An Appeal from New to Old Austrians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Long-Lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on Its Spatial Equilibrium

IZA DP No. 10095 The Long-lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on its Spatial Equilibrium Christoph Eder Martin Halla July 2016 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Long-lasting Shadow of the Allied Occupation of Austria on its Spatial Equilibrium Christoph Eder University of Innsbruck Martin Halla University of Innsbruck and IZA Discussion Paper No. 10095 July 2016 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. -

Austrians Are Most Concerned About Health and Long-Term Care

O E C D Risks That Matter Survey 2020 AUSTRIA July 2021 www.oecd.org/social/risks-that-matter.htm Austrians are most concerned about health and long-term care The OECD’s cross-national Risks that Matter Yet almost 60% of Austrians also say they Fig. 2. Share of respondents identifying survey examines people’s perceptions of worry about LTC for themselves. personal networks as their primary source of support in case of financial difficulty social and economic risks and how well they Like respondents in most other countries, feel their government reacts to their concerns. Austrians are more likely to count on friends % The survey polled a representative sample of and family than on government to support 70 25000 people aged 18 to 64 years old in 25 them through financial difficult (Fig. 2). And 60 OECD countries to understand better what over 60% of Austrians say that government 50 citizens want and need from social policy – should be doing more or much more to 40 particularly in the face of the COVID-19 support their economic and social security, 30 pandemic. relative to a 68% average across the OECD. 20 Over 80% of respondents in Austria report that When evaluating specific social programmes, 10 their country’s economic situation worsened a slim majority of Austrians agree or strongly 0 during the pandemic, compared to a cross- AUT OECD DNK SVN agree with having good access to healthcare national average of 71% (Fig. 1). This – a noteworthy outcome considering the economic sentiment is also reflected in the health exigencies of the pandemic and the Fig. -

Exile and Holocaust Literature in German and Austrian Post-War Culture

Religions 2012, 3, 424–440; doi:10.3390/rel3020424 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Haunted Encounters: Exile and Holocaust Literature in German and Austrian Post-war Culture Birgit Lang School of Languages and Linguistics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville 3010 VIC, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 2 May 2012; in revised form: 11 May 2012 / Accepted: 12 May 2012 / Published: 14 May 2012 Abstract: In an essay titled ‗The Exiled Tongue‘ (2002), Nobel Prize winner Imre Kertész develops a genealogy of Holocaust and émigré writing, in which the German language plays an important, albeit contradictory, role. While the German language signified intellectual independence and freedom of self-definition (against one‘s roots) for Kertész before the Holocaust, he notes (based on his engagement with fellow writer Jean Améry) that writing in German created severe difficulties in the post-war era. Using the examples of Hilde Spiel and Friedrich Torberg, this article explores this notion and asks how the loss of language experienced by Holocaust survivors impacted on these two Austrian-Jewish writers. The article argues that, while the works of Spiel and Torberg are haunted by the Shoah, the two writers do not write in the post-Auschwitz language that Kertész delineates in his essays, but are instead shaped by the exile experience of both writers. At the same time though, Kertész‘ concept seems to be haunted by exile, as his reception of Jean Améry‘s works, which form the basis of his linguistic genealogies, shows an inability to integrate the experience of exile. -

Religious Determinants of Demographic Events

VIENNA INSTITUTE OF DEMOGRAPHY Working Papers 01 / 2006 Anne Goujon, Vegard Skirbekk, Katrin Fliegenschnee, Pawel Strzelecki New Times, Old Beliefs: Projecting the Future Size of Religions in Austria Vienna Institute of Demography Austrian Academy of Sciences Prinz Eugen-Straße 8-10 · A-1040 Vienna · Austria E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.oeaw.ac.at/vid Abstract Projecting the religious composition of the population is relevant for several reasons. It is a key characteristic influencing several aspects of individual behaviour, including marriage and childbearing patterns. The religious composition is also a driver of social cohesion and increased religious diversity could imply a more fragmented society. In this context, Austria finds itself in a period of transition where the long-time dominant Roman-Catholic church faces a serious decline in membership, while other groups, particularly the seculars and the Muslims, increase their influence. We project religions in Austria until 2051 by considering relative fertility rates, religion-specific net migration, and the rate of conversion between religions and transmission of religious beliefs from parents to children. We find that the proportion of Roman Catholics is likely to decrease from 75% in 2001 to less than 50% by the middle of the century, unless current trends in fertility, secularisation or immigration are to change. The share of Protestants is estimated to reach a level between 3 and 5% in 2051. The most uncertain projections are for those without religious affiliation: they could number as little as 10% and as many as 33%. The Muslim population—which grew from 1% in 1981 to 4% in 2001—will, according to our estimates, represent 14 to 26% of the population by 2051. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

From Habsburg to Hitler to Haider: the Peculiarities of Austrian History Harry Ritter Western Washington University, [email protected]

Western Washington University Masthead Logo Western CEDAR History Faculty and Staff ubP lications History 5-1999 From Habsburg to Hitler to Haider: The Peculiarities of Austrian History Harry Ritter Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/history_facpubs Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ritter, Harry, "From Habsburg to Hitler to Haider: The eP culiarities of Austrian History" (1999). History Faculty and Staff Publications. 38. https://cedar.wwu.edu/history_facpubs/38 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. German Studies Association From Habsburg to Hitler to Haider: The Peculiarities of Austrian History Author(s): Harry Ritter Source: German Studies Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (May, 1999), pp. 269-284 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the German Studies Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1432076 . Accessed: 29/10/2014 16:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Austria and Its Culture Facts & Figures

Austria and its Culture Facts & Figures History of Austria Government Today’s Republic of Austria is a small state, whose Country Name: conventional long form: origins can be traced back into history. Populated since Republic of Austria, conventional short form: the prehistoric times, Austria’s location in the heart of Austria, local short form: Oesterreich, local long Europe means that it has had its share of the continent’s form: Republik Oesterreich historical developments. It evolved from a border region Government Type: Federal Republic into a powerful empire and multiracial state, which Capital: Vienna collapsed at the end of the First World War. In 1918, the Administrative Divisions: 9 states, small, newly proclaimed Republic of Austria had at first (Bundesland, Burgenland, Kaernten, to come to terms with the European environment. Austria Niedersoesterreich, Oberoesterreich, Salzburg, emerged from the Second World War and the sufferings Steiermark, Tirol, Vorarlberg, Wien associated with it as a state that feels secure in its Independence: 1156 (from Bavaria existence and which plays a decisive role in Europe. Legal System: Civil law system with Roman law origin; judicial review of legislative acts by Geography the Constitutional Court; separate administrative Location: Central Europe, north of Italy and Slovenia Area: Total= 83,858 sq km, Water= 1,120 sq km, Land= 82,738 sq and civil/penal supreme courts; accepts km compulsory neutrality Climate: Temperate; continental; cloudy; cold winters with frequent rain in lowlands & snow in the mountains; cool summers with Economy occasional showers GDP: purchasing power parity - $227.7 billion Terrain: In the west & south mostly mountains (Alps); along the GDP per Capita: purchasing power parity - $27,900 eastern & northern margins mostly flat or gently sloping. -

The Anschluss Movement and British Policy

THE ANSCHLUSS MOVEMENT AND BRITISH POLICY: MAY 1937 - MARCH 1938 by Elizabeth A. Tarte, A.B. A 'l11esis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Part ial Fulfillment of the Re quirements f or the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin May, 1967 i1 PREFACE For many centuri.es Austria. bad been closely eom'lect E!d \'lieh the German states. 111 language and eulture. Austri.a and Germany had always looked to each other. AS late as the t~tentieth century. Austria .st111 clung to her traditional leadership in Germany . In the perlod following the First World War, Austria continued to lo(!)k to Germany for leadership. Aus tria, beset by numerous economic and social problems. made many pleas for uni on with her German neighbor. From 1919 to 1933 all ;novas on the part of Austria and Germany for union, -v.71\ether political oreeon01;n1c. were th"larted by the signatories of the pea.ce treaties. Wl ,th the entrance of Adolf Hitler onto the European political stage, the movement fQr the Anschluss .. - the union of Germany and Austria .- t ook on a different light. Austrians no longer sought \.Ulion with a Germany v.ilich was dominated by Hitler. The net"l National $Gclalist Gertna,n Reich aimed at: the early acq'U1Si ,tiQn of Austria. The latter "(vas i mportant to the lteich fGr its agricultural and Batural reSources and would i mprove its geopolitical and military position in Europe. In 1934 the National Soci aU.sts assaSSinated Dr .. U.:. £tlto1bot''t Pollfuas, the Aust~i ..\n Cbaneellot'l in ,an 8.'ttcmp't to tillkltl c:ronet:Ql or his: eountry. -

Austrian and Hungarian Values and Norms in Cross-Cultural Management Research

n. 3 - 2015 Austrian and Hungarian values and norms in cross-cultural management research Anikó Tompos Summary and list of contents: 1. Introduction – 2. The concept of culture in cross- cultural management research – 3. Austria and Hungary in dimension-based investigations – 4. Austria and Hungary in cultural standards research – 5. Critical interactional incidents – 6. Implications for cross-cultural training – 7. Conclusion – References. Abstract Different historical perspectives allow for different conclusions about whether the Austrian and Hungarian cultures have much or little in common. This paper looks at the Austrian and Hungarian values and practices as characterised in the findings of cross-cultural management investigations. In doing so, it overviews and discusses the results of two research paradigms, the dimension-based approach and the cultural standards method. Austrian cultural standards are illustrated by critical interactional incidents recollected by Hungarian interviewees within the framework of an Austro-Hungarian research project. The paper concludes that although some of the findings are inconsistent between and even within the two research lines, the revealed values and behavioural patterns are useful for informal self-training as well as more formal intercultural trainings. Keywords : Cross-cultural management research, Cultural dimensions, Cultural standards, Critical interactional incidents, Cross-cultural training 1. Introduction The culture of Austria and that of Hungary are generally seen as quite similar or very different depending on the perspective one takes. Those concentrating on the long common past of the two countries ending in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy between 1867 and 1918 would generally assume that it is quite similar. At the same time, if we look at the origin and historical-societal roots of the two cultures, or Anikó Tompos Austrian and Hungarian values and norms in cross-cultural management research Impresa Progetto - Electronic Journal of Management, n. -

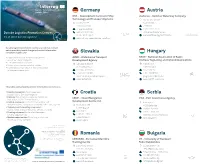

Germany Austria Slovakia Hungary Serbia Romania Bulgaria Croatia

Danube SKILLS Germany Austria DST - Development Centre for Ship viadonau - Austrian Waterway Company Technology and Transport Systems Donau-City-Straße 1 Oststrasse 77 1220 Vienna 47057 Duisburg Ulf Meinel Friederike Dahlke +43 50 4321-1625 Danube Logistics Promotion Centres +49 203 99 369 68 [email protected] [email protected] www.viadonau.org/en/economy It‘s all about Danube logistics! www.dst-org.de/en/danube-logistics/ Danube logistics promotion centres are national contact points providing free of charge and neutral information on Danube logistics for Slovakia Hungary • Cargo owners and other potential users of ARVD - Waterborne Transport RSOE - National Association of Radio inland waterway transport Development Agency Distress-Signalling and Infocommunications Port and terminal operators • Lamacská cesta 8 1 Elnök utca • Shipping companies and ship brokers • Forwarding companies with inland navigation 811 04 Bratislava 1089 Budapest in their service portfolio Veronika Mezeyová Gergely Mező + 421 907 799 891 +36 1 303 0168 [email protected] [email protected] www.arvd.gov.sk www.logisztika.rsoe.hu The public contact points provide information & services on • Danube navigation: Advantages and Croatia Serbia possibilities of Danube navigation • Fairway: Water levels, navigation conditions, CRUP - Inland Navigation PGA - Port Governance Agency lock status, traffic information etc. Development Centre Ltd. • Ports & Terminals: Contact data, handling and Nemanjina 4 storage facilities, companies operating in the Danube ports Nova cesta 180 11000 Belgrade Shipping and forwarding companies: • 10 000 Zagreb Vladimir Pavlovic Contact data, transported cargo, served countries Ivan Šuker • Funding schemes: National and European +381 11 6556 535 funding opportunities +38 5 91 4181 697 [email protected] • Market opportunities: Promising markets for [email protected] www.aul.gov.rs inland waterway transport www.crup.hr Danube SKILLS project www.interreg-danube.eu/danube-skills Imprint: CERONAV - Romanian Maritime Training Centre Str. -

“The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898" (2019)

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2019 “The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria- Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898 Evan Haley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Haley, Evan, "“The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898" (2019). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 58. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/58 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 “The Wickedest Man on Earth”: US Press Narratives of Austria-Hungary and the Shaping of American National Identity in 1898 The press is one of the cornerstones of American society. Their ability to record and influence the history of the United States has shown itself countless times throughout the country’s history, and although its power has moved through various mediums and time periods it remains a vital part of how Americans perceive themselves and the world around them. It is at once a mirror and a window; the problem is that this window is not always clear, and our mirror does not always show us the truth. The same was true in 1898. Newspapers were a vital source of information for almost all Americans. -

We Love Our Heimat, but We Need Foreigners” Tourism and the Reconstruction of Austria, 1945– 55

:H/RYH2XU+HLPDWEXW:H1HHG)RUHLJQHUV7RXULVPDQGWKH5HFRQVWUXFWLRQ RI$XVWULD² *XQGROI*UDPO -RXUQDORI$XVWULDQ6WXGLHV9ROXPH1XPEHU)DOOSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI1HEUDVND3UHVV '2,RDV )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by The University Of Texas at Austin, General Libraries (16 Aug 2016 23:44 GMT) “We Love Our Heimat, but We Need Foreigners” Tourism and the Reconstruction of Austria, 1945– 55 Gundolf Graml In the fall of 1945, President Karl Renner made what must have been a surpris- ing plea amidst the ruins of World War II: “Wir lieben unsere Heimat, aber wir brauchen die Fremde! Wir brauchen den Fremdenverkehr und laden alle Welt zu uns zu Gaste. Wien und Salzburg werden als Stätt en der Kunst, unsere Al- pen als touristische Ziele ersten Ranges die Fremden mit Freude begrüßen.”1 Renner’s statement features the very elements of economic self- colonization and tourist commodifi cationthat have formed a critical target throughout the postwar period for writers such as Ingeborg Bachmann, Franz Innerhofer, Th omas Bernhard, Felix Mitt erer, Norbert Gstrein, and Nobel Laureate Elfriede Jelinek, to name only a few. By addressing the rapid social, cultural, economic, and environmental transformations caused by the stun- ning growth of the tourism sector in Austria aft er 1945, these literary works have also contributed to the long overdue dismantling of Austria’s conserva- tive and patriarchal sociopolitical structures and have therefore become le- gitimate parts of the literary canon of post- 1945 Austria. However, over time, the literary tourism critique has affi rmed a notion of Austrian reality as hid- den, covered up, concealed, camoufl aged— the list could go on— by tourism.