESHWANGJESHWANG KUNDAKUNDA 6 17 19 31 DIPPADIPPA KOLOLIKOLOLI Mosque Road KUNDAKUNDA 11 NEWNEW JESHWANGJESHWANG StS t SERRESERRE r 24 eame a KUNDAKUNDA 10 m 15 30 29 EBOEEBOE TOWNTOWN 0 500 m 23 8 BAKOTEHBAKOTEH PUBLIC WORKS & LANDMARKS 10. SOS Hospital School 11. Westfield Clinic 21. Apple Tree Primary School Cemetery 22. Apple Tree Secondary School 1. Fajara War Cemetery Library 23. Bakoteh School 2. Old Jeshwang Cemetery 12. Library Study Center 24. Charles Jaw Upper Basic School 25. Gambia Methodist Academy Energy Infrastructure Military Site 26. Latri Kunda (Upper Basic) School 3. Kotu Power Station 13. Army Baracks 27. Marina International High School Government Office Place of Worship 28. Marina International Junior School 4. American Embassy 14. Anglican Church 29. Serre Kunda Primary School 5. Senegalese Embassy 15. Bakoteh East Mosque 30. SOS Primary and Secondary School 16. Catholic Church 31. St. Therese Junior Secondary School Hospital 17 . Mosque 32. University of the Gambia 6. Lamtoro Medical Clinic 18. Pipeline Mosque 7. Medical Research Council 19. St. Therese’s Church Waste Water Treatment Plant 8. -

World Bank Document

A. GLOBAL 'REPRESENTATIVEE'SYSTE.M. OFE MARI-NE-- .PROTECTED AREAS:*- Public Disclosure Authorized Wider14Carbbean, West-Afnca and SdtWh Atl :.. : ' - - 1: Volume2 Public Disclosure Authorized , ... .. _ _ . .3 ~~~~~~~~~~-------- .. _. Public Disclosure Authorized -I-~~~~~~~~~~y Public Disclosure Authorized t ;c , ~- - ----..- ---- --- - -- -------------- - ------- ;-fst-~~~~~~~~~- - .s ~h ort-Bn -¢q- .--; i ,Z<, -, ; - |rl~E <;{_ *,r,.,- S , T x r' K~~~~Grea-f Barrier Re6f#Abkr-jnse Park Aut lority ~Z~Q~ -. u - ~~ ~~T; te World Conscrvltidt Union (IUtN);- s A Global Representative System of Marine Protected Areas Principal Editors Graeme Kelleher, Chris Bleakley, and Sue Wells Volume II The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority The World Bank The World Conservation Union (IUCN) The Intemational Bank for Reconstruction and DevelopmentTIhE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. Manufactured in the United States of America First printing May 1995 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. This publication was printed with the generous financial support of the Government of The Netherlands. Copies of this publication may be requested by writing to: Environment Department The World Bank Room S 5-143 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. WORLD CNPPA MARINE REGIONS 0 CNPPAMARINE REGION NUMBERS - CNPPAMARINE REGION BOUNDARIES ~~~~~~0 < ) Arc~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~tic <_~ NorthoflEs Wes\ 2<< /Northr East g NorhWest / ~~~Pacific {, <AtlanticAtaicPc / \ %, < ^ e\ /: J ~~~~~~~~~~Med iter=nean South Pacific \ J ''West )( - SouthEas \ Pacific 1 5tt.V 1r I=1~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~LI A \ N J 0 1 ^-- u / Atrain@ /~ALmt- \\ \ (\ g - ASttasthv h . -

The History of Banjul, the Gambia, 1816 -1965

HEART OF BANJUL: THE HISTORY OF BANJUL, THE GAMBIA, 1816 -1965 By Matthew James Park A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History- Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT HEART OF BANJUL: THE HISTORY OF BANJUL, THE GAMBIA, 1816-1965 By Matthew James Park This dissertation is a history of Banjul (formerly Bathurst), the capital city of The Gambia during the period of colonial rule. It is the first dissertation-length history of the city. “Heart of Banjul” engages with the history of Banjul (formerly Bathurst); the capital city of The Gambia. Based on a close reading of archival and primary sources, including government reports and correspondences, missionary letters, journals, and published accounts, travelers accounts, and autobiographical materials, the dissertation attempts to reconstruct the city and understand how various parts of the city came together out of necessity (though never harmoniously). In the spaces where different kinds of people, shifting power structures, and nonhuman actors came together something which could be called a city emerged. Chapter 1, “Intestines of the State,” covers most of the 19 th century and traces how the proto-colonial state and its interlocutors gradually erected administration over The Gambia. Rather than a teleology of colonial takeover, the chapter presents the creation of the colonial state as a series of stops and starts experienced as conflicts between the Bathurst administration and a number of challengers to its sovereignty including Gambian warrior kings, marabouts, criminals, French authorities, the British administration in Sierra Leone, missionaries, merchants, and disease. Chapter 2, “The Circulatory System,” engages with conflicts between the state, merchants, Gambian kings, and urban dwellers. -

Inhalt Landeskunde Senegal Und Gambia

Inhalt Vorwort 9 Landeskunde Senegal und Gambia 11-76 Die Natur des Senegal 12 Geografie 12 Flora und Fauna 16 Landschafts- und Klimazonen .... 14 Nationalparks 21 Geschichte Senegals 22 Die westafrikan. Großreiche 22 Einbruch der Europäer 25 Die Königreiche der Wolof 24 Invasion und Kolonisation 27 Die Fulbe-Staaten 24 Der Weg in die Unabhängigkeit 29 Politik und Wirtschaft im Senegal 30 Jüngste Entwicklungen 30 Industrie 34 Wirtschaft 31 Tourismus 35 Die Menschen und ihre Religion 36 Bevölkerungsentwicklung 36 Religion 39 Ethnische Gruppen 37 Animistische Stammesreligionen 39 Sprache und Bildung 38 Islam & Christentum 40 Kunst und Kultur im Senegal 43 Bau- und Wohnformen 43 Film 52 Kunsthandwerk 45 Musik 53 Literaturgeschichte 46 Griots der Popmusik 53 Die Natur Gambias 58 Klimatabelle für Banjul 60 Gambia wird britische Kolonie .. 62 Geschichte Gambias 61 Autonomie und Unabhängigkeit 62 Portugiesen, Engländer und Franzosen am Gambia 61 Politik und Wirtschaft Gambias 64 Demokratie auf dem Prüfstand .. 64 Landwirtschaft 66 Jüngste polit. Entwicklungen 65 Industrie 67 Wirtschaft 66 Tourismus 68 Die Menschen und ihre Kultur 69 Bevölkerungsdaten 69 Musik 73 Ethnische Gruppen 69 Die Musikerkaste der Jali 73 Religion 70 Instrumente 74 Sprache 71 Musik im Wandel 74 Bildung 71 Literaturgeschichte 76 5 http://d-nb.info/920006353 Reisevorbereitung & Anreise 77-100 Reisevorbereitung Senegal 78 Reisedauer & Reisezeit 78 Sicherheit 81 Geld und Papiere 79 Ein-und Ausreiseformalitäten ... 81 Reisekosten 79 Infos für Behinderte 82 Zahlungsmittel 80 -

Overview of Land-Based Sources and Activities Affecting the Marine, Coastal and Associated Freshwater Environment in the West and Central African Region

Overview of Land-based Sources and Activities Affecting the Marine, Coastal and Associated Freshwater Environment in the West and Central African Region Item Type Report Citation UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 171. 110 pp. Publisher UNEP Download date 28/09/2021 10:14:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/312 Overview of Land-based Sources and Activities Affecting the Marine, Coastal and Associated Freshwater Environment in the West and Central African Region UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 171 UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME 1999 Note: The preparation of this Report was commissioned by UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme from Prof. E.S. Diop, (currently Senior Programme Officer, Division of Environmental Information, Assessment & Early Warning) under Project FP/1100-96-01. Design and layout by Mwangi Theuri, UNEP. The designations employed and the presentation of the materials in this document do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. The document contains the views expressed by the author(s) acting in their individual capacity and may not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP. 1999 United Nations Environment Programme The Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities GPA Co-ordination Office P.O. Box 16227 2500 BE The Hague Visiting address: Anna Paulownastraat 1, The Hague, The Netherlands West and Central Africa Action Plan Regional Co-ordinating Unit c/o Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Forêt 20 BP 650, Abidjan 20 Côte d’Ivoire This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational and non- profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. -

Jugendtypische Sprechweisen in Serekunda, Gambia Wirklichkeitsdeutungen Einer Subjektiven Lebenswelt

Jugendtypische Sprechweisen in Serekunda, Gambia Wirklichkeitsdeutungen einer subjektiven Lebenswelt Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde der Doktorin der Philosophie des Fachbereichs Asien-Afrika-Wissenschaften der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Schirin Agha-Mohamad-Beigui aus Hamburg Hamburg 2014 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof Dr. Roland Kießling Datum der Disputation: 30.07.2012 Tag des Vollzugs der Promotion: 05.12.2012 Schirin A.-M.-Beigui, »Jugendtypische Sprechweisen in Serekunda, Gambia. Wirklichkeitsdeutungen einer subjektiven Lebenswelt« © 2014 der vorliegenden Ausgabe: Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat OHG Münster. www.mv-wissenschaft.com © 2014 Schirin A.-M.-Beigui Alle Rechte vorbehalten Satz: Schirin A.-M.-Beigui Druck und Einband: MV-Verlag ISBN 978-3-95645-202-4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Verzeichnis der Gesprächstranskripte und Wortlisten 5 Danksagung 7 Abkürzungsverzeichnis 8 Konvention 9 Mandinka Sprache 15 1. Einleitung 17 1.1. Hintergrund und Ziele der Arbeit 17 1.2. Bisherige Untersuchungen zu Jugendsprachen 21 1.3. Analyserahmen 26 1.3.1. Bedeutungsfunktionen von Konzepten des Sonderwortschatzes 26 1.3.2. Verhandlung und Verortung sozialer Perspektiven in Interaktionen 28 1.3.3. Untersuchung der linguistischen Merkmale von Gesprächsaufnahmen und des Sprachwissens von Jugendlichen über boys’ talk / ghetto talk 31 1.4. Analysemethoden 32 1.4.1. Untersuchung der Konzepte des Sonderwortschatzes 32 1.4.2. Untersuchung der Sprechpraxis in Gesprächsaufnahmen 33 1.4.3. Einschränkungen an die Arbeit und Grenzen der Analyse 34 1.5. Datenerhebungsmethoden und Informantenmerkmale 37 1.5.1. Überblick über angewandte Erhebungsmethoden 37 1.5.2. Interviews, teilnehmende Beobachtungen und Informantenmerkmale 37 1.5.3. An der Datenerhebung mitwirkende Informanten B. und P. 38 1.5.4. -

Atelier Sur Les Systèmes Fonciers Et La Desertification

IDRC CRDI AAV GILD 70r C A N A D A . CMA o v o' V"y 3 A (Ic ARCHIV 103536 10 ) (0 wI)RC - Ub' Atelier sur le foncier et la d6sertification 7 au 9 Mars 1994, Dakar - SENEGAL Liste des Participants Nom/Institution Ali Abaab CIHEAM-IAM Montpellier BP 5056 34033 Montpellier. Francd Tel :(33) 67046000 Fax : (33) 67542527 Boubakar Moussa Ba Comite Inter-Etats de Lutte contre la Secheresse au Sahel CILSS BP 7110 Ouagadougou. Burkina Faso Tel : (226) 31 26 40 Fax (226) 31 08 68 Mamadou Ba CRDI BP 11007 CD Annexe Dakar. S6n6gal Tel :(221)24 42 31 Fax :(221)25 35 55 Andr6 Bathiono ICRISAT BP 12404 - Niamey Tel : (227) 72 25 29 Fax :(227) 73 43 29 .Abdoulaye Bathily Ministre de 11environnement et de la Protection de la Nature Building Administratif 4° etage Dakar Senegal Jacques Bilodeau Ambassadeur du Canada 45, Bd de la Republique Dakar Senegal Tel (221) 23 92 90 Fax (221) 23 54 90 Mohamed Boualga Organisation africaine de cartographie et t616d6tection 40, Bd Mohamed V Alger, Alg6rie Tel (213-2) 61 29 64 Fax (213-2) 77 79 38 G6rald Bourrier Directeur Regional/CRDI BP 11007 CD Annexe Dakar, S6n6gal Tel (221) 24 09 20 Fax (221) 25 32 55 Alioune Camara CRDI Dakar BP 11007 CD Annexe Dakar, S6n6gal Tel (221) 24 09 20 Fax (221) 25 32 55 Madeleine Ciss6 Comite National du CILSS Rue Parchappe x Huart Dakar, S6n6gal Tel : (221) 21 24 61 Mamadou Cissoko FONGS BP 269 - Thies S6n6gal Tel (221) 51 12 37 Fax (221) 51 20 59 Michael Cracknell ENDA Inter Arabe Cite Venus bloc 2 El Menzah VII 1004, Tunis Tunisie T&l : (216-1) 75 20 03/76 62 34 Mamadou Daff6 Organisation -

Historical Dictionary of the Gambia

HDGambiaOFFLITH.qxd 8/7/08 11:32 AM Page 1 AFRICA HISTORY HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF AFRICA, NO. 109 HUGHES & FOURTH EDITION PERFECT The Gambia achieved independence from Great Britain on 18 February 1965. Despite its small size and population, it was able to establish itself as a func- tioning parliamentary democracy, a status it retained for nearly 30 years. The Gambia thus avoided the common fate of other African countries, which soon fell under authoritarian single-party rule or experienced military coups. In addi- tion, its enviable political stability, together with modest economic success, enabled it to avoid remaining under British domination or being absorbed by its larger French-speaking neighbor, Senegal. It was also able to defeat an attempted coup d’état in July 1981, but, ironically, when other African states were returning to democratic government, Gambian democracy finally suc- Historical Dictionary of Dictionary Historical cumbed to a military coup on 22 July 1994. Since then, the democracy has not been restored, nor has the military successor government been able to meet the country’s economic and social needs. THE This fourth edition of Historical Dictionary of The Gambia—through its chronology, introductory essay, appendixes, map, bibliography, and hundreds FOURTH EDITION FOURTH of cross-referenced dictionary entries on important people, places, events, institutions, and significant political, economic, social, and cultural aspects— GAMBIA provides an important reference on this burgeoning African country. ARNOLD HUGHES is professor emeritus of African politics and former direc- tor of the Centre of West African Studies at the University of Birmingham, England. He is a leading authority on the political history of The Gambia, vis- iting the country more than 20 times since 1972 and authoring several books and numerous articles on Gambian politics. -

Making and Managing Femaleness, Fertility and Motherhood Within An

Making and managing femaleness, fertility and motherhood within an urban Gambian area Heidi Skramstad Dissertation submitted for the degree of Dr.Polit. Department of Social Anthropology University of Bergen March 2008 ISBN 978-82-308-0600-5 Bergen, Norway 2008 Printed by Allkopi Tel: +47 55 54 49 40 For Marit Skramstad, Mama Jamba, Aji Rugie Jallow and all other great mothers Contents CONTENTS........................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: ................................................................................................................................ 7 GENERAL INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 11 Organisation of the thesis............................................................................................................................ 14 SUBJECT FORMATION, DISCOURSES, HEGEMONIES AND RESISTANCE................................................................. 15 Ideology, hegemony or dominant discourses............................................................................................... 17 The discursive production of sex, gender, sexuality and fertility................................................................. 19 Women’s positions, mutedness and resistance ............................................................................................ 20 THE DISCURSIVE PRODUCTION -

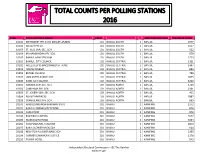

Total Counts Per Polling Stations 2016

TOTAL COUNTS PER POLLING STATIONS 2016 Code Name of Polling Station Count Administrative Area Registered voters 10101 METHODIST PRI. SCH.( WESLEY ANNEX) 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1577 10102 WESLEY PRI.CH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1557 10103 ST. AUG. JNR. SEC. SCH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 522 10104 MUHAMMADAN PRI. SCH. 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 879 10105 BANJUL MINI STADIUM 101 BANJUL SOUTH 1 BANJUL 1723 10201 BANJUL. CITY COUNCIL 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1151 10202 WELLESLEY & MACDONALD ST. JUNC. 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1497 10203 ODEON CINEMA 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 889 10204 BETHEL CHURCH 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 799 10205 LANCASTER ARABIC SCH. 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 1835 10206 22ND JULY SQUARE . 102 BANJUL CENTRAL 1 BANJUL 3200 10301 GAMBIA SEN. SEC. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 1730 10302 CAMPAMA PRI. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 2361 10303 ST. JOSEPH SEN. SEC. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 455 10304 POLICE BARRACKS 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 1887 10305 CRAB ISLAND JUN. SCH. 103 BANJUL NORTH 1 BANJUL 669 20101 WASULUNKUNDA BANTANG KOTO 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2272 20102 BAKAU COMMUNITY CENTRE 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 878 20103 CAPE POINT 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 878 20104 KACHIKALI CINEMA 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 1677 20105 MAMA KOTO ROAD 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 3064 20106 INDEPENDENCE STADIUM 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2854 20107 BAKAU LOWER BASIC SCH 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 614 20108 NEW TOWN LOWER BASIC SCH. 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2190 20109 FORMER GAMWORKS OFFICE 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 2178 20110 FAJARA HOTEL 201 BAKAU 2 KANIFING 543 Independent Electoral Commission – IEC The Gambia www.iec.gm 20201 EBO TOWN MOSQUE 202 JESHWANG 2 KANIFING 5056 20202 KANIFING ESTATE COMM. -

Liste Des Candidats Admis Centre : Stade : 1 1755199301256 ADIOYE JULIUS COLES 23/03/1993 DAKAR AGENT DE CONSTATATION ACD006623

République du Sénégal Un Peuple Un But Une Foi Ministère de l'Economie des Finances et du Plan DIRECTION GENERALE DES DOUANES Division de la Formation Liste des candidats Admis Centre : Dakar Stade : Amadou Barry Guédiawaye N° CIN Nom Prénom Date Lieu Section Numéro naissance naissance inscription 1 1755199301256 ADIOYE JULIUS COLES 23/03/1993 DAKAR AGENT DE ACD006623 CONSTATATION 2 1126200400295 ADIOYE MINEL 12/10/1995 CAROUNATE AGENT DE ACD016848 CONSTATATION 3 1747200300506 ADJ CHEIKH 27/08/1995 BATAL CONTRÔLEUR COD026066 4 1755199501769 AGBO DESIRE AMATH 15/08/1995 DAKAR PRÉPOSÉ PRD005008 5 1756199601276 AGNE BABA 10/07/1996 DAKAR AGENT DE ACD023831 CONSTATATION 6 1619200809190 AIDARA AMADOU LO 04/04/1997 THIES AGENT DE ACD026605 CONSTATATION 7 1341199200306 AIDARA HAMET 06/05/1992 BAKEL AGENT DE ACD015752 CONSTATATION 8 1344198900117 AIDARA MAHAMADOU 09/12/1989 GOUMBAYEL AGENT DE ACD009885 CONSTATATION 9 1684201300118 AIDARA SECK 13/06/1994 GOUYE DIAMA PRÉPOSÉ PRD016377 10 1619199402914 AIDARA SIDY YAKHYA 24/03/1994 THIES CONTRÔLEUR COD019873 11 1070199500198 AIME GILLES GASTON 20/01/1995 ZIGUINCHOR CONTRÔLEUR COD019022 12 1765201001983 AKPAKA MOHAMED 23/11/1992 PIKINE AGENT DE ACD021936 CONSTATATION 13 1751199201998 ALAVO DANIEL 30/05/1992 DAKAR AGENT DE ACD018114 MOUSTAPHA CONSTATATION 14 1910201001825 AMAR MASSAER 21/02/1988 GUÉDIAWAYE PRÉPOSÉ PRD030894 15 1910201200930 ANE AMADOU 17/11/1993 GUEDIAWAYE AGENT DE ACD016427 CONSTATATION 16 1762199200481 ANE EL HADJI MALICK 23/04/1992 PARCELLES AGENT DE ACD016565 ASSASSINES CONSTATATION